- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Managing Aggression

About this book

How to manage and respond to escalating violence towards staff working in the human services is a pressing professional problem. This workbook:

- empowers individuals by providing a range of useful useful skills that can help in managing aggression

- enables staff placed in difficult or dangerous situations by their employers to address the issue effectively

- clarifies the responsibilities of the manager in ensuring staff are safeguarded

- builds confidence in staff and their managers by offering workable solutions to reducing levels of aggression in the workplace.

Highlighting examples of good and bad practice, Managing Aggression is a book for anyone who has ever faced, or is likely to face, aggression at work.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

MedicineSubtopic

Health Care DeliveryCHAPTER 1

WORKPLACE CULTURE

This chapter considers different workplace cultures and their potential to affect the level of aggression experienced by staff. It will examine reasons why certain cultures are prevalent within social care and it will give the reader the opportunity to identify the culture that operates around them at work. The way that public opinion heightens the problems experienced in the work setting is also examined. Finally, measures that have brought about effective change in workplace cultures are identified to provide a suggested plan of action.

OBJECTIVES

By the end of this chapter you should:

- Have a clearer understanding of what the term ‘violence’ actually means within the workplace.

- Be aware of some of the negative cultures that are all too commonplace within social care.

- Have considered the element of ‘zero tolerance’ to aggression at work.

- Be able appropriately to challenge preconceived notions that aggression is ‘a part of the job’.

- Identify ways of improving the public image of social care.

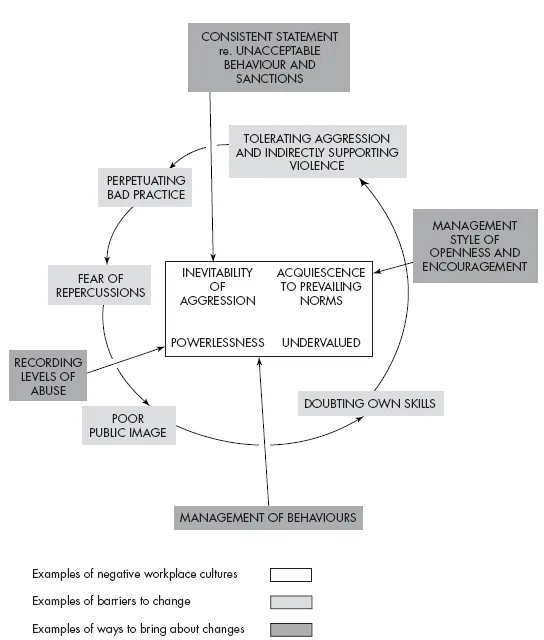

Figure 1.1 illustrates the points to be made and their interrelationship. Taking the workplace culture as the starting point, negative associations such as viewing aggression as inevitable become one of the barriers to effecting change. Bad practice may then be reinforced in a way that indirectly supports the continuation of violence; whereas strategies such as recording levels of abuse and clarity regarding sanctions break this circle.

Figure 1.1 Workplace culture

THE CULTURE OF INEVITABILITY

At the start of any training course I usually pose the question: ‘Have you experienced aggression within your work?’ At this stage many of the participants may not actually know what ‘aggression’ is. Some people think that aggression is purely physical, others that it involves either being purposefully damaged by another person or persons or having their lives put at risk. Some people think that an act is not really an aggressive act if it comes from someone who cannot understand what they are doing. Others think that ‘they’ (service users) have to do it as a means of expressing their frustration, and so, whatever the ‘it’ is, it is not categorised as aggression, even when this means that staff experience being scratched, pinched, spat at and so forth.

CONSIDER your workplace and the term ‘aggression’.

Is there a certain level of aggression that staff are expected to tolerate? If so, why?

In order to attempt to focus course participants’ thinking I prompt: ‘I think you know when that line has been crossed. I think you know when you have experienced aggression.’ With this, usually between 80 and 100 per cent of participants answer ‘Yes’ to the question. Occasionally, however, one or two of the participants do not answer in the affirmative and for a brief moment my heart soars and, somewhat like the Heineken ad, I think ‘How refreshing’. The moment does not last long, however, as the realisation of the answer that has been given sinks in. Instead of ‘No’ the typical alternative response is ‘Not yet’. At this stage the group exchange knowing looks, a few people smile, perhaps remembering a time when they were new to the job before they had experienced aggression. One or two may even laugh and offer words of supposed comfort or encouragement, like ‘Give it time’, to which the veterans in the group nod.

This culture of inevitability is endemic within some agencies and it is one that must be challenged and changed, otherwise it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. It is also probably a contributory ingredient to the fact that social care staff have the lead position in being the most abused profession as compared to any other comparable working group.1

ACTIVITY 1.1

In a group discuss:

Does your workplace have a culture of inevitability that aggression will occur?

No one is paid to be abused (verbally or otherwise), threatened, intimidated, shouted at, harassed, assaulted or murdered. Thankfully the murders are rare, yet the death of Jenny Morrison, a qualified, experienced and skilled worker, in November 1998 at the hands of a service user, plus the deaths of seven other social care staff since 1984, prove the risk is always with us. Aggression is not a part of the job and any workplace culture that implies that it is, is wrong.

ACTIVITY 1.2

In a group, brainstorm (or discuss):

- In order to bring a halt to the ‘culture of inevitability’ what is required within my workplace is . . .

- This can be achieved by . . .

