This is a test

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

In this extensively updated second edition, including an up-dated index and bibliography, J. W. Roberts explores the main features of Athenian life in the latter half of the fifth century BC.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access City of Sokrates by J.W. Roberts in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

1 COUNTRY AND TOWN

The self-governing political community or polis of Athens comprised, strictly speaking, just the citizens (politai), a privileged minority of men within the total population. Whereas we might say, ‘Athens decided…’, the Greek idiom was to say, ‘The Athenians decided…’, and that meant that the citizens, rather than the entire adult population, had decided.

Geographically speaking, a Greek community normally comprised an urban settlement (asty) built around a defensible hill (akropolis), which was near, but not too near, the sea, together with its surrounding territory (khora), which was bounded by the sea or by mountains, beyond which lay the territory of some other community. And so it was with Athens, except that her frontier with Megara was not a mountain range.

The city of Athens developed round a citadel, the Akropolis. Its harbour, Peiraieus, was four miles distant. The surrounding territory, Attike, was roughly triangular in shape—the northern side of the triangle running from the south-eastern slopes of Mount Kithairon along the crest of Mount Parnes to a point on the coast north of Rhamnous, the eastern side running south from that point to Cape Sounion, and the third side running north-west to Kithairon. The total area of more than 900 square miles constituted a khora large by Greek standards, but no place in Attike, not even Sounion, was as much as thirty miles from Athens or fifteen from the sea.

No town or village in Attike was nearly as populous as Athens or, by the middle of the fifth century, Peiraieus. At the end of the sixth century, Kleisthenes had divided rural Attike into more than 100 administrative ‘demes’ or villages with their inhabitants. These rural demes were preexisting settlements, and varied greatly in size, the largest of them being Akharnai (Thucydides 2.19.2). (Kleisthenes also divided the walled city of Athens into five demes, resembling our wards.)

The natural resources of Attike were not very great. There were plains—round Athens, beyond Hymettos, beyond Aigaleos (the Thriasian plain), and beyond Mount Pentelikon (the plain of Marathon)—but the soil was light. Furthermore, rainfall was low and there were no considerable rivers. The river Kephisos flowed by Athens, another by Eleusis, and a stream watered at least part of the plain of Marathon; but there was not enough water in any of them to permit extensive irrigation or navigation. Thus there was little fodder suitable for horses or even cattle. Donkeys and mules were commonly used as beasts of burden. Sheep and goats, as well as providing wool and hair for textiles, also provided milk, from which cheese could be made. Many small farmers or peasants kept poultry and pigs. Only the biggest land-owners could afford to keep horses (for sporting or military purposes) or more cattle than a yoke of oxen or cows as draught-animals.

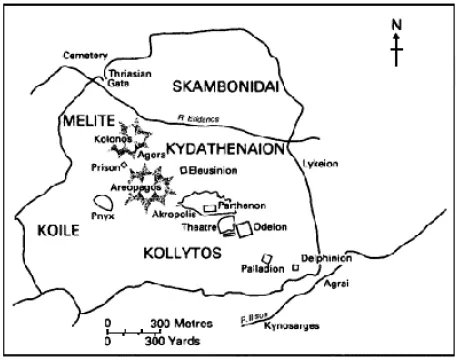

Figure 4 Athens c. 400 BC

Much of the arable land was devoted to growing cereals, but even so it is doubtful whether by the mid-fifth century Attic grain could feed more than half the population. Such grain as was grown was less commonly wheat than barley, which throve better on the light soil; so barley cakes and porridge were important parts of the national diet. Market-gardening flourished, especially around Athens. The mild winters permitted a long season. But for moderate supplies of fish, the national diet would have been largely vegetarian. It was rare for most Athenians to eat meat except on the occasion of public sacrifices, when the carcases of the victims were distributed among the congregation.

