- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book offers an exciting new collection of recent research on the actual processes that humans use when making decisions in their everyday lives and in business situations. The contributors use cognitive psychological techniques to break down the constituent processes and set them in their social context. The contributors are from many different countries and draw upon a wide range of techniques, making this book a valuable resource to cognitive psychologists in applied settings, economists and managers.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

Fundamentals

Introduction to Part I

This book comprises a set of chapters which have been especially written for this volume and which offer a description and a critical evaluation of important research on the psychology of decision making. The chapters examine the nature of the psychological processes underlying decision making and the problems that people face in their everyday decisions. The authors’ approach is concerned with explaining how decisions are made in terms of motives, cognitive processes and mental representations. They draw on the insights of cognitive psychology to analyse the decision into more elementary processes. As such, this is a descriptive approach that can be contrasted with the normative and mathematical theories that have dominated much psychological and economic thinking in the study of decision making. The emphasis is on the analysis of what individuals actually do rather than on comparisons with idealised optimal or rational decision makers. The decision process is considered to be one that is extended in time: it involves a series of information search, judgement and evaluation processes which are followed by further post-decision processes that serve to help people to adjust to the implications of their decisions and to understand their own goals and values. It is recognised that decisions are made within a social context and need to be justified to oneself and to others. In a similar vein the question of helping people to improve their decisions is approached from considerations of how they actually make them, rather than from a narrow focus on discrepancies between actual and idealised decisions.

The chapters cover and summarise important decision research up to 1996. The intention is that the volume should serve as a source book for those who want to update their knowledge about research within the descriptive decision making approach. In addition, the book presents some of the most recent results of the authors’ own decision making research.

Part I consists of two chapters. The first, by Crozier and Ranyard, provides an introduction to the volume by identifying the themes and issues which characterise contemporary research on decision making from a cognitive perspective. It traces the origins and development of this approach since the 1950s, and introduces some of the key theoretical and empirical issues facing it.

Many everyday decisions fall into the category of multiattribute choice problems in which conflicts across a set of attributes can be identified. For example, consumer purchases usually involve a conflict between price and quality. In Chapter 2, Harte and Koele discuss process tracing research into multiattribute decision making and raise important methodological and psychometric issues. First they give an overview of the main research paradigms in this area based on the analysis of information search patterns and verbal protocols. The authors draw a distinction between research intended to describe individual decision processes, and research aimed at testing hypotheses about factors influencing them. They go on to make valuable recommendations of research designs which will yield more reliable descriptions of individual decision processes and more powerful tests of factors influencing these processes. Process tracing techniques are illustrated and discussed in several subsequent chapters. Selart, and Kemdal and Montgomery (Chapters 4 and 5) analyse verbal data while Lewicka and Huber (Chapters 6 and 9) summarise studies which monitor information search. Taken together, then, Chapters 1 and 2 provide the background for the chapters which follow and set them in a broader context.

Chapter 1

Cognitive process models and explanations of decision making

Ray Crozier and Rob Ranyard

Decision making is fundamental to modern life in its individual, collective and corporate aspects. Individuals in the developed world are faced with personal decisions to an extent that previous generations would have found difficult to imagine. A combination of economic, social and technological developments has produced a situation where people have to make important decisions about their relationships and family life, their health, and their education and careers. They are involved in the management of their personal finances as home owners and consumers. Decisions are also fundamental at a societal level. The ballot box is central to democratic political systems as is the jury to the legal system. Business and financial institutions are faced daily with decisions about investment, research and development, and deployment of resources in a complex and uncertain environment.

It is perhaps the social and economic significance of decisions that has resulted in the considerable influence upon psychological approaches to the study of decision making of concepts from other disciplines, in particular, economics. The concepts of utility and subjective probability and theories that account for their integration have shaped psychological enquiry and influenced its research paradigms.

Subjectively expected utility (SEU) theory is a model of rational behaviour, originating in economics and mathematics. This assumes that decisions should be reached by summing over the set of alternatives the utility of each alternative weighted by the subjective probability of its occurrence. Its elegance and authoritative status provide an incentive for decision makers to apply it to their own situation. Nevertheless, the value of utility maximisation as a normative choice principle was criticised, for example, by Simon (1957), who argued that people can successfully adapt to their environment by identifying actions that are merely satisfactory for their goals. He proposed the alternative normative principle of satisficing: take the first course of action that is satisfactory on all important aspects. He argued that this principle could be applied without sophisticated powers of discrimination and evaluation, powers that humans do not possess. He thus developed the concept of bounded rationality, which incorporates the basic assumption that rationality is relative to the information processing capacities of the decision maker. We return to this point below.

