![]()

Chapter 1

Money

THE HISTORY OF COINAGE

A coin is a piece of money made of metal which conforms to a standard and bears a design. This book is concerned with the Greek tradition of coinage, which spread as far as India and Britain in antiquity. The earliest Indian coinage of the mid-fourth century BC may, or may not, have owed something to Greek inspiration through Persia, but in any case Indian coinage was certainly influenced by the Greek tradition from the third century BC (Cribb 1983). Chinese coinage, introduced a mere century or so after the Greek, was an entirely separate development, and thus is not considered here.

How can one justify calling the tradition Greek, when a reasonable case can be made that coins were first struck in the kingdom of Lydia? The primacy of Lydia should not be taken for granted. No great weight can be put on the fact that the earliest written source, a sixth-century writer (Xenophanes) quoted in a thesaurus of the second century AD, claimed that coinage was a Lydian invention (Pollux IX, 83). Even if the quotation is genuine, the claim need not be true (cf. Kraay 1976: 313). The case rests on the preponderance of Lydian coins in the earliest datable archaeological context for coinage, and the consideration that Lydia possessed the natural sources of electrum, the alloy of gold and silver from which the earliest coinage was made (Hdt. I, 93; V, 101). Against this it is perhaps worth emphasizing that the earliest archaeological context is in the Greek city of Ephesos.

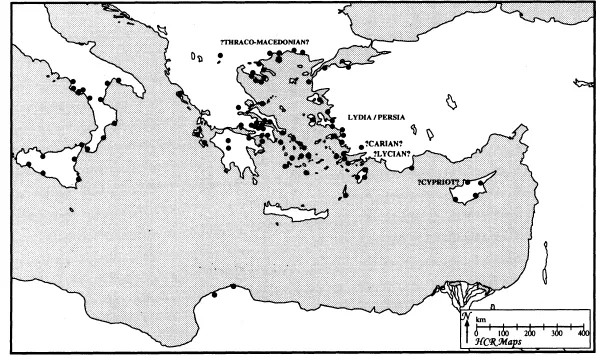

Wherever the earliest coins were actually struck, it is valid to interpret coinage as a Greek phenomenon. The most important reason is that coinage spread rapidly throughout the Greek world, but was slow to take root elsewhere. Within the Persian empire coinage was produced in the sixth century BC only in hellenized areas (western Asia Minor, Cyprus, Cyrene). The Phoenicians struck no coins until the middle of the fifth century. The Carthaginians produced their first coinage in Sicily in the second half of the fifth century. Etruscan coinage was plentiful only in the third century, although there were a few issues in the fifth and fourth.

The other reason is that Lydia, for all its political power, was itself under marked Greek influence (Boardman 1980: 97). Lydian art was thoroughly permeated by East Greek styles, and the Lydian capital at Sardis even had an agora (Hdt. V, 101; elusive to the archaeologist: Hanfmann 1983: 34, 69, 72–3). It would be dangerous to go too far in this direction. After all, the transformation of Sardis into a Greek polis, both physically and in terms of political institutions, did not take place until the third century BC (Sherwin-White and Kuhrt 1993: 181; Hanfmann 1983: 109–38). To claim coinage as a purely ‘Greek invention’ would be to miss the possibly important point that coinage developed where Lydian and Greek cultures interacted. Nevertheless, coinage soon became a Greek phenomenon. The Greek, or at any rate hellenized, context of the earliest coinages is important for understanding the historical significance of the introduction and spread of coinage (see pp. 14–18).

Renewed excavations of the Temple of Artemis at Ephesos have undermined older conclusions about the chronology of the earliest coins based upon the sequence of structures on the site (Bammer 1990; 1991). Now we can say only that the earliest context for electrum coinage is underneath the temple of c. 560 BC to which the Lydian king Croesus contributed. Arguments from art history and the date of the pot in which some of the coins were found (c. 650–625 BC) have been used to push the date of the beginning of coinage back well into the seventh century, but they cannot be conclusive (Weidauer 1975; Williams 1991–3). The style of coins may be conservative, comparison between large pots and tiny coins is problematic, and poor workmanship is easily mistaken for archaism. An old pot may contain more recent coins. In default of convincing new evidence it is better to emphasize the secure terminus ante quem of c. 560 BC, and to admit that we are not sure how much earlier coinage began.

The coins from underneath the Artemision of 560 BC were in the form of lumps of electrum made to a weight standard, some unmarked, some with just punch marks, some with striations on one side and punches on the other [3], and others with true designs and punches. The temptation to divine an evolutionary sequence is to be avoided (Price 1983). All are in the same archaeological context, and one typeless nugget was stamped with the same punch as a coin which has the design of a lion’s head on the other side (Karwiese 1991: 10).

We know nothing about the function of the earliest coinage. Theories that coins were first used to pay mercenaries, or for a wider range of standardized payments by and to the state, are consistent with the character and behaviour of the coinage (Cook 1958; Kraay 1976: 317–28). Literary and documentary evidence is, however, quite inadequate to allow us to decide between competing hypotheses.