By historical times the deforestation of Attike was far advanced. Charcoal-burners were active on the southern slopes of Parnes; timber for shipbuilding had to be imported. The scrub on Hymettos supported many swarms of bees, and the honey they produced served the same function as sugar today. Two fruit-trees that did flourish were the olive and the fig, and so did the vine. Olive oil was important in cookery and, when burnt in lamps, as a source of light. It was also used for anointing the body. Attike produced enough oil to leave some for export.

Oil and wine were stored and transported in earthenware vessels, and there were plentiful supplies of reddish potter’s clay to be obtained from Athmonon and elsewhere around Athens. The quarries on the western side of Pentelikon yielded inexhaustible quantities of marble. Of much greater economic importance were the lead and silver mines in Laureion. Like the quarries, they were the property of the community, and they contributed very greatly to its prosperity. Finally, Peiraieus afforded superb natural harbours, there being in addition to the main harbour of Kantharos two smaller harbours on the east side.

When the Peloponnesian War, fought between Athens and the Spartan alliance, broke out in 431, most Athenians still lived in country villages, but the opening years of that war were to reveal, to all who cared to look, that Athens by then was more dependent on the sea than on her countryside. The pattern of rural life was the same as had in large part originally shaped the calendar of religious festivals, which provided the setting for so much of the cultural life of the city. Though there were gentlemen farmers living in Athens but owning large estates in the country, worked by slaves under the supervision of slave bailiffs, most farmers were small-holders owning perhaps a single slave. (The Greek word georgos covered a wide social range—from gentleman farmer to hardworking peasant and tenant farmer.) Primogeniture not being recognised in Athens, there was a tendency for ancestral lots of land to be progressively subdivided, with the result that some properties were hardly large enough to support a family.

For all who grew cereals (and almost all will have grown some barley—very likely between their rows of olive-trees or vines), the working year began in October. Only with the coming of the autumnal rains was ploughing possible. There was then a busy period of two or three months, during which the ground had to be prepared and the seed sown in time for growth to begin before the coldest part of the winter. There was little to be done during January and February. Spring called for renewed activity, culminating in harvesting in May and threshing in June. There was again little to be done in July and August. Then it was time to gather the grapes and figs, and later the olives.

One of the recurrent motifs of history is tension between country and town, and Athens was not free from it. The failure of the farmers to improve their methods was a sign of a conservatism that was bound to disapprove of urban innovations. The Greek words for ‘urban’ and ‘rustic’ (asteios and agroikos) also mean ‘witty’ and ‘boorish’. Our dependence on mechanical aids may lead us to exaggerate the distaste that an Athenian felt for a long walk. Andokides (1.38) mentions without comment a walk from Athens to Laureion, a distance of some twenty-six miles. It may therefore be that Athenian farmers were prepared to walk a long way to attend important meetings of the sovereign Assembly, provided that they did not fall at the two busiest times of the year. On the other hand, because they did not live in the city, they were bound to be ignorant of the background of many of the matters debated in the Assembly. ‘There’s a lot that passes us by’, says the Chorus of Farmers in Aristophanes’ Peace (618). We may assume that few farmers would dare to speak in the Assembly: their ignorance, their clothing and their unpolished speech would expose them to ridicule. Since very few farms were anything like self-sufficient, and friendly neighbours could not always supply what was lacking, most farmers had to buy and sell in the city from time to time. An Aristophanic farmer (Assemblywomen 817ff.) speaks of selling his grapes and going to the urban market-place or Agora for barley-groats. In the Agora farmers were liable to be cheated by the quicker-witted townsfolk.

The original town of Athens comprised the Akropolis and a settlement on its southern side. By the fifth century the centre of city life was the Agora, an area between the Areopagos or Hill of Ares and the River Eridanos that appears to have been chosen as the main square early in the sixth century. It is possible to outline the course of public building in the Agora and elsewhere in the city from the sixth century, and to do so gives an insight into public concerns and priorities.

