![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

This chapter will help to set your experience as an ECR in a global context, as we explore the policies and practices of different institutions to find an all-encompassing definition of what it means to be an early career researcher. We then discuss what your role might involve and the status you might have in your institution and within the academic community more widely. As the last few years have seen changes in the development of the ECR role and its support mechanisms, this is a timely moment to consider the drivers for these changes, and to think about what they might mean for your future career.

Starting out as an Early Career Researcher (ECR), you might be thinking about how your role fits within the academic community, not just of your department and institution, but of your discipline, and not just in your own country, but on a global scale. The term itself is relatively new but the concept of postdoctoral workers in the USA can be traced back to 1876 when the first president of Johns Hopkins University came up with the idea of offering $500 fellowships to a select group of 20 graduates interested in further studies of literature or science. Among this group were four men with doctoral degrees who therefore became the first postdocs.

It is estimated that there are approximately 90,000 ECRs in the USA and more than 30,000 in the UK, which must translate to a few hundred thousand worldwide (National Science Board 2008; Second Annual Report on Research Staff, Funders Forum 2009). However, despite these numbers, these researchers have largely been ignored in academic studies and there is little guidance published for them, hence the need for this book, which is aimed directly at you as an ECR, and at the mentors and other colleagues who will help to shape your experience and career.

What is an ECR?

Not that long ago there were fairly clear divisions between researchers at different stages throughout their career, starting with doctoral students then progressing to postdoctoral workers and finishing with academic staff. However, more recently throughout Europe and to an extent worldwide, the term Early Career Researcher (ECR) has been introduced, which overlaps all three stages although it primarily replaces those who were called postdoctoral workers. This has partly been a response to the increasing importance of researchers, which has been reflected by their increased respect and status shown by national, international and funding bodies.

As will be clear from this description, and perhaps from your own experience, an ECR does not automatically equate to a postdoctoral worker. Also, the term ECR is not universally accepted and there are alternative names which are used (Johnson 2009: 5). It has been pointed out that the lack of a consistent definition of postdoctoral workers or agreement on the precise nature of the population concerned has hampered research into the character of postdoctoral positions (Akerlind 2005:25).

To set the scene, in the context of the Bologna process in Europe, doctoral education is the third cycle of higher education and the first stage of a new researcher’s career. In Europe but outside of the UK, the term Early Stage Researcher (ESR) is Salzburg Principle no. 4 (a set of ten basic principles concerning doctoral programmes and research training); it is used to describe a PhD student and ‘covers the first 4 years of experience in research or the period until a doctoral degree is obtained, whichever is shorter’. However, in the European Charter (European Commission 2005: 29) the situation becomes confused as Experienced Researchers

are defined as researchers having at least four years of research experience (full-time equivalent) since gaining a university diploma giving them access to doctoral studies, in the country in which the degree/diploma was obtained, or researchers already in possession of a doctoral degree, regardless of the time taken to acquire it.

Therefore, by European terminology it is difficult to differentiate between ECRs and experienced researchers! Care must also be taken about using the terms Early Career Investigator (ECI) and Early Stage Investigator (ESI) as used in the USA. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) defines these as a person within 10 years of completing their terminal research degree or medical residency, which is likely to be very different to a doctoral student in the European context.

In the UK, the Arts and Humanities Research Council defines an ECR as someone ‘within eight years of the award of your PhD or equivalent professional training or within six years of your first academic appointment’. In Australia, the Australian Research Council defines early career status as:

An early career researcher is one who is currently within their first five years of academic or other research related employment allowing uninterrupted, stable research development following completion of their postgraduate research training.

Similarly, in the USA for the Wickham Skinner Awards, the term ECR is used and is defined ‘as someone who has received a doctoral degree within the previous six years’.

For the purpose of this book and to respect definitions worldwide, we will categorise ECRs as those researchers who range from senior doctoral students to postdoctoral workers who may have up to 10 years postdoctoral education; the latter group may therefore include early career or junior academics. The topics that we cover in the book should be relevant to you, whichever of these groups you fall in to – and they will also have implications for your mentor, supervisor or other colleagues as they work alongside you during this stage of your career.

Given the range of experience that many people bring to the role of ECR, you might feel most comfortable with the in-depth definition provided on its website by the National Postdoctoral Association of the USA, which states that

a postdoctoral scholar (‘postdoc’) is an individual holding a doctoral degree who is engaged in a temporary period of mentored research and/or scholarly training for the purpose of acquiring the professional skills needed to pursue a career path of his or her choosing.

(http://www.nationalpostdoc.org/policy/what-is-a-postdoc)

Role of an ECR

So why do academic institutions need ECRs? You might be asking yourself that question – or wanting to provide answers for those around you! There is no doubt that increasing the number of highly skilled researchers makes a significant contribution to the production of national and international knowledge and innovation. Moreover, in a global economy, society needs highly trained employees who are adaptable and mobile, and are able to work effectively in a variety of different contexts within and outside of academia, during their professional careers.

An example of the importance of postdoctoral experience is particularly highlighted in a cohort of biochemists from the USA during the 1980s in which

a postdoc appointment is regarded as a necessary step after doctoral completion, whether the individual plans a career in academia or in the business, government or non profit sectors. Consequently, the postdoc, not the PhD, has become the general proving ground for academic excellence, scientific entrepreneurship, and ultimate intellectual independence.

