- 204 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Tropical Rainforests

About this book

Tropical Rainforests presents the most up-to-date and wide-ranging review of the problems and prospects of the world's most complex and abundant ecosystem. Chris Park examines where and how fast rainforests are being cleared, drawing on examples from all major forest areas. The consequences of clearance are examined at local, regional and global scales. The author achieves a balanced overview of the current state of the world's rainforests, discussing both the consequences of clearance (for ecology, environments and peoples) and the possible solutions (such as conservation and protection, reforestation, sustainable management, changing tropical timber trade and international investment programmes). Well illustrated with maps, figures and photographs and with a comprehensive bibliography, Tropical Rainforests provides an essential introduction for students of Geography, Ecology and the environment, teachers, environmentalists, development practitioners and the general public.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

THE TROPICAL RAINFOREST: HISTORY AND ENVIRONMENT

This is the forest primeval

Henry Longfellow, Evangeline (1847)

1.1 INTRODUCTION

Tropical rainforests are the most complex ecosystems on earth. Rainforests (better known to many people as jungles) have been the dominant form of vegetation in the tropics for literally millions of years, and beneath their high canopy lives a diversity of species which is unrivalled anywhere else on earth.

1.1a Images and impressions

For more than a century travellers have recorded vivid descriptions of the rainforests, which emphasise abundance and grandeur. Charles Darwin kept a detailed log of his impressions of the forests around Rio de Janeiro, which he visited in April 1832 during the voyage of the Beagle. He wrote:

After passing through some cultivated country, we entered a forest, which in the grandeur of all its parts could not be exceeded. …The trees were very lofty, and remarkable, compared with those of Europe, from the whiteness of their trunks…. The forest abounded with beautiful objects…. The greater number of trees, although so lofty, are not more than three or four feet in circumference…. It is easy to specify the individual objects of admiration in these grand scenes; but it is not possible to give an adequate idea of the higher feelings of wonder, astonishment, and devotion, which fill and elevate the mind.1

Since about 1980 interest in the rainforest has shifted full circle. From being seen as a threat or nuisance, it is now widely seen as under threat, with mounting concern for its future survival. The place to be tamed and conquered is how viewed as a place to preserve and protect.

This about-turn in attitude has been triggered by the real threat of destruction and clearance of the rainforest habitat world-wide. Although clearance per se is not new, the pace of deforestation is faster than ever before, and there are real fears that within one generation there will be hardly any natural rainforest left anywhere in the world.

There is already a fairly sizeable literature on the character and dynamics of tropical rainforests.2 In this book we will examine why the rainforest is so important, why it is being cleared, what the consequences of this clearance are and what solutions are available. But first we need to define exactly what we mean by the term ‘rainforest’, examine where it is found and reflect on why it is regarded as the most important ecosystem on earth.

1.1b Classification

The rainforest is one of several types of forest found throughout the tropics, and each type has different characteristics.3

The closed forests account for about half of the total area of tropical forest (around 62 per cent of the natural tropical forest) and comprise two types of continuous tree cover (Table 1.1). Eleven-twelfths of the closed forests, by area, are tropical moist forests and the rest are deciduous and semi-deciduous forests of various types. About two-thirds of the moist forests are tropical rainforests, composed of evergreen broadleaved trees which flourish in the high temperature and humidity of the low latitudes. The tropical moist deciduous forests (or monsoon forests) grow on the fringes of the tropical rainforests, and lose their leaves in the dry season.

Table 1.1 Distribution of tropical forest types

Most of the remaining tropical forests are open woodland, including shrublands and types of savanna, pasture and grassland which are partly wooded.

Almost all (97 per cent) of the tropical forests which have been modified by human activity are fallow forests, areas which have recently been farmed and then abandoned or left to regenerate naturally. Only a very small area is covered by tropical forest plantations. The industrial plantations produce commercial timber, pulpwood or charcoal; the non-industrial plantations are mainly for fuelwood production or environmental protection.

1.1c Distribution

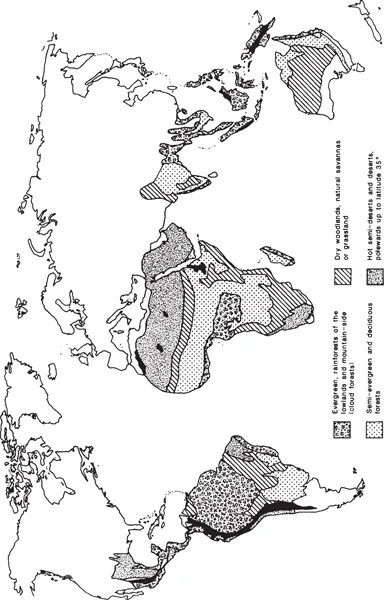

The tropical rainforests provide a discontinuous belt of green around the globe, between the tropic of Cancer (23.5° north) and the tropic of Capricorn (23.5° south). Dense rainforest is the natural climax vegetation of the hot, humid tropical zone and it flourishes particularly in the lower latitudes (between 10° north and south of the equator). Just under half of the tropical zone (49 per cent according to the World Resources Institute)4 is covered by forests (Figure 1.1).

