This is a test

- 308 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book reveals how an empire that stretched from Glasgow to Aswan in Egypt could be ruled from a single city and still survive more than a thousand years. The Government of the Roman Empire is the only sourcebook to concentrate on the administration of the empire, using the evidence of contemporary writers and historians.

Specifically designed for students, with extensive cross-referencing, bibliographies and introductions and explanations for each item, this new edition brings the book right up-to-date, and makes it the ideal resource for students of the subject.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Government of the Roman Empire by Dr Barbara Levick, Barbara Levick in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

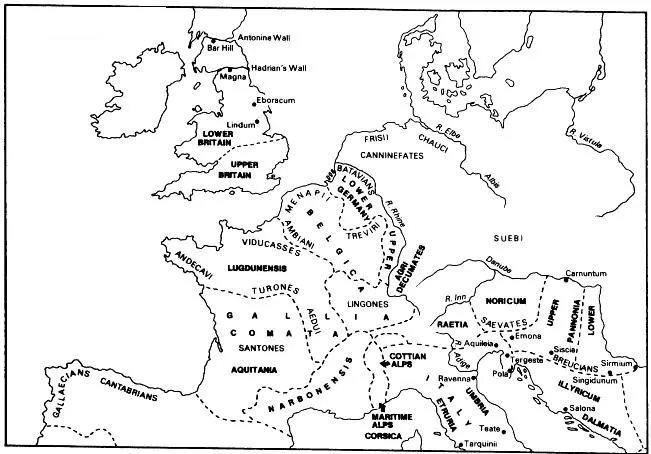

Map 1 Italy and the Western

Provices

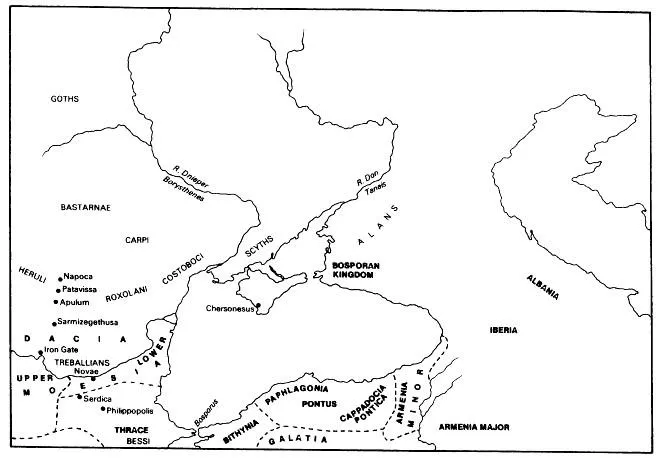

Map 2 The Eastern Provinces

Map 3 Gaul

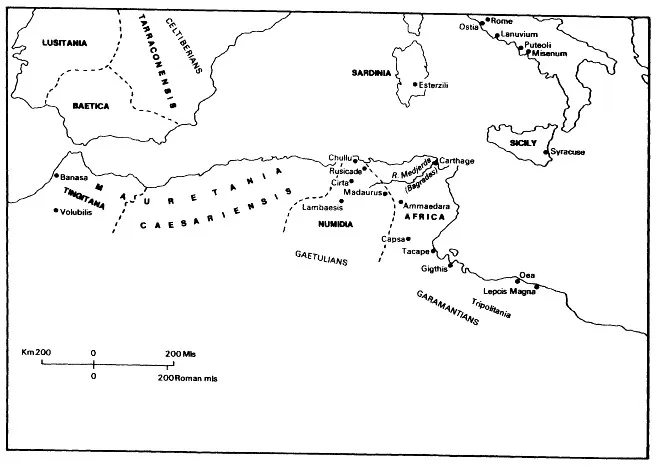

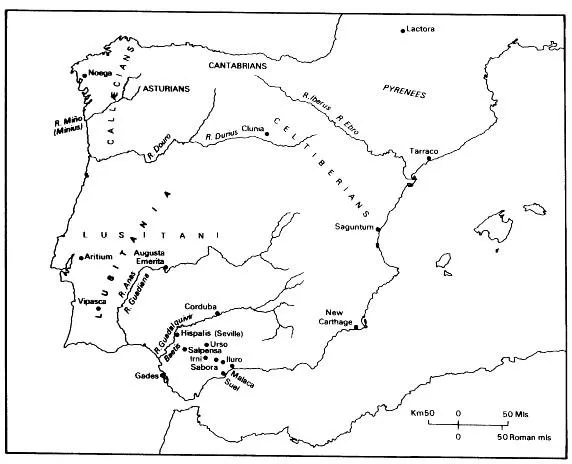

Map 4 Spain

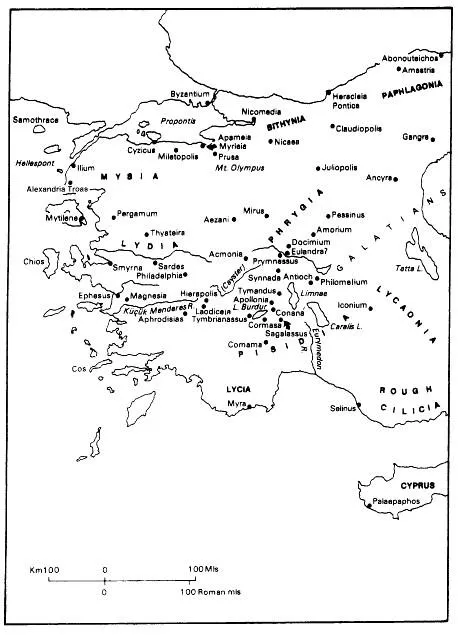

Map 5 Western Asia

Minor

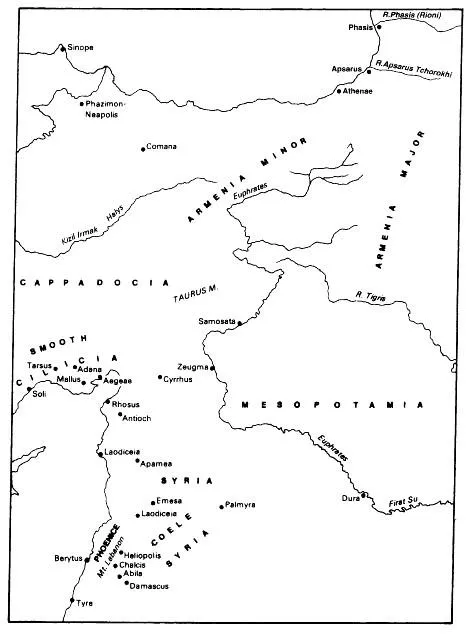

Map 6 Easter Asia Minor and the Levant

1

INTRODUCTION: THE POWER OF ROME

The power of Rome, imperium Romanum, lasted from the traditional foundation date of the city in 753 BC until AD 476, the conventional date of its end in the west, and until the fall of Constantinople to the Turks in AD 1453 in the east. The documents in this book show the Empire at its greatest extent, and at its most confident, during the three centuries from the permanent establishment of one-man rule in 27 BC to the onset of acute problems, military, political and economic, in the third century AD. The establishment of the Principate at the end of the Civil Wars of 49–30 made it possible to adapt existing institutions to the needs of the Empire and to set up new ones, and it was able to emerge through another period of reform and renewal into the fourth century.

