This is a test

- 672 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Making of Modern Europe, 1648-1780

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This reissue of a classic textbook has been revised and updated with a new introduction by the author. Geoffrey Treasure provides a thoroughly comprehensive account of the European experience at a time when so much of what is today identified as 'modern' began to take shape.Discussing key issues of the period, The Making of Modern Europe, 1647–1980 examines:

- the evolution of the developing society

- detailed studies of the people, their environment, attitudes and beliefs

- economic aspects

- the growth of the states

- politics, war and diplomacy

- religion, intellectualism and science.

This work provides an excellent grounding for the study of seventeenth and eighteenth-century European history.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Making of Modern Europe, 1648-1780 by Geoffrey Treasure in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

1

THE EUROPEAN WORLD

The Bounds

In 1600, ‘Europe’ was still a term without precise political significance, an area without recognized external frontiers, except where seas provided them. During the century, as frontiers were delineated in diplomatic encounters of an increasingly sophisticated kind, the idea of Europe came to mean more. A cosmopolitan civilization was evolving. Though they may distinguish between eastern and western Europe, historians who write about this or that ‘revolution’, military, scientific or commercial, envisage the continent as a whole rather than a single state. By 1700 statesmen like the Anglo-Dutch William III had begun to talk about Europe as an interest to be defended against the ambition of a particular state. Louis XIV, with 20 million subjects, sovereign of about a fifth of the people of Europe, spoke confidently of ‘giving peace to Europe’. Congresses assembled periodically after the peace of Westphalia (1648), itself the product of the first of such diplomatic gatherings, to settle European questions of peace and war, boundaries, commercial and political rights.

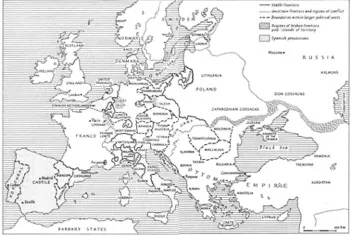

Map 1.1 European frontiers in 1640

The western state system had broadened by 1600 to include all the continent from the Hebrides to the Dardanelles, but there remained a fringe area, from Norway to the Caspian sea, of states moving in their own orbits, absorbed in questions which mattered little to the Atlantic and Mediterranean powers. Commercial interests drew England, France and Holland to the Baltic and diplomacy had created certain links: Henry Valois became king of Poland, James I of England married Anne of Denmark. But it was still usual for western statesmen to treat the Baltic states as belonging to a separate northern system, governed by its own interests and its own power balance. While the states appeared to be spending much of their energy upon fighting each other, political experience, economic progress and certain common cultural trends were binding them more closely together. Warfare, after 1648, was conducted on a grand scale but was limited both in objectives and, except indirectly, in its effect upon civilians: a deadly sport for professionals, the soldiers and their political masters.

Awareness of allegiance to a country, even where, as in France or Spain, there was an honoured tradition and a political reality behind the idea, seems to have been confined to quite small groups who had rights, responsibilities and an educated vision of this transcendent idea. It was beyond the ken of the ordinary villager or townsman for whom ‘the political nation’ only existed in the shape of the tax collector. The last century and a half of Europe’s ancien régime was to see a general growth in the powers of the states; only Poland failed entirely in this respect and eventually paid the price. Yet the common features of government and societies remained more important than their differences. This book traces the separate course of particular states, but first examines the characteristics of the whole society. What lies before us is a whole culture and a continent still in equipoise, before the disruption and fragmentation that were to come with the rise of nationalism and the industrial democracies of modern times.

Turkey was in Europe but scarcely of it. The outposts of Ottoman power, and its satellites, defined the long eastern boundary from Moldavia to Dalmatia and across the Mediterranean. The line between Orthodox Russia and the rest of Christian Europe was never so sharp as that which divided Christendom and Islam. Northwards, Europe simply petered out, as it were, in the immensity of the steppes, the Pripet marshes, and forests of birch and alder. Except among those immediately affected, such as Swedes, Lithuanians and Poles, there was vagueness and lack of interest more than hostility. During the seventeenth century, however, Russia was drawn into the European orbit. The peace of Andrussovo (1667), giving Tsar Alexis the formerly Polish lands east of the Dnieper, with the city of Kiev, was a milestone as notable as the peace of Carlowitz (1699) which secured Hungary for the Habsburgs. The stormy reign of Tsar Peter I saw a deliberate effort to force the western powers to take Russia seriously. By his death, in 1725, Russia was a European state: still colonizing rather than assimilating her eastern lands and relatively little affected by the process; interlocked, however, with the diplomatic system of the west; western in forms, if not spirit, of government. Renaissance men had drawn the north-eastern boundary of Europe not at the Urals, but at the Don. Now a larger Europe began to take shape as the Christian Balkan peoples, who had preserved their identities and traditions under a tolerant Turkish rule —Magyars, Croats, Serbs and Bulgars—began to lift their heads again. By 1700 the Dardanelles and the Bosphorus, the Black Sea, Caucasus and Urals marked the eastern limits. Still, however, the fringe lands remained indeterminate. Men were only starting to think, even in the west, of linear frontiers which defined the whole state rather than particular estates.

