1

A Century of Dynamism

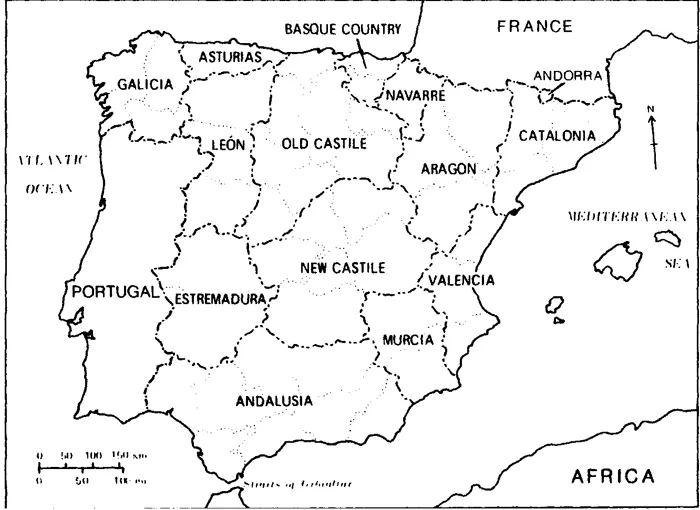

Spain stands at the western extreme of the European continent. It is a large country, some 500,000 square kilometers, with a large variety of physical environments. The most striking feature, as Figure 1.1 shows, is the prevalence of mountains. Spain is, after Switzerland, the most mountainous country in Europe. The Pyrences, at a constant height of at least 5,000 feet which exceeds 11,000 in places, block the entrance to the Iberian pensinsula. The Cantabrian range, which averages between 5,000 and 6,000 feet, cuts the northern tier, Galicia, Asturias, Santander and the Basque Country, from the rest of the country. After a narrow gap, the Iberian Mountains begin, running roughly parallel to the Pyrences. The vast central meseta is broken into two by the central sierras, the Guadalupe and the Guadarrama. In the south the Betic Cordillera, an irregular series of mountain ridges broken by north-south rifts, contains the country’s tallest peak, at 11,420 feet.

Beyond the mountains, the country is dominated by the vast central tableland. The northern meseta has an area of some 15,000 square miles and an average altitude of 2,700 feet. The southern meseta is three times as large but, at less than 2,000 feet, has a lower average elevation. The coastal lowlands are very small. Catalonia, for example, has a very narrow coastal strip which is brought to an abrupt end by mountains only twelve miles inland. The only large lowland area is the Andalucian plain.

The mountains make movement from one region to another difficult and even obstruct movement within some others, such as the Ebro basin and the Cantabrian strip. The principal rivers, the Tagus (600 miles), the Ebro (540 miles), the Ducro (525 miles), the Guadiana (465 miles) and the Guadalquivir (395 miles), are too fast flowing or suffer too much silting at their mouths to compensate much as aids to communication and transportation.

Spain also has a tremendously wide range of climates, from temperate in the north-west to semi-arid in the south. Some areas in the north-west get between 60 and 70 inches of rain per year but some two thirds of the country is deficient in rainfall, that is, does not get enough rain to sustain normal plant growth for four months out of twelve.

There are three main climatic zones. The maritime zone, from the north coast to the Cantabrian mountains which includes Galicia, Asturias, Santander, and the Basque Provinces, has mild winters, abundant precipitation spread throughout the year and warm, but not hot, summers. (Few Britons take vacations here. The weather would remind them too much of home.) The inland areas, the mesetas, the Ebro basin and adjoining mountains, have a continental climate. Temperatures fluctuate greatly, both from winter to summer and from day to night. The summers are very hot and the winters very cold. In January the average temperature in many parts of the northern meseta is only a couple of degrees above freezing. Rainfall is low and irregular throughout the year. The south frequently experiences alternating drought and flood. The final climate is the Mediterranean zone, which takes in the Andalucian plain and the southern and eastern coastal strips. There is little variation in temperature from winter to summer and in both seasons temperatures are higher than in the interior. The hottest area is between Seville and Córdoba, where the mean temperature in July and August is between 85 and 88 degrees Fahrenheit and readings of more than 100 are common. Rainfall is unreliable. This is what package tour operators mean by ‘Spain’.

A country’s basic geographic and climatic facts of life do change, albeit very slowly. Landscapes, however, are shorter lived. By the economic activities they choose to undertake men and women can change the face of a country very quickly: woodlands disappear, the frontiers of cultivation expand—or recede— rivers are polluted, wildlife is killed off. While very often ecologically harmful, such changes are also indicators of economic dynamism and demographic expansion. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries the face of Spain changed markedly, as industrial development scarred the beauty of many rural landscapes and an expanding agriculture reclaimed land long given over as privileged pasture to the sheep. When he travelled through Spain in 1796 Robert Southey noted that ‘rich tracks of land are uncultivated …we have often travelled five or six hours without seeing any trace of man except the agreeable memento of a few monumental crosses’.1 Had he been able to return five or six decades later he would have had to look much harder to find such a scene.