Repugnant though many of its features are (the rigid class structure, slaves at the bottom of the heap), the Empire commands respect for its durability and for the effect its existence has had on the language, literature, architecture and law of Europe and elsewhere; it is worth asking how it survived so long. Some answers may be found by examining the machinery devised by the Romans for controlling the Empire (Chapters 2–4); more by considering changing attitudes towards Rome’s subjects and the way some of them came to feel about Rome (Chapters 7–9).

In itself, the machinery of government looks grossly inadequate even if we allow for the diplomacy that exploited inter-tribal and intercity hostility and remember that the tribes were badly placed to organise a durable resistance, while much of the eastern half of the Empire had long been under alien rule. From Hadrian’s Wall in the north to Leuce Acra on the Red Sea was 4,654 km (2,890 miles), and the population of the Empire has been estimated at between fifty and sixty million. Yet the army that kept it was only thirty legions strong in the later second century, about 150,000–180,000 men, with a force of about 253,690 auxiliary troops and sailors (Birley in King and Henig 1981(12), 40ff.; for lower estimates see Mitchell 1983 (6), 147 n.14) and the members of the Roman upper class (members of the senate and of the equestrian order, the ‘Knights’, that ranked immediately below it) actively involved in its administration at any one time has been put as low as 150 (Hopkins 1980 (5), 121). True, the respect that the army inspired in enemies and subjects was enhanced by strategic positioning of the troops (the Rhine legions more than once showed that they were as well placed to deal with revolt in Gaul as with German tribes (201), and those in Syria kept as much of an eye on the inhabitants of Antioch and Laodiceia as they did on the Parthians beyond the Euphrates (cf. 42) and by their mobility. As the army settled to a relatively static role, the legions moving towards the hardening periphery of the Empire (Luttwak 1976 (3) 55ff.), the habit of obedience prevailed among Rome’s subjects (with notorious exceptions, such as the Jews in Judaea (204f.)).

