- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

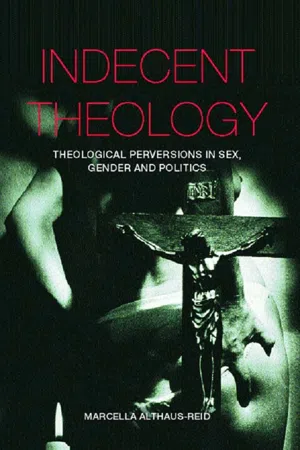

Indecent Theology

About this book

Indecent Theology brings liberation theology up to date by introducing the radical critical approaches of gender, postcolonial, and queer theory. Grounded in actual examples from Latin America, Marcella Althaus-Reid's highly provocative, but immaculately researched book reworks three distinct areas of theology - sexual, political and systematic. It exposes the connections between theology, sexuality and politics, whilst initiating a dramatic sexual rereading of systematic theology.

Groundbreaking, intriguing and scholarly, Indecent Theology broadens the debate on sexuality and theology as never before.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Indecent proposals for women who would like to do theology without using underwear

DOI: 10.4324/9780203468951-2

The collapse of the Grand Narratives of Latin America: theology and sexual mutilations

The Grand Narratives, or the authoritative discourses which sustain everyday life, which Gramsci spoke of when writing about the common sense or common order of things which are ideologically constructed yet have assumed a natural and almost biological presence in our life (Gramsci 1971: 33), collapsed in Latin America over the course of a few years. Cultural, religious, socio-political discourses, economy and science, and philosophical cosmovisions which defined identity, meaning and patterns of social organisation and sexual constructions were obliterated from the earth. Even language was erased. Tongues’ were lost; mother tongues were buried while human tongues were cut from mouths. Women’s tongues were silenced for centuries. What survived entered into a covenant of silence, and since then it has never fully spoken again. Following Jacques Lacan, we may say that it was a silence of the magnitude of planets, silenced as if by a set of Newtonian laws, replaced by unified field theory and leaving behind anything outside the new cosmovision. ‘We will never know what can happen to a reality till the moment that this reality has been definitively reduced by inscribing it in a language’ (Lacan, in Miller 1990: 357–60). Unified field theories resolve perplexity, avoid relationalism and install laws assigned to points of space or space-time as particulars. Precisely, the resolution of perplexity (plurality) in Latin America was done in material ways. ‘From some people the buttocks were cut, to others the thighs, or the arms … cutting hands, noses, tongues and other pieces from the body, eaten alive by animals and (cutting) women’s breasts’ (Todorov 1987: 151). These mutilation rituals, paraphrasing Lacan, could be compared to the cutting off of the breasts of truth, the reductionism into a new bodily order, that is, humanity reduced to one formula, one law of union and compulsion. This required a massive mutilation. The need for Grand Narratives always takes with it some cuttings and mutilations in itself. Latin American theology comes from that, a mutilation of symbolic knowledge such as theology, politics, economics, science and sexuality It was the time of enforced martial law on perplexity, but not an end of authoritative discourse followed by deconstruction. A deconstructive path would have submitted responses ‘to endless interrogations … overthrowing power, to preserve the opening’ as Jabès says (Harvey 1986: 94). We have nothing to fear in deconstruction if this process carries with itself a problematisation of reality which opens to new questionings and visions. Instead of that, what happened after the Conquista was an authoritarian process, and the imposition of the Great European Meta-narratives on people’s lives. That was more a process of asset-stripping than deconstruction. The Latin American Grand Narratives became redundant, empty (in Spanish the name given to asset-stripping is vaciamiento, emptying) perhaps due to the fact that every Grand Narrative carries in itself an objectification of a Lebenswelt or ‘World of Life’. Let us consider this point in detail. The production of Grand Narratives is in itself a way of commodifying life. These are no innocent paper moons. These are concrete intentional discourses growing from relations of production and capital appropriation. The end of the Grand Narratives of the Original Nations was an undressing process, and the native’s new nakedness was then available to be re-dressed with a different (European) Grand Narrative, yet one which fulfilled the same objective as the first. Therefore, I am not claiming that the Grand Narratives of the Original Nations were better or worse than the European. No, I am only saying that the natural processes of deconstruction never happened and people were brutalised into Christian Grand Narratives and economic discourses by criminal forces. Narratives of people’s exploitation and women’s submission in Latin America did not change, at least not substantially. Only the masters who gave names to the planets, still following Lacan, and determined their reduced vocabulary, changed. A more brutal regime and a genocide without magnitude happened in the continent, but as a woman I cannot say that the situation of women after the Conquista was substantially different from before. However, as I will argue later, deconstruction is unavoidable even if forcefully obstructed. Deconstruction can be traced in Latin America in multiple forms of political, cultural and religious mistrust throughout centuries. The sexual mutilation still needs to be theologically addressed.

