![]()

THEORETICAL SECTION

![]()

1. WHAT IS ICONOGRAPHY?

When one confronts a work of art, several questions may come to mind. Probably the first and most obvious question is “Who is the artist?” Art history has always concerned itself with attributing certain works of art to particular artists, and in the course of time most parts of the answer to the question “who made what?” fall into place.

Independent of the first stock question is a second, “What does the work of art depict?” or, more precisely, “What is the theme or subject of this work of art?” There has arisen a field within art history that is exclusively concerned with answering this question: iconography. To define the term more clearly, we can say that iconography is the branch of art history concerned with the themes in the visual arts and their deeper meanings or content. The word themes should be understood in a broad sense. Iconography considers a representation both as a whole and as a collection of details. For this reason, the meaning of a half-peeled lemon in a seventeenth-century Dutch still life could very well be the theme of an iconographic study. By “deeper meanings or content,” we mean other aspects of a work of art that, we may assume, were expressly included by the artist. These references to visual and literary sources and allusions to cultural, social, and historical facts will become clearer during the course of this chapter.

Iconography is derived from the Greek words, eikon and graphein, that is “image” and “writing.” Therefore, translated literally, iconography means “imagewriting” or “image describing.” Iconography, then, is not primarily concerned with the attribution of works of art or with their dating. While an iconographic analysis occasionally facilitates a precise dating or an attribution, iconographers usually leave such problems to other art historians. They also tend to avoid judging a work's aesthetic value. Every image—whether in folk art or Art with a capital A—is of equal significance in an iconographic investigation. Questions of attribution and aesthetics are subordinate to the iconographer's real objectives.

The first and most important of these objectives is to determine what is depicted in an artwork and to reveal and explain the deeper meanings intended by the artist. A second, intermediary concern involves tracking down the direct and indirect sources—both literary and visual—used by the artist. A further area of iconography is the investigation of certain pictorial themes, especially their development, traditions, and content through the ages.

In a work of art, one can distinguish three levels of meaning which simultaneously represent three stages or phases of iconographic research. The first level or phase is the exact enumeration of everything that can be seen in the work of art without defining the relationships between things. The “theme” or “subject” (the things that we see, brought into relation with one another) form the second level of meaning. The third level is the deeper meaning or content of the work of art as intended by the artist. These three levels of meaning or phases of investigation are called, respectively, the pre-iconographical description, the iconographi-cal description, and the iconographical interpretation.

In addition to the three iconographic levels of meaning, we may distinguish a fourth level or phase, which we may designate as the iconological interpretation. It is the task of iconology to look beyond queries about artist and subject to a third question: “Why was it created?” or, more precisely, “Why was it created just so?” With the help of the three iconographical phases and the iconological phase, we can define which tools are necessary for an iconographic—and, to a lesser extent, iconologic—investigation.

First Phase: The Pre-iconographical Description

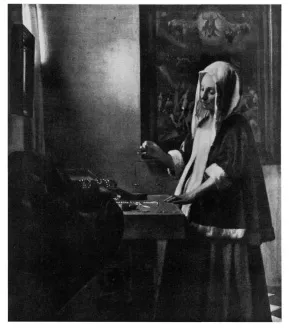

When we look at a picture for the first time, we automatically make a mental tally of everything that it portrays. Let us consider, for example, Jan Vermeer's A Lady Weighing Gold (figure 1). We see a woman, in an interior space, standing by a table. She holds a small balance in her right hand, while her left hand rests on the table. Her noticeably large abdomen seems to indicate that she is pregnant. On top of the table is a small box containing gold weights, a jewel-box with pearl necklaces, and several coins. On the wall in the background hangs a picture, and across from the woman there is another framed object, probably a mirror. The curtain is pulled shut, and the room is filled by an unusual, transfigured light.

1 A Lady Weighing Gold. Painting by Jan Vermeer.

This examination brings us to a rather rough enumeration of the “objects” and the situation in the picture. Without attempting to place things in relation to one another or to interpret them, we have drawn a pre-iconographical description.

