This is a test

- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Designing the City looks at current urban problems in cities and demonstrates how effective urban design can address social, economic and environmental issues as well as the physical planning at local level. The book is highly visual and illustrates the topic with a variety of sketches, line drawings, axonometrics and models. The author draws upon the valuable experience gained by the City of Glasgow and compares its solutions - successful and less successful - with projects in a variety of European countries.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Designing the City by Hildebrand Frey in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Urban Planning & Landscaping. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One: The Current Debate about the Sustainable City

1: What Urban Design Is and Why it is so Important Today

Urban design is a rather unfortunate term describing greatly confused responsibilities of people supposedly involved in the design of the city’s ‘public realm’. Urban design in the UK is a professional hybrid, a relatively recent invention intended to mediate between the responsibilities of urban and regional planners and architects.

A fruitful discussion of the enhancement of the physical form and spatial structure of the city must be based on a much clearer understanding of what urban design is or should be, what responsibilities it has or should have, and what its levels of intervention with the city are or should be. This first chapter develops a definition of urban design that results from an understanding of some problematic characteristics of form and structure of the city region, the city and its districts, all of which are believed to require urgent improvement.

1.1 What Urban Design is or What it Should Be

There seem to be as many definitions of urban design in the UK as there are urban designers. l shall not go into a detailed investigation, which has been done elsewhere (Madanipour, 1996), but almost all these definitions see urban design as bridging the gap between planning and architecture. In the 1960s these two disciplines ‘most immediately concerned with the design of the urban environment’ (Gosling and Maitland, 1984, p. 7) decided to split. They developed separate university courses, with planning focusing on land-use patterns and socio-economic issues and architecture on the design of buildings. The gap of responsibilities between the two disciplines soon became apparent and urban design came into existence as an attempt to cover issues for which neither planning nor architecture claimed responsibility: the design of public spaces.

Urban Design In The UK: The Theory

The frequently adopted definition of urban design is thatit is

concerned with the physical form of the public realm over a limited physical area of the city and that it therefore lies between the two well-established design scales of architecture, which is concerned with the physical form of the private realm of the individual building, and town and regional planning, which is concerned with the organisation of the public realm in its wider context

(Gosling and Maitland, 1984, p. 9)

There are problems with this definition. One is that it does not seem to recognise that much of what is called the ‘public realm’, the city’s public streets and squares, is actually physically bounded by elements of the ‘private realm’, by private buildings. The design of streets and squares cannot ignore the design features of those private buildings that form the edges of these spaces. Urban design, though primarily responsible for the design of public streets and squares, must therefore set at least some rules for the design of those elements of the private realm that are involved in the formation of the public realm. Simiiarly, parts of the city’s public realm, the public buildings and monuments, are designed not by the urban designer but by the architect. And this makes matters more complicated because inevitably the urban designer’s responsibility overlaps at the micro-scale of operations with that of the architect, as the architect’s does with that of the urban designer.

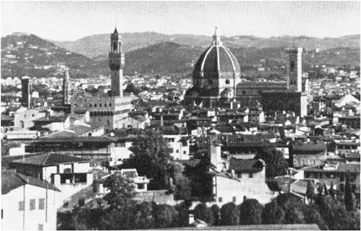

Another problem with this definition is that it does not specify what the ‘public realm’ is. In the traditional city the public realm, which Leon Krier called ‘Res Publica’, includes all public monuments, halls, memorials and public works the vertical features of which shape the city’s skyline, as well as all major public streets and squares that link these urban components or front them (see Papadakis, 1984, pp. 40–1). These components of the public realm are embedded within the fabric of the private realm, called by Leon Krier ‘Res (Economica) Privata’, which provides accommodation for living, production, administration, commerce, storage, health care, defence and security, and which, in relationship to the public realm, is in the traditional city subordinate to the public realm and forms the city’s horizontal mass (Fig. 1.01).

This distinction is useful and illustrates that not all public spaces are of the same importance; some may have only local, others district- or even city-wide significance. And the same differentiation of importance must be made for urban monuments. Urban design should respond to the distinction between more or less important components of the city, between those that are long-lasting, structure-generating and form-giving for the city (or urban districts) at large and others that may be modified as a consequence of socio-economic changes and are therefore less significant with regard to the city’s form and structure. But if this distinction is adopted then the restriction of the responsibility of urban design to a ‘limited physical area of the city’, as defined above, becomes rather problematic because it precludes urban design from having a holistic view of the city, which then only urban planning would have. But adopting a holistic view makes matters even more complicated because it causes the urban designer’s responsibility to overlap at the macro-scale of operations with that of the urban planner.

Consequently, the amenability of urban design can neither be restricted to the elements of the public realm only, much of which is bounded by elements of the private realm, nor be restricted to a limited physical area of the city because then it would be ineffective in the shaping of the city’s and its districts’ physical form and skyline and their spatial structure. Urban design therefore does not fit neatly in between the responsibilities and activities of urban and regional planning and architecture; its responsibilities overlap considerably with the concerns of both disciplines.