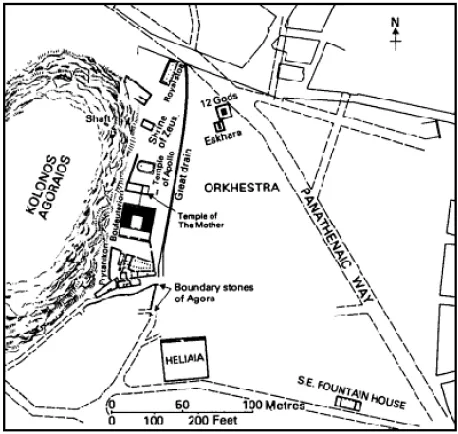

While Athens remained small, the Agora, as well as being the formal and informal meeting-place of the citizens, accommodated the principal administrative buildings, some sanctuaries, many stalls for the sale of goods, and also dramatic, musical and athletic contests, which were held in the Orkhestra or dancing area. What may have been administrative buildings going back almost to the time of Solon were situated on the west side of the square at the foot of Kolonos Agoraios or Market Hill. Solon’s reforms of 594 failed to avert the threat of one-man rule, and for most of the second half of the century Athens was ruled by the tyrant Peisistratos and, after his death in 527, by his son Hippias. (A Greek tyrant was a usurping but not necessarily tyrannical ruler, or a kinsman who had succeeded to his rule.)

In 522/21, when he was Arkhon, or chief magistrate, the grandson and namesake of Peisistratos dedicated the Altar of the Twelve Gods in the north-west corner of the Agora. It was situated on the south side of the Panathenaic Way, which ran diagonally across the square from north-west to south-east. (The Panathenaia was Athens’ chief festival honouring Athena, and an important component of the festival was a procession along the Panathenaic Way to the Akropolis.) The altar became a place of asylum and was the point from which distances were measured

Figure 5 The Agora c. 500 BC

(Herodotos 2.7.1). An aqueduct was laid to bring water to a new fountain-house in the south-eastern corner of the square. This public provision of running water will have been a welcome alternative to privately owned wells. A large structure in the south-western corner is thought to have been an open-air law court.

In 514 Hippias’ brother, Hipparkhos, was assassinated by Harmodios and Aristogeiton. They had meant to kill Hippias as well, but their plan miscarried and they were executed. In 510 the tyranny was brought to an end by the armed intervention of the Spartan king Kleomenes. There followed two years of aristocratic feuding, and in 508/7 Kleisthenes brought before the Assembly measures leading to the establishment of ‘moderate’ democracy. The memory of the two tyrannicides was highly honoured by the erection near the Orkhestra of their statues in bronze.

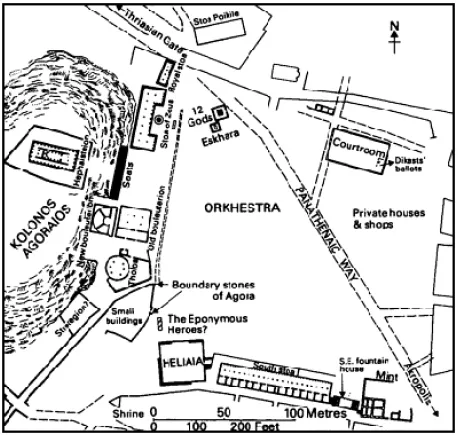

The Agora square was regarded as sacred, and it was now marked off with marble boundary stones. Those accused of homicide or convicted of various other heinous crimes were excluded from it by law. In a wider sense, the Agora was not only the defined square but the whole commercial area, including much of the Kerameikos or Potters’ Quarter to the north-west. Down the west side of the square a great stone drain was laid to carry surface water away to the Eridanos. It was probably now that a quieter place was found for meetings of the Assembly—on the hill called Pnyx, a quarter of a mile to the south-west. The new site was not more spacious than the old, but it did provide a more steeply sloping auditorium. Only if the Assembly had voted to hold an ostracism, to determine whether some prominent citizen should be sent into exile for ten years, did the citizens now gather in the Agora for a strictly political purpose. Central to the new constitution was the new Council of 500. To accommodate it, a south-facing square Council-house was built on the west side at the foot of Kolonos Agoraios. North of it was built a small temple for the Mother of the gods, and, beyond that, another one for Apollo Patroös or the Ancestral Apollo. (Apollo was the father of Ion, the supposed ancestor of the Ionian Greeks, including the Athenians.) Further north was built a shrine for the principal god, Zeus, and beyond that, on the southern edge of the Panathenaic Way, the east-facing Royal Stoa or Stoa of the Basileus or ‘king’, one of three chief magistrates. (A stoa was a rectangular building with columns taking the place of one long wall, which offered shelter from rain or sun.) The Stoa of the Basileus was the earliest and smallest of the stoas to be built around the Agora.