Racial differences were not yet being exploited for political ends, but they were important since they corresponded to characteristic cultures. Tall Teutons north of the Rhineland, round-headed Celts of the west, dark long-headed Mediterranean men and women provide some obvious contrasts. The high-cheekboned Slavs, originally the westward-migrating tribes checked by Charlemagne along the boundary which has ever since been one of the continent’s crucial lines of demarcation, were becoming less distinctive as German colonists and speech spread into Slav areas, but Slavonic dialects persisted. In Russia the eastern Slavs absorbed their Tartar neighbours; the southern Slavs of the Balkans lost their identity neither to Ottoman conquerors nor to Habsburg liberators. The development of national languages was pointing meanwhile towards one of the potent forces of the future; it was part of the process by which states extended their control over their subjects. In France, under the scrutiny of the Academy, founded in 1635, the refinement of the language prepared the way for its civilizing role; French was soon to displace Latin as the common language of Europe’s diplomats and savants. The Austrian bureaucracy, which had most to fear from racial and linguistic differences, used German wherever possible, so emphasizing its supremacy over Czech and Magyar. Everywhere the accepted usage of government and court was driving out the languages of minorities; everywhere provincial dialects were being abandoned by the educated: Provençal or Breton French would raise a smile at Versailles. The survival in Poland of the languages of several minorities, notably Ukrainian and German and the use of Latin for government business, was a mark of that country’s weakness.

A vital element in Europe yet not part of Christendom were the Jews, an alien people of great value to the parent society. Within Jewry were two strains: the Sephardim, who had fled from Spain to other parts of Europe, and the Ashkenazim, the poorer Jews of the north and east. Whether rich merchants and money lenders, or poor artisans, the Jews did more than survive. They were strengthened by the isolated conditions in which they were forced to live, and united in respect for their rabbis, ordained guardians of cherished laws and history. In 1655 Cromwell re-admitted them to England. From France and Spain they were still officially excluded, to the detriment of those countries, as the experience of Holland suggests. There Jews were able to live and work in peace. The career of Spinoza, for example, would have been unthinkable in any other land; indeed it was his own congregation of Jews that condemned him for his radical views. More tolerant attitudes gained ground elsewhere in the eighteenth century: ‘enlightened’ statesmen, like Pombal of Portugal, preferred Jews to Jesuits, but popular prejudice remained strong.

The Jews had ever to bear the guilt of the crucifixion—as Christians were often reminded by their priests. At a time when it was generally accepted that morality depended upon religion, the Jews were presumed to be immoral. They were usually despised even where, as in parts of Germany and in Poland, they were relatively numerous. Some four-fifths of all European Jews were living in Poland by 1772. Of these Jews at the time of the Cossack raids, drawing upon a communal tradition which exile had little devalued, the Yiddish writer Isaac Bashevis Singer has written powerfully in his novel The Slave (1962), describing the antagonisms roused by a vulnerable, alien culture. In Poland are encountered the extremes in Jewry: the immensely rich capitalists, often corrupt in the pursuit of money and office; the numerous poor, tenacious of life and faith amid urban squalor; the ultra-conservatives; the mystical devotees of the cult of Hasidinism. Elsewhere greater social disabilities rarely weakened their economic position. They were persistently successful in adapting their methods to the changing rhythms and patterns of international trade, resourceful in finance, especially in the enlarging fields of banking and maritime brokerage, and they benefited from the exchange of information and capital with trusted co-religionists in other centres. At the same time they managed to remain, though scattered, and often living in ghetto conditions, a distinct civilization: in Braudel’s words, ‘a kind of confessional nation’.