When studying representative art, it is usually not difficult to produce such a description. In general, we can describe the things and situ-ations in a work because of their resemblance to the things and situations that surround us. We should always keep in mind, however, that the current meanings of things and situations do not necessarily correspond to those of previous centuries. It is also not always clear what the artist intended. For example, the large stomach of the woman in A Lady Weighing Gold could just as well be explained as the seventeenth-century fashion of women wearing cushions on their stomachs.

It is very important to scrutinize a picture carefully while enumerating its contents, for the pre-iconographical description is the prerequisite of every subsequent step toward a correct interpretation. If, for example, the art historian does not notice that the woman's scales in Vermeer's painting are actually empty, which means that she is weighing nothing at all, a subsequent interpretation would have missed the mark. Even such minute details can be of great importance.

One must also address a picture's composition during the pre-iconographical description. For example, in A Lady Weighing Gold, which we can now recognize as a misleading title, we should not fail to notice that the woman's head is located exactly in the center of the painting that hangs in the background. The colors that the artist uses may also be of importance and can occasionally have symbolic significance. During the pre-iconographic observation, the stylistic aspects of the visual arts are often neglected, although they are fundamental for the complete understanding and explanation of a work of art (see p. 19).

Second Phase: The Iconographical Description

The purpose of the second iconographic phase is to describe the “subject” of the work of art. As already mentioned, this task is one of the most important in iconography. In order to complete it, one must have an extensive knowledge of the themes and subjects in art, as well as the many ways they have been represented. Because artists have often portrayed the same subjects, there are often several if not many manifestations of most themes. For this reason, portrayals of themes become traditional, with executions of the same subject often resembling one another.

For example, we can compare the center panel of The Last Judgment, a famous triptych by Lucas van Leyden (figure 2), with an engraving of the same subject by Adriaen Collaert after Maerten de Vos (figure 3). The compositions of these two works—representations of the Last Judgment in which Christ returns to earth in order to judge the living and the dead—are fundamentally the same. This tradition of Last Judgment representations in the visual arts also enables us to recognize the theme of the painting on the wall in the background of A Lady Weighing Gold. We may almost assume that without this tradition, the viewer would not be able to recognize the subject of this painting within a painting.

In the course of time, art historians have developed terms that are useful in forming iconographic descriptions. The short descriptions, or titles, in this iconographic idiom often stand for extremely complicated representations. The description “Last Judgment,” for instance, implies much more than the two words suggest. Art historians and iconogra-phers in particular must be familiar with these short descriptions and their meanings since they play such an important role in discussions about art.

The range of themes and subjects in art is quite extensive but certainly not limitless. One may procure with relative ease a sound knowledge of frequently depicted subjects by looking through thematically ordered collections of reproductions and by taking care to notice themes and subjects when viewing museum exhibits and reading art-historical literature. In so doing, one learns to recognize the fundamental differences between various thematic areas. For instance, biblical and classical-mythological scenes may be distinguished from each other primarily by settings and by the clothing and accoutrements of their figures.

In this second phase of research we should ideally be able to identify figures and persons. If we succeed, it is easier, on the whole, to identify the subject of the work. However, it should be noted that the identification of personified abstractions is already part of the third phase. More about the identification of persons and figures will follow in the fourth chapter, “Symbols, Attributes, and Symbolic Representations.”

A profound knowledge of the themes and subjects in art is absolutely essential in the study of iconography, but a familiarity with literary sources of artworks, such as the Bible, is also an indispensable tool. A piece of literature can be a direct source if the artwork is based on the text, or an indirect one if the artist models his work on another work that is in turn based upon a literary source. In the first case, one can expect a more or less exact “pictorial translation” of the text, while in the indirect method, iconographic traditions may play a more important role. Often, of course, artists have been influenced by both literary sources and the iconographic tradition. During an iconographic investigation, the iconographer should naturally endeavor to discover which works of art could have influenced the artis...