Most of the tropical countries with surviving rainforests are developing countries, for whom the forests provide a valuable capital asset.

The total area presently covered by tropical rainforests is estimated at 12 million km2, which accounts for nearly a third of the world’s forests (covering roughly 30 million km2).5 The distribution of forests within the tropics is uneven, reflecting the distribution of land and sea and the impacts of this on climatic boundaries. The latitudinal boundaries of the rainforest are determined mainly by precipitation, while altitudinal limits are determined more by temperature. Some rainforests thrive beyond the 10° north and south latitudes, where high rainfall encourages forest growth. Such patches occur in Central America, the north-east coast of Australia and the great valleys of southern China.

The main rainforests today are found in three areas (Figure 1.1 and Table 1.2)—Latin America, Western Equatorial Africa and South-East Asia. Latin America houses the American Formation which is dominated by the Amazon and Orinoco Basins. It has over half (56 per cent) of the world total, much of it (3.31 million km2, 48 per cent of the area’s total) in Brazil and the rest in Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Venezuela and French Guiana. Amazonia is the world’s largest and most important surviving rainforest.6

The remaining rainforests are scattered in sixteen countries in West and Central Africa (18 per cent of the world total) and South-East Asia (25 per cent of the world total). The African Formation includes the Cameroons and the Congo Basin in countries such as Gabon, Zaïre and Madagascar. The Indo-Malaysian Formation in South-East Asia includes parts of western and southern India, the Far East (especially in Indonesia—particularly Borneo and Papua New Guinea—which now has about 10 per cent of the world’s remaining tropical rainforest) and north Australia.

Figure 1.1Global distribution of tropical forests.

Source: after Gross (1990)

Table 1.2 Distribution of tropical forests

1.1d Lack of reliable information

It is surprisingly difficult to define exactly what the total area of rainforest is today, for various reasons.7 Some countries have better (and more complete) survey coverage than others, and not all of the figures available refer to the same year. Recent developments in remote sensing technologies promise much better survey coverage in the future,8 although between 1970 and 1988 less than 60 per cent of tropical forests had been surveyed using any form of remote sensing, particularly available satellite technologies which are costly.9

Figures reported by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation and by individual countries are often underestimates. Figures quoted by campaigning groups must also be treated with some caution, because such groups may well overestimate rates of forest clearance and underestimate the size of remaining areas. Estimates also vary because they include different types of forest cover. Some, for example, include coniferous and bamboo forests as well as broadleaved forests, whereas others do not. It is also difficult to distinguish between primary (original) and secondary (regrowth) forest cover, even in satellite images, so that quoted figures might not always be comparing like with like.

The most recent reliable information on areas of tropical forests comes from the World Resources Institute.10 These figures (Table 1.2) provide a valuable framework for examining the distribution of tropical forests today and a useful baseline for assessing rates and patterns of deforestation (in Chapter 2).

The proportion of the earth’s land surface covered by rainforest is small (around 8 per cent),11 but its significance is considerable. Possibly half (up to 90 per cent according to some experts) of the total number of species of plants and animals found anywhere on earth are found either exclusively or mainly within tropical forests.12 We will evaluate the wider significance of the rainforests in Chapter 4, particularly in terms of what would be lost if all remaining forests were to be cleared.

1.2 CLIMATE AND RAINFORESTS

Climate exerts a strong influence over the broad distribution of rainforests within the tropics. It also has a marked effect on regional patterns and structures of rainforest vegetation and habitat.

Rainforests occur in hot moist climates. They receive more solar radiation throughout the year than any other vegetation zone on earth, which promotes the rich variety and luxurious character of vegetation.

1.2a Characteristic climate

The typical rainforest climate has two main distinguishing features—relatively constant temperatures, and heavy rainfall. Tropical forests grow under a narrow range of temperatures but a fairly wide range of precipitation (Figure 1.2). The combination of these two climatic controls creates the very special environment for rainforest growth.

Temperatures in rainforest areas are high, and they vary relatively little throughout the year. Temperatures remain fairly constant at between 20°C and 28°C through the year,13 the warmest months perhaps a degree or so higher than the coldest months in a given place. This uniformity occurs because the sun is mostly overhead, so variations in the length of daylight throughout the year are limited.

Temperature variations are often greater from day to night than from month to month, so that rainforest dynamics are more variable over short-term diurnal cycles than over longer seasonal or annual timescales. Diurnal temperature variations might be as high as 17°C. Intense heat during the afternoon (when temperatures may reach 35°C) gives way to cold at night (temperatures may fall as low as 18°C), then fresh conditions in the morning, in a never-ending rhythm of daily change. Many tropical areas have a fairly predictable daily cycle of weather dictated by temperature and ...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- PLATES

- FIGURES AND TABLES

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- 1: THE TROPICAL RAINFOREST: HISTORY AND ENVIRONMENT

- 2: DESTRUCTION OF THE RAINFOREST: RATES OF LOSS

- 3: CAUSES AND PROCESSES OF CLEARANCE

- 4: IMPACTS AND COSTS OF DESTRUCTION

- 5: FOREST PEOPLES

- 6: POSSIBLE SOLUTIONS

- NOTES

- REFERENCES

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Tropical Rainforests by Chris C. Park in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Environmental Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.