III: Military developments

G. A. Hayes-McCoy calculated that there were more than 200 military engagements of varying degrees of importance and size in Ireland from the medieval period to 1798. The more important of these are shown in Figure 9; they demonstrate that with the coming of the Norman invaders (12) the Irish began a military struggle that was to continue over four centuries. Before the Norman invasion, Irish military history was dominated by confrontations with the Norse invaders (11), although internecine strife between Irish aspirants to kingship was a feature of Irish life from the beginning of recorded history.

The major engagements of the medieval period are, however, those of defenders against invaders: most were fought in an attempt to prevent further Norman penetration of the country. That the Irish succeeded in preventing the Normans from completely overrunning the country was due not only to stout resistance but also to the isolation of the invaders from their homeland and the impossibility of their securing sufficient reinforcements to maintain and consolidate their position. Additionally, the importation by the Irish of Scots mercenary soldiers called galloglas (from gall óglach – foreign warrior) from the thirteenth century onwards was to strengthen their resistance considerably. At first confined to Ulster, galloglas later spread throughout Ireland in the service of the great families. These mercenaries prolonged the life of the independent Gaelic kingdoms for more than two centuries after the defeat of Edward Bruce (14). Four centuries after the conquest, the O’Neills and O’Donnells were still ruling most of Ulster according to the customs of their ancestors. It was not until their defeat in the Nine Years War (15) in 1603 that all of Gaelic Ireland finally fell to the invaders.

During the seventeenth century, Irish military history was to a considerable extent an offshoot of events in England. The alliance between the Catholic Old English and the Gaelic Irish was to develop in the 1640s into a confrontation with the English parliamentary forces (16). When James II landed in Ireland in 1689 in a desperate bid to regain his throne, he was using the island as an outpost in an English struggle for supremacy between Stuart and Orange (17).

With the triumph of William of Orange and the emigration of many Irish soldiers throughout the last decade of the seventeenth century (17) and much of the eighteenth, any serious resistance was finally crushed. Ireland was totally subdued, and any future resistance was to take the form of rebellions of varying ineffectiveness. Despite the setbacks of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries when Ireland had looked to Spain, France and the papacy for help against England, the dissident elements of the Irish people continued to hope that ultimately foreign intervention would give them independence (10). During the sixteenth century, Ireland had become a country whose fortunes were of interest to Continental powers, and to some extent it became a pawn in the military and ideological conflicts of Europe. During the reign of Elizabeth, three invasions occurred in support of the Munster rebellion and the Nine Years War. The Continental confrontation between William of Orange and Louis XIV had its echo in Ireland, whither Louis sent men, arms, ammunition and money. He was concerned less to secure a decisive victory for James than to deflect William’s attention from the Continent by facing him with a long drawn-out war in Ireland.

After William’s victory there was no further Continental intervention in Ireland until after the French Revolution. The United Irishmen leaders, inspired by concepts of universal brotherhood and republican solidarity, managed to involve the French in the 1798 rising (19). This new defeat deterred the Continental powers from giving any further help, and during the nineteenth century Irish revolutionaries had to go it alone, their only foreign help being financial support from Irish-Americans (51).

In 1803 Robert Emmet led an abortive rising that in many ways was merely a continuation of that of 1798. Bad communications led to a confusion of orders, and when the rising eventually broke out on 23 July 1803, instead of involving 3,000 men as planned, Emmet was left with a rabble of only eighty. He and twenty-one others were executed.

Even more ineffective was the Young Irelanders’ rising in 1848 (31). They had made few preparations or plans for a rebellion, which was precipitated by an acceleration of government coercion and the arrest of many of their leaders. The main organizer was William Smith O’Brien, but no amount of rhetoric could persuade the starving Irish peasantry to reject the advice of their clergy and fight for intangible political ideals. The country scarcely noticed either the rebellion or the subsequent transportation to Van Diemen’s Land of its leaders, who included Smith O’Brien and Thomas Francis Meagher; even before the rebellion, John Mitchel had been transported there.

The other Irish rebellion of the nineteenth century owed something to that of 1848. A number of Young Irelanders – including James Stephens and Charles Kickham – were later to become Fenian leaders. Although their rising in 1867 (51) affected only a few scattered areas of the country, until independence the Fenian movement was to be a potent force in Irish revolutionary circles.

Irish revolutionary activity during the twentieth century again brought in a Continental element. The 1916 leaders (20) received help from Germany, and during the 1930s and 1940s IRA groups negotiated for German aid. As was the case with earlier Continental help, German aid was given with the object of harassing Britain rather than of helping the Irish. Over the past few decades, the IRA has received money, equipment or moral support from a variety of sources, including Libya, international terrorist groups and unofficial Irish-American sympathizers (51).

