1 General introduction

1.1 INTRODUCTION

For some years now the adolescent or teenage years have been recognised as crucial for the later emotional development of the individual. This is evidenced by the proliferation of publications devoted to this stage of the life span (e.g. Conger and Petersen 1984; Dusek 1991; Furnham and Gunter 1989; Furnham and Stacey 1991; Heaven 1994; Rice 1992; Sprinthall and Collins 1988). It is only more recently that research attention in both the medical and social sciences has begun to focus exclusively on adolescent health. Indeed, this development has been characterised by the establishment of journals such as the Journal of Adolescent Health and the Journal of Adolescent Health Care as outlets for research into all matters related to adolescent health.

There are, no doubt, several possible explanations for the growing interest in adolescent health. Two will be mentioned very briefly. The first is the HIV/ AIDS epidemic. It is well established that adolescents are increasingly at risk of HIV infection. Research data show that, although teenagers are aware of the dangers inherent in practising unsafe sex, this awareness is not matched by appropriate preventive behaviour (Crawford, Turtle and Kippax 1990; Moore and Rosenthal 1993). It is therefore crucial to understand all aspects of adolescent sexuality, adolescents’ perceptions of risky behaviours, and the effectiveness of behaviour-change programmes. Another reason for the interest in adolescent health may be that the onset of some behaviours such as cigarette smoking occurs in adolescence (Hill, White, Pain and Gardner 1990). Given the links between cigarette smoking and cardiovascular and pulmonary diseases in later life, it is important to understand just why some teenagers are at risk from cigarette smoking.

Implicit in this interest in adolescent health is the notion of adolescence as a period of change. It is during the adolescent years that teenagers experiment with new activities, and Jessor (1984) reminds us that many behaviours relevant to health (such as smoking and sexual activity) occur for the first time during this period. For this reason, therefore, it is important to understand all aspects of adolescent health.

1.2 DEFINITIONS OF HEALTH

Just what does it mean to be healthy? Health can be defined in a variety of ways and definitions have undergone substantial change over the years. In the nineteenth century the focus was on the physical aspects and this was followed in later years by an emphasis on germ theory (Millstein and Litt 1990). Later definitions viewed being healthy simply as an absence of any physical ailment, while the current tendency is to view health as involving body, mind, and social factors (Gochman 1988; Taylor 1991). Thus, many writers today view health as a function not only of one’s physical condition, but also of one’s attitudes toward health, one’s perceptions of risk, one’s diet, and the environment. For example, a teenager who believes that he or she is unlikely ever to become HIV positive is more likely to engage in risky behaviours such as practising unsafe sex or sharing needles. This teenager’s health status is therefore partly determined by cognitive as well as behavioural factors.

According to Gochman (1988), a definition of health should incorporate three perspectives. The first emphasises the biological aspect of health and is primarily concerned with such factors as physiological malfunctioning and germ theory. Also of relevance are certain overt symptoms of illness.

The second perspective concerns the social roles that individuals are expected to perform. Thus, those teenagers who do not perform the roles expected of them are likely to be labelled ‘deviant’. The third perspective is the psychological approach. Not surprisingly, this view emphasises the individual’s attitudes and perceptions. Thus, those who ‘feel’ well are likely to think of themselves as being healthy. According to this view, personal experience as well as cognitive factors therefore predict one’s wellness or illness.

These perspectives of health raise two important issues which require closer attention. The first is the idea that one is responsible for or in control of one’s health, and the second is a view of health referred to as the biopsychosocial model. Each of these will be briefly discussed.

Being responsible for one’s health

It was pointed out above that one’s health status may be determined, in part, by cognitive and behavioural factors. The teenager who believes that HIV infection is unlikely will be less inclined to adopt safe-sex practices. This suggests that many behaviours which have an effect on health are under the individual’s personal control. That is, one can choose to live a healthy life, or not. According to this argument, many diseases (e.g. lung cancer or heart disease) reflect lifestyle and personal choice (see also Chapter 8).