Lemon vendors who do not use underwear are indecent. The Argentinian theologian without underwear writes Indecent Theology. They both challenge in different ways the creation of a factual sexual order of things, one that became entangled in an alliance of patriarchy between Europeans and natives. Heterosexual Christian imaginary came to Latin America to reproduce expressive models of sex/gender by normalisation and control (Butler 1990: 24). These things are the bases of structural organisation in my country, the primal forms of normalisation and frontier patrolling systems as we know them historically. Indeed, the fact that we have been able to trace different political and cultural systems throughout human history but never a historical experience of non-heterosexual normalisation is significant, even if we take into account cultures where heterosexuality was constructed in different ways to the contemporary form with which we are familiar. Some understanding of heterosexuality is always in the origin of patriarchy. It is an understanding based on hierarchy and submission by processes of affirmation by subtraction: I am what I am not (a woman and not a man; a bisexual and not a ‘woman’); and what gets subtracted is also annulled: I am what I am not, a ‘woman’, therefore I am not. Heterosexuality is not a neutral science and the inner logic of the system works with its own artificially created ‘either/or’ concepts. It unifies the ambivalence of life into one official version. Per/versions (the different versions of a road) are silenced.

When Cortes met Moctezuma in 1519, the Grand Narratives behind these two men were based on two cosmovisions which set them apart except for one thing which they held in common: the patriarchal excess of their narratives of authority. From a materialist analysis, we can think about Grand Narratives as the surplus of praxis of patriarchal power, the matrix of which is constituted by heterosexual thought. Heterosexual power therefore continues, and provides the flow between Grand Narratives linked by occasional asset-stripping processes as we have already considered. For instance, the colonisers stripped Africa of its culture, religious and economic systems but kept patriarchal power intact, if not reinforced, by Christianity. Ricoeur, in his analysis of living metaphors, has considered how symbolic constructions develop a quasi-biological life. They are born, they develop and flourish, they form alliances with other symbolic systems, and finally die and/or transmute (Ricoeur 1967: 17ff). Grand Narratives also seem to follow similar processes, except that the primal binary construction of sexual systems remains alive (although not uncontested) and is reproduced into epistemologies and structures of political and social organisation. It is especially reproduced in our understanding of authority.

Authority defines authority, begets authority and resurrects authority. Authority is always positioned authority, Darwinian (surviving by force and confrontation) and self-perpetuating. We might be referring here to Western theological authority or USA capitalism. The authority of, for instance, the Grand Narratives of Christianity in Latin America is composed of these plus the following elements:

- A modern conception of (Western) linear time.

- A core knowledge base provided by the construction of the Western subject as constitutive of the real. Against that real, we position our invented lives.

The trajectory of Grand Narratives seems to follow a Western linearity and modern conception of progress, because progression also implies the notion of a point of departure, a constitutive moment, and therefore a regression, even if it is a regression to the not known or acknowledged, already there although occult. This occultist call is no doubt meaningful. Paraphrasing Chairman Mao saying that ‘good ideas do not fall from heaven’ (Lin Piao 1967: 206), we may say also that neither do Grand Narratives fall from heaven, but obey corporal needs of what Foucault called the disciplining and ordering of rationality, institutions and sexuality (Foucault 1980: 196–7), and we may add – of capital. We believe in them because they make us; we know we perish with them, too. However, the regressions of authority do not need to obey linear movements but can be digressions: for instance, sexual digression. If we do not have a point in our Latin American history to say that the sexual organisation of the continent was not heterosexual, we do have digressions, discordances and incongruences at any time. If North Atlantic visions of poor Latin America have been seen through heterosexual eyes, it is because the socially disadvantaged in the continent present different parameters of sexual transgression than in Europe or in the United States (Foster 1997: 7). The homosexuality amongst the Caribs and the sexual freedom of women in some indigenous communities may be erased from the theological history of our ancestors, but is strangely present in the sexual protest of the 1990s in Latin America, when people tired of militarism and repression have decided to come out as free people (Foster 1997: 13). Let us reflect, for instance, on the Maya conception of time, taking the Mayan subject as that which gives us this sense of preservation of the opening in understanding processes, which is so needed if one wants to avoid the ruling of progressive (linear) philosophical discourses (Derrida 1972: 211).

