This is a test

- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

De-Scribing Empire is a stunning collection of first-class essays. Collectively they examine the formative role of books, writing and textuality in imperial control and the fashioning of colonial world-views. The volume as a whole puts forward strategies for understanding and neutralising that control, and as such is a major contribution to the field. It will be invaluable for students in post-colonialist criticism.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access De-Scribing Empire by Alan Lawson,Chris Tiffin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

POST-COLONIAL THEORY

1

THE SCRAMBLE FOR POST-COLONIALISM

Stephen Slemon

It is scarcely news to readers of this volume that the heterogeneous field of ‘post-colonial studies’ is reproducing itself at present as a spectacle of disorderly conduct. Perhaps this is as it should be for a field which takes for its academic objective a wholesale refashioning of the Western project of the traditional ‘humanities’; but I think it is clear that the institutionalized field of post-colonial studies, at least, has arrived at a point of multiple intersections, of ruptures, of territoriality—and this suggests that the field has arrived at a point that really matters in its history. In this essay, I want to try to think through the dis/order imbricated in the post-colonial academic field, and in part to respond to the ways in which a policing energy seems to carry itself across a variety of articulations within the postcolonial problematic. The policing energy which interests me here is in the final instance an internalized apparatus for control and regulation, an effect of ideology, and I am not about to argue that ‘out there’ in post-colonialdom there are double agents, neocolonialist conspirators, wolves-in-sheep’s-clothing, whom ‘we’ must resist through some vigorous form of oppositional collectivity. But I am going to suggest that as the field of post-colonial studies is becoming professionalized as an institution for social critique and as an apparatus for producing cultural knowledge, it is beginning to perform within itself a regulating operation which has no necessary relation to, or investment in, a politics of anti-colonialism. This article, consequently, is an attempt to carry out some (ideological) refereeing in this structure of professionalized or disciplinary regulation: I want to address the question of who gets to play on the post-colonial field, who is asked to sit on the bench, who plays on the farm team, how and when a player is, or ought to be, called ‘out’. Now obviously, I am in no sense outside of these questions; I too have an institutional stake in this game and am part of the disciplinary scramble. My refereeing persona here must necessarily be ambivalent, compromised by a double articulation in meta-regulation and in wager. Nevertheless, for the purposes of this exercise, I want to pretend to stand somehow outside the ‘field’.

My thesis here is that in one register, the scramble now taking place within critical theory over the valency of the ‘post-colonial’ marker is at heart an institutional scramble, a debate whose specific provenance is an emerging critical and pedagogical field within the apparatus of the Western ‘humanities’. My general argument is that the site of rupture for post-colonial studies is, in fact, predicated by a set of possibly unresolvable debates in the related field of colonial discourse theory, and more distantly in ‘humanities’; and the conclusion I will be reaching for is a highly personal and I suspect ungeneralizable credo that has to do with the practice of anti-colonialist empowerment. But the question I will be pursuing on the way to this conclusion is why it is—and why it should be—that some radically differential, and in fact methodologically hostile, critical and teaching practices seek a grounding in something called ‘post-colonialism’ in order to de-scribe their various Empires and engage in an emancipatory and local institutional politics.

1

‘Post-colonialism’, as it is now used in its various fields, de-scribes a remarkably heterogeneous set of subject positions, professional fields, and critical enterprises. It has been used as a way of ordering a critique of totalizing forms of Western historicism; as a portmanteau term for a retooled notion of ‘class’, as a subset of both postmodernism and post-structuralism (and conversely, as the condition from which those two structures of cultural logic and cultural critique themselves are seen to emerge); as the name for a condition of nativist longing in post-independence national groupings; as a cultural marker of non-residency for a Third World intellectual cadre; as the inevitable underside of a fractured and ambivalent discourse of colonialist power; as an oppositional form of ‘reading practice’; and—and this was my first encounter with the term—as the name for a category of ‘literary’ activity which sprang from a new and welcome political energy going on within what used to be called ‘Commonwealth’ literary studies. The obvious tendency, in the face of this heterogeneity, is to understand ‘post-colonialism’ mostly as an object of desire for critical practice: as a shimmering talisman that in itself has the power to confer political legitimacy onto specific forms of institutionalized labour, especially on ones that are troubled by their mediated position within the apparatus of institutional power. I think, however, that this heterogeneity in the concept of the ‘post-colonial’ —and here I mean within the university institution—comes about for much more pragmatic reasons, and these have to do with a very real problem in securing the concept of ‘colonialism’ itself, as Western theories of subjectification and its resistances continue to develop in sophistication and complexity.