A Human Scale

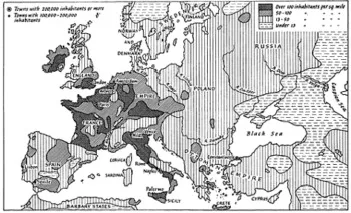

Map 1.2 Europe in the early seventeeth century: population

The exceptional situation of the Jews serves to emphasize the prime fact: Europe was Christendom. That was a significant term at a time when men almost universally accepted, in and over the animist world where magic still held many of them in thrall, the sovereignty of God and his laws, and when, at the start of the period, princes still believed that it might be their duty to defend Christianity against the infidel—and their own version of the faith against their fellow Christians. The churches which embodied the various interpretations of Christian truth were, as institutions, the grandest expression of the corporate ideal that shaped life at all levels. It can also be seen in institutions as distinctive in style and purpose as the cofradías of Spain or the scuole of Venice; or as universal as the guilds that everywhere controlled both conditions of employment and the production and marketing of goods. The order, college, guild or fraternity provided for nobles, churchmen, professional men, merchants and craftsmen alike the framework of social discipline; with it went that civilizing sense of belonging to a family of common interests which had been the positive aspect of ‘feudalism’ and which still characterized attitudes and institutions.

Certain ‘feudal’ characteristics persisted: notably in the countryside, in the shape of varying forms of personal service and dues owed by peasant to landowner; also in armies and courts where conditions of service still reflected the arrangements of earlier times when all power stemmed from the ownership of land. Europeans today are not only inheritors of the individualist ethic based upon ‘natural’ rights, but are also members of the systems, in some degree socialist or collectivism which have arisen in response to the need to protect the individual from the abuse of those rights in a capitalist economy. It is hard therefore for them to grasp the character of an earlier society in which a man belonged to a mystical body, his church (the Reformation only increased for Protestants the sense of belonging); to a political authority, his prince; and to his local community, town or village, in which all were known and placed in accepted hierarchy: there his rights depended on the rank to which he was born, or the body to which he belonged by reason of his craft or profession. Citizens today, in a world which has experienced so much uprooting, such rupture or, at best, progressive departure from old ways, may find strange the values and insights of men who lived according to immemorial rhythms and at a pace which had hardly quickened in fifteen hundred years. Marlborough’s men moved at the pace of the Roman legionaries.

Those who can cross the Atlantic in four hours have to adjust to the mentality of men for whom 40 kilometres a day was a good average journey on horseback, who would not expect to reach Antwerp, travelling from Venice by land or sea, in under fourteen days. Used to the rule of accurate clocks and watches they have to imagine daily living within a framework of light and darkness, not precise time. Accustomed to nearly universal literacy they have to make an imaginative effort to recall the people of an oral culture, who were attuned to ancestral voices and presences and who taught and learned more by precept than by reason’s law. In the seventeenth century only about one in five of the adult population was able to read and write. The proportion, which rose significantly only in the second half of the eighteenth century, was lower among women than among men; higher in towns than in the countryside where, in many villages, even in western Europe, it might be only a handful beside the priest who could read a document or sign their names. Nothing in the records more poignantly suggests the powerlessness of the ordinary man, or the gulf that separated his world of custom and precedent from that of the lawyer or official, than the cross or token of calling, such as a roughly drawn pitchfork or hammer, appended to a register or deed upon which his livelihood might depend, but which he could not read. Braced, in the demonstrably unstable world of today, for constant change in all the relationships of life, the reader is asked to think about a life which had the stability of the patriarchal family and about an economy which was still based almost entirely on the domestic enterprise.

The family was the characteristic unit of the whole of life. Man today is taught, works and, in important respects, may virtually live in large concerns; he can hardly avoid to some extent deriving his values and tastes from mass markets and media. For the people of early modern Europe the big organization was exceptional: soldiers in an army, sailors on a big ship were out of the mainstream. Crowds were a rare and alarming experience; a popular rising was a departure from known, safe ways, and then all the more volatile and savage. To point to that humane and natural pattern of human activity, to stress the modest and intimate scale of existence, revolving round the family, extended as it might be by servants, apprentices or journeymen, is not to sentimentalize the past, but to provide a firm base for understanding it. In physical ways life was hazardous and death was a familiar guest, treated with perhaps less reserve and more resignation than in today’s more guarded and more private families. A bare three-quarters of children who survived childbirth would live for more than a year; a scratch or graze might bring death from blood poisoning. Epidemics served only to dramatize the normal condition of helplessness before the mysteries of contagion. Average life expectancy was around 25. Those few who grew old could expect an honoured position within three-generation families in a society which did not willingly reject or isolate the old.

