![]()

1

Athens and Piraeus

1 Athens: a historical overview

The modern visitor sees Athens as an impenetrable expanse of monotonous concrete buildings which fills the entire basin lying between the mountain ranges of Aigaleo in the west, Parnes and Pentelikon in the north, Hymettos in the east and the sea in the south. In fact Athens consists of many municipalities, each one with its own name, which have only grown together in the last decades to turn it into a large city. By the name ‘Athens’ the Greeks themselves understand only the quarter around the Acropolis, especially the area north of the ancient citadel.

The reasons for the growth of this huge concrete desert are easily described. Athens was a small town until 1834, when it became the capital of the Kingdom of Greece (Plates 1, 2, 5, 18). Then it grew in several stages into a city of millions. After the influx of 1922, when many Greeks had to leave their cities on the west coast of Asia Minor, there were already about half a million inhabitants. Since World War II, especially since the early 1960s, the populace has left the countryside in ever-growing numbers and come into the cities from the villages and the islands. Farming areas are desolate and only elderly people remain in the villages; in contrast the huge cities are facing lack of accommodation, structural chaos and air and sea pollution, as well as a shortage of water. This is particularly true of the largest Greek city, the Greater Athens area, which is inhabited by about four million people today, about 40 per cent of the population of the entire country.

A ‘concrete desert’? This is certainly not what the visitor to Athens expects, and it is indeed only a first impression. For the rugged hill of the Acropolis, visible for miles, rises out of the amorphous mass of the modern capital and immediately conjures up the ruins of antiquity; these can be seen in many different forms on this citadel and around it; their presence illustrates the importance of Athens for the history of the art and culture of Europe and the Western civilisations. Moreover, the visitor can find much of interest on his walk amidst all the modern city buildings, which in some areas have recently been turned into welcome pedestrian zones: charming Byzantine churches (Plate 11) or Neoclassical houses and villas of architectural interest (Plate 28) and also the old town, Plaka, with its narrow alleys and noisy businesses and craftshops (Plate 22). The topography of the capital is also impressive with its mountain ranges and isolated hills from which the visitor can obtain a good view over the sea of buildings to the edge of the basin of Greater Athens and over the Saronic Gulf with its islands of Aigina and Salamis.

It was the geographical advantages which drew the first prehistoric settlers here, such as the favourable trading locality near the sea, the fertile plain and the hills which offered safe refuges. This type of landscape has given rise to settlement centres all round the Mediterranean; it can be seen constantly in Greek settlements, whether in Greece itself or in Greek colonies elsewhere, such as Nice and Marseilles.

On the rock of the Acropolis, the steepest hill on the plain, there are traces of a settlement dating back to Neolithic times, that is 4000–3000 BC. The first datable building remains belong to the Mycenaean period, when the citadel was enclosed by a massive fortification wall and sheltered the king’s palace. From the eleventh to the eighth century BC the entire social structure of Greece was disrupted by the arrival of pastoral tribes from the north; during this time – the so-called Dark Ages – Attica, like the rest of Greece, was a victim of these disturbances (there seems to have been no continuity of culture in Athens). A new social order did not arise until the eighth century. Thereafter, noble families ruled the city-state and the citadel became a cult centre gradually losing its status as the seat of the ruler. Thanks to ancient historiography the most important developments of Greek history can be closely followed from now on. They are described briefly below with particular reference to Athens and to her role as the leader in Attica.

At the end of the seventh century law and order was established by the rigid law code of Drakon (624 BC), which was reformed by Solon (594 BC) and transformed into a first constitution. The result was the division of the populace into classes according to the land they possessed. Between 560 and 510 BC the Peisistratids, a noble family from Brauron, ruled in Athens as ‘Tyrants’ (= single ruler, not pejorative) and the city blossomed culturally. After the expulsion of the last son of Peisistratos, Kleisthenes reformed the constitution of Solon in 508/507 BC and thereby paved the way for the first democracy. Attica was divided into three units (Trittys) from which groups of three geographically separate units formed a tribe (Phyle). There were ten tribes, each being composed of many boroughs (Demes). Each tribe chose a leader (Strategos) and fifty councillors (Bouleutes). The chairman of the council which ruled Attica changed ten times a year. Ostracism was established – perhaps under Kleisthenes or a bit later – to counter the threat of a single politician seizing absolute power; a person with too much power could be banished for ten years on the vote of the Assembly of the people. The voting slips were sherds from broken pots (ostraka) on which the name of the candidate for banishment was scratched.