An Evolving Economy

The Spanish economy in the nineteenth century and the first decades of the twentieth presents something of a paradox. Industrialization began early, in the latter decades of the eighteenth century and even though Spain experienced continual economic growth over the nineteenth century it fell further and further behind other European countries such as Britain and France and, after 1870, even Italy. As Leandro Prados has put it ‘growth and backwardness are two sides of the same coin…long term sustained growth was accompanied by backwardness in relative terms’.1 The Spanish pattern of economic development was not identical to that of north-western Europe, but it was even less like that of the contemporary Third World. Spain was not, as Nicholas Sánchez Albornoz has claimed, ‘an underdeveloped economy avant la lettre.2 It was fully a part of European economic development although sui generis, with a ‘sustained increase in per capita income after 1830’. From 1780 to 1930 ‘Spain experienced a moderate but constant transformation which followed its particular route to modernization’.3 Spain was not an economic failure, as Jordi Nadal has called it,4 nor was it trapped in stagnation. Its economy was growing and changing, but more slowly than those of other countries. It was a laggard.

Agriculture

In 1914 agriculture was still the core of the economy: it produced almost 40 per cent of the national income and employed over 60 per cent of the labor force, compared to 18.5 per cent in manufacturing and mining. Even in 1930 it remained the dominant sector, employing almost half of all working Spaniards, while wines, fresh fruit and other agricultural products accounted for 35 per cent of total exports, down only 10 per cent from 1850. There are few reliable statistics for Spanish agriculture in the first half of the nineteenth century but contemporaries believed, and historians generally agree, that production increased substantially, keeping pace, at least, with the increase in population. Certainly throughout the first half of the century, Spain was able to feed itself, and in a number of years export surplus grain. This increase culminated in the 1870s and was followed by decades of crisis at the end of the century and then by a strong recovery in the twentieth century.

There were a number of reasons for this expansion of production. Josep Fontana has argued that the loss of the American colonies and the wealth derived from them forced Spain to cut back on its imports from Europe, basic foodstuffs among them.5 The decree of August 5, 1820, issued by a liberal government, banning imports of wheat and other key cereals so long as the price in Spain remained below stated levels was a major stimulus to domestic production. This policy of rigid protectionism was retained until 1869 and over the course of the half century in which it was in effect grain was imported during only four subsistence crises.

This expansion in production was due almost entirely to the extension of cultivation. The only estimate of the actual amount of land brought into cultivation is 4 million hectares between 1818 and 1860, although the reliability of the sources on which it is based has been questioned.6 There was not much in the way of technical improvements before 1850 and yields of wheat and other grains actually declined between 1800 and 1860. There is evidence that by the 1860s grain cultivation was becoming more sophisticated, at least in Andalucia, as some leading landowners invested in modern agricultural machinery. François Heron has gone so far as to claim that there was ‘a vast movement of mechanization in the Andalucian countryside in the second half of the nineteenth century’.7

Wheat producers benefited from a growing domestic market as well as from exports to Cuba and, until 1881, regular exports to other countries. After that date, however, Spain imported much more wheat than it exported and failed to generate a trade surplus in grains before the First World War. Improvements in transportation and the opening of the American west brought grain from the Ukraine and the United States into Spanish ports at prices below those for Castilian grains. Castilian landowners responded, as did their German and Italian counterparts, by lobbying for increased protection, which they got in 1892. They also took land out of production, almost 3 million hectares between 1888 and 1893.

Figure 1.2Spain: Historical Regions

Castile was the region most affected by the expansion of cereal cultivation. For most of the region the nineteenth century brought what Sánchez Albornoz has called an ‘economic involution’.8 The economy became less complex and diverse than it had been under the Old Regime and more dependent on a single agricultural product, grain. Wool production did not expand and small-scale textile manufactures were killed off by Catalan products. The agricultural sector was oriented to the market, as it had long been, but the changes stemming from the liberal revolution did not lead to the investments required to improve efficiency and increase output.

The economy of the interior had long been dominated by the needs of the capital. This did not change in the nineteenth century, when Madrid continued to shape the economy of its vast hinterland, which covered virtually the entire central meseta. David Ringrose has summarized this relationship:

Because of its dependence on primitive overland transport, the size of Madrid was a factor of extreme importance in the economy of Castile, if only because the city constituted a market for agricultural products with few alternative sources of supply. The structure of that market was such as to provide its hinterland with only a limited range of incentives, and the city could not provide the variety and depth of demand needed to draw the Castilian economy out of subsistence agriculture embedded in a self-contained regional economy. Madrid could mobilize surpluses that traditional systems of rural control accumulated, but had little effect on productivity.9

