![]()

Part I

Health and Development: Perspectives and Issues

![]()

1

Introduction: Health and Development

David R.Phillips and Yola Verhasselt

The health of populations and individuals is inextricably bound up with development. Development, in the most general meaning of the word, entails change and often important alterations to people’s living environments. However, many studies and projects related to development have ignored or skirted around the health dimension. This has been highlighted in recent years by a number of authors and has been brought into sharp focus by the World Health Organization’s publication in 1992 of a report of the WHO Commission on Health and Environment, entitled Our Planet, Our Health (WHO 1992a). This report takes a systematic view of global change and impacts on food supply, water, energy industry and settlements, and proposes certain strategies and actions. This current book provides very much a complementary perspective, discussing important underlying issues of health change with development and providing specific country and regional studies of health and development.

Health and Development

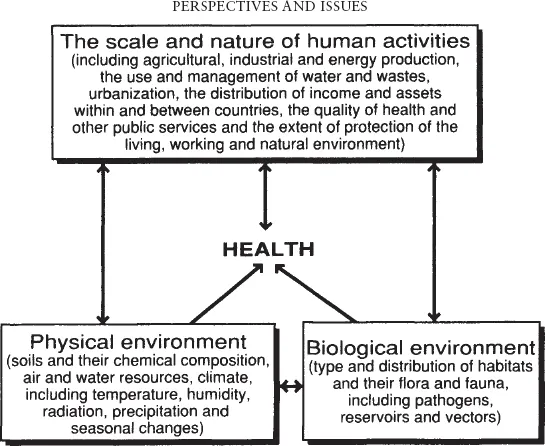

The two terms, beguilingly simple, defy concise and consistent definition. Health is much more than the absence of diagnosed physical disease, although the ‘medical model’ of medical school training has, often perforce, tended to stress this aspect of health. The constitution of the World Health Organization sees health as ‘a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’. It implies complex interactions between humans and their environments, more particularly between social and economic factors, physical environment and biological environment (Figure 1.1). The disease ecology school of medical geography, developed strongly under May’s influence, has recognized this complex, changing and delicate interrelationship for many years (Learmonth 1988).

Figure 1.1 Interaction between human activities and the physical and biological environment

Source: WHO (1992a)

Development, like health, is equally an elusive concept. Many economic definitions see development as being a phenomenon measurable by increasing per capita income or gross national product (GNP). While development does, undoubtedly, have a quantifiable fiscal element, it has many more subtle elements, to do with distribution of resources, access to opportunities (services, jobs, housing, education) and political/human rights. Seers (1969) sees development as of necessity increasing aspects of human dignity—which means access to basic needs: food, shelter, a job—and also political participation. Development is therefore generally understood as the process of improving the quality of all aspects of human life (WHO 1992a).

A complex interrelationship exists between health and development; it is certainly not a one-way relationship, and there are surely reciprocal and synergistic elements to it. It has long been acknowledged that the health status of the population in any particular place or country influences development. It can be a limiting factor, as generally poor individual health can lower work capacity and productivity; in aggregate in a population, this can severely restrict the growth of economies. On the other hand, economic development can make it possible to finance good environmental health, sanitation and public health campaigns—education, immunization, screening and health promotion—and to provide broader-based social care for needy groups. General social development, particularly education and literacy, has almost invariably been associated with improved health status via improved nutrition, hygiene and reproductive health. Socio-economic development, particularly if equitably spread through the population—although this is rarely the case— also enables housing and related services to improve. The classical cycle of poverty can be broken by development.

However, it is notoriously difficult to provide generalizations about the relationships between economic development and a population’s health status. We cite below examples in which correlations between GNP and life expectancy are not straightforward. There are many examples to show how economic development has contributed to improving quality of life and health status, via indicators such as increased life expectancy, falling infant, child and maternal mortality and enhanced access to services. By contrast, there are examples in which economic development, infrastructure expansion and agricultural intensification do not always coincide with improved human well-being. There is, in fact, growing realization that macroeconomic changes may not always filter down to benefit all of the population, and many perhaps soundly based policies in economic terms—notably structural adjustment policies—can have devastating human effects in increasing poverty and maldistribution of resources. In the face of these policies, the health sector alone cannot overcome concomitant health and welfare problems.