Whether this apparent inadequacy is something that needs explanation or whether it rather helps to explain Roman success (as Dr Nash has suggested to me), in that only such economy of means made expansion and the maintenance of the Empire possible, there is no doubt that expansion was intended to pay, in booty, land for settlement and leasing out, and taxation. That was made clear when Italy was exempted from the payment of direct taxation in 167 BC. Not only the state was to benefit: the careers and reputation of individuals depended largely on military glory and they were often readier to take decisive and aggressive military action than the senate as a whole (hence divergent views as to the nature, offensive or defensive, of Roman wars under the Republic and the way Rome came by her Empire); the minimum cost of wars in money and manpower was calculable, while the outcome was uncertain and the profitability of acquisitions variable. Calculations were made about it, even if only after a decision had been taken, probably on quite other grounds; as it had about Britain before Strabo wrote, justifying it.

1. Strabo, Geography, 4, 5, 3, p. 200f.; Greek

At the present time, however, some of the chieftains there, who have sent embassies to make overtures to Caesar Augustus and have secured his friendship, have set up offerings on the Capitol and have made the island virtually a Roman possession in its entirety. They are also so ready to put up with heavy duties on what is imported into Gaul from there and on exports from here … that there is no need for a garrison on the island. It would require at least one legion and some cavalry to take tribute off them, and the expenditure on the troops would equal the sums they contributed: (p.201) the customs duties would have to be lowered if tribute were imposed on them, besides which there would be a certain amount of danger involved in using force.

Profits fell after the Republican era: less territory was acquired and the pickings were less rich (Dacia with its gold is an exception); what had already been acquired had to be garrisoned at a high cost in money and men. Even with extensive use of non-citizen troops, it put a strain on imperial finances (83) and Italian manpower (31).

By the time the Principate had stood for nearly two centuries, a Greek-speaking native of Alexandria, though one involved in Roman government, could write of the Empire almost in ‘white man’s burden’ terms.

2. Appian, Roman History, Preface, 7

And with these imperatores or emperors it is very nearly two hundred years more [beyond the five hundred it took to establish Roman power in Italy] to the present time. During this period the City has been very greatly beautified and revenue has been increased to a very great degree, and in the course of long-standing and steady peace everything has progressed towards secure prosperity. And these emperors have annexed to the Empire some peoples besides the earlier ones, and others that have revolted they have brought under control. Possessing the best of land and sea, they wish on the whole to preserve it by prudence rather than extend the Empire indefinitely among wild tribes who are poverty-stricken and unprofitable. I have seen some of them at embassies in Rome offering to give themselves up as subjects, and the Emperor rejecting men who would not prove of any use to him. To other peoples, innumerable ones, they themselves assign kings, if they want nothing of them for the purposes of the Roman government. And on some of their subjects they actually spend money: they are ashamed to exclude them even though they are expensive. They have large armies stationed all round the Empire, and keep guard over the whole, land and sea, huge as it is, as if it were a small district.

Appian, writing under the Antonines, has adopted the doctrine that became conventional after Trajan’s war with Parthia had failed (117) and Hadrian had called a halt to eastern conquests: the Roman Empire was as big as it should be, and needed only to be kep...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Dedication

- Acknowledgements

- List of Abbreviations

- Weights, Measures, Currency and Wealth

- Maps 1-6

- 1 Introduction: the Power of Rome

- 2 Structure

- 3 Force

- 4 Law

- 5 Financing

- 6 Communications, Transport and Supplies

- 7 Loyalty: the Role of the Emperor

- 8 Patronage

- 9 Assimilation

- 10 Failings

- 11 Resistance

- 12 Crisis?

- Chronological List of Emperors

- Select Bibliography

- Index of Passages Cited

- Index and List of Ancient and Modern Geographical Equivalents