![]()

1

CROSSING THE THRESHOLD

Although a significant number of music educators internationally have had a fairly difficult run in the late stages of the twentieth century and the early years of this new one due to decreasing support for music in schools, many have bravely attempted to find ways to offer music programmes in which music’s wonderful diversity can be introduced. This may involve musical traditions around the globe, various forms of popular and art music as well as more recent forms of musical experimentalism. This volume is intended to help those interested in sharing the excitement and joy of making music with sounds as part of this broad curriculum. Although one might consider sound-based music to be of fairly marginal importance, the fact is that it is rather ubiquitous in today’s world. It can be found in a variety of audio only and audio-visual forms including films, advertisements, computer games and a wide variety of compositional approaches.

This book’s point of departure is to allow teachers and students to maximise their own creativity, as was the case in my 1994 book, Experimental Music Notebooks (Landy 1994a). In Making Music with Sounds, given its emphasis on technology, the idea is that teachers are invited to adapt activities to local circumstances. In other words, without a great deal of equipment and software, it is still possible to reach a high level of creativity in the book’s areas of focus. Some educators might prefer a list, similar to a manual, of carefully worked-out examples. This formula has been rejected for a number of reasons, the most important of which is that this kind of music is rarely produced in this manner. Furthermore, many formulaic educational publications are written for a particular group with particular skills in a particular place or, alternatively, expecting only some of their examples to be useful to any given group. In contrast, this book’s underlying philosophy is that it is more important to facilitate creativity than to prescribe it.

In this manner, the book can be seen to act as a source of inspiration as well as a basis for teaching, allowing the EARS II online resource to pick up where the book leaves off, as it were. It is worthy to note that virtually no specific hardware or software is mentioned throughout, as these things seem to get dated, thus placing a time stamp on the book. Instead, more generic terms will be used, e.g., sampling* instead of naming a hardware or software sampler. After this introduction, which will include a survey of types of music related to the book’s focus, the structure of the following chapters is one moving forward progressively commencing with an awareness of our aural environments, whether rural or urban or anything in between. In so doing, the notion of different types of listening, also known as listening strategies, will be introduced. The soundscape*, the aural equivalent of a landscape, will act as the second chapter’s focus in terms of sound organisation. Chapter 3 takes us to the level of the sound unit. It will be proposed that any sound can be made musical. The chapter will discuss how to “grab” a sound for artistic use, how to generate one from scratch and how to manipulate sounds. The content of Chapters 4 and 5 takes us beyond that of the sound level. Their focus increases to the sequence or gestural level and then to that of an entire piece. The chapters include sections on vertical and horizontal relationships regarding sound organisation (in traditional terms, think of harmony and counterpoint) and both include important sections concerning evaluating one’s work. It is never easy to say what is good or bad, what is powerful or weak, but avoiding this kind of discussion is not very helpful. The volume does not have the pretension to suggest that it is presenting a new vision regarding the aesthetics for sound-based music; what it does do is allow groups of people to discuss what individuals or groups have come up with and then to see whether the results are representing the maker’s intention. Special subjects include the notion of “breathing” in sound-based music and how rhythm fits into music in which pitch and harmony are not necessarily important. The final chapter summarises the key aspects that have been presented and suggests further challenges for those who have developed an interest in sound organisation, such as (online) group performance. The book concludes with a glossary and a bibliography that includes an annotated section for further reading.

Before commencing this incremental presentation, the rest of this introductory chapter will focus on the delineation of the two areas that we will be involved with: sound-based music and making music with technology. A brief description of the approach including the role of the book’s flexible activities follows before the introduction’s concluding survey is presented.

A Delineation of the Two Key Areas

This text will focus on two key areas, although not exclusively. To speak of sound-based music without acknowledging its much older partner, the music of notes, would be ridiculous. Similarly, to discuss music that uses technology without allowing acoustic creativity to take place is equally absurd. Nonetheless, the two key areas are the reason for this book’s existence. Let’s briefly attempt to draw a virtual fence around these foci.

Sound-Based Music

A few years ago while preparing another book, Understanding the Art of Sound Organization (Landy 2007a), a problem was highlighted to specialists, namely the less-than-satisfactory state of the field’s terminology. I was particularly aware of this, as one of my main projects in the years preceding the writing of that book was the creation of the glossary section of the EARS site. I was faced with the dilemma of attempting to make a choice among a number of existent ambiguous terms for the music that I make and wanted to discuss. After a great deal of consideration I decided to create a new, unambiguous term, sound-based music defined in the preface, and this is the one that will be used here. Let’s start with this term and a few of the other ones as readers may confront them in other literature that they may consult.