The concept of ‘locus of control’ has had an important influence on psychologists’ understanding of human motivation. So-called ‘internals’ take charge of their life events. They believe that they are in control and largely responsible for what happens to them. By contrast, those who are externally controlled believe that what happens to them is largely dueto luck or chance. There is a large research literature which has implicated locus of control in a wide range of health behaviours and attitudes. In brief, those who have a sense of personal control are more likely to practise healthy behaviours (Lau 1988).

A related concept is attributional style which is based upon a reformulated learned helplessness model of depression. A pessimistic or negative attributional style has been shown to be related to personality traits such as low self-esteem and loneliness as well as poor health outcomes (Peterson, Seligman and Valliant 1988). Locus of control and attributional style have important implications for health status and will be discussed in more detail in the next chapter.

The biopsychosocial model

The view that physical, psychological, and sociological factors play an important role in determining an individual’s health status is referred to as the biopsychosocial model (Engel 1977). According to Engel, the medical model that concentrates on the biological causes of illness is unable fully to explain all matters of health and illness. This is because the medical model excludes from consideration psychological and social factors and suggests that what deviates from the norm of biological variables must be ‘disease’ or ‘illness’. Medical practitioners find it tempting to apply this reductionist taxonomy to all cases of illness and to look no further than a biological cause for the aberrant health status.

According to the medical model, mind is separate from body. In other words, this approach is a single-factor model of illness (Taylor 1991) focusing on a very limited range of causes (usually biological) that tends to overlook other possible causal elements such as cognitive or psychosocial factors. Some would suggest that, quite often, it would be appropriate when reviewing an individual’s health status to consider psychological and social causes in addition to biological ones (Engel 1977).

The biopsychosocial model argues that the boundaries between ‘wellness’ and ‘illness’ are diffuse and that the medical model is therefore not always an appropriate yardstick for delineating the two. Unlike the medical model, the biopsychosocial model includes the patient as well as the illness. As Engel (1977:133) suggests:

By evaluating all the factors contributing to both illness and patienthood, rather than giving primacy to biological factors alone, a biopsychosocial model would make it possible to explain why some individuals experience as ‘illness’ conditions which others regard merely as ‘problems of living’, be they emotional reactions to life circumstances or somatic symptoms.

According to one recent review (Irwin and Orr 1991) there has, of late, been increasing communication across scientific disciplines. The authors found that many researchers are beginning to recognise that adolescent wellbeing, health, and illness are multidimensional in nature, comprising not only mind and body, but also environmental and legal elements. The biopsychosocial model of health and illness challenges medical practitioners to take all aspects of individual functioning into account when diagnosing and treating an illness (Engel 1977). Thus, they are being encouraged to acknowledge that health and illness are determined by multiple causes that interact with each other and that an adequate diagnosis can be made only once the biological, social, and psychological factors have been assessed (Schwartz 1982).

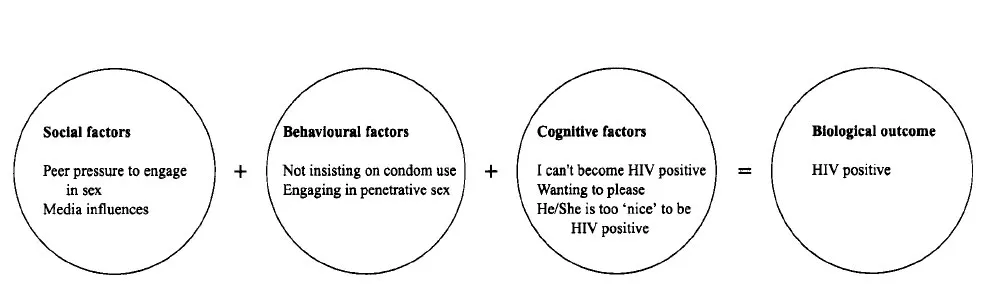

Practitioners are being challenged to show an interest in all aspects of the patient, to communicate with the patient, to take note of the patient’s life circumstances, and to be more sensitive to the personal problems of the patient. Thus, the challenge to the medical practitioner is to adopt a systems approach, that is, to recognise that the biological, social, and psychological aspects of the individual form an integrated system and that they work in unison in determining health (see Figure 1.1). In other words, it is suggested that changes to just one element of the system have the potential to affect other elements in the system.