We know remarkably little even about the authorities behind the issue of the earliest electrum coinages. The most common type of coin at the Artemision depicts a lion’s head (the smallest fractions have a lion’s paw) and sometimes bears an inscription [4–5]. A second inscription is known from a related issue not found at the Artemision [6]. All these coins are assumed to be Lydian because of their commonness and wide distribution (forty-five were found at the Phrygian capital of Gordion), and because the inscriptions are not in Greek. It has been generally accepted that the inscriptions, which may be transliterated as VALVEL and RKALIL, represent the names of individuals, but they may also be taken to refer to the mint (Carruba 1991). A related issue has confronted boars’ heads and an inscription (Bammer 1991: 67). Some other types have been associated with Greek cities; the most convincing example is the attribution of coins with a seal to Phocaea, where the seal (phōkē in Greek) became a standard part of the type [2].

Some scholars have been convinced that the earliest coins were produced by individuals rather than states (whether kingdoms or cities), partly because of the great variety of types (e.g. Furtwängler 1986; Price 1983). The same conclusion was once drawn for the same reason about the earliest (silver) coinage of Athens [e.g. 19]. This view cannot be disproved, but there is no certain case in the whole of antiquity of coins being produced by individuals. At some periods states produced coinages for individuals (see pp. 33–4), but that is an entirely different matter. Furthermore, it is easy to find examples of later state coinages with a multiplicity of types (Furtwangler 1982). Among the early electrum the large number of types gives a mistaken impression that there was also a large number of mints. In a number of cases different types share the same reverse punches, showing that they are likely to have been produced at the same place (Weidauer 1975).

The famous type which appears to have the inscription ‘I am the badge of Phanes’ adds some plausibility to the case that some coinages were personal [1]. However, the interpretation of the inscription has been challenged (Kastner 1986), and, even if Phanes is a personal name, we do not know who this Phanes was (might he have been a tyrant, or other kind of ruler, or a person responsible for a state coinage?; Furtwangler 1982: 23–4). One might argue that it is invalid to infer from the absence of later examples of personal coinages that the earliest coinages were not personal. The earliest coinages might in principle have been different. However, the spread of coinage does seem to make sense in the context of the development of the polis as state (see pp. 14–18), and the onus of proof is upon those who wish to argue that the earliest coinages were personal.

Electrum coinage was replaced in Lydia by a coinage in gold and silver, probably under Croesus (c. 561–547 BC), but possibly only under the Persians (547 BC onwards) (Carradice 1987a) [27–8]. The Persians continued to produce gold and silver coinage until the time of Alexander [29–30], but most Greek cities turned exclusively to silver. It is sometimes said that electrum was abandoned because the natural alloy contained varying amounts of gold and silver, and hence the value of any given coin was uncertain. This explanation may not be valid, because analyses have now shown that the alloy of some of the Lydian electrum coins was controlled (Cowell et al. forthcoming). Thus it may be significant that there is archaeological evidence for the separation of gold and silver at Sardis c. 620–550 BC (Hanfmann 1983: 34–41; Waldbaum 1983: 6–7). Major electrum coinages of controlled composition were produced at Cyzicus [32], Mytilene, and Phocaea until the fourth century BC.

Outside western Asia Minor the chronology of the spread of coinage is highly uncertain. For the sixth century there is only one datable archaeological context, namely the foundation deposits under the Apadana at Persepolis.1 To this evidence may be added the reasonable suppositions that the greater part of the substantial coinage of Sybaris in south Italy was produced before the city was destroyed in 510 BC [12], and that the coinages of some of the later colonies were not struck until after the cities were founded (for example Abdera in c. 544 BC, and Velia in c. 535 BC) [25; 11]. There are perhaps no other secure chronological pegs for dating coinage in the sixth century. Archaeological fixed-points, or more usually termini ante quos, multiply from the early fifth century. Careful analyses of hoards which contain coins from different mints allow chronological conclusions about the coinage of one city to be extended to coins struck elsewhere. Thus we can be reasonably confident of the stage reached by many coinages by the early fifth century. Estimates of how long it took to produce the coins struck before that stage are used to establish the date of the start of the various coinages. This is really guesswork, and unwarranted precision is a great danger to the subject.

Figure 1 Approximate spread of minting up to 500 BC; some attributions are uncertian, and chronologies are often doubtful (Map courtesy of Henry Kim)

Such agnosticism should not be allowed to detract from an important perspective. Arguments from silence are always dangerous, but the paucity of early archaeological contexts for coinage is striking. New evidence may bring surprises, but at the moment there is little reason (apart from later literary references) to push the start of silver coinages back much before the middle of the sixth century. This means that the spread of coinage throughout the Greek world was rapid. By 500 BC there were established coinages in mainland Greece, Italy, Sicily, and the hellenized areas of the Persian empire (including Cyrenaica) (Fig. 1).