Often new employees ‘slot in’ to the existing workplace culture and practices, accepting the ‘norms’ operating around them as good or at least standard practice for working with ‘this client group’. Sometimes this may involve perpetuating approaches, attitudes and systems that are harmful to the service user. A clear example of this was identified in the MacIntire exposé shown on national television in November 1999. In this programme potentially harmful methods of physical intervention were identified as commonplace and regularly used within a residential establishment caring for people with learning difficulties. This was, it must be stressed, contrary to both the advice given by the Department of Health (DOH) concerning physical restraint and to good practice. The advice given by the DOH at that time emphasised that physical restraint was to be used as a last resort and must not become a regular feature of practice.2

Many of the staff who were filmed in the exposé would no doubt consider as wrong a regime that made use of the regular imposition of physical force as a means of achieving compliance by the service user, especially if such a regime were to be applied to them. Yet it was the staff in the unit who were the ones who perpetuated the regime, and new staff at best acquiesced and at worst became a part of the regime which considered frequent physical intervention to be ‘acceptable practice’ for this group of service users.

Why would staff go along with, or become part of such a regime?

This was an extreme case and, with the advent of the Public Interest Disclosure Act (1998) and the new regulations that came out in July 1999 safeguarding the whistle blower, the ‘cover-up culture’ should be a thing of the past. (Points regarding the Public Interest Disclosure Act are included at the end of this chapter.) However, at a less extreme level the experience of going along with the prevalent culture is not uncommon. Often we are clear in our private lives about what is and what is not acceptable behaviour. Yet this clarity is somehow changed, or lost, when it comes to the level of aggressive behaviour we will tolerate at work. At home, for instance, if someone were to tell us to ‘fuck off ’, generally the majority of us would regard that as unacceptable and we would probably do something about it. However, when we first walk into a new job, although we may initially be shocked at the levels of abusive language and behaviour prevalent, how many of us look around and, because other staff members are putting up with it, think to ourselves, ‘That must be what I’m expected to put up with around here’? In effect, we adapt to the implied negative workplace culture of acceptability and inevitability – rather than the positive one of ‘This behaviour is unacceptable and it requires me and my colleagues to work with it in order to change it where possible.’

In order to bring about effective change to the culture of acquiescence all team members must have a clear starting point concerning the level of behaviour that they feel is acceptable and that which is unacceptable. Once behaviour is identified as unacceptable it becomes possible to manage, or attempt to manage, consistently.

STRATEGY: DEFINING ‘VIOLENCE’

ACTIVITY 1.3

In a group of four to five people:

- Make a brainstormed list of the Negative Words and/or Negative Behaviours you have experienced while doing your job. Please be specific when you describe the behaviour and words but do not, at this stage, give any information about the circumstances, or the age, gender or state of the person who behaved in this way.

- Next, still in your group, think about the impact this behaviour or this word had upon you and write it down alongside. Think about the impact from three positions:

- How did you feel at the time?

- Did the situation have an impact upon your home life (irritability, inability to sleep, etc.)?

- Is there an ongoing impact of desensitisation?

Your list may now look something like this:

See Table

- Now for the third and often hardest part of the exercise. Think of the individual circumstances. Think of the person whose behaviour you described. Think about what was going on in their life at the time they exhibited this behaviour. What was your part in this situation? What did you do, or say?

While you are thinking about the individual circumstances, AS A GROUP IDENTIFY (by placing a tick alongside) ANY of the above behaviours and/or words that the group considers to be ACCEPTABLE.

So if for example you think being ‘spat at’ is acceptable, perhaps because of the circumstances or condition of the person doing it, place a tick alongside that behaviour.

During this part of the exercise please discuss the difference between ACCEPTABLE and UNDERSTANDABLE behaviour. - Once this is completed, identify any of the behaviours that have been ticked. If there are any, identify the impact that the negative word or behaviour had upon the person concerned.

- Now discuss:

- Is it acceptable for behaviour to damage another individual?

- If we do not address negative behaviour, what message are we giving to the person who is exhibiting that behaviour?

- What message are we giving to the other service users who may witness such behaviour?

We can see from the above that there is a difference between UNDERSTANDABLE and ACCEPTABLE behaviour and, whilst it remains fundamentally important to retain the quality of understanding, workers must not allow this quality of understanding to impair perception. Words or behaviours that damage another human being are simply UNACCEPTABLE and as such must be managed and not tolerated. If tolerated, the message provided to the service user is ‘please continue’. Furthermore the message given to other service users who may witness the behaviour is equally negative.

It has long been recognised that individuals are unique and what may damage one may have no effect upon another. Individuals can be damaged by a word as well as a deed. This recognition was highlighted in 1992 when the Association of Directors of Social Services identified violence as: ‘Behaviour which produces damaging or hurtful effects physically or emotionally on other people.’

This definition does not limit violence to merely a physical injury. It states that the victim may be damaged emotionally, i.e. experience ‘hurtful effects’. However, the hardest part of this definition for any of us to own up to, to identify and to report is the emotional impact that dealing with this behaviour may have generated within us.

ACTIVITY 1.4

Individually or within a group, brainstorm:

Why is being damaged emotionally the hardest part for any of us to report?

The reasons given for not reporting the emotional impacts often include:

‘. . . viewed as a sign of weakness . . . my colleagues seem to put up with it so I think I should be able to . . . it’s personal and I don’t want my colleagues to know that I’m affected. . . . I don’t want people to think I can’t cope. . . . I want to preserve my self-image that I can manage . . . we’re not...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Figures

- Case Studies

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Workplace Culture

- Chapter 2: Causes of Aggression

- Chapter 3: Assessing Risk

- Chapter 4: Organisational Responses to Violence Towards Staff

- Chapter 5: Managing Aggression

- Chapter 6: Bullying at Work

- Chapter 7: Ethnic and Gender Issues

- Chapter 8: The Consequences of Aggression

- Chapter 9: Alternatives to Aggression

- Bibliography

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Managing Aggression by Ray Braithwaite in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Health Care Delivery. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.