1

Ingredients for effective learning: the Learning Combination Lock

Colin Beard and John P.Wilson

Introduction

Do all your first year students still arrive bright and keen at 9.00 a.m. on a Monday morning in the last week of the semester? How do we design their learning experience to sustain interest, motivation and enthusiasm? Do we go with our instincts and encourage learning through applying methods that have worked in the past, or do we base our teaching on theories of learning and, if so, which ones from the vast range that exists?

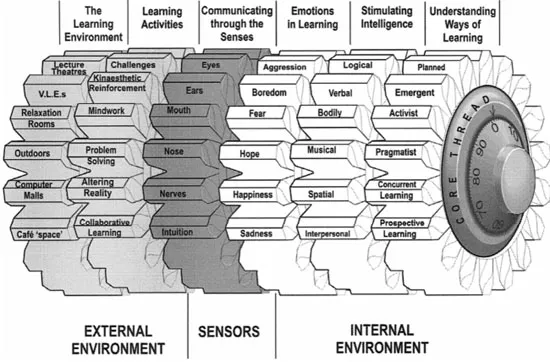

Our answer to this dilemma is a model that offers a systematic process for the educator to consider and select from a vast range of ingredients available in the development of learning processes: the Learning Combination Lock (LCL). The LCL can also be used as a diagnostic tool to examine existing programmes and determine whether they cover the main elements of the learning process.

The LCL is not intended to be used mechanistically but rather as a diagnostic aide-memoire that may also be added to and developed according to the considerations of the programme and the needs of the learner. This chapter describes the LCL and offers a range of clues and practical applications that may be used to enhance your students’ learning environment and link theory and practice.

Introducing the LCL

Theories of learning, education, training and development are frequently developed in isolation from one another. As a result, even educational specialists find it difficult to construct a coherent and integrated overview of their subject. And the vast majority of people involved with individual and work-based learning only appear to use a restricted number of theories (Brant, 1998). Many have neither the breadth of knowledge to select from a wider range of possibilities and options, nor do they possess a meta-model with which to contextualise and make sense of other theories with which they come into contact. The LCL provides such a meta-model. It is underpinned by models of experiential learning and theories of perception and information-processing (for a full explanation, see Beard and Wilson, 2002—this chapter concentrates on the applications and implications).

The LCL brings together (for the first time, to our knowledge) all the main ingredients of the learning equation (Figure 1.1). In the past these ingredients have often been discussed in isolation, thus giving only a partial picture of the learning environment. We need to identify all the core components to help practitioners in Higher Education diagnose and design activities that create high-quality learning experiences for students. For example, Light and Cox (2001:109) note that:

Figure 1.1 The Learning Combination Lock by Colin Beard

The design of this relationship between lecture structures and activities provides the key location for creativity and innovation in lecturing. Even given the usual academic constraints of what is ‘permissible’ as well as those of space, time, resources and so forth, the permutations and possibilities available to the lecturer are limited primarily by their imagination and confidence.

As lecturers we need to experiment and sometimes take risks in our own learning journeys. The LCL can support the creative exploration of activity design, although we cannot ignore the institutional difficulties of generating effective approaches:

The cultural environment of higher education does little to foster active learning to strengthen critical thinking and creativity skills in its students…. Faculty are given little time, budget, encouragement or support to develop ‘active learning’ tools that assist in developing these skills. Incorporating ‘active learning’ pedagogic techniques, for example, developing and running exercises, group projects, or simulations, is risky for a faculty and there is no guarantee that these techniques will work or that students see the benefits of this form of pedagogic method. Fortunately, but slowly, the cultural environment that places barriers to moving toward more innovative pedagogical tools is eroding away.

(Snyder, 2003:159)

We are not presenting fixed choices in the LCL but offering many more possibilities to experiment with and reflect upon. Starting on the left, the learning environment tumbler identifies various components found in the physical external environment that may be used as part of the learning process. Adjacent is the tumbler that examines the core components of learning activities. The third tumbler represents the senses as the mediator that connects the external environment with the internal cognitive environment. Our senses alert us to the presence of the stimuli that begin the process of perceiving and interpreting.

The emotions tumbler presents some of the vast range of emotional responses we can make and is a very powerful aspect of the learning equation. In designing a learning programme we may wish to instil certain emotions to enhance the learning situation as well as manage and recognise the emotional agenda of the broader student experience.

The fifth tumbler explores various forms of intelligence whose development may be the objective of the learning process.

The final tumbler represents various theories of learning. There is still so much that we do not know about learning, so it is important to be aware of the various learning theories and also our own underlying theories of how learning may best be facilitated. By making these explicit we may better understand our own thinking and the behaviour and motives of learners.

The tumblers explained

Tumbler 1: the learning environment

The external learning environment provides opportunities to encourage learning. For example, outdoor environments increasingly provide very real opportunities for the individual to learn in a deep way about themselves and their interactions with others. And, it isn’t only the external environment that can provide valuable opportunities to learn. The design and use of the indoor student learning environment is beginning to metamorphose. Whereas in the past it was strongly associated with the lecture theatre and textbooks, nowadays it includes: distance education sites; common areas such as halls; social group work space with sofas; outdoor green spaces; amphitheatres; video clips; and virtual discussion groups. An illustration of the transition in thinking is the definition of the learning environment by Indiana University, and their support for active learning:

A physical, intellectual, psychological environment which facilitates learning through connectivity and community.

(www-lib.iupui.edu/itt/planlearn/part1.html,

accessed 27 November, 2004)

Well-established research shows that students learn best when they are actively engaged rather than being passive observers…there are three avenues an institution can promote to foster active student learning. First, certain teaching methodologies, such as problem-based learning, promote active student involvement. Second, the classroom furnishings can either enhance or hinder active student learning. Thus, tables and moveable chairs enhance while fixed-row seating hinders active learning. Finally technologies which require student initiative, such as interactive video-discs, promote active learning.