The changes in land ownership prompted by the liberal revolution allowed for ‘agricultural commodities [to be] more uniformly accumulated as rents rather than tithes, or through direct management…before they moved into supply systems focused on Madrid’ but did not produce any more basic changes.10

Orientation to the market and new opportunities did produce important changes in some branches of agriculture. Perhaps the most sweeping took place in the sherry producing region of Jerez de la Frontera. Export markets for sherry began to expand in the 1840s, prompting the merchants who controlled the trade ‘to consolidate sherry production from vine to wine’.11 They sought to purchase existing vineyards, which were in the hands of peasant owners, or expand cultivation into new, less suitable lands. The area in vineyards increased by 50 per cent between 1817 and 1851 and by another 50 per cent in the next twenty years. This option was highly capital intensive: in addition to the purchase price of the land, owners had to buy the vines, put up buildings and fences and buy wine presses—and then wait four years for the first crop of grapes. However, the cheaper sherry which was produced from these new vineyards found expanding markets in Britain in the 1860s and, as a result of the phylloxera epidemic, in France after 1875. The peasants from whose grapes the traditional, expensive sherries were produced were faced with rapidly declining prices, from about 110 pesetas per butt in 1865 to 40 in 1880, and many were forced to sell their land. By the end of the century the owners of the large sherry firms, many of them such as Duff, Garvey and Byass originally British, controlled most of the vineyards and had assumed positions of local social and political influence.

Jerez was not the only place in Spain for which wine production was important. Vineyards were crucial to the Spanish economy in the nineteenth century. The area under cultivation grew four times over the course of the century, much of this in Catalonia, and production increased six times between 1860 and 1890 alone. The importance of wines lay in the fact that they were a bulwark of Spanish exports: they accounted for one-third the value of all exports in 1857 and their weight increased until 1890. And even though phylloxera hit the country hard in the 1880s, Spain remained the leading wine exporting country in Europe from 1880 to 1914. On the eve of the First World War wines were the country’s second most important export, accounting for only slightly less value than did minerals.

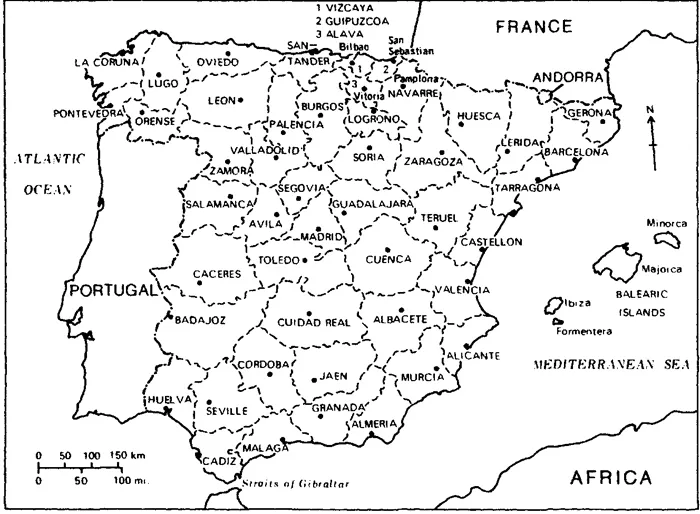

Figure 1.3Spain: Provinces

Two other crops, oranges and olives, both of them exported in large quantities, also advanced during the nineteenth century. Oranges were grown in Valencia using both irrigation and fertilizers. The area dedicated to orange trees increased from 2,675 hectares in 1872 to 37,500 in 1915 and the value of exports rose from 2.7 million pesetas in 1855–9 to 57.7 million in 1905–9. Olive cultivation underwent a tremendous expansion, especially in the first three decades of the twentieth century, when the area under cultivation increased by 50 per cent. Traditionally grown in Seville and Córdoba and the lower Ebro, olive trees expanded into eastern Andalucia. The early twentieth century also saw an improvement of the quality of the oil produced, at least in western Andalucia, due both to better care of the trees and to more advanced processing techniques. In 1914 olive oil was Spain’s tenth most valuable export.

Livestock production also recovered from its nineteenth-century decline, especially in regions like Asturias where a burgeoning urban population provoked what is known as a ‘dairy revolution’. Overall, the live weight of livestock increased by 63 per cent between 1900 and 1930 and the value of livestock production more than doubled, from 589 million pesetas in 1900 to 1.3 billion pesetas in 1930.

In sum, Spanish agriculture was more dynamic and varied than has often been pictured. Production of basic foodstuffs was more than able to keep pace with population growth, especially after 1895. Grain production increased slightly more than population between 1795 and 1895 but between 1895 and 1925 output per head increased 0.72 per cent per year. Spanish agriculture became increasingly export oriented, but it was not dependent on a single crop and was able to respond reasonably quickly to changes in demand and market conditions. As Garrabou and Sanz have observed, ‘the fact that Spanish farmers could feed a growing population better and better and meet the needs of the industrial nations with the rapidity, variety and quantity that they did allows us to maintain that we are far fro...