Consider, for example, the teenager who is rejected by her peers at school. Her class mates avoid contact with her as much as possible. She is hardly ever asked to join in class activities, nor is she invited to social gatherings. As a consequence, she feels isolated and lonely, she is not eating well and has lost some weight. Unaware of the school situation, the family doctor treats the physical symptoms, disregarding their social origins. Not surprisingly, her physical condition remains largely unaltered.

Figure 1.1 A biopsychosocial approach to HIV infection among teenagers

The biopsychosocial model forms the basis for our definition of health. That is, it is recognised that biological and psychosocial processes play an important role in most manifestations of health and illness. In our examination of adolescent health, attention will be paid primarily to the psychosocial and individual difference variables that are involved.

1.3 CONCEPTIONS OF HEALTH AND ILLNESS AMONG ADOLESCENTS

This section will review adolescents’ perspectives on health and illness. We begin by examining the development of health beliefs among young people.

The development of health beliefs

A relatively large number of studies have investigated the health and illness beliefs of young children (e.g. Campbell 1975; Dielman, Leech, Becker et al. 1980; Gochman 1971), although fewer studies have concerned themselves exclusively with the adolescent years. Nonetheless, what evidence there is suggests that, as with other beliefs and values, there is a developmental sequence in the establishment of health beliefs. It would appear that the development of these beliefs is closely allied to individual cognitive development.

Cognitive-developmental studies

Burbach and Peterson (1986) recently reviewed several research projects that attempted to shed some light on the developmental stages of illness conception. The studies found that cognitively mature children are more likely to feel that they have some control over illness and the healing process. Very often, younger children are likely to view illness as the outcome of their own bad behaviour and they think of illness as a form of punishment. Older children are able to be more specific about symptoms and diseases. They can describe more clearly the nature of the ailment or just where the pain is. Younger children, by contrast, describe illness in ways that are less clear and specific (e.g. ‘I feel sore’).

Research findings also indicate that older children, rather than younger ones, are more aware of the relationships between the psychological, social, and affective aspects of disease (Burbach and Peterson 1986). Older children have the capacity, it appears, to use internal cues when determining their health status. On the other hand, younger children are more reliant on external cues (such as a bleeding finger) or external verdicts (such as the opinion of the family doctor) to determine their health status.

It is therefore clear that as children mature cognitively and are able to think more rationally, their conceptualisations of health and illness change. There are subtle, yet quite important, differences in the perceptions of children at various stages of development. Older children, especially those functioning at the formal operations stage rather than at the concrete operational stage (Santrock 1990), employ abstract reasoning in their conceptualisations of illness. Whereas older children are able to view illness as having multiple causes, younger ones have more simplistic and unsophisticated notions of health and illness (Millstein 1991).

Themes in conceptualisations of health and illness

When asked to describe what it means to be healthy or ill, children differ in the themes they employ to describe what they mean. For instance, one study of children aged between 6 and 13 years found differences in illness conceptualisation between the younger and older children (Campbell 1975). The children were surveyed while recovering in hospital and asked the following question: ‘Now I’m wondering about how you know when you’re sick. When you say you are sick, what do you mean? On one day you know you are well; on another you know you are sick. OK, what’s the difference?’ (Campbell 1975:93).

Several illness themes were uncovered and are shown in Table 1.1. Campbell (1975) found that there was some consensus between younger and older children as to the most salient or important themes. For instance, among both groups it was found that the vague and non-specific feeling states were more common definers of illness than questions of mood or altered role. It was also noted that older children were more likely than younger children to incorporate specific diseases or diagnoses in their definitions or to pay attention to altered roles. Despite some intergenerational similarities between mothers and older children, mothers’ definitions were more sophisticated, that is, they were more psychosocially oriented, they were more exact, and also found to be more subtle.

The results of Campbell’s (1975) research indicate that children even as young as 6 years of age have acquired c...