![]()

1 | Introduction |

| | Some basic concepts and stylised facts and the case for (and against) floating exchange rates |

In this book we attempt to produce a coherent overview of the main theoretical and empirical strands in the economics of exchange rate literature and in this chapter we try to set the scene for the rest of the book. Rather than give a blow-by-blow account of succeeding chapters, whose titles listed in the contents page give a firm indication of their contents, we here present some salient issues and a number of important stylised facts which we believe will motivate and set-up the following chapters. In thinking about exchange rate issues, it has become increasingly fashionable in the exchange rate literature to take a microstructural approach to the foreign exchange market (see, for example, Lyons 2001). This approach is very interesting and greatly enhances our understanding of how the main players in the foreign exchange market interact and drive exchange rates, and we consider this approach in some detail in Chapter 14. However, the main theme in this book is that macro-fundamentals are important for explaining exchange rate behaviour and we argue at various points in the book that a macro-fundamental approach can explain the main puzzles in the exchange rate literature.

In the next section we outline some basic definitions of spot and forward exchange rates and we then go on in Sections 1.2 and 1.3 to discuss the main players in the foreign exchange market and the kind of foreign exchange turnover they generate. In Section 1.4 we consider some monetary and balance of payments accounting conditions, under fixed and floating exchange rates, and then go on in Section 1.5 to examine the traditional balance of payments approach to the determination of the exchange rate. In Section 1.6 the covered interest rate parity condition is considered against the backdrop of the Tsiang (1959) analysis of the determination of spot and forward exchange rates, and the related uncovered and closed interest parity conditions are discussed in Section 1.7.

In Section 1.8 we introduce some key stylised facts of the foreign exchange market, namely, the issues of exchange rate volatility – specifically issues of intra- and inter-regime volatility – and the apparent randomness of exchange rate behaviour. These are themes we shall return to on a number of occasions throughout this book and indeed are at the heart of the debate between those economists who favour a macro-fundamentalist approach to exchange rate determination and those who favour a market microstrucure approach.

Although the textbook exposition of, say, the operation of monetary and fiscal policy in an open economy often portrays this in the context of the polar cases of fixed versus floating exchange rates, there are a large range of intermediate regimes between the extremes of fully flexible and rigidly fixed exchange rates and these are considered in Section 1.9, along with some practical issues relating to the measurement of exchange rate regimes.

The advantages and disadvantages of fixed versus flexible exchange rates are considered in Section 1.10, along with some discussion of the empirical evidence on the historical performance of the two kinds of regimes. In Section 1.11 we have a discussion of the determinants of exchange rate regimes while Section 1.12 focusses on currency invoicing practices.

1.1 Exchange rate definitions

There are two types of nominal exchange rates used extensively throughout this book, namely, the spot and forward exchange rate. The bilateral spot exchange rate, S, is the rate at which foreign exchange can be bought and sold for immediate delivery, conventionally 1 or 2 days. The bilateral forward rate, F, is that rate negotiated today (time t) at which foreign exchange can be bought and sold for delivery some time in the future (when a variable appears without a time subscript it is implicitly assumed that it is a period-t variable). The most popularly traded forward contract has a maturity of 90 days and contracts beyond 1 year are relatively scarce. Forward contracts are generally negotiated between an individual – for example, a private customer or commercial organisation – and a bank and the individual has to take delivery of the contract on the specified date. Futures contracts, which are also rates negotiated in the current period for delivery in the future, differ from forward contracts in that they are bought and sold on an organised exchange and the individual holding the contract does not need to take delivery of the underlying asset (it can be bought or sold on the exchange before the delivery date on the exchange). Futures rates are hardly addressed in this book. In general, throughout the book we define nominal exchange rates as home currency price of a unit of foreign exchange. This definition has been chosen since it is the most widely used in the exchange rate literature. It implies that an increase in the exchange rate (a rise in the price of foreign currency) represents a depreciation and a decrease in the exchange rate represents an appreciation. As we shall see, when considering effective exchange rates (both real and nominal), and sometimes for real bilateral rates, the convention is the opposite – a rise in an effective exchange rate represents an appreciation. In general, lower case letters denote the natural logarithm of a variable and so s = ln S and f = ln F.

These measures of the exchange rate are nominal. A real exchange rate is measured by adjusting the nominal exchange rate by relative prices. For example, the real exchange rate, Q, derived from adjusting the bilateral nominal exchange rate is:

or in natural logs:

where P denotes the price level in the home country, * denotes a foreign magnitude and lower case letter denote log values.

All of the earlier exchange rate measures are bilateral in nature – the home currency price of one unit of foreign currency (e.g. Japanese yen against US dollars). There are a number of exchange rates which define the home currency against a basket of foreign currencies and these are usually used when trying to obtain an overall measure of a country’s external competitiveness, and especially when relating exchange rates to international trade balances. A nominal effective exchange rate (NEER) in essence sums all of a country’s bilateral exchange rates using trade weights (NEER =

where

α denotes a trade weight,

i represents a bilateral paring and, in this context,

S is defined as the foreign currency price of a unit of home currency) and these are expressed as an index. With effective exchange rates, the convention is that a rise above 100 represents an exchange rate appreciation, while a fall below 100 represents a depreciation. As in expression (1.1), for the real bilateral exchange rate, a real effective exchange rate (REER) adjusts the NEER by the appropriate composite ‘foreign’ price level and deflates by the home price level, (REER =

, where again

S is the foreign currency price of a unit of home currency and

j represents the home country).