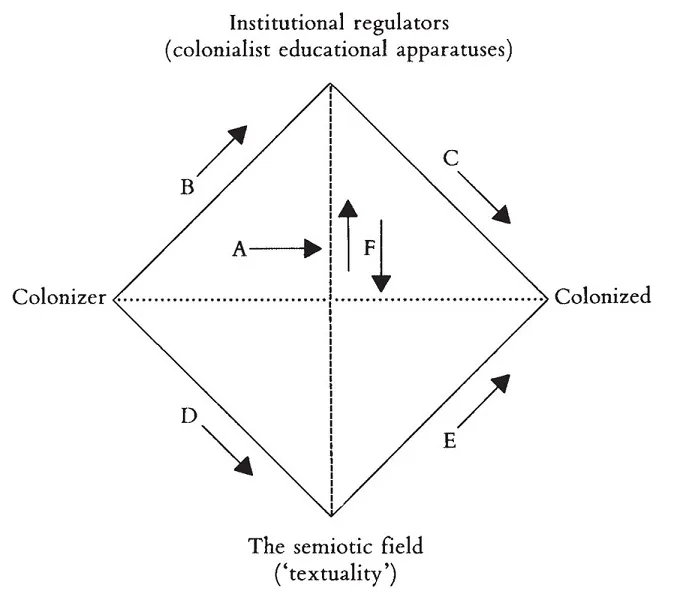

The nature of colonialism as an economic and political structure of cross-cultural domination has of course occasioned a set of debates, but it is not really on this level that the ‘question’ of European colonialism has troubled the various post-colonial fields of study. The problem, rather, is with the concept of colonialism as an ideological or discursive formation: that is, with the ways in which colonialism is viewed as an apparatus for constituting subject positions through the field of representation. In a way—and of course this is an extreme oversimplification—the debate over a description of colonialism’s multiple strategies for regulating Europe’s others can be expressed diagramatically (see Figure 1.1).

The general understanding in Figure 1.1 is that colonialism works on a left-to-right order of domination, with line ‘A’ representing various theories of how colonialism oppresses through direct political and economic control, and lines ‘BC’ and ‘DE’ representing differing concepts of the ideological regulation of colonial subjects, of subordination through the manufacture of consent. Theories that recognize an efficacy to colonialism that proceeds only along line ‘A’ are in essence ‘brute force’ or ‘direct political’ theories of colonialist oppression: that is, they reject the basic thesis that power manages social contradiction partly through the strategic production of specific ideas of the ‘self’, which subordinated groups then internalize as being ‘real’. Theories, however, that examine the trajectory of colonialist power primarily along line ‘BC’ —a line representing an ideological flanking for the economic colonialism running along line ‘A’ —focus on the constitutive power of state apparatuses like education, and the constitutive power of professional fields of knowledge within those apparatuses, in the production of colonialist relations. Along this line, Edward Said (1979) examines the political efficacy of ‘orientalism’ within colonialism; Talal Asad (1973) and many others examine the role of anthropology in reproducing colonial relations; Alan Bishop (1990) examines the deployment of Western concepts of ‘mathematics’ against African school-children, Timothy Mitchell (1988) examines how the professional field of ‘political science’ came into being through a European colonialist engagement with the cultures of Egypt; Gauri Viswanathan (1989) examines the foundations of ‘English’ literary studies within a structure of colonialist management in India. This work keeps coming in, and the list of radically compromised professional fields within the Western syllabus of ‘humanities’ options grows daily longer. Theories that focus primarily on line ‘DE’ in this diagram examine the ways in which ideology reproduces colonialist relations through the strategic deployment of a vast semiotic field of representations—in literary works, in advertising, in sculpture, in travelogues, in exploration documents, in maps, in pornography, and so on.