Recently, the WHO has recognized three major groups of problems which have contributed to a growing ‘health crisis’ in many countries, or which have hindered a clear improvement of health with development (Weil et al. 1990). It behoves the readers of this book to bear in mind these three major problems: first, the very magnitude and diversity of health hazards associated with development; secondly, the cost of diseases caused by industrialization and urbanization and also by medicine itself, the iatrogenic diseases; and, thirdly, the need for, or imposition of, macroeconomic adjustment which has resulted in major cuts in the health and social budgets of many developing— and some developed—countries.

The Impact of Development Policies on Health

It is important to recognize that many development policies designed to improve living standards and economic conditions of communities can have unexpected or unintended effects on health. These can be what Phillips (1990) calls the ‘health by-products’ of industrialization, which include risks from new dangers at work, exposure to toxic substances, effluent, radiation, traffic pollution and general industrial noise and waste in the environment. They can include side-effects of agricultural expansion projects which, at the macro-level, can help nations to feed themselves but which, locally, can bring workers and residents into contact with agricultural chemicals, fertilizers, pesticides and diseases such as malaria or schistosomiasis, whichcan be associated with unmonitored extension of irrigation. These by-products of development are often reflected in changing epidemiological profiles (the types of diseases from which people suffer). As we discuss below, many poor countries now face a double health burden, from continued prevalence of malnutrition, respiratory infections and diarrhoeal diseases, but also from vastly growing health problems usually associated with industrialization and urbanization: occupational hazards, accidents, cardio-vascular disease, cancers, substance abuse and increasing misuse of pharmaceuticals and quasi-modern cures.

It is therefore important that development projects, whether locally sponsored or supported by international donor agencies, include not only needs assessments but also assessments of environmental impact and health consequences. It is now recognized that, in some sectors, notably in the field of water resource development, engineers and planners have increasingly become aware of potential environmental and health consequences of schemes. A move towards genuine intersectoral co-operation, so often platitudinously stressed, has been possible. However, in many aspects of development policies, the health consequences have been ignored or underrated. This danger may yet increase in the 1990s, when less coordinated, individual and entrepreneurial schemes may be replacing larger-scale bilateral official projects which, in theory, have the scope for more considered assessment of impacts. Weil et al. (1990) suggest that the impacts on health of development policies need to be considered in at least five areas outside the health sector, all of which are closely associated with economic growth:

- Macroeconomic policies, especially adjustment policies, public expenditure, trade policies and household responses.

- Agricultural policies: irrigation systems; pesticide use; land policy and resettlement; agricultural research and nutrition.

- Industrial policies: industrial development policies (and location of industry); occupational health policies; control of water and air pollution; management of hazardous wastes.

- Energy policies: indoor air pollution, domestic fuel use; fuel scarcity and fuel gathering; fuel pricing and energy subsidies; control of pollution from industrial energy sources; health risks presented by hydroelectric power programmes.

- Housing policies: housing conditions and health; low-income housing policies, slum and squatter clearance; public provision of housing and infrastructure; sites-and-services programmes; upgrading programmes.

All of these five sectors clearly have a potential impact on the health of residents and workers. They are all closely interrelated in many instances, and readers of this book will see evidence in a number of chapters and case studies of their effects. Many have very direct impacts on the localenvironment and often have environmental change potential. It is to this important topic that we now turn.

Changing Environmental Conditions and Health

Environmental change can be of many types and scales. There can be direct change in the local living environment—new housing, factories, reservoirs— or change may be at a much more widespread level, including the impact on health of global environmental change. In addition, what might be called the socio-cultural environment—people’s social behaviour, nutritional preferences and consumption habits—is also very important. The understanding of the dynamics of environmental changes of many sorts is now quite good at a theoretical level, but the translation of theoretical knowledge into practical health improvements is not always easy. For example, at a global level, it is known how to reduce or at least contain global warming; but how can this, practically, be achieved? At the personal lifestyle level, in developed countries, there can hardly be an adult or teenager who does not know of the positive and strong correlation between, say, tobacco smoking and lung cancer; yet why do so many people continue to smoke? Individual lifestyle decisions build up into macro-consumer demand, with health consequences to the individual, and health by-product impacts on all. In addition, a mass of research on genetic predisposition to certain diseases is now becoming available, but the precise role of environmental factors as triggers or stimuli is not fully understood, although many associations have been suggested (Foster 1992).