Maya theology is born of numbers and repetitions. The politico-religious Grand Narrative of the Mayas was built from the obsessive behaviour of controlling numbers, dates, astronomical calculus and construction. Each stone of a monument is part of a liturgical memory of numbers, which are important recorded human gestures in themselves. Their god was not the name of in/difference, but the numerical difference which approximated them to God. León-Portilla explains the cyclic but non-repetitive conception of time. The sol (sun) never rests. The appearance shows us that the sol is devoured in the chi-kin (the evening; literally, the sun in the mouth) but it penetrates the inner world (mundo interior), goes traverses and triumphantly, is born again’ (León-Portilla 1986: 34). Every sol comes with its Grand Narrative of origins and ordering but it is expected to die a death by penetration (their time pre-fixed, divined in the sacred texts) and resurrected by penetration too. Like the biblical genealogies of male descendants, one penetration giving birth to someone else till God enters into the genealogy by penetrating a woman’s womb. That is Jesus, part of a linear and progressive conception; yet resurrection adds circularity to penetration. Jesus’ death is an example of tolerance, of the enduring of human life. However, the sol’s death carries in itself the idea of some form of tolerance too. In other words, former identities were allowed to remain in the new sol, as a token of co-operation from the new discourse in power. The Aztecs are exemplary of that. They had confederate narratives, at least during the fifteenth century and the time of the Conquista. These reflected their tributary system organised around thirty-eight tributary provinces depending on Mexico-Tenochtitlan as a centre (Perez Herrero 1992: 43). The Triple Alliance of the Aztecs did not kill but incorporated regional identities and their regional discourses of identity. That was not what the Narratives of the Spaniards were about in their construction of authority: they brought Christianity without resurrection, without the tolerance of life. Theirs was a linear, terminal conception of Christian narratives. While the Aztec Confederation expected that at least some of their philosophical and scientific paradigms would be able to rotate as peripheral moons of the Spaniards’ Christianity, the Spaniards only wanted to kill them.

How did this religious philosophy of identity affect their sexual discourse? We know that women in the Aztec Empire were of low value and ill-treated. Were the alloying identity myths suspended in relation to women? Did women have a national and religious identity or a reflective one, that is, one that reflected their gender roles and positions? We will never know for sure, because much was destroyed and little was preserved in terms of books or accounts of the times before the Conquista. However, since we know that one of the factors in the fall of the Grand Narratives of the Original Nations was a different conception of time and the understanding of cycles of discourses of power, one wonders how they worked sexually. In short, what was the difference? There is a second factor to consider, and it comes from the fact that the Aztecs had a military narrative, which was the same as the Spaniards. The people were indoctrinated to obey and accept subjugation. It was part of the order of worship. Therefore, the fall of the Aztec Empire was a gravitational one; vertical military structures, tied to each other, collapsed without knowing how to find the space of the horizontal decisions and challenges. The military culture, patriarchy at its peak, erased the cyclical conceptions and understandings of God, also based on different compulsions on the side of Christians and Aztec: one group obsessed by numbers and metaphors of cyclical penetration; the other by a linear penetration pattern interrupted by Christ’s resurrection. In the end, the Aztec Confederacy’s Grand Narrative fell, perhaps because Grand Narratives have a set time for their own self-destruction. That ‘progressive erosion’ which Derrida identified in metaphors such as value of usury and usage (Derrida 1989: 39) is present also in Meta-narratives. The usury (usure) is that surplus of value which is transmitted in Aztec discursive confederations, which comes from the corporeality (Leiblichkeit) of the oppressed which through their oppression has given value to the Meta-narratives which objectivised them in the first place (Dussel 1988: 63). The usury, interest, continues and makes alliances and arrangements with new authoritative orderings. The story of colonial settlements and imperial control is a story of one basic alliance: the patriarchal one. Disparaged forms of patriarchal cultures find enough elements in common for mutual agreement. Languages and religious systems are banished and societal orders and political configurations are demonised by new central powers, but women’s oppression continues to give focus, a sense of solidarity and reciprocity between conquerors and conquered. There is a sense of tradition and ontological continuation. Without this, and the unquestionable Western subject, Grand Narratives would be effectively deconstructed, called to subpoena. These two elements are the main surpluses of the preservation of the order of life as we know it.