In western Europe the Roman Church no longer enjoyed a monopoly. The seamless robe, the concept of universality, had been torn apart by the Reformation and the religious wars. There certainly existed various philosophic notions and moral codes that were classical, pagan or at least not specifically Christian. But the few among the élite of educated men who came under such influences still lived in a society which knew no sanctions as effective as those of Christianity. Among such people too, the vaguer but still potent sense of belonging to a common civilization lived on. The philosophe of the eighteenth century was as cosmopolitan in his outlook as the Christian humanist of the Renaissance period. For Voltaire, as it had been for Erasmus, Europe was the parish. Two giant cities, London and Paris, approaching half a million inhabitants by 1700, dominated the attitudes and tastes of the educated minority. They were exceeded only by Constantinople, its 800,000 feeding on the wealth of tributary lands, and otherwise approached only by Naples, with perhaps 400,000 living in its teeming streets. Other great cities, Rome, Warsaw, Dresden, Venice, Amsterdam, Madrid, soon significantly to be joined by St Petersburg as it rose from the swamps of the Neva, whatever the local variations, visibly belonged to the same high urban culture in which architecture, music and painting conformed to universal standards. At the level of the nobility, accepted conventions about dress, manners, ways of waging war, for instance, were more important than national differences. The nobility and gentry of Europe, together with those professional men and merchants who might be described as belonging to the political community, because they were in a position to make, influence or at least obstruct public policy, constituted groups that might vary in status, yet can be described collectively as a class, in the sense in which that word is now applied to ‘working’ or ‘middle’ class: a section of the community having a recognizable style of living, appearing to have certain common interests, and being capable of collective action in defence of those interests. In the case of the upper class of pre-industrial Europe, it is possible to identify and to analyse its position and values because they were affirmed with an unquestioning confidence in God-ordained rank and rights. Noble or bourgeois, they made ‘the history of events’ that provides the main themes of this book.

An Aristocratic Age

The continuing vitality of the aristocratic order, notwithstanding the advance of government, is an outstanding feature of the age. The master principle of government was the assertion of a single overriding authority above particular loyalties. Those tended to focus upon territorial magnates with rights and duties derived originally from the delegation of authority which had characterized the feudal state. Everywhere agents of the state had to contend with owners of fiefs and franchises who claimed as of right to be custodians of the rural masses. Acting corporately in estates and diets, those landowners strove to maintain their privileges. They were inclined to respect the principle of hierarchy, but not the demands of an impersonal state. They could be sure that the sovereign depended as much on them as they on him. On the one hand aspirants and creditors were pressing hard upon a class whose traditions left little room for development within the confines of a static rural economy: if it were to survive, the feudal nobility had to adapt. The state on the other hand had to work through the men who had the authority and means to enforce the law. For then, as now, it was impossible to control a society without the acquiescence of a ruling class.

What constituted nobility? It was a question much debated at the time. Men used words meaning broadly ‘noble’ or ‘gentleman’, besides terms to convey a specially lofty status, like the Spanish ‘grandee’, in a loose way that absolves us from the effort to define more precisely. Between countries there were huge differences. The class structure was generally simpler in the north and east than in the west. Bohemian, Prussian or Polish squires, exacting four days of demesne labour from peasants who were bound to the soil, lived in a different world from those of Sweden, whose lands were leased to tenant farmers, or even France, where rents, in one form or other, were more important than feudal services. The nobles of Sweden, hungry for employment and promotion in army and government, had little in common with those of Italy, who had for the most part no significant function. Russia was unique in this, as in most other respects. As a consequence of the dreadfully effective assault of Ivan IV (1547–84) upon the old landowning class and Peter I’s deliberate attempt to establish an aristocracy of service, culminating in his Table of Ranks (1722), there were no historic connections between particular families and estates, and no territorial titles. Even those two countries which seem to have had most in common, namely weak sovereigns, correspondingly influential magnates, and a numerous class of gentry richer in pride than in purse, afford extreme contrasts: the town-dwelling hidalgos of Spain were far removed from the ‘barefoot’ szlachta, whose white wooden farmhouses dotted the endless Polish plains.

Within...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- List of Maps

- Introduction to the 2003 Edition

- Preface

- Acknowledgement

- 1. The European World

- 2. Early Capitalism

- 3. God and Man

- 4. Adventures of Mind and Imagination

- 5. Questions of Authority

- 6. Diplomacy and War

- 7. Louis XIV’s France

- 8. Louis XV

- 9. Spain and Portugal

- 10. German Empire, Austrian State

- 11. The Rise of Prussia

- 12. Holland

- 13. Scandinavia

- 14. Poland

- 15. Russia

- 16. Russia After Peter

- 17. The Ottoman Empire