In 480 and 479 Persian invaders destroyed or severely damaged all the buildings on the Akropolis and almost all those in the city below. They also carried off the statues of the tyrannicides. The Athenians did not rebuild the three shrines on the west side of the Agora, but secular buildings—the Stoa of the Basileus, the Council-house, the law court—were soon rebuilt. In 477 new statues of the tyrannicides were set up. In about 465 the Tholos or Round-house was built-on the south side of the Council-house as a dining-hall for the presiding committee of the Council. Because of its conical roof it was sometimes known as the Parasol. The most famous new building of the period was originally named after a kinsman of the distinguished general Kimon, son of Miltiades, but because of the painted panels that hung on its walls it became known as the Stoa Poikile or Painted Stoa. It stood on the north side of the Agora, facing south. So far only its west end has been excavated.

Kimon himself, after wresting Eion-on-Strymon from the Persians in 476, was allowed to set up three statues of Hermes on the north side of the Agora, which then or later were housed in another stoa, the Stoa of the Herms, somewhere between the Painted Stoa and the Stoa of the Basileus. (Hermes was the god of travellers and lucky finds and trickery, and images of him could be seen all over Athens and Attike. The head and phallos were rendered realistically, projecting from a rectangular shaft. The arms were mere stumps and the legs were not indicated.) Kimon also planted plane-trees in the Agora. More importantly, he brought back for burial from Skyros the supposed bones of the Athenian hero Theseus, but the Theseion which housed them has not yet been located.

Figure 6 The Agora c. 400 BC

Soon after the cessation of Athenian operations against Persia in 450, followed perhaps by the conclusion of a formal peace with Persia in 449, the Periklean building-programme got under way. This programme was primarily concerned with embellishing the Akropolis, and work already begun on a temple of the divine smith Hephaistos (the Hephaisteion) on Kolonos Agoraios was interrupted. There was, however, one new building completed, to the south-west of the Round-house, which may have been the headquarters of the board of ten generals, now the most important magistrates. In the last thirty years of the century there was a fresh spate of building in the Agora. In the northwest corner, on the site of the old shrine of Zeus, was built one new stoa—the elaborate Stoa of Zeus the Liberator (Eleutherios). Another, less impressive, new stoa was built on the south side of the Agora. It contained fifteen rooms, each of them containing seven dining-couches, and it may have been used by boards of magistrates concerned with the regulation of commerce. West of the old Council-house was built a new Council-house, and the old Council-house was freed for housing archives. Somewhere in the south-west corner of the Agora was built the first monument to the Eponymous Heroes, whose names had been given to the ten ‘tribes’ into which Kleisthenes had divided the citizen body. A new building in the south-east corner was probably the mint. In the north-east corner a courtroom was built.

There were also many important public buildings outside the Agora. To the south-east, above the south-east fountain-house and the mint but to the east of the Panathenaic Way, lay the Eleusinion, the precinct of Demeter and Kore, the goddesses whose Mysteries were celebrated at Eleusis. Further east lay the Prytaneion or Town Hall, which contained the communal hearth, a fire that was never allowed to go out, because it symbolised the continuing life of the community, and a dining-room where benefactors or guests of the city could be entertained. This was the symbolic centre of the city. Like the Theseion, it has not yet been located, nor has the Anakeion, the shrine of the Anakes or Dioskouroi— Kastor and Polydeukes.