Admittedly all notes are indeed sounds, so some people in the field have claimed that sound-based music taken literally is a synonym for music. However, the purpose of Understanding the Art of Sound Organization was to introduce the co-existence of a note-based as well as a sound-based musical paradigm and demonstrate that, although these two clearly overlapped with one another, they were highly distinct as well, both in terms of aspects related to musical construction and reception.

Terms that were also in contention included:

• Sonic art*, which could be defined in the same manner. The issue with this term is that it allows people to consider its works not to be music, something that I find problematic. There are even universities today that have departments that are named Music and Sonic Art. People cannot even agree whether the term takes on the singular or plural form, sonic arts.

• Electroacoustic music*, which many specialists would assume to be synonymous with sound-based music; however, there exist electroacoustic works that are in fact focused on notes; furthermore, electroacoustic music cannot be solely acoustic.

• Similarly electronic music* might be seen to be synonymous by some people, particularly in the United States; however, most people view this term to refer to music in which sounds are generated synthetically.

• Two other rejected terms were sound art* (too specific) and

• Computer music* (too broad).

• Even the older term, organised sound* (also the title of a journal that I edit), did not seem appropriate for the same reason that sonic art(s) was rejected. Furthermore, the composer who originally coined the term, Edgard Varèse, as visionary as he was, was thinking of all sounds including notes; the term also does not really sound like a musical category.

• Another historical term, musique concrète* (literally concrete music, but the French term is normally used) is worthy of mention. In the early days of sound-based music, some musicians focused on synthetically generated sounds, thus making electronic music. Others, following the lead of Pierre Schaeffer, made musique concrète. This music was largely based on recordable sounds, although synthetically generated ones were not explicitly forbidden. The term is now dated, but its works fully belong within sound-based music.

Having chosen among those terms, there remains one controversial point to be shared: one person might reject what another person hears as music. Suffice to say that there are many who do not consider most pop music to be music, something most readers might find lamentable. I have known of individuals who do not consider African drumming to be music, as it possesses no audible melody.

Whatever one calls this creative work that we shall be discussing, many perceive it to be music, and it is due to this conviction that sonic art had to be rejected. Still, people who encounter a subset of sonic art known as sound art, that is works often displayed in art venues or public spaces sometimes in the form of installations, may have difficulty with this view. My reaction to this is that there are art works that fit into more than one medium and sound installations* represent a typical case in point: they fit within three-dimensional art as does sculpture and they also fit within music. To conclude this part of the discussion, I propose that organised sounds are music in the ears of the beholder and hope that readers and their students will join me in beholding such works as sound-based works of music too.

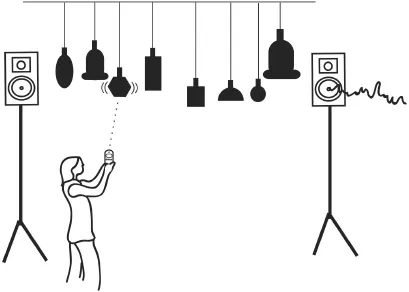

FIGURE 1.1 A sound installation

Making Music with Technology

How often have you read about the impact of new technologies in our daily life? Of course, music forms no exception. All one needs to do is consider how music was heard just over one hundred years ago—you had to be there. Now compare that with the current situation—music is heard mainly by way of technology.

We have to be careful, for without technology, the violin bow, just to name something at random, could never have been made. We are of course referring to technologies here that are driven by electricity or similar form of power, and mainly new forms of digital technology.

Such technologies have allowed us to record and re-record sounds by way of multi-tracking, also known as overdubbing. Of course, re-recording is relevant to traditional forms of music as well as to what we are to discuss. They have also allowed for sounds to be manipulated, sometimes to the point where their source can no longer be recognised. Furthermore, using these technologies, we can make or generate new sounds from scratch. It is the art of applying such technologies to make music using sounds that is at the heart of our journey.

