![]()

PART I

Introduction

![]()

1

SOCIALLY ENGINEERING THE ROAD YO UTOPIA

So long as there are men there will be wars.

Albert Einstein

The summer before I began writing this book I spent time with my family traveling in Asia, throughout the remarkable landmarks of China, the rainforests and rice fields of Vietnam, the pristine beaches and waters of Thailand, and the beautiful but war-ravaged and still war-recovering Cambodia. While the whole trip was indeed moving, what I found most inspiring was our time well spent in Cambodia. Walking the ancient temples of Angkor Wat, meeting some of the kindest people in the world, especially given their palpable Buddhist and Hindu principles and beliefs, and experiencing everything we possibly could of Cambodian culture.

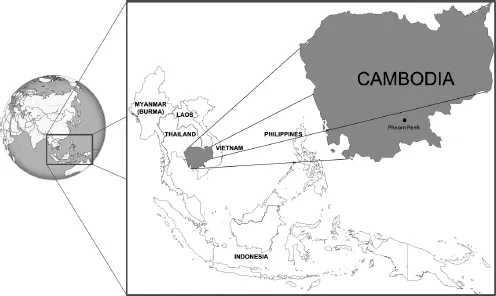

To my chagrin, I did not know until my arrival (or recall from my courses in world history) that the country recently survived one of the bloodiest genocides in history, one that occurred as recently as 1975 at the end of the Vietnam War, following America’s invasion of Cambodia and following Nixon’s carpet bombing of the Viet Cong occupying the country’s eastern borders (see Figure 1.1).

Soon after America withdrew its forces, the country’s capital city, Phnom Penh, fell, and the communist regime of the Khmer Rouge ascended. If you recall the Academy Award winning movie, The Killing Fields, you might remember the story, and the true account of a Cambodian photojournalist, Dith Pran, who befriended the New York Times correspondent, Sydney Schanberg. Schanberg by happenstance abandoned Pran nearing tyrant Pol Pot’s bloody “Year Zero” takeover and cleansing campaign (Putnam, Smith, & Joffé, 1984).

The idea behind the “Year Zero” crusade was that in order for the communist Khmer Rouge regime to rule supreme (1975–1979), everything including the country’s cultures, traditions, and many of its people had to be purged. This led to “necessary violence” and mass genocide which claimed the lives of approximately two million objectionable civilians of the then nearly eight million who resided in the country. The “undesirables” who were targeted and ultimately executed (or died of starvation, disease, torture, or in labor camps in the killing fields) included the country’s most educated, specifically Cambodia’s professors and teachers, doctors, lawyers, police and businessmen and women, artists, musicians, writers, and the like. All who were deemed professionals, intellectuals, or even literate because they wore eyeglasses were pejoratively viewed as oppressive and subversive, and singled out for extermination. They were besieged for their alleged capacities to resist the Khmer Rouge’s ultimate end – a utopian, self-sufficient, agriculturally focused, ethnically pure, and classless, communist-controlled state.

| Figure 1.1 | Map of Cambodia. |

While the Cambodian photojournalist, Pran, was one of the “undesirables,” he barely survived, undercover as his peasant alter ego – an uneducated taxi cab driver. He eventually escaped by walking his way out of the killing fields, only to discover that more than 50 of his family members had been killed. He lived the rest of his life working in the U.S. as a photographer for the New York Times and relentlessly promoting global awareness about the Cambodian Holocaust. He passed away in 2008 at the age of 65, with his horrific thoughts and memories “still alive to [him] day and night” (Dith Pran, 2004; see also Farrell & Rummel, 2008; Martin, 2008). In his “Last Words” interview with the New York Times, Pran noted that “in order to survive, you [had] to pretend to be stupid, because they [did not] want you to be smart. They [thought] that the smart people [would] destroy them … you [had] to show that you [were] not a threat to [survive]” (Farrell & Rummel, 2008). The Khmer Rouge’s attempts to contrive and influence attitudes and social behaviors by cleansing (i.e., social engineering by genocide) still haunt the Cambodian people today.

What is resounding is that mass murder and methodical cruelty as preludes to utopia have occurred in many ways during many times and in many parts of the world in the past. Social engineering by genocide, whether via religious, racial, ethnic, or national group cleansing, is not a new historical phenomenon. In terms of religious cleansing, during the Middle Ages, a period generally fraught with intellectual obscurity and atrocity, inquisitional courts implicated, indicted, and burned at the stake perceived heretics who spoke out about or against, or thought differently from the politically dominant Catholic Church. With regards to racial cleansing, within the last century the Nazi-sponsored Holocaust aimed to completely exterminate the Jewish race, the race that according to Hitler was not a religion. This ultimately resulted in the execution of six million Jews and the slaying of five million other “undesirables” including homosexuals, gypsies, people with disabilities, and other political and religious adversaries. Regarding ethnic cleansing, just 20 years ago, nearly one million people in Rwanda were murdered due to ethnic tensions between the Tutsi and Hutu peoples. Concerning national groups, America’s actions in the name of Manifest Destiny are also considered by many to qualify as social engineering by genocide. The numbers of Native Americans and Mexican nationals who perished during times of rationalized expansion and redemption are comparable to the fatalities recorded during the Nazi-sponsored Holocaust (Cesarani, 2004; see also Smith, 2013).