In a few cases the diaspora of East Greeks in the face of Persian pressure allows the process of the spread of coinage to be traced. Abdera, founded c. 544 BC from Teos, adopted the same coin type as its mother city, but differentiated its coinage by showing the griffin facing in the opposite direction [25 cf. 9]. Velia was founded by Phocaean refugees c. 535 BC; it adopted a style of coinage familiar from the homeland and quite unlike the incuse coinage of the other Greek cities in south Italy [11]. Samians who fled to Zancle in Sicily after the Ionian Revolt struck coins showing the lion scalp from the statue of Hera on Samos and, on the other side, a Samian galley [13]. The East Greek diaspora, ties between mother-city and colony, and trade all provided mechanisms for the spread of coinage, but the rapidity of the spread is better explained by the economic, political, and social transformation of the Greek polis which made the Greek world ripe for coinage (see pp. 14–18).

Considerations of the function of early Greek coinage must take into account the range of denominations available. It has been argued that the minimal supply of low denominations in all but a few states means that coinage was of little use in a retail context (Kraay 1964). This observation does not take into account the fact that market exchange was itself undergoing a process of development at the time of the introduction of coinage (see pp. 16–17), and the factual base of the claim has also shifted. Metal detectors and greater scholarly awareness have increased our estimate of the incidence of fractional coinage.

Kraay properly observed that the high value of electrum means that even the smallest electrum coin was still worth something like a day’s wage (he did not mean to imply anything about the existence of wage labour in sixth-century western Asia Minor). There is another perspective. The smallest electrum denomination, one ninety-sixth of a stater, weighs c. 0.15g [7]. The smallest Athenian silver fraction so far discovered is one sixteenth of an obol, and weighs a staggering 0.044g (Pászthory 1979). Thus in some contexts coins were made just as small as possible (it is very hard to imagine how coins as small as this were actually handled).

That issues of fractional coinage in the archaic period might be substantial may be illustrated by one example. A sixth-century hoard from western Asia Minor contains 906 silver coins of the same type, in three denominations (CH I, 3; Kim 1994) [8]. The two smallest denominations average c. 0.43g and c. 0.21g, and were struck using nearly four hundred known obverse dies. This suggests an original production of at least several million coins, and much higher figures are possible (cf pp. 30–3). By any standards that is a large issue. Ionia was a region which enjoyed a relatively good supply of fractional silver, and in this respect continued the traditions of the electrum coinage. A single instance is no substitute for a much-needed survey of the incidence of fractional coinage throughout the Greek world (cf. Kim 1994). Even so, this one example is sufficient to show that a significant supply of fractions need not be predicated upon the kind of widespread state pay seen in democratic Athens (cc pp. 18–19).

Thus it now appears that the quantity of fractional coinage in the late sixth and fifth centuries was greater than was thought a few decades ago, but it would be quite wrong to give the impression that a good supply of fractional coinage was ubiquitous in the Greek world. The development of a token base metal coinage for small denominations remains an important watershed. The low value of base metal (usually bronze) meant that even small denominations were large enough to handle without undue difficulty. There was a north Etruscan tradition of using base metal by weight as a form of money, which on archaeological evidence went back at least to the sixth century BC. This tradition was continued by the Romans in a modified form until the Second Punic War (see p. 112). Elsewhere bronze was a token coinage from the first (Price 1968; Picard 1989). This may help to account for the opposition to its introduction, which is recorded at Athens in the fifth century BC (Athenaeus XV, 669 D), and may be inferred from penalties in a law about the introduction of bronze coinage from Gortyn in the middle or second half of the third century BC (Syll.3 525; Austin 1981: 185–6, no. 105).

Athens adopted a regular bronze coinage only in the third quarter of the fourth century BC (Kroll 1979) [24]. Elsewhere in mainland Greece the coinage of Archelaus I of Macedon shows that a bronze coinage had been introduced by the end of the fifth century, and excavations at Olynthos (destroyed in 348 BC) demonstrate that it was a widespread phenomenon by the middle of the fourth century. The bronze coinages of some cities in south Italy and Sicily began earlier. Those of Thurium and Acragas, at least, started before 425 BC (Price 1968; 1979b). A separate development from base metal money in the form of arrowheads, through wheel money and dolphins, to round coins took place in the region to the north and west of the Black Sea between the mid-sixth and mid-fourth centuries BC (Stancomb 1993).

At the other end of the denominational scale Persian gold darics [30], Lampsacene gold, and Cyzicene electrum [32] were used as ‘international’ currencies until the time of Alexander. Indeed, electrum seems to have become a standard coinage for the Black Sea region. An international role was taken on by the gold coinage produced in the name of Philip II of Macedon [43]. The role of ‘Macedonian’ gold was greatly extended under Alexander, who struck gold throughout his empire as far east as Susa [44]. Gold coinages continued to be produced extensively in his name until c. 280 BC, but later became confined to the Black Sea area and western Asia Minor, and ended by c. 200 BC (Price 1991a). Some of the successor kings produced gold coinages in their own names, but one gets the impression t...