Still, such technology is not necessary to make music with sounds. Those stones and glasses could make either note-based or sound-based music depending on the approach by those playing them. Therefore we need not be obsessive about technology for technology’s sake, but instead look to use it for specific purposes. Today’s technology serves all of the above purposes and many more. Of these, several will be introduced in the remaining chapters.

Before moving on, some readers may be unaware of the fact that a number of practices today have been responsible for the redefinition of aspects related to composition and performance. In a sense some traditional practices are being recycled or renewed. For example, as in traditional societies, a significant number of sound-based pieces are composed collectively, that is, without the need to name a composer as one does traditionally. The performance is the work of all involved. Improvisation is also something commonly practised within sound-based music. This raises interesting questions related to the act of composition.

For example, in today’s remix culture, the re-use of sound material does not necessarily mean that the musicians involved are interpreting those materials. They are re-composing them. But who is the author of a piece of “appropriated” sounds? In short, some may still practise the trade of composer, performer or improviser. In sound-based music all of these are possible, but increasingly for many musicians, composing, improvising and remixing are three forms of creating. As much of this can be done in real time, that is, on stage, composition, improvisation and performance can be one and the same in such cases. With this in mind, what one does with the approaches that are introduced below is as diverse as the musicians’ imaginations. As stated in the Preface, this book will focus on composition prior to performance given the number of concepts that will be introduced.

The Book’s Approach

As suggested above a non-time-stamped approach has been chosen where one will speak of sampling instead of any particular sampler and so on. Furthermore, as stated, the amount of resources is not being imposed; therefore people with modest resources will be able to achieve a great deal of what is proposed in this volume. Just to offer one example, there are two ways to “hunt” for specific sounds: find them and record them or, if that option is not available, attempt to download them from sites that offer sounds such as the well-known Freesound Project (www.freesound.org). There are no ivory tower approaches here nor am I seeking to reach the lowest common denominator, as it were. It is with this in mind that the only assumption is that people taking part in activities in the following chapters have access to a computer, speakers attached to that computer and an Internet connection. For those users who possess more than this, options, for example the use of a microphone and something on which to make recordings as just mentioned, will be presented alongside the basic way of doing things.

Every group in schools has a different level, a different dynamic and different means to achieve things. It is for this reason that the book’s activities seek to enhance creative thinking and creativity in terms of skills acquisition as opposed to learning specific skills in specific ways, as this is simply impossible to generalise. I have done a great deal of work in what is known as the community arts. It is awful to work with people with top-of-the-line equipment and to leave with that equipment. People are offered a great ride in a Bentley and are left afterwards with whatever they had previously. It is much better to provide exciting experiences with what people possess already. We all know there’s bigger and better out there if we are offered the means to improve our situations.

In Experimental Music Notebooks I included the remark (paraphrasing the artist Josef Albers): “Our approach calls for the creation of musical problems and trying things out. Experimentation is based on trial and error—a healthy phenomenon and a wonderful way of discovering creative processes. [Music appreciation and active music making] are essential for a more complete musical experience, especially when combined with the individual’s imagination” (Landy 1994a, 12). That point of view worked then and remains the basis for the current, more focused book.

To conclude this part of the introduction related to the book’s approach I have to admit that I find that those who make computer games have come up with an excellent formula for most users that can be applied in this book’s educational context. Set new challenges at every level of a given game, as the player will be keen to learn (read: overcome the challenge), gain the new skill and climb to the higher level. Most of the challenges proposed in the following chapters can be stepped up, just like a computer game, depending on the time, abilities and facilities available. The activities are flexible and thus dynamic in this way. Another thing implicit in computer games is that they are to be enjoyed (although many players work very hard to achieve that enjoyment); similarly, art making is about enjoyment. If we turn this enjoyment into just work, our students or we may lose interest. Therefore applying such aspects related to computer games can lead to a valuable educational approach. The chapters and challenges posed are based on this very combination of learning and enjoyment. I hope that this works for you and, where relevant, your students.

An Overview of Selected Genres and Categories Related to Sound-Based Music

This chapter concludes with an overview of types of music that are associated with sound-based music; one might call it a supergenre or genre of genres. This overview will commence with the difference between music using real-world sounds and generating material by way of sound synthesis*. Furthermore, some key historical points will be touched on briefly as they should also be of interest to many readers. Sound examples of all of the following types of sound-based music can be found on EARS II. It is by no means necessary to include all of the following in a given curriculum; this final section of Chapter 1 is inten...