Urban Design In The UK: The Practice

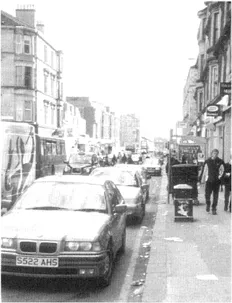

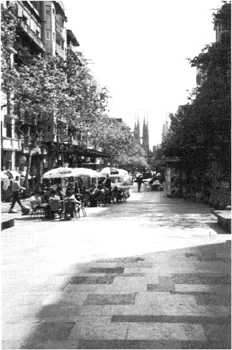

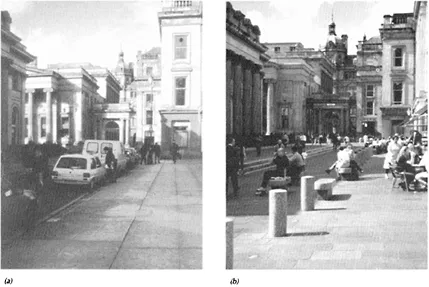

The run-down state of many of the UK’s cities’ public streets and squares, even those of major importance, seems to indicate that there is very little care for, let alone design of, the public realm (Fig. 1.02). In contrast, a city like Barcelona, for instance, illustrates a great concern for the quality of public streets and squares which are co-ordinated to form an urban network and designed and executed to a high standard (Fig. 1.03). There are always notable exceptions, but generally there seems to be very little urban design of that kind in the UK’s cities.

1–01. The public and the private realm of the city illustrated by the skyline of central Florence

Because of the lack of a common definition, there are many different kinds of urban projects which are claimed to fall into the category of urban design. There are many theoretical but rather fewer real examples of urban design which deal with development pattern, spatial structure and physical form of specific urban areas, mostly relatively small in dimensions, very much in tune with the generally adopted view of the nature of urban design and focusing on the improvement of the public realm. Typical examples of such design projects emerged, for instance, from the ‘Quality in Town and Country’ Initiative, launched by the Secretary of State in 1994 (DoE, 1994), a key stage of which culminated in the exhibition of 21 case studies from different parts of the UK with the focus on the creation of a sense of place, identity and civic pride through new development (DoE, 1996). Another typical example of this kind of urban design is the plan for the regeneration of the bomb-damaged area in the city centre of Manchester. Manchester City Council promoted an international competition to redefine the city centre and this resulted in a master plan (Manchester Millennium, 1996) and supplementary planning guidance for the area (Manchester City Council, 1996).

Otherwise, many of the other UK projects called urban design fall into two categories: they are either architectural master-planning, i.e. the design of large-scale and almost exclusively private architectural projects rather than the design of public streets and squares, or they are the largely cosmetic treatment of individual public spaces. Two examples can easily illustrate this.

1–02. Byres Road, Glasgow

The Canary Wharf project in London’s Docklands is a large architectural project developed on the basis of a master plan for a group of buildings along a central axis, designed in minute detail for one developer by a small number of architectural firms (Fig. 1.04). The major central axis is not really a public street but, rather like the mall in a shopping complex, private and accord demonstrates international speculative forces at work. To express their ranking in the hierarchy of importance of such forces, the project applies a monumental scale and architectural language for publicly less significant elements of the private economic realm. We may have become used to the ‘cathedrals of commerce’ in the ‘city’, but what remains frequently unexplored in such large-scale architectural projects—and Canary Wharf is no exception—is their relationship to the urban context. They frequently fail to link into and enhance the structure, morphology and use pattern of an urban district. The fact that many such projects ignore the urban context and the people living and working around them illustrates the ‘architectural’ and private nature of such development rather than the concern for the public realm and the quality of an urban district for the inhabitants.

1–03. Avinguda de Gaudí, Barcelona

1–05. Royal Exchange Square, Glasgow. (a) The square before refurbishment; (b) the square after refurbishment in 1997

The other kind of ‘urban design’ practised in the UK is the cosmetic treatment of existing streets and squares, limited betterment of hard and soft landscaping as demonstrated, for instance, in the ‘Great Streets’ project in Glasgow (Fig. 1.05a, b). Useful as such improvement may be for a particular public space, it is in the end fully effective only if it represents part of a much wider plan, say of the promotion of the network of important public spaces of an entire district, without which it remains an isolated event. Though this point, which will be returned to later, is rather obvious, urban design in the UK that actually deals with the public realm is generally limited to individual and disparate spaces: it improves a particular place but very rarely has a strategic dimension as long as it fails to be part of a district- or city-wide advancement plan.

Projects of both categories may indeed achieve important local development and advancement but, because they are not co-ordinated and orchestrated, they do not add up to more than the sum of their parts and the city remains a more or less chaotic patchwork (Fig. 1.06).

Urban Design in Other European Countries and Cities

In the UK, planning has largely abolished the responsibility for the physical form of the city and its districts. Development control, the responsibility of planning, is generally based on two-dimensional structure plans focusing on land-use patterns and socioeconomic issues, and predominantly two-dimensional local plans dealing with problems and opportunities of a specific urban area or district. Local plans may be supported by design guidelines but they are usually general rather than place specific; that is, they frequently do not distinguish between more and less important components of the public and private realm.

1–06. The Scottish Exhibition and Conference Centre, Glasgow, seen across what was the Garden Festival site

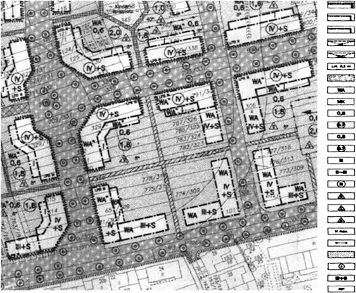

It is interesting to observe that in the German-speaking countries of Europe, for instance, urban planning has remained much closer to architecture than in the UK. Many, if not the majority, of planning courses remain integrated in schools of architecture, with planning at such schools being seen as a field of specialisation growing out of