1 Assessment: to measure or to learn?

Standards are rising

Standards are going up in English schools. This at least is the judgement of the Office for Standards in Education (OFSTED), based on its inspections of schools during recent years. Both the 1999 Chief Inspector’s report on English primary schools and the 1998 review of secondary education in England report rising levels of performance. For example, in primary schools:

The quality of education in primary schools has improved… More children are achieving higher standards by the time they transfer to secondary school. At Key Stage 2 there has been a substantial increase in the proportion of pupils achieving Level 4 in English and mathematics. This proportion has risen by about 15 percentage points over the four years.

(OFSTED, 1999:9)

The 2001 National Curriculum assessment test results for Key Stages 1, 2 and 3 in England tell a similar story. In most areas progress has been made towards the targets set by the government for schools and Local Education Authorities (LEAs). So far, so good. There can be little doubt that the enormous effort that the government has put into raising standards in recent years has borne fruit.

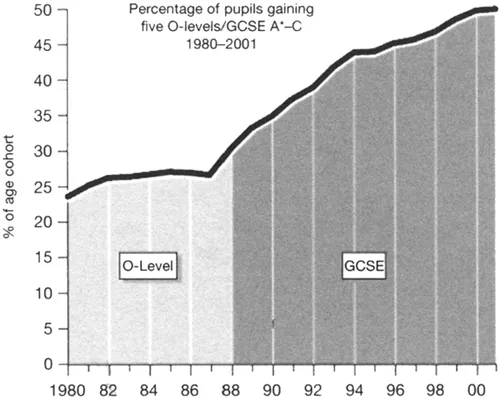

Equally there is evidence from national examination results, GCSE and A level, that standards are going up at this level too. The government has met its target of 50 per cent of pupils achieving five or more GCSE at grades A*–C or the GNVQ equivalent a year early (2001 rather than 2002). This has increased from 46.3 per cent in 1997 when the targets were announced.

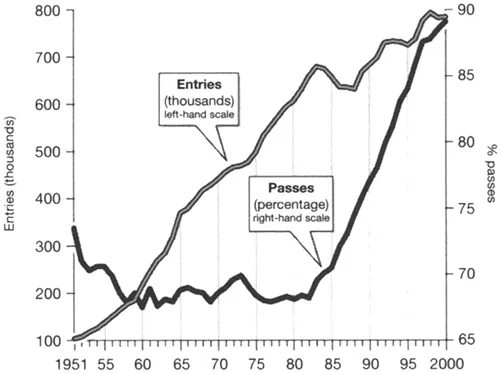

Both Figure 1.1 and Figure 1.2 show how the grades achieved have risen over time. What does the rise in measured standards really mean? Are pupils better learners? Is teaching getting better? Are examinations getting easier? Despite the yearly complaints that GCSE and A-level examinations are getting easier, reports from the Qualifications and Curriculum Authority (QCA, 2001c) suggest there is no evidence to support this claim. So what is happening?

Are pupils becoming better learners?

Undoubtedly teachers are becoming better at preparing pupils to perform in these national tests. Does that mean that pupils are becoming better learners? Does the current emphasis on formal summative assessment in the shape of external tests and exams mean that pupils are becoming better equipped to be lifelong learners in the twenty-first century? Are pupils learning the right things in school? Are some pupils demotivated by assessment? Are we indeed paying a price for the growing emphasis on performance that is necessarily dominating teachers’ and pupils’ minds in today’s schools? If so, what can teachers do about it? In this book we seek to answer this question. We also explore some implications of the headlong pursuit of higher standards.

Can assessment play a more constructive role in the process of learning itself? Are there different kinds of assessment that should be being pursued if we are to equip young people for the world of the twenty-first century? What’s in it for schools, teachers and pupils in terms of changed assessment practices? This book explores these questions from the perspective of both teachers and pupils.

Are schools and teachers using assessment to promote learning?