While all these persecutors used various forms of genocide to socially engineer the roads to their interpretations of utopia, however, none of these instances matched what occurred in Cambodia, not in terms of the sheer numbers of deaths or types of terror, but in terms of goals and objectives. The Khmer Rouge’s deliberate and systematic efforts to destroy a group of perceived intellectuals (not to say that these groups were not intellectuals themselves) and the regime’s efforts to extinguish their allegedly threatening and abhorred ideas, add much to our thinking about intellectual genocide and social engineering. In Cambodia, intellectual genocide was used to promote communism, thwart any hopes or prospects of a democratic state, and turn the country over to a state of the people, where the people were defined as the country’s workers, farmers, laborers, and peasants. In the end, the Khmer Rouge’s aims and actions to exterminate all intellectuals and socially engineer a totalitarian and utopian dictatorship devastated the country instead. The country is still in the process of healing and recovery (Jenkins, 2012).

Social engineering in the political sciences

However, while social engineering is often viewed negatively, particularly, for obvious reasons, in cases of social engineering by intellectual, religious, race, ethnic, or national group genocide), social engineering by other means is quite common in the political sciences. Most governmental and private groups, in their efforts to promote or protect private or the public’s perceived interests, attempt to methodically sway or change public attitudes and behaviors in one way or another. While the goal remains the same – to control or influence society, the polis, or city-state by eliminating or reducing human agency or agents (Marx, 1995) – in the political sciences, social engineering relies on more subtle means. Here, social engineers use other powerful instruments to influence attitudes and social behaviors, ultimately to promote and promulgate a societal, oft-utopian ideal. Social engineering tools include scare tactics; propaganda and rhetoric often vetted through mass media outlets; generalizations, assumptions, and rationalizations; and incentives and disincentives to ultimately engineer the social behaviors desired.

It should be mentioned that social engineering is not always adversarial, however. For example, at the end of the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln used highly controversial tactics to socially engineer the country’s path to free the slaves of the Confederate South. His notorious actions, along with his remarkable leadership, led to his Emancipation Proclamation of 1863, which ultimately led to the adoption of the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1865. This made slavery and involuntary servitude illegal throughout the U.S. This serves as a prime example of how governmental policies also constitute a powerful social engineering tool, again when control is the means and a utopian ideal the end. The emancipation of the slaves in the South was certainly at the time utopian, while more often than not perceived as impractical and unreasonable.

By definition, a public policy is in itself a tool used by governments to define a course of action that will ultimately lead to a high-level, supreme, and desirable end. Sometimes public policies can be unwise, however, when seemingly principled means produce unintended, unanticipated, and perverse consequences instead. Often, the inadvertent effects outweigh the intended consequences for which the policy was engineered in the first place, as social engineers’ attempts to control and alter their environments are imperfect and often contradict or distort what is virtuous, pure, and good (Campbell, 1976; Wheatley, 1992).

In 1962, for example, Rachel Carson published her acclaimed book Silent Spring – the book now widely credited with initiating the environmental movement and the founding of the Environmental Protection Agency. In it, Carson wrote lucidly and passionately about the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s assault on the environment. She criticized the department for turning a blind eye, and disregarding the many empirical research studies from which she drew her conclusions but that were not new or inaccessible, just conveniently ignored (Griswold, 2012). She also criticized the department’s ignorant and purchased acceptance of the chemical industry’s oratorical, “research-based,” and lobbied claims that their synthetic pesticides, from which they were profiting, were the best to control and kill agricultural pests. In fact, the government’s excessive spraying of DDT (dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane) was at one time so universally accepted that the public forgot to question its use. That is, until Carson wrote Silent Spring, which ultimately led to the banning of DDT in 1972, at least in the domestic U.S.A.1

Here, the public, having been socially conditioned, naively trusted that simply because the pesticide was familiar, it was safe and effective. The public’s opinion had been socially engineered into believing DDT and other harsh pesticides were necessary and harmless. Unfortunately, however, what ended up being destroyed were the ecosystems into which the pesticides were introduced.

The culprits included those who socially engineered the severity of the problem, those who amplified public alarm about the problem, those who chemically manufactured the solution to the problem, those who marketed false promises about the solution to the problem, and those who subsequently profited by having provided the best, if not only solution to the problem turned severe. The unintended effect was that what the government and industrialists provided to control the problem caused effects markedly worse than the problem needing to be controlled in the first place (agricultural pests). Metaphorically speaking, the spring had gone silent because of the absence of the non-pest wildlife that the synthetic pesticides also killed (Carson, 1962; Griswold, 2012; see also Amrein-Beardsley, 2009b).

Social engineering via the use of federal and state tax policies to encourage or discourage societal behaviors has also become commonplace. This is especially true with the U.S. Department of the Treasury and its use of tax credits, breaks, deductions, and exemptions since the passage of the Tax Reform Act of 1986. The rationale is that via the tax system and its provisions, many societal behaviors and activities can be encouraged using incentives for things like charitable giving, homeownership, and the purchase of health insurance. Similarly, many societal behaviors and activities can be discouraged through disincentives like “sin” taxes to reduce alcohol and tobacco use or gambling. More recently “fat” taxes have been designed and introduced to curb the sedentary activities seen as contributing to America’s obesity epidemic. Empirical evidence substantiating that the use of federal and state tax policies to encourage or discourage, or socially engineer these or other societal behaviors in fact works is scarce, however.

The most obvious of unintended consequences that come along with such (dis)incentive systems are tax distortions. Such distortions often come about as a result of system gaming techniques, whereby for those who are best equipped to understand and manipulate the incentives and disincentives put into place can exploit them to their advantage. Take, for example, the recent scandal with Apple Inc., whereby Apple CEO Tim Cook and associates have continued to use opposing taxation loopholes in Ireland and the U.S. to avoid paying billions in taxes. The U.S. Senate subcommittee investigating Apple also investigated Microsoft, Hewlett-Packard, and other multinational companies, charging that they too have exploited loopholes in the U.S. federal tax code avoiding billions in U.S. taxes as well (Associated Press, 2013).

The unintended effects that come along with such (dis)incentive s...