This is a test

- 260 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Iain Chambers approaches the often overlooked details and textures of popular culture through a series of histories which show how it becomes continually remade as each of us defines our own urban space.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Popular Culture by Iain Chambers in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Popular Culture in Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

THE OBSCURED

METROPOLIS

THE OBSCURED

METROPOLIS

1 URBAN TIMES …

It is in the city that contemporary popular culture – shopping and video arcades, cinemas, clubs, supermarkets, pubs, and the Saturday afternoon purchase of Saturday night clothes – has its home. Take away this context and present-day British popular culture becomes incomprehensible. But it is not simply the nineteenth-century explosion in urban population that explains the contemporary city and sets it apart from both rural society and previous urban experience. It is industrialism, conspicuously concentrated in the ingression of speed and measured time into everyday life – from the train, tram and telephone to the factory system and the sharp separation of work from leisure – that directs cultural life into new networks, following fresh imperatives.

We will discover, however, that for many observers much in the modern city and in the wake of industrialism has been considered foreign, usually American-inspired, distinctly ‘un-British’. These views, this critical and institutional consensus, which has continually attempted to match ‘culture’ with ‘Britishness’, deliberately ignore another history. This is a history drawn from the structured and experiential landscapes of everyday life; from its constraints and possibilities, from its textures, from the comfort of its details.

It is this other side of urban life that I propose to look at. It is here, I will argue, that what is peculiar to contemporary popular culture has its home. It is here that both its connection and break from the past will be found. And it is here that popular culture’s central role in the making of urban culture as a whole is to be appreciated.

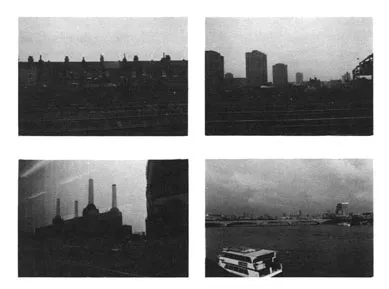

View from a train

When one crosses a landscape in an automobile or an express train, the landscape loses in descriptive value, but gains in synthetic value. … A modern man registers a hundred times more sensory impressions than an eighteenth-century artist. (Fernand Léger, 1914)

We live in a designed world. (Farr, 1964)

We begin with a view. South London. From the train there are glimpses of Croydon. A genteel suburbia full of those gabled roofs favoured by domestic architects in the 1920s and ′30s; many trees.

Near the railway lines inner-city, commercial overspill finds new accommodation, and cheaper rents, in smoke-glassed, air-conditioned offices. Many are empty: ‘Space to Let’. Croydon gives way to inner London. There are now few trees.

Low, nineteenth-century housing (‘labourers’ dwellings’ would have been the term) flank the tracks. Then come the concrete acres of Clapham: council tower blocks and housing mazes of recent construction.

For a moment, we see the bold, futuristic silhouette of Battersea Power Station, then the train crosses over the Thames near Westminster to arrive in Victoria.

I have begun with this ‘reading’ of the city as it allows us to appreciate at a glance how the design of the world most of us inhabit – housing, railways, offices, suburbia, government, industry – is built into the ‘very bricks and mortar’ (Clarke, 1979) of our daily surroundings. This is the recognizable syntax of urban life. And, like all space, this urban arrangement ‘is charged with meaning’ (Castells, 1979). It is also charged with power. For the material details of urban life – our houses, the roads we live in, the shops we frequent, the transport we use, the pubs we visit, the places we work at, the advertisements we read in the papers and the streets – suggest many of the structures for our ideas and sentiments. It is this everyday experience that we invariably draw upon, whether in choosing a record or expressing an opinion on the news.

Urban shock

1900: Britain is essentially an urban society. Eleven years later official figures would indicate that 32 of its 40 million inhabitants lived in towns. Such extensive urbanization, then without precedent in either Europe or the United States, was dominated by London. The capital contained 20 per cent of the population of England and Wales. This urban, economic and cultural concentration, aided by geography and by political stability, and reinforced by a national press, was highly significant. In Britain, metropolitan styles have been rapidly assumed as national fashions.

Nineteenth-century British cities, however, were hardly the product of systematic planning. When we picture them they are dominated by sprawling, brick-built factories and warehouses, dirty canals, and row upon row of low, grimy housing: the factory-chimneyed skylines of Manchester; grim, barrack-like, tenement blocks in Glasgow; the teeming life (and diseases: cholera, TB, scarlet fever, syphilis) of London’s streets. The earlier Georgian model of geometrical symmetry – squares, circles, crescents and wide, straight roads: Bath, Cheltenham, London’s Regent Street – was swamped by the nineteenth-century explosion in population and the brutal rush of the industrial city bursting over the countryside and previous urban patterns. The city was no longer an organic unity, the hub at the centre of a wheel, but an uncontrollable and unseemly growth.

For many, the chaotic assemblage of hastily thrown-up tenements, filthy, undrained streets, smoke-belching factories, and crowds everywhere, represented a breakdown in order, an ‘unnatural’ society (Dickens, 1911). The city cut into, and separated itself from, nature. It elicited the novel aesthetics of shock, not contemplation. The harmony of the community was replaced by the incommensurable variety of the metropolis. Physical chaos was matched by a sense of cultural disorder. The present-day theme of the city as a place of tragedy, an experience of crisis, was as familiar to the Victorian critic as it is today. And although it was later to be investigated through the invention of two new literary genres – the detective story and science fiction – British writers, with the partial exception of Dickens, found the city streets inscrutable: a metaphorical ‘Africa’, occasionally explored, usually ignored.