The answer, coming from a range of sources, suggests that while assessment practice has improved over the years, teachers could achieve still more if they used the information they gather about pupils’ learning more effectively to plan and teach their lessons. Pupils’ experience and understanding of assessment is an important factor in raising standards. While pupils are better at doing examinations what do they understand of the assessment they experience, and is the quality of their learning better?

Figure 1.1 O-level and GCSE results (1980–2001)

Source: Times Education Supplement (23 Nov. 2001): 23

Figure 1.2 Ascent of the A-level (1951–2000)

Source: Times Education Supplement (23 Nov. 2001): 23

Figure 1.3 ‘Standards are rising’—are pupils becoming better learners?

Much of the material we draw on to answer these questions comes from a research project (the LEARN project) conducted during 1999 and funded by the Qualifications and Curriculum Authority (QCA). LEARN was designed to find out both how pupils viewed themselves as learners and also their views on the interaction between assessment and the learning process in school. A wide age range of pupils, from the early years of primary schooling through to the end of the sixth form, were interviewed. We describe the project in more detail in Chapter 3, but as later chapters of this book reveal, the results were startling. They show a picture of young people unclear about what they are supposed to be learning and why; unclear about their own strengths and weaknesses as learners; unclear about the feedback they receive from teachers about how to improve and progressively more dependent on the teacher to guide their learning.

Figure 1.4 ‘What do we have to do?’ ‘Don’t worry—just do what I tell you.’

Is the current assessment regime asking the right questions?

If the findings of the LEARN project are a valid representation of pupils in schools in England today there is grave cause for concern. The pupils’ responses suggest that despite achieving higher standards in formal tests, they are no more empowered as independent learners than before, indeed perhaps even less so, as the obsession with doing well continues to increase. Instead what emerges is that while pupils are better prepared to pass particular tests, they are not necessarily better equipped to use their knowledge and skills effectively in other contexts. Schools meanwhile, under pressure to retain or improve their place in published league tables and to meet specified achievement targets, have little time or energy to consider apparently more ephemeral issues concerning the nature of learning and pupils’ engagement with it.

We hope that this book will challenge this mind set; that it will encourage teachers to consider the powerful role that assessment plays in the promotion or inhibition of learning and to take the longer view about the kinds of learning which will be important for pupils if they are to be equipped for life and work in the changed world of the twenty-first century.

How can learners be empowered?

What are the potential consequences of the growing emphasis on extrinsic motivation, on trading for grades, rather than the creation of learners who are empowered in more intrinsic ways? What is the impact on learning, particularly for lower achievers, of the fear and anxiety that the intense diet of external testing is creating? What are the implications for society of pupils who are less and less willing to take risks in their learning? How important are issues of creativity?

These are big questions and are perhaps best illustrated by the story of one pupil, Jenny, as described by her mother:

I notice the pain and anguish that my daughter, aged 7, is currently going through as she realises, much earlier than I did, how assessment goalposts can change. I think that my early and continued academic successes shield me from some of the social realities that she has to come to terms with much earlier in her life. Jenny is bright and thoughtful and a good reader (phew!). Unluckily she has some specific writing difficulties, partly because she genuinely doesn’t care about how things are spelt (not a favourite with David Blunkett) and partly because she has enormous difficulty writing quickly and legibly. She is young for her age and my version is that this will develop. Although she is off the scales on the reading and mental maths stakes, her teachers this year have put her in the ‘derrh brains’ group, because she never finishes her work and it is often illegible. She is humiliated.

Throughout the infants school she was an achiever. She took part in plays, played the violin and the piano, was given certificates and awards for art, for being a good friend, for being a good musician, for helping catalogue the library etc. She even got a certificate in assembly for holding a Blue Peter bring and buy sale and she felt successful. Now she feels a failure. The goalposts have changed and she can only get a smiley face on her chart for two things—spelling and times tables tests. If the whole family busts a gut for the week she sometimes gets all her spellings right, but only once has there been a smiley face for maths. She writes it down wrong or too slowly.