1 A multilateral exchange rate model (MERM), as constructed by the IMF, incorporates trade elasticities, in addition to trade weights, into the calculation of a real effective exchange rate. The idea here is that it is not just the size of trade between two countries that matters, it is also how responsive trade is between two countries with respect to the exchange rate.

1.2 The players in the foreign exchange market

The foreign exchange market differs from some other financial markets in having a role for three types of trade: interbank trade, which accounts for the majority – between 60% and 80% – of foreign exchange trade; trade conducted through brokers (which accounts for between 15% and 35% of trade); and trade undertaken by private customers (e.g. corporate trade), which makes up around 5% of trade in the foreign exchange market. The latter group have to make their transactions through banks since their credit-worthiness cannot be detected by brokers.

The agents within banks who conduct trade are referred to as market makers, so-called because they make a market in one or more currencies by providing bid and ask spreads for the currencies. The market makers can trade for their own account (i.e. go long or short in a currency) or on behalf of a client, a term which encompasses an array of players from central banks, to financial firms and traders involved in international trade. A foreign exchange broker on the other hand does not trade on her own behalf but keeps a book of market makers limit orders (orders to buy/sell a specified quantity of foreign exchange at a specified price) from which she, in turn, will quote the best bid/ask rates to market makers. The latter are referred to as the broker’s ‘inside spread’. The broker earns a profit by charging a fee for her service of bringing buyers and sellers together. The foreign exchange market is therefore multiple dealer in nature.

More recently, automated brokerage trading systems have become popular in the foreign exchange market and perhaps the best known is the Reuters 2000–2 automated electronic trading system. This dealing system allows a bank dealer to enter buy and/or sell prices directly into the system thereby avoiding the need for a human, voice based, broker (and it is therefore seen as more cost effective). The D2000-2 records the touch, which is the highest bid and lowest ask price. This differs importantly from so-called indicative foreign exchange pages which show the latest update of the bid and ask entered by a single identified bank. The system also shows the quantity that the bank was willing to deal in, which is shown in integers of $1 million. The limit orders are also stored in these systems but are not revealed. A member of the trading system (i.e. another bank) can hit either the bid or ask price via his own computer terminal. The trading system then checks if the deal is prudential to both parties and if it is the deal goes ahead, with the transaction price being posted on the screen. Associated with the price is the change in quantity of the bid (ask) and also in the price offered if the size of the deal exhausts the quantity offered at the previous price. These concepts are discussed in more detail in Chapter 14.

1.3 A snapshot of the global foreign exchange market in 2001

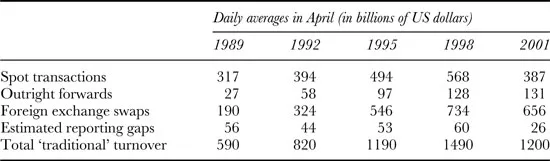

The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) produces a triennial global survey of turnover in the foreign exchange market gathered from data collected by its 48 participating central banks. These surveys have been conducted since 1989 and the latest available at the time of writing was the 2001 survey (see BIS 2001). This showed that average daily turnover in ‘traditional’ foreign exchange markets – spot transactions, outright forwards and foreign exchange swaps – in 2001 was $1.2 trillion, compared with $1.49 trillion in April 1998, a 19% fall in volume at current exchange rates (a 14% fall at constant exchange rates). The breakdown is shown in Table 1.1, which shows that the biggest hit occurred in terms of spot transactions and foreign exchange swaps, with outright forward contracts increasing slightly.

As the BIS notes, this decline in foreign exchange market turnover does not reflect a change in the pattern of exchange rate volatility (see Table 1.2), but rather the introduction of the euro, the growing share of electronic brokering in the spot interbank market, consolidation in the banking industry and international concentration in the corporate sector (see Galati 2001 for a further discussion).

The share of interbank trading in total turnover in 2001 was 58%, a decline of 5% over the previous survey, a decline attributed to the increased role of electronic brokering, which implied that foreign exchange dealers needed to trade less actively with each other. The share of bank to non-financial customer trading stood at 13% in 2001, a 4% fall from the 1998 figure and the share of activity between banks and non-bank financial customers rose from 20% to 28% in 2001 change and substantially between 1998 and 2001.

Table 1.1 Global foreign exchange market turnover1

Source: BIS (2001).

Note

1 Adjusted for local and cross border double-counting.

Table 1.2 Volumes and volatility of foreign exchange turnover1

Source: BIS (2001).

Notes

1 Volumes in billions of US dollars; volatilities in terms of standard deviations of annualised daily returns computed over calendar months.

2 Prior to 1989, Deutsche mark.

The introduction of the euro appears to have reduced turnover because of the elimination of intra-EMS trade: the euro entered on one side of 38% of all foreign exchange transactions, which is higher than the DMs share in 1998, and it is lower than the sum of the euro components in 1998. See Table 1.3 for further details.

The dollar remained the currenc...