Figure 1.1 Diagram representing the debate over the nature of colonialism.

This pattern, as I have laid it out so far, does not seem especially controversial or problematic, but the difficulties arise at the moment of conceptualizing the relation between colonialist professional fields and institutions (at the top of the diagram) and the whole field of representation (at the bottom of the diagram) — the field of ‘textuality’ and its investment in reproducing and naturalizing the structures of power. To take up one example of this paradigmatically: in Edward Said’s work on Orientalism, colonialist power is seen to operate through a complex relationship between apparatuses placed on line ‘F’, where in the first instance a scholarly educational apparatus called ‘Orientalism’ —at the top of the line—appropriates textual representations of ‘the Orient’ in order to consolidate itself as a discipline and to reproduce ‘the Orient’ as a deployable unit of knowledge. So, in the first instance, colonialist power in Said’s argument runs not just through the middle ground of this diagram but through a complex set of relations happening along line ‘F’; and since Said’s thesis is that a function at the top of this line is employing those representations created at the bottom of the line in order to make up ‘knowledges’ that have an ideological function, you can say that the vector of motion along line ‘F’ is an upward one, and that this upward motion is part of the whole complex, discursive structure whereby ‘Orientalism’ manufactures the ‘Orient’ and thus helps to regulate colonialist relations. That is Said’s first position: that under Orientalism the vector of line ‘F’ is upward. But in Said’s analysis, colonialist power also runs through line ‘F’ in a downward movement, where the scholarly apparatus of Orientalism is understood to be at work in the production of a purely fantastic and entirely projected idea of the ‘Orient’. The point is that in the process of understanding the multivalent nature of colonialist discourse in terms of the historical specific of ‘Orientalism’, Said’s model becomes structurally ambivalent—under ‘Orientalism’, the ‘Orient’ turns out to be something produced both as an object of scholarly knowledge and as a location for psychic projection.1I have graphed this ambivalence as a double movement or vector along line ‘F’. For Said, the mechanism that produces this ‘Orient’, then, has to be understood as something capable of deploying an ambivalent structure of relations along line ‘F’, and deploying that structure towards a unified end. And so Said (and here I’m following Robert Young’s analysis of the problem) ends up referring the whole structure of colonialist discourse back to a single and monolithic originating intention within colonialism, the intention of colonialist power to possess the terrain of its Others. That assumption of intention is basically where Said’s theory has proven to be most controversial.

Said’s text is an important one here, for as Robert Young has shown, Said’s work stands at the headwaters of colonial discourse theory, and this ambivalence in Said’s model may in fact initiate a foundational ambivalence in the critical work which comes out of this field. This ambivalence sets the terms for what are now the two central debates within colonial discourse theory: the debate over historical specificity, and the debate over agency.

The first debate—the debate over the problem of historical specificity in the model—concerns the inconclusive relation between actual historical moments in the colonialist enterprise and the larger, possibly trans-historical discursive formation that colonial discourse theory posits in its attempt to understand the multivalent strategies at work in colonialist power. Can you look at ‘colonial discourse’ only by examining what are taken to be paradigmatic moments within colonialist history? If so, can you extrapolate a modality of ‘colonialism’ from one historical moment to the next? Does discursive colonialism always look structurally the same, or do the specifics of its textual or semiotic or representational manoeuvres shift registers at different historical times and in different kinds of colonial encounters? And what would it mean to think of colonial discourse as a set of exchanges that function in a similar way for all sorts of colonialist strategies in a vastly different set of cultural locations? These questions of historical specificity, though always a problem for social theory, are especially difficult ones for colonialist discourse theory, and the reason for this is that this theory quite appropriately refuses to articulate a simplistic structure of social causality in the relation between colonialist institutions and the field of representations. In other words, colonial discourse theory recognizes a radical ambivalence at work in colonialist power, and that is the ambivalence I have attempted to show in Figure 1.1 as a double movement in vector at the level of line ‘F’.