Moreover, the status of SEU as a model that describes how people actually make decisions did not receive unequivocal support from empirical studies. Edwards and Tversky (1967:123) summarised the early research as follows:

These studies…generally show consistent, orderly, rational performance. The SEU model is clearly wrong in detail; certain invariances, that should exist if it were right, do not exist. But the sizes of the discrepancies indicate that no one is likely to lose his shirt by making bets that grossly deviate from rationality—whether rationality is defined as maximization of SEU or even as maximization of expected value.

Much of this initial phase of psychological research was concerned with issues of measuring utility and subjective probability. Later research explored empirical findings that one and the same decision problem could produce different decisions either because of variation in the ways in which it was presented or because different response measures were used, even though these were supposed to be equivalent indices of preferences (see Selart, Chapter 4). These findings were difficult to explain in terms of a behavioural model of rational behaviour.

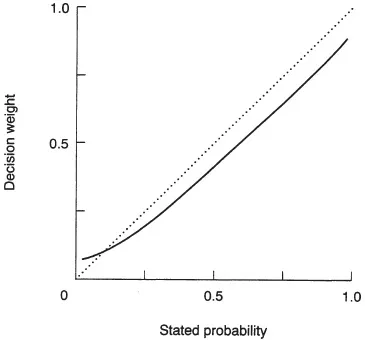

One approach to reducing these discrepancies between behaviour and the SEU theory has been to develop fresh theories that provide a better account of some of these findings. Such theories can be described as ‘structural’, in that they relate decisions to structural characteristics of the decision problem. One of the most influential of these has been prospect theory proposed by Kahneman and Tversky (1979). This theory assumed that, in well-defined risk problems, stated probabilities are translated into subjective weights according to the function shown in Figure 1.1 (Kahneman and Tversky, 1979:283). If the weighting function followed the diagonal line shown on the graph, then decision weights would correspond exactly to stated outcome probabilities. Prospect theory proposes, however, that for very low probabilities weights are higher, but otherwise they are lower than stated probabilities. Kahneman and Tversky note that the function does not represent subjective estimates of probability; rather, it reflects the weight given to well-defined risky prospects in preferential choice situations. The overweighing of very low probabilities predicts some aspects of gambling and insurance behaviour, and the general slope of the function reflects the sensitivity of preference to changes in outcome probability. This treatment of well-defined probabilities is one reason why prospect theory represents a significant advance over SEU theory as a descriptive model of risky decision making. The concept of the decision weight is more coherent than the notion implicit in SEU theory that people distort stated probabilities when they have no good reason to do so. Prospect theory also included a major advance in the way evaluations of outcomes were conceptualised and, in general, it provided a parsimonious account of subjects’ behaviour on several experimental tasks that was difficult to explain in terms of the SEU theory.

Figure 1.1 Prospect theory’s probability weighting function

The erosion of the dominant role played by SEU theory in decision research coincided with changes in psychology more generally. In particular, behaviourist approaches, with their emphasis on the discovery of functional relationships between task variables and behavioural outcomes, were displaced by cognitive psychology. One form of explanation that has been influential in cognitive psychology is the ‘information processing’ model that sets out a sequence of mental operations that takes place between the presentation of a stimulus and the execution of a response. This trend in psychology also had an impact upon research into decision making, particularly in the development of the ‘process’ approach. This is characterised by Svenson (1996:252) as follows:

In process approaches the researcher follows and draws conclusions about the psychological process from problem presentation to decision through collecting process tracing measures, such as information search and think aloud protocols. Hypotheses and theories based on process approach data can later be tested in new process or structural approaches.

The remainder of this chapter examines implications of the process approach for the study of decision making and briefly considers issues that have arisen in research that has been influenced by this approach.

PROCESS STUDIES OF DECISION MAKING

First, we consider the implications of this approach for the methods used to study decision making. It is noteworthy that Svenson’s characterisation assigns a central place to process tracing methods. Second, we identify some significant features of process explanations of decision making. We suggest that these features include: (a) an emphasis upon the temporal dimension of decision making, that is, the decision process is regarded as extended in time; (b) a revitalisation of, and a fresh role for, the concept of decision rule that is associated with the picture of an adaptive decision maker, drawing upon a range of possible strategies in order to reach a decision; (c) the notion that decision makers change their representation of the problem in order to reach a decision. Finally, we consider some trends that can be identified in cognitive psychology that are also evident in decision research. The first of these is a concern with the ecological validity of laboratory methods and the extent to which findings from experimental methods can be generalised to the ‘real world’. The second trend involves the forging of closer links between cognitive and social psychology. The third is an awareness of the important role of affect in cognitive processes.