It was as though culture could not hope to survive the rapid mechanisms of city life. Its delicate sentiments would be crushed and lost in the anonymous crowd. In the subsequent outcry against the inhuman conditions of factory life, against slums and urban poverty, English literary and critical writings have also consistently voiced the fear of ‘another country’, of an alien ‘way of life’.

Whistles, horns, sirens and clocks

Central to the sheer physicality of change in the nineteenth-century city was a new sense of time. Time began to be accumulated in collective labour, in machinery and mechanical production, in the factory system. It escaped from the natural clock of day and night and the seasons and became a social construction. It was divided up into sequential units to be measured, defined, fought over, and consumed. This led to a long struggle over whose time it was: over the length of the working day, over establishing the principle of ‘over-time’, over the workers’ rights to the two-day weekend and the yearly paid holiday.

Working-class and trade-union agitation to establish the temporal limits of factory labour gradually gave a new sense to urban working-class life. As industry supplanted more local forms of production, and cities expanded into separate zones for factories and dwellings, the earlier connections between work, the home and local culture became less immediate. The search for pleasure, at least for men, took place outside the factory gates and often increasingly outside the house, in the sphere of leisure, with personal ‘free time’ spent in the pub, at the dog races, breeding pigeons, tending allotments, and fishing.

There, above all for men (women’s domestic drudgery was rarely granted the status of work and therefore their ‘leisure’ remained more ambiguously defined), was the opportunity to dress up, look ‘smart’ or ‘flash’, to translate your imagination into a youth style, into dancing, into ‘having a good time’, into ‘Saturday night’.

(Peter Osborne)

Suburbia

The introduction of new, mechanized rhythms and their disciplined timetables, along with the noise and dirt of rapid economic and urban growth, produced a series of shock waves whose effects went far beyond the initial horror expressed by Victorian writers and critics. Those who could afford to choose where they lived abandoned the city centres to day-time commerce and administration, to philanthropists and sensationalist journalism, to the working classes and the urban poor. London’s extensive railway network and underground carried the better-off, and the aspiring better-off (the black-coated army of lower-middle-class clerical workers) away from the ‘slimy streets’ and ‘screaming pavements’, from the ‘abyss’ of Jack London’s East End, travelling over and under the ‘rookeries’, ‘dens’ and slums to the residential areas that ringed the city. There, in the ‘supreme ambivalence’ of tree-lined suburbia, citizens of the business world and the professional classes lived in ‘a gesture of non-commitment to the city in everything but function’ (H. J. Dyos in Cannadine and Reeder, 1982).

So, for the upper and many of the middle classes, the nineteenth-century city became a foreign territory; an alien presence whose ‘opaque complexity’, then as now, was ‘represented by crime’ (Williams, 1973). There is a neurotic continuity here that runs from the ‘street Arabs’ of the 1840s, through the ‘gangsters’ of the 1860s, the ‘un-English’ Hooligan of the 1870s, and the Northern ‘scuttler’ and his ‘moll’ in the 1890s, to the Hollywood-inspired motor bandits and bag snatchers of the 1930s, the ‘spivs’ of the 1940s, the ‘Americanized’ teddy boys of the 1950s, and the ‘New York-inspired’ black ‘muggers’ of the 1970s (Pearson, 1983). But these were only lurid symptoms. For it was the city itself that represented a crime against nature. Peopled by a ‘new race … the city type … voluble, excitable, with little ballast, stamina or endurance’ (Charles Masterman in Stedman-Jones, 1982, 92), its obscure complexity was ultimately seen as a threat to the ‘British way of life’.

Taming the wilderness

The city, therefore, although initially abandoned to the working classes and the urban poor, had eventually to be reconquered, the ‘wide wilderness of London’ (Dickens, 1911, vol. 2, 279) to be tamed. The publication in the 1840s of a series of government Blue Books had revealed the appalling sanitary conditions in Britain’s major towns. This, and subsequent housing, health and education legislation through the course of the century, formed the official framework of what would become the ‘civilizing mission’ to the poor.

For poverty and urban squalor, at least viewed from the comfortable prospects of a Victorian drawing room, were generally considered to be the result of immorality (the poor were ‘philistines’ – riddled with atheism, sexual licence and ‘the demon drink’), not economic and social forces. Moral rearmament, in the form of religion, the temperance movement, schooling and education, was despatched to the ‘Hottentots’ in the slums of ‘darkest England’. But to be educated for your place in society called for moral discipline rather than disinterested knowledge. It is not surprising that personal accounts of working-class education at the turn of the century often reveal the hollow nature of schooling and its frequent interruption by pupils’ strikes, truancy and ‘larking about’ (Humphries, 1981).

Following the rough justice of the police and the extension of schooling to all, the ground was prepared for an individualistic, ‘self-help’, ‘respectable’ British citizenship to grow. The idea of respectability – a medium for moderation in all matters social, sexual and political, an appeal to that subconscious area that the American writer Norman Mailer once called the ‘psych...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- General editor's preface

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction Popular culture, popular knowledge

- Part One The Obscured Metropolis

- Part Two The Sights

- Part Three The Sounds

- Part Four Conclusions

- Further materials

- References

- Index