Jenny has entered sullen adolescence overnight and partly I feel distraught for her, but listening to her work out the ludicrousness of the test culture and the boring and unadventurous place her school has become for her I also wonder if she has made an important discovery that will stand her in good stead. She knows she is still good at the things that used to be valued, she also knows that they are not important any more to school but that they are very important to us. As she recently pointed out to her intractably naive mother, ‘It doesn’t matter about understanding things in the juniors, just as long as we get them right. I mean there’s no time to go into understanding stuff. That all takes ages and you have to have a go. In the juniors there’s a lot less having a go and a lot more getting told things’.

This theme is taken up by David Almond, the author of the prize-winning children’s book Skellig and himself a former teacher. Lamenting the stifling of creativity in schools he predicted that in 50 years’ time:

the concentration on assessment, accreditation, targets, scores, grades, tests, profiles will be seen as a kind of madness…. The pedants are triumphant and go about their task of disintegrating our world…like medieval philosophers they debate the exact weight to be given to every fragment, 15% on this subject, 12.5% on that, 5.7% on the other. There’s an arrogance at work. The arrogance that we know exactly what happens when someone learns something, that we can plan for it, that we can describe it, that we can record it and that if we don’t do these things then the learning doesn’t exist. The arrogance leads us to concentrate on a particular kind of work, noses to the grindstone treadmill kind of work, work that is observable, recordable and well nigh constant. So,…get kids into school fast. Get them assessed while they are in nappies. Get them going in literary clubs, numeracy clubs, lunch time learning clubs, holiday learning clubs. Holidays—let’s cut them. School day—let’s lengthen it. Homework—one hour, no let’s make it two. Let’s see them, children and teachers, work, work, work and let’s get plenty of people watching them and recording them while they’re at it. What would the assessors and recorders have made of Archimedes splashing happily about in his bath before he yelled ‘Eureka!’ What would they have made of James Watson snoring in his bed as he dreamt the molecular structure of DNA?

(Alberge, 1999:8–9)

David Almond’s personal view, as quoted above by Alberge, is supported by the findings of a major research study [the Primary, Assessment, Curriculum and Expectations (PAGE) project] (Pollard et al., 2000) that documented the impact of the National Curriculum and national assessment on pupils’ learning in primary schools. The study concluded that:

the combined effect of recent policy changes in assessment has been to reinforce traditionalist conceptions of teaching and learning which are associated with a greater instrumentalism on the part of pupils. From this it can be argued that rather than acquiring lifelong learning skills and attitudes, the effect of recent reforms has been to make pupils more dependent on the teacher and less ready and able to engage in deep learning.

(Broadfoot and Pollard, 2000:24)

But does this matter? As long as pupils are learning the curriculum that is being delivered to them, should we not be content that all is well in the world of education and assessment?

In the end it all depends what you mean by learning. In England, teachers have never defined their role simply as the transmission of knowledge to pupils. Their commitment has always been a more broadly based one of seeking to excite in their pupils a love of learning and of creating an environment in which this can happen. Now these traditional professional orientations are increasingly being underpinned by the recognition that a rapidly changing world requires new types of learning. The explosion of new learning opportunities already available through the world wide web and other forms of new opportunity requires each individual to develop the capacity to chart their own route, their own learning map, their own individual targets for learning. They need to be capable of choosing such options, of managing risk in a complex and unpredictable environment. In life, as in work, they will need to have the creativity to generate new solutions to problems and last but not least, they will need to have the self-reliance, the resilience, to fall back on their own resources in an increasingly fragmented world. In short, as Guy Claxton (1998) has put it, they will need to ‘know what to do when they don’t know what to do’.

If this is the vision of the future, it has significant implications for curriculum and teaching methods on the one hand, and for the orientation of students to their learning on the other. At its heart it requires pupils to become learners who are self-motivating and empowered within the learning process. As Steinberg has so trenchantly put it, ‘no curricula overhaul, no instructional innovation, no change in school organisation, no toughening of standards, no rethinking of teacher training or compensation will succeed if students do not come to school interested in, and c...