Bentham, in Chapter 2 of this book, reviews the evidence for global environmental change and its potential for health impacts, some of which are already evident. The well-known depletion of the ozone layer and increased exposure to ultraviolet radiation are discussed, and a steady increase in skin cancers, particularly the highly dangerous form, melanoma, is explained. This may be particularly significant in the Southern hemisphere, and Australian health promotion efforts, for example, are now strongly geared to melanoma risk avoidance. Bentham also points to the obvious effects of global environmental change on health, many of which are only now becoming appreciated. A particular health hazard might be an extension north and south of the warm climatic zones in which what are currently regarded as mainly tropical diseases may in future flourish. This applies particularly to vector-borne diseases such as malaria, dengue, yellow, fever and trypanosomiasis. Indirect impacts of warmer climates include the potential for increased incidence of food poisoning. Bentham notes that, while there are numerous scare stories associated with macro-scale environmental change, there is no room for complacency. It may be that the exact health sequelae of environmental change may to an extent be speculative, but scientific evidence is growing, and it is certain that increasing serious attention needs to be devoted to this theme. There will surely be both health and economic consequences of environmental change which must be anticipated by us all.

Malaria provides a specific example of a disease that is eradicable but remains one of the most prevalent infectious conditions worldwide, although it principally still affects poorer tropical countries. According to WHO estimates, nearly half of the world population is at risk in more than 100 countries (with an estimated 110 million cases and 270 million people carrying the malaria parasites). It is a debilitating disease and, as such, an obstacle to economic development. It remains a major cause of death (with 1–1.5 million deaths annually), particularly among young children.

Malaria has been eradicated in some parts of the world, for example in Southern Europe. In other regions, however, it remains a major threat and has also seen a resurgence. There are various reasons, mostly concurrent. Among the main causes we can cite loss or reduction of vector control due to the success of previous eradication campaigns and/or to financial restrictions related to structural adjustment; growing resistance of the mosquito vector to insecticides and of the parasite to the cheap and common anti-malaria drugs; the expansion of irrigated land and the development of agricultural schemes increasing population mobility and rapid urban expansion. In the future, global climate change is also likely to increase the area of geographic distribution suitable for the anopheles mosquito. South Asia generally and Sri Lanka in particular witnessed major malarial eradication efforts with notable success after the Second World War. Consequently, in the Dry Zone, where malaria is endemic, agricultural development took place, attracting migrants from malaria-free zones. A major malaria resurgence followed. The role of migration was important, but also financial constraints with regard to vector control and difficulties of internal political disorder are elements in the explanation of the resurgence. In many other countries, malarial resurgence during the late 1980s has been related to a weakening of control programmes. Elsewhere, for example in Brazil and in Rwanda, new land has been brought into cultivation because of population pressure. New in-migrant agricultural workers have been exposed to settings with a high malarial risk. The incidence of the disease has often threatened the success and continuation of such agricultural extension policies.

Urbanization=Modernization=Better Health?

The question whether urbanization equates with modernization and better health is an important question in health and development, since many aspects of development theory have held the explicit or implicit assumption that development (in its very many definitions) and modernization will beassociated with urbanization. The modernization model, in particular, expected that virtually all economic growth would follow a Western industrial pattern (Hewitt 1992). While there have been valiant experiments to try alternative paths for development on a small scale, and especially for the rural areas in which most Third World residents live, many countries have settled on variants of industrialization strategies as their way forward (Todaro and Stilkind 1981; Kitching 1982; Simmonds 1988; Hewitt et al. 1992). These have almost inevitably entailed greater urbanization. The concentration of people which this entails and many of the industries themselves, by the nature of their activities, their environmental impacts and their effects on society and family life, have added to health hazards compared to more traditional rural and agricultural settlements and activities (Smith 1992).

It is important to differentiate modernization and industrialization. Modernization has historically been perceived as the process of change towards social, economi...