To clar ify this, I want to make use of Gauri Viswanathan’s important work on Britain’s ideological control of colonized people through the deployment of colonialist educational strategies in nineteenth-century India. Obviously, the question of what happens along line ‘F’ in Figure 1.1 can only be addressed by specific reference to immediate historical conditions, and every piece of archaeological work on colonialist power will want to formulate the vector of action here with particular sensitivity to the local conditions under analysis. Viswanathan researches this part of the puzzle with exemplary attention to history, and at heart her argument is that colonialist education in India (which would stand in as the ideological apparatus at the top of the diagram) strategically and intentionally deployed the vast field of canonical English ‘literature’ (the field of representations at the bottom of the diagram) in order to construct a cadre of ‘native’ mediators between the British Raj and the actual producers of wealth. The point here is that Viswanathan’s analysis employs a purely upward vector of motion to characterize the specifics of how power is at work along line ‘F’ in the diagram, and what secures this vector is Viswanathan’s scrupulous attention to the immediate conditions that apply within British and Indian colonial relations.

The problem, though—and here I mean the problem for colonial discourse theory—is that the foundational ambivalence or double movement that Said’s work inserts into the model of colonialist discourse analysis always seems to return to the field; and it does so through critical work that on its own terms suggests a counter-flow along line ‘F’ at the same moment of colonialist history. That is, the residual ambivalence in the vector of line ‘F’ within colonial discourse theory seems to invite the fusion of Viswanathan’s kind of analysis with critical readings that would articulate a downward movement at this place in the diagram; and one of the areas such work is now entering is the analysis of how English literary activity of the period (at the bottom of line ‘F’) suddenly turned to the representation of educational processes (at the top of the line), and why this literature should so immediately concern itself with the investments of educational representations in the colonialist scene. In examining the place of English literary activity within this moment of colonialist history, that is, a critic such as Patrick Brantlinger would want to argue for the valency of texts such as Jane Eyre or Tom Brown’s School Days within colonialist discursive power, and colonialist discourse theory would want to understand how both kinds of discursive regulation, both vectors of movement along line ‘F’, are at work in a specific historical moment of colonialist relations. Because of Said’s ambivalence in charting out the complex of Orientalism along line ‘F’, I am arguing, the field of colonialist discourse theory carries that sense of ambivalence forward, and looks to an extraordinary valency of movement within its articulation of colonialist power. The ambivalence makes our understanding of colonial operations a great deal clearer for historical periods, but it also upsets the positivism of highly specific analyses of colonialist power going on within a period.

The basic project of colonial discourse theory is to push out from line ‘A’, and try to define colonialism both as a set of political relations and as a signifying system, one with ambivalent structural relations. It is remarkably clarifying in its articulation of the productive relations between seemingly disparate moments in colonialist power (the structure of literary education in India, the literary practice of representing educational control in Britain), but because it recognizes an ambivalence in colonialist power, colonial discourse theory results in a concept of colonialism that cannot be historicized modally, and that ends up being tilted towards a description of all kinds of social oppression and discursive control. For some critics, this ambivalence bankrupts the field. But for others, the concept of ‘colonialism’ —like the concept of ‘patriarchy’ for feminism, which shares this structure of transhistoricality and lack of specificity—remains an indispensable conceptual category of critical analysis, and an indispensable tool in securing our understanding of ideological domination under colonialism to the level of political economy.

The first big debate going on within colonialist discourse...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- ILLUSTRATIONS

- NOTES ON CONTRIBUTORS

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- INTRODUCTION

- PART I POST-COLONIAL THEORY

- PART II RACE AND REPRESENTATION

- PART III READING EMPIRE

- PART IV RE-WRITING AND RE-READING EMPIRE

- BIBLIOGRAPHY