The following decades were dominated by the Persian Wars. In 490 BC the Athenians and the Plataians defeated the Persian army at the Battle of Marathon; ten years later in 480 BC a Greek fleet composed of swift, manoeuvrable triremes defeated the Persians in the naval Battle of Salamis. Shortly beforehand, the Spartans under King Leonidas had tried in vain to hold the Persian forces at the Battle of Thermopylae; a year later at the Battle of Plataia the Greeks finally defeated the Persians. Athens, the real victor of the Persian wars, founded the naval Confederacy of Delos (the Delian League) in 477 BC as a defensive alliance against the Persians; at first the members had to supply ships, but later this was commuted to paying tribute to the treasury, which was moved to Athens in 454 BC from the Sanctuary of Apollo on Delos. The profits from this and from the silver mines at Laurion provided the financial foundation for the golden age of Athens after 460 BC under the leadership of Perikles (c. 500–427 BC). During this golden age the famous temples on the Acropolis and in Attica were built and ‘Classical’ art was born, as manifested in sculpture and painting (the latter known almost only from its reflection in vase painting). Athens with its democracy set itself politically even more strongly against the aristocratically-ruled city-states led by Sparta. The conflict for the supremacy of Greece peaked in the Peloponnesian War 431–404 BC from which Sparta emerged as the victor. It set up the ‘Thirty Tyrants’ as rulers in Athens. At the end of the fifth century BC the Tyrants tried but failed to destroy the democracy in Athens together with its supporters. In the fourth century BC the rivalry between Sparta, Thebes and Athens determined the course of history; the country was shaken by many conflicts with shifting alliances between the Greek city-states. Philip II of Macedon recognised the weaknesses of the city-states and won supreme rule in Greece at the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BC. After his murder in 336 BC, his son Alexander the Great ruled until 323 BC and extended his empire by warfare into the east as far as India and into the south as far as Egypt. However, after his death his empire collapsed; his successors (Diadochs) divided it into many kingdoms which were in a state of constant conflict. During the Hellenistic Age 323–146 BC until the time of the Roman Empire, large numbers of new political and cultural centres evolved in the eastern Mediterranean in addition to Athens. Athens survived on its past glory under different rulers; the city was adorned with generous gifts from the Hellenistic kings as a tribute to the ‘Classical Ideal’. In spite of Greek resistance to the new might of Rome, Greece became the Roman province of Macedonia and Achaia in 146 BC. The new rulers were much influenced by Greek culture, which, especially under the Roman emperors, spread over the whole of the Mediterranean. Athens was especially friendly to Rome until it abruptly changed sides in 88 BC and was sacked therefore by Sulla in 86; Piraeus was burned and never really recovered until the twentieth century. Numerous Roman politicians studied at the famous schools of philosophy and rhetoric in Athens and some of the Caesars also had contacts with Greece, especially with Athens; in the arts Greek ideas, decorative schemes and other ornamental elements were taken over and reproduced in a Roman style. Roman rulers, especially Pompey, Caesar, Augustus, Nero, Hadrian and Marcus Aurelius showed their respect to Athens by gifts of buildings and monuments, as well as by visits, during which they could see themselves as successors to the great men of Greek history. Wealthy private citizens, such as Herodes Atticus (second century AD), followed their example. The beginning of the collapse of the Roman Empire undermined the influence of Athens as an intellectual centre, and the invasion of the German tribe of the Herulians in the mid-third century AD played a decisive role in the decline of the city. From this time on defensive constructions are almost the only things of interest; these were, however, built from earlier ruined or collapsed buildings. Under Constantine the Great, Christianity was proclaimed as the state religion in 312 AD and the capital of the Roman Empire moved to Constantinople. The heathen schools of philosophy and the temples were closed under Theodosius (379–395 AD) and Justinian (527–565 AD). New excavations south of the Acropolis provide some information about building activity during the seventh century AD, but the city then sank into an obscurity which lasted for centuries.

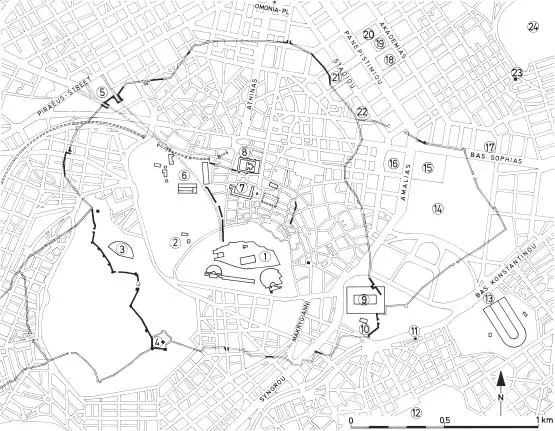

Figure 2 Map of the historical centre of Athens with the important ancient monuments.