However, the end of the Original Nations’ Grand Narratives implied also a patriarchal crisis of gigantic proportions: husbands were required to give their wives to any Spaniard who wished to have sex, fathers to witness their daughters being taken as concubines or slaves without their agreement. Grandmothers became concubines and children sex slaves outside the control of the male eldership of society. On reading these stories, and the voices of protests from writers such as Todorov or Dussel on the Conquista, one gets the impression that it is authority which is questioned more than rape. When husbands came back from working in the mines, they needed to witness how their wives were forced to have sex with their bosses (Todorov 1987: 150). Guaman Poma de Ayala gives graphic accounts of Spanish men sexually abusing indigenous women while they slept (Pease 1980) which work at the level of denouncing male trespasses into other men’s properties. The issue here is one of possession, of men taking the property of other men, but not a discourse about the abuse of women. The fact is that the sexual Grand Narratives of Central America and the Inca Empire worked in a frame of property, similar to the Scriptural Commandment of men’s sexual rights over women. In the Conquista, women’s sufferings are a matter of economy.

The destruction of the Grand Narratives of the Americas did not come as the result of a hermeneutics of suspicion, or the realisation of the trace in the text, that element which is a movement leading us towards what the text tries to occult, hide and negate. No, economic exploitation was the decon-structivist clause, the doubting interrogation of naturalised, assumed authoritative narratives. In that, women’s oppression was to continue as part of an economic exchange. The pursuit of gold destroyed the idea of unity, the systematic thought of civilisations such as the Aztecs or the Inca Empire and introduced the plurality of European exploitation instead. As in a good deconstructivist process, it overthrew the power of an ancient monolithic discourse (built on the suppression of other discourses, those from internal processes of colonisation such as annexed cultures under the Aztec empire) and affirmed the ‘coming of the Other’ (Caputo 1997 a: 53). However, the Other came with its own law, its own closure of interrogations, while pursuing at the same time that passion for the impossible which lies at the base of the project of supplanting one civilisation with another. To take Tenochtitlan with 400 men and some tired horses could be a metaphor for the experience of surpassing limits of the unrepresentable and unpresentable (Caputo 1997 a: 33). That is to say the Original Nations’ civilisations proved to be beyond the comprehension of the symbolic of colonial Europeans.

Reading deconstruction from the end of the Grand Narratives in Latin America is an interesting exercise on a marginal positioning of ourselves as indecent theologians in the context of Christian theology. For instance, the taking of Tenochtitlan by a few soldiers and horses is such a disproportion. So is the imposition of Christianity on the religiously well-educated people of vast Latin American empires. A disproportion in terms of the non-relation, of the disconnectedness between world-views and asymmetric societies. But how did the guerrilla readings of the rebellious Latin Americans understand this through the dizziness of dislocation and repositioning of their order of things? How did the lemon vendors’ fore-mothers see the end of their accepted Grand Narratives? Perhaps through patriarchal patterns, the only thing they had in common with the Europeans, which provided the only sense of continuation. Without an understanding of submission there is no submission; without sexual constructs there are no Others. The fact that, historically, indigenous women survived through relationships with men (forced or voluntary), and men by their offerings of women to the Europeans (forced or voluntary), represents a common ritual in their efforts to reconcile and pacify. The exchange of women, together with gold, both to be ‘eaten’, absorbed, bodily incorporated, is the early symptom we have of the Conquista. There is no sense of disproportion there, although perhaps, in a general sense, of assimilation.

A simple assimilation retains by definition some of the substance of what has been embodied. If the death of the Latin American Grand Narratives had followed an epistemology of military structure, as Todorov and Dussel amongst others claim, nothing could have been assimilated and retained. A policy of ‘Tierra Arrasada (erased land) is the territory of the napalm bomb: neither people, nor animals nor plants survive; nothing will ever fructify in those fields. The incorporation of the Latin American forma mentis into the Spanish one implied a minimum dialogic process at a certain point, a symbolic co-operation. Incorporation transforms what it is eaten, but keeps it. The incorporation we are talking refers to a process of nourishment. The nourishment of the European Other did not happen by capital exploitation only, but by sexual agreements. As we shall see later, the worship of the Virgin of Guadalupe is a sexual religious agreement which re-symbolises the perdurability of the patriarchal system from one Grand Narrative to the other. In fact, women provide the continuation, the element of certainty and a certain memory, the memory of their subjugation. Thus women’s oppression gave a sense of normality to changing times, glossed and mythologised as in the case of the Virg...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Introduction: The fragrance of Women's Liberation Theology: odours of sex and lemons on the streets of Buenos Aires

- 1 Indecent proposals for women who would like to do theology without using underwear

- 2 The indecent Virgin

- Talking obscenities to theology: theology as a sexual act

- 4 The theology of sexual stories

- 5 Grandes medidas económicas: big economic measures: conceptualising global erection processes

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Indecent Theology by Marcella Althaus-Reid in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Religion. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.