There is a coherent pattern in Irish military activity. Until the seventeenth century,when the woods were cut down and roads improved, military encounters were dominated by physical considerations (8) – problems of terrain. For almost four centuries there was a continuous struggle between invaders and defenders, which broadened during the late sixteenth century to involve Continental armies. During the seventeenth century, military activity was mainly a consequence of what was going on in English politics. From the eighteenth to the twentieth century militarism was restricted to no more than a tiny section of the population. Not until the Anglo-Irish war of 1919–21 did a significant minority become involved in any of the various armed rebellions, which until 1916 had little political impact (although an unintended consequence of the 1798 rebellion was the Act of Union). With the outbreak of the Civil War in 1922 there developed an ugly confrontation that would prove a divisive force in Ireland until the present day (34). Since the 1970s, the IRA, its offshoots and its loyalist paramilitary opponents have introduced a pattern of random violence and destruction into Irish military activity.

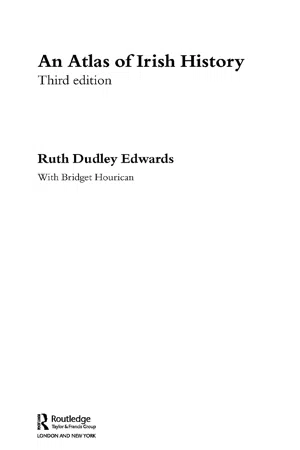

Figure 8 Strategic considerations.

8 STRATEGIC CONSIDERATIONS

Ireland’s natural barriers have always posed problems to invading forces. Only the Vikings, with their skilful command of rivers and lakes (11), were equipped to meet competently the physical hazards of the country. For other invaders, a country so liberally supplied with rivers, lakes, mountains, bogs, drumlins (small hills) and an inhospitable coastline posed almost insuperable difficulties. Additionally, until their commercial exploitation in the seventeenth century, vast areas of woodland covered the country, forming virtually impenetrable barriers to effective progress. In the early seventeenth century, about 15 per cent of the total area of the country was forested. Vast tracts of woodland made most of north-east Ulster and south-west Munster almost totally inaccessible, while extensive detours were necessary to reach many parts of Connacht.

Ulster posed the most serious problems of accessibility, and its physical defences explain why Gaelic rule continued throughout most of the province until 1603. There were only three entry routes. Two were close together in the south-west, where Ulster and Connacht are separated by the river Erne, one approach being over the river near Ballyshannon and another between the lakes at Enniskillen. In the south-east of Ulster there was the Moyry Pass, the gateway to Ulster known as the Gap of the North and said to have been defended by the mythological Cuchulainn. Moyry is the gorge in the hills between Dundalk and Newry through which the Slighe Mhidhluachra (61) ran, ‘where the Irish might skip but the English could not go’. From a military angle, the importance of commanding these vantage points was obvious: the earlier neglect of forts in Ulster had severely handicapped the English army in the Nine Years War (15).

In the west of Ireland, although it could be forded in a few places, the Shannon posed a formidable obstacle to an advancing army, and the country beyond was inhospitable and unfamiliar. Leinster was familiar territory, but even there, before the seventeenth century, the English were never at home in the mountainous and wooded areas of Wicklow from which the Irish chiefs launched frequent attacks on the Pale (28). From the military point of view, the most favourable part of Ireland was south-east Munster, which had rich land, numerous towns and good communications.

The Irish were successful in resistance while they used the Fabian tactics suitable to their difficult terrain. The Normans settled in good land, and while the Irish avoided direct confrontation and stuck to forays from their mountains, woods and bogs and used guerrilla tactics, they could hope to compensate to some extent for their inferior military skill and equipment. O’Neill was successful as long as he stayed in Ulster; it was only when he moved to Munster that he met defeat.

The English learned well the lesson taught them by O’Neill, and by 1610 a chain of garrisons and forts had been set up around the whole country. Twenty-six garrisons and thirty forts established government control throughout Ireland, and guarded trading towns and landing places from foreign invasion.

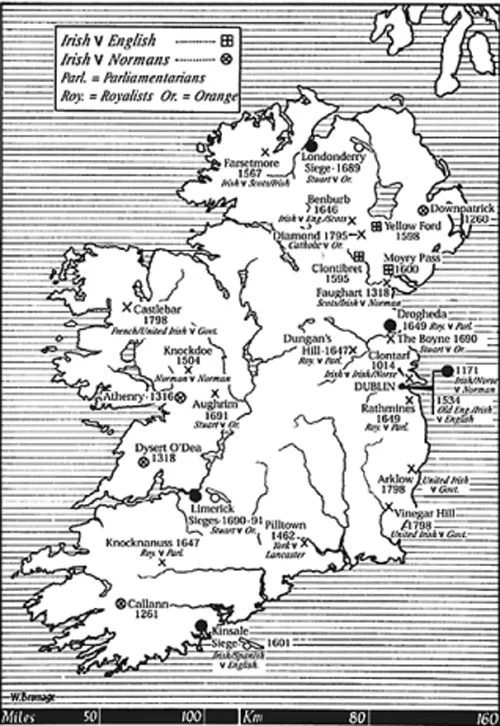

9 BATTLE SITES

Figure 9 is a reference point for the main battles or sieges in Irish history. So many different protagonists are found in Irish battles, including Irish, Norse, Normans, Old English, Scots, English, royalists, parliamentarians, Protestants and Catholics, and there is such a bewildering mixture of these elements, that it is impossible to convey more than a general indication of the main bodies on each side.