We have already noted the circumstances in which the Pnyx became the regular meeting-place of the Assembly. For most of the fifth century the slope of the hill was exploited to make an almost natural theatre, with the speaker’s platform at the bottom facing the sea, and the citizens facing the Akropolis. There was sitting room (Aristophanes, Wasps 32, 43) for about 6,000. At the end of the century a huge embankment was raised inside a curved retaining wall and the natural arrangement reversed. Thereafter the assembled citizens were better sheltered from the wind.

Until the start of the fifth century dramatic contests were probably held in the Orkhestra in the Agora. When the wooden stands from which the spectators used to watch collapsed, it was decided to establish a permanent theatre in a more sheltered spot than the slope of the Pnyx, which faced north-east. The spot chosen lay on the southern slope of the Akropolis, above the small temple containing the wooden image of the wine god Dionysos Eleuthereus. Here, on a level terrace behind a retaining wall, the god had been honoured with singing and dancing since the introduction, by Peisistratos or his sons, of the cult of Dionysos of Eleutherai, a village on the northern frontier with Boiotia. Only a few blocks of the fifth-century theatre survive. It must have been a simple affair with rows of wooden benches overlooking the terrace, which accommodated a dancing area (orkhestra) for the chorus, a low stage for the actors and behind it a wooden stage building (skene). To the east of the theatre was built or rebuilt, at about the same time, the Odeion—the first roofed building in Athens used for concerts and musical contests. Its pyramidal roof rested on a nine-by-ten rectangle of ninety columns.

The main works in the Periklean building-programme were the new temple of Athena the Virgin (Parthenos) on the Akropolis, which we call the Parthenon, and the grand entrance to the Akropolis, the Propylaia. Work on the Parthenon, all in Pentelic marble, began in 447. The main structure of the Parthenon was completed by 438, when the cult image,

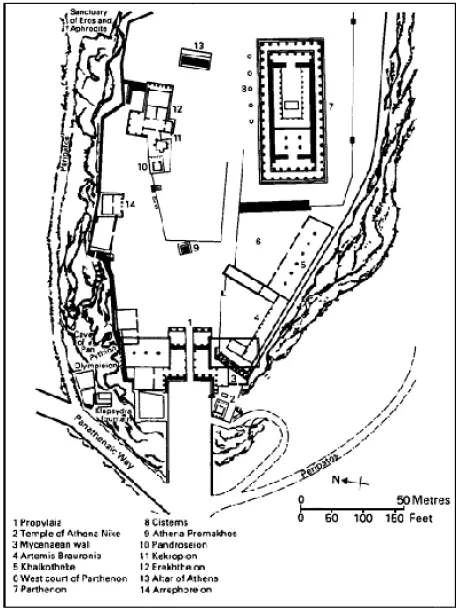

Figure 7 The Akropolis c. 400 BC

Pheidias’ colossal gold and ivory statue of Athena, was installed. The next year work began on the Propylaia, also all in marble, but was broken off after 432, because of the Peloponnesian War. A small temple of Athena Nike (Victory) on the south-west bastion of the Akropolis was built in the 420s. Work on the third great Akropolis building, the composite temple that we call the Erekhtheion, lasted from 421 to about 406. (Erekhtheus or Erikhthonios, a mythical king of Athens, was a son of Earth, reared ...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- CITY OF SOKRATES

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- FIGURES

- PREFACE

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- INTRODUCTION

- THE SOURCES OF KNOWLEDGE

- 1 COUNTRY AND TOWN

- 2 POPULATION, PROPERTY, TAXATION

- 3 RADICAL DEMOCRACY

- 4 THE IMPERIAL ETHOS

- 5 SCHOOLING, LITERACY, BOOKS AND HISTORY

- 6 RELIGION

- 7 ART AND PATRONAGE

- 8 SCIENCE, NATURE, CULTURE AND THE SOPHISTS

- 9 PHILOSOPHY, FROM ANAXAGORAS TO SOKRATES

- APPENDIX 1: ATHENIAN MONEY

- APPENDIX 2: CHRONOLOGICAL TABLE

- FURTHER READING