(Science 1999: 1533)

However, more recent research (Brown, Lauder, and Ashton 2008) has challenged the direct link between economic success and education. Emerging economies such as India and China are rapidly building up their education system so that high-skill people in low-cost countries become an attractive option for multinational companies. This could result in a situation where young people in developed countries who are investing heavily in their education, may struggle to find employment in the careers to which they aspire. It would appear that it is timely to debate the future of education and skills and their relationship to careers, prosperity and social justice in a global economy. The days of assuming that higher levels of education will automatically lead to success in the global job market are coming to an end.

Not so long ago when there were fewer ECRs around, a large proportion would have gained future employment in universities. However, this situation has changed considerably and in contrast, the majority of ECRs will not take up academic positions. As we discuss in later chapters, your own perspective on this might affect your decisions about how to prioritise your efforts during your ECR years – your decisions about whether (and where) to publish, for example, will assume different significance according to your future prospects.

Historically most universities have not maintained very accurate records of the numbers of ECRs on campus, and although that situation is changing, it is still difficult to obtain data on how ECRs progress in their career, and instead we have to rely on data on career destination and progression of doctoral graduates.

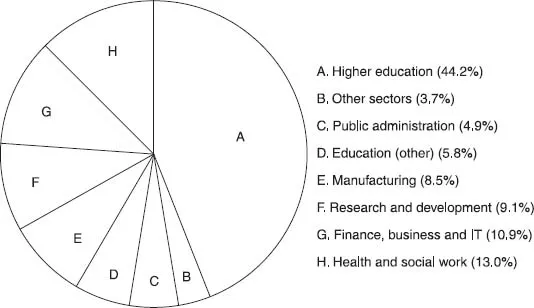

In a recent UK study of the first employment destinations of doctoral graduates from 2003–2007, 35% went into research roles across all sectors, with higher education being the main destination where 23% of all respondents were employed as research staff and 14% as lecturers (Vitae 2009a). Similarly, in related publications looking at career profiles of doctoral graduates (where almost 70% were from science or engineering backgrounds), less than half of graduates across all subject areas were employed in the education sector (Vitae 2009b; Vitae 2010a). Obviously, this means that a large number of ECRs will not be employed in academia – some through the choice of a different career path and others after a disappointing period of applying for a limited number of academic jobs. In a time of uncertain academic employment, it might be encouraging to remember that as an ECR you will gain many generic and transferable skills, which you can benefit from in a more varied job market (Figure 1.1).

Status of an ECR

Concerns with postdoctoral research training and employment outcomes have been growing at an international level and have included increasing dissatisfaction among postdoctoral workers with the nature of their position (Akerlind 2005: 1). Similarly, in a review of the postdoctoral system in the USA, postdoctoral researchers were described as ‘in a kind of limbo between student and independent researcher, without the status that their peers in other professions enjoy’ (Mervis 1999: 1513). However, in 2009, the NIH announced a new policy (NOT-OD-09-021) designed to encourage early transition to research independence. In a study of postdoctoral fellows in Canada, a key area of concern was the low value placed on postdoctoral researchers by institutions (Helbing, Verhoef, and Wellington 1998). It is clear therefore, that many postdoctoral researchers have status concerns and this has been highlighted in a recent European report (European University Association 2007: 30) where more countries did not recognise the status officially than those that did.

Figure 1.1 Employment sectors for all doctoral graduate respondents in UK employment (November 2008). From Vitae (2010a) What do researchers do? Doctoral graduate destinations and impact three years on (p. 15).

In an Australian example, gaining and maintaining research council large-grant funding for one’s own research is the most significant hurdle to overcome in becoming established and accepted as a career researcher in academia (Bazeley 2003: 269). Knowing what information is used to assess ECR status can be helpful in planning your own strategy for success, and Bazeley (2003: 275) outlines these as follows:

• research qualification;

• year in which research qualification was obtained;

• current position, including year and level of appointment;

• year of first non-casual appointment to an academic institution;

• year of first non-casual appointment in the current place of employment;

• significant periods of absence from a research environment after qualifying with PhD;

• number, duration and type of research fellowships which have been held;

• position with respect to grants held during past 5 years;

• research output during the last 5 years.

The implication here is that excellent performance in the above will more likely lead to independent researcher status and academic positions.

The European Charter for Researchers (European Commission 2005: 27) makes the following statement:

Clear rules and explicit guidelines for the recruitment and appointment of postdoctoral researchers, including the maximum duration and the objectives of such appointments, should be established by the institutions appointing postdoctoral researchers. Such guidelines should take into account time spent in prior postdoctoral appointments at other institutions and take into consideration that the postdoctoral status should be transitional, with the primary purpose of providing additional professional development opportunities for a research career in the context of long-term career prospects.

In the UK a significant development in employment law is discussed in detail in the University and College Union’s (UCU) The Researchers’ Survival Guide, which refers to The Fixed-Term Employees (Prevention of Less Favourable Treatment) Regulations 2002 (University and College Union 2008). Essentially this means that staff such as ECRs on fixed-term contracts (sometimes also known as contract research staff) must be treated no less f...