1: Acropolis; 2: Areopagos; 3: Pnyx; 4: mausoleum of Philopappos; 5: Kerameikos; 6: Agora; 7: Roman market; 8: library of Hadrian; 9: Olympieion; 10: Ilissos area; 11: Temple by the Ilissos; 12: First Cemetery; 13: stadium of Herodes Atticus; 14: National Garden; 15: Palace (Parliament);16: Syntagma (Constitution) Square; 17: Benaki Museum; 18: Akademy; 19: University; 20: National Library; 21: Ay. Theodoroi; 22: Old Parliament; 23: Hadrianic water reservoir; 24: Lykabettos.

Greece became the stamping ground of foreign powers. In the thirteenth century the Frankish crusaders divided the country. In 1456 Athens was taken over by the Turks, who allowed the land to go to waste in the following centuries during their continual struggles with the Venetians. Their rule was finally broken during the War of Independence (1821–1830) with the help of the great powers, France, Great Britain and Russia. According to a decision of the powers in London, with which the National Assembly of Greece agreed, Wittelsbach Prince Otto, son of Ludwig I of Bavaria, became King Otto I of Greece. Athens, which at that time comprised about 300 households, became the capital in 1834. In 1830 the first systematic investigation of the ancient monuments began and a new city (Figure 2) was designed by Bavarian and Prussian architects (Klenze, Schinkel, Ziller, the Danish brothers Hansen amongst others) and carried out following Neoclassical models (Plates 2, 28). In the 1912–13 Balkan Wars Greece gained Epirus, parts of Macedonia, Crete and Samos as part of its territory. In 1922 after a Greek invasion against Turkey about 1.6 million Greeks had to abandon Asia Minor and flee to Greece. In World War II the country was occupied by the Italians and the Germans, but gained the Dodecanese at Liberation. In 1967 a military junta abolished the constitutional monarchy under King Constantine II and in 1973 it proclaimed a republic. On 25 November 1973 the dictator, George Papadopoulos, was removed. In 1974–75 democracy was re-established under President K. Karamanlis and the constitution of the junta was abolished, though Greece remained a republic. In 1981 Greece entered the European Union; the socialists under A. Papandreou ruled until 1989, followed by a Conservative government under K. Mitsotakis, which was replaced in its turn in 1993 by another socialist government (A. Papandreou, K. Simitis).

2 The Acropolis (Figure 5.6)

At the time of the earliest settlement in Attica the hill of the Acropolis did not look as it does today; without the high retaining walls on its south, east and north sides, it did not appear nearly so precipitous in spite of its steep slopes. The area on the top of the rock was smaller and not so level, since the citadel had not yet been planed and filling and terracing had not yet taken place. The rock probably still had a layer of earth covered with scrub amongst which were placed the simple huts of the Neolithic inhabitants. Pot sherds found in crevices in the rock provide evidence for this phase of the settlement.2

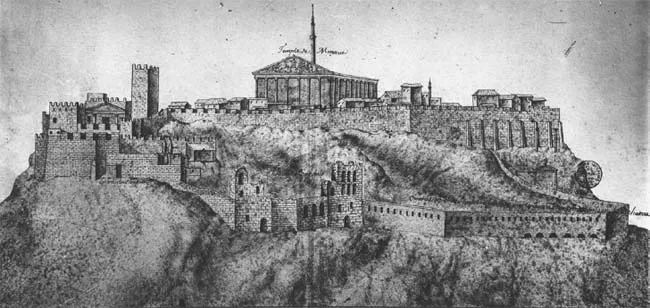

Figure 3 The Acropolis from the south-west (Nointel and d'Ortières 1674/1678).

Photo DAI Athens (Akr 436)

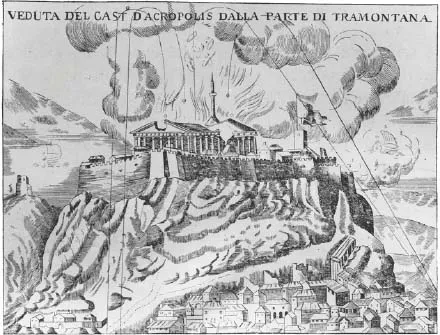

Figure 4 Explosion on the Acropolis, 27 September, 1687: view from the north-east.

(F. Fanelli, Atene – Attica 1707, 64)

The first real architecture, of which remains can be seen even today, dates from the Mycenaean period.3 At this time the Acropolis was the site of a palace which, according to mythology, belonged to the Kings Erechtheus and...