(www-lib.iupui.edu/itt/planlearn/execsumm.html,

accessed 27 November, 2004)

Of course, ‘furnishings’ represent a small fraction of the many physical elements that can be managed in the learners’ environment. Informal learning environments are increasingly being recognised and used for more formal learning. While students traditionally spent many hundreds of hours learning in lecture theatres and seminar rooms, learning space is increasingly spilling over into, and being used alongside: informal learning spaces; drama studios; stage; laboratory; virtual learning environments; lecture theatres; seminar rooms; café learning spaces; group spaces; stand-up corridor computer malls; and even innovation rooms and relaxation lecture theatres, including the use of hammocks in lecture theatres in Finland, specifically designed to enhance the creation of certain mental states, such as relaxed alertness (see also Beard and Wilson, 2002). There is growing evidence elsewhere too that new learning spaces are evolving:

[Arizona State University has a] special Kaleidoscope room [which] holds 120 students; however, the faculty is never more than five rows away from any student. The instructor relates to a few groups of students rather than a mass of 120 students…the atmosphere is one of work, action, involvement…. Stanford University has designed highly flexible technology-rich class-lab learning environments using bean bags for much the same purpose as tables…. We recommend that the entire planning process for design and renovation of classrooms includes faculty and staff with expertise in learning methodologies.

(www-lib.iupui.edu/itt/planlearn/part1.html,

accessed 27 November, 2004)

Unfortunately, the lack of knowledge about the relationship between buildings and learning, and the lack of dialogue between academics and facilities managers is still constraining developments (Beard and Matzdorf, 2004) and so academics are often left to merely adapt to given space. Furthermore, the replacement of old learning spaces with new facilities is expensive and is a long-term investment.

Smith (1998) argues that: ‘We are not designed to sit slumped behind a piece of wood for an hour and ten minutes at a time, nor are we designed to sit for three hours in front of a television screen or a computer terminal’ Similarly, Jensen (1995) refers to the work of Dunn and Dunn (1978) who found that ‘at least 20% of learners are significantly affected, positively or negatively, by seating options or lack of them’. So perhaps we do need to explore more innovative use of existing space until such time that the design of learning space sits more at ease alongside pedagogical requirements. Floor space and wall space can be used for creative, more active engagement of learners (see case study 3 below).

Technological tools are also influencing learning space, with items such as interactive whiteboards, which can enable the instant capturing of fresh, ‘live’ and indigenous intellectual property. As pedagogy interacts with the operational facilities and media technology, the learning environment will undergo rapid change. This will change the future layout of walls and learning space and enable active movement of people and information. This is important, for we believe that good learning environments will increasingly provide areas that maximise the flexibility and mobility of information, people and space, enabling the physical viewing of information and concepts from different perspectives.

Tumbler 2: the learning activities

This second tumbler explores principles of designing learning activities. Creating a real sense of engagement in an active learning journey, to bridge the gap between where a student starts and the desired learning outcomes, over periods of time such as a semester or a year or the duration of a degree, can be a transformative experience for students. Journeying, with its sense of setting off, building, constructing, changing and arriving, includes all the important conceptual ingredients to generate powerful experiential learning.

The American Association for Higher Education (AAHE) states that an important principle for good practice in undergraduate education should be the development of an environment in which ‘active learning’ is encouraged (Snyder, 2003:159). Snyder also refers to a number of studies comparing active learning with those using passive learning, showing that active learning methods generally result in greater retention of material at the end of a class, superior problem solving skills, more positive attitudes and higher motivation for future learning.

By ‘active’ learning methods we mean intellectually, physically and emotionally more active as well as more active in the design and selection of learning activities. Active learning can offer a greater depth of information-processing, greater comprehension and better retention, in contrast with the passive learning techniques that characterise the typical classroom, in which lecturer wisdom is offered for students to dutifully record notes. Active learning involves students doing something and taking a participatory role in thinking and learning. The milieu of activities can include elements such as: kinaesthetic activity; mental challenges; experiencing a learning journey; overcoming obstacles; following or changing rules; and altering reality (see Beard and Wilson (2002) for a full explanation of altering reality). Although much more research is needed into learning activities used in Higher Education, a basic typology of activity might for example include:

- Creating a sense of a learning journey for students, with a clear vision of the bigger picture, with a clear destination, and route maps to guide the way.

- Creating and sequencing an array of intellectually, physically and emotionally stimulating ‘waves’ of activities.

- Adjusting or suspending elements of simulation and reality to create learning steps.

- Creating activities to stimulate and regularly alter moods…acknowledge the student experience, create relaxed alertness, understand peak or flow learning.

- Using the notion of constructing or deconstructing activities, such as physical objects, or nonphysical items, e.g. the gradual construction of a model, a concept, historical maps, key ingredients, typologies, a phrase or poem.

- Creating and managing the learning community through a mixture of collaborative, competitive or co-operative strategies.

- Creating and acknowledging feelings, values, targets, ground-rules, restrictions, obstacles and allowing students to address identity, change, success and failure.

- Considering multi-sensory teaching—see the next cog—experiment with building in a holistic ‘sense’ of the material covered…onsider the sensory enhancement of material, e.g. touch, smell, colour…

- Providing elements of real or perceived challenge or risk…and allow students to address risk and the stretching of personal boundaries.

- Introducing complex design, sorting and/or organisational skills.

- Developing generic functional student skills alongside specific course content work—such as literature searching, writing introductions, conclusions, researching skills, etc.

- Designi...