Process tracing methods

Although some research has used the recording of eye movements in an attempt to capture the information that is sought by decision makers (e.g., Russo and Rosen, 1975), the most frequently used methods have been the information board technique and think aloud protocols. The information board displays information that is relevant to a decision on a number of cards that are arranged on a display that takes the form of an alternatives×attributes matrix (such matrices can also be displayed on a computer, with the participant selecting information by moving and clicking the mouse). For example, the rows of the matrix can refer to a set of alternative apartments and the columns to attributes, such as cost of rent, distance from workplace, size of rooms, and so on. The participant in the study requests information by asking for the information on cards to be made visible, and the sequence of cards requested can be recorded. Attempts can be made to identify the decision strategies adopted by the participants and to test hypotheses about information search on the basis of these sequences (see, for example, Payne, 1976; Koele and Westenberg, 1995). The influence of task variables upon information search can be investigated. For example, Lewicka (Chapter 6) reports evidence that decisions where the goal is to accept one alternative from a set (e.g., to appoint a candidate for a post or to select an article for publication) tend to produce more inspection of the attributes of particular alternatives whereas decisions to reject an alternative produce more inspection of different alternatives on one attribute. In a further example, Maule and Edland (Chapter 11) report that increasing time pressure upon decisions results in more attention being paid to important attribute information about each alternative and, more generally, produces increased use of attribute-based processing relative to alternative-based processing.

The collection of verbal protocols by asking participants to ‘think aloud’ while making a decision has been controversial, since it can be interpreted as representing a return to previously discredited methods of introspection. Hence, it can elicit criticism on the grounds of ‘reactivity’, where the instruction to verbalise changes the process that is the subject of investigation. However, seminal reports by Ericsson and Simon (1980, 1993) set out conditions under which the collection of concurrent verbal protocols could avoid such problems, and a considerable body of research has now used this approach to study decision processes (Ford et al., 1989; Montgomery and Svenson, 1989; Westenberg and Koele, 1994; Payne, 1994).

It is essential to distinguish process tracing via verbal protocols from qualitative approaches or methods of content analysis that have attracted considerable interest among psychologists in recent years. The verbal protocols are treated as data, that is, specific predictions are made about their contents on the basis of process theories. For example, a hypothesis can be tested about the frequency of references to the alternative that is eventually chosen at different points in the decision process. As is the case with information board methods, attempts are made to infer decision strategies from the protocols and to study the influence of task variables. The process approach raises many methodological issues, but we do not pursue these here, as they are examined in depth in the following chapter by Harte and Koele. Finally, it will be evident from the empirical studies reported throughout this volume that the cognitive approach is not restricted to these process tracing methods; a range of experimental methods are used to test hypotheses and to explore decision phenomena.

The temporal dimension

The decision process is regarded as extended in time. One way to construe this is to consider that the process can be divided into a number of phases or stages. These phases can be generated by task analysis. For example, decisions require information so it is only a small step to propose an information acquisition phase. Alternatively, the phases can be generated by theory. Prospect theory assumed that a problem formulation stage involving framing and editing processes precedes an evaluation stage. Montgomery’s (1983) dominance structuring theory proposed that decision making is a search for a dominance structure, an attempt to find a representation of the decision problem such that one alternative is ‘dominant’, i.e., it is superior to all others on at least one attribute and is not inferior to any alternative on any of the other attributes. Search for dominance was hypothesised to go through four phases (Montgomery, 1989:24–5): pre-editing—establishing relevant decision alternatives and attributes; finding a promising alternative; testing whether this promising alternative dominates the other alternatives; dominancestructuring, or transforming the psychological representation of alternatives so that dominance can be achieved. Svenson (1992, 1996; see Chapters 3 and 13, this volume) has developed differentiation and consolidation theory, which also proposes four stages in the decision process: detection of the decision problem; processes of differentiation of an initially chosen alternative from the other alternatives; the decision stage; the post-decision consolidation stage, to support the implementation of the decision and to protect the decision maker from regret at having made the wrong decision.

Svenson’s theory assigns considerable weight to post-decision processes; not only are they viewed as importa...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- List of figures and tables

- Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Part I Fundamentals

- Part II Values and involvement

- Part III The risk dimension

- Part IV The time dimension

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Decision Making by Ray Crozier,Rob Ranyard,Ola Svenson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.