1014

Clontarf

Victory of the High King, Brian Ború, over his challenger, Máel Mórda, king of Leinster, the Norse of Dublin and Norse allies from Orkney, Scandinavia, Iceland and Normandy (11).

1171

Dublin

Strongbow and Dermot MacMurrough took Dublin in 1170, but in 1171 were threatened from the east by a fleet of 1,000 Norse under the displaced King of Dublin, Asgall, and from the west by a much larger army led by the High King, Rory O’Connor. Instead of launching a united attack, the Norse attacked in May and were decisively defeated by the Normans. The High King continued to build up his forces and besiege Dublin, but in September a surprise raid on his camp by a small Norman army resulted in a complete rout (12).

1260

Downpatrick

As part of the attempt to revive the O’Neill claim to the high kingship, Brian O’Neill of Tirowen led an attack on Norman settlers in Down, and was defeated (13).

1261

Callann

In 1259, a royal grant of Desmond and Decies was made to John FitzThomas. This provoked a rising of the MacCarthys, who at the battle of Callann won a total victory over FitzThomas and the justiciar, and confirmed for a time their control of south-west Ireland (27).

1316

Athenry

On 10 August, the Anglo-Irish of Connacht, under William de Burgh and Richard de Bermingham, crushed a huge Gaelic army, killed over sixty chieftains and ensured Norman supremacy over Connacht (14).

1318

Dysert O’Dea

Contemporaneous with the Bruce invasion were the last stages in the war in Thomond between the native rulers, the O’Briens, and the Norman settlers, the de Clares. In May 1318 came the final confrontation, with a total victory for the O’Briens and a recovery of their kingship, which in 1540 became an earldom (14).

Faughart

Total defeat of Edward Bruce and an army of Scots, native Irish and Norman rebels by a Norman force led by John de Bermingham (14).

1462

Pilltown

Ireland was very largely Yorkist in sympathy during the Wars of the Roses, giving support to Richard, duke of York, when he fled from England. The only notable Lancastrian supporters were the Butlers, whose attempt to prolong the struggle led to their defeat at Pilltown in 1462 by a force led by Thomas, earl of Desmond, and their subsequent exile (27).

1504

Knockdoe

In August 1504 was fought the battle of Knockdoe between the Lord Deputy, the Great Earl of Kildare, and his son-in-law, Ulick Burke of Clanrickard, ostensibly because Burke was challenging the royal authority in Galway, but really because his increasing power was becoming a threat to the Kildare balance of power; Kildare was not prepared to countenance any rival. Kildare’s army consisted of his own men (including galloglas) and the forces of his Ulster allies – including O’Neill, O’Donnell, Magennis, MacMahon, O’Hanlon, O’Reilly; of MacDermott, O’Farrell, O’Kelly and the Mayo Burkes from Connacht. He also had the support of the great Pale families, including the Prestons, St Laurences and Plunketts (27). To set against this force, Ulick Burke had the support of the O’Briens of Thomond, the Macnamaras, the O’Carrolls and the O’Kennedys, and his own force of galloglas. The precise numbers cannot be estimated, but they were substantial, with the Great Earl having a numerical advantage and using firearms for the first time in an Irish battle. Kildare’s victory was total, and smashed the power of the south-east Connacht/ north-west Munster alliance.

1534

Dublin

In February 1534, Kildare was summoned to London and imprisoned in the Tower; his son and deputy, Thomas, Lord Offaly, known as Silken Thomas, on hearing a rumour of his death, led an unsuccessful rebellion in Dublin in which the archbishop of Dublin was killed. Although Offaly took the city he was unable to take Dublin Castle. Under Sir William Skeffington, the new lord deputy, a large army arrived which suppressed the rebellion and in March 1535 took Offaly’s Maynooth stronghold by the use of heavy cannon (27).

1567

Farsetmore

Shane O’Neill’s attempts at territorial aggrandizement in Ulster continued until 1567, when they were ended by the battle of Farsetmore, brought about by his unsuccessful attack on the O’Donnells. The O’Donnells relied mainly on galloglas, while O’Neill had a force that largely comprised his own people, whom he had militarized over the years to compensate for the shortage of mercenaries (54).

1595

Clontibret

In May 1595, Marshal Sir Henry Bagenal set out to relieve the English outpost of Monaghan, under attack from Hugh O’Neill. He marched with 1,750 men to Monaghan, suffering some harassment on the way. While returning, he encountered several ambushes, culminating in a battle at Clontibret where severe losses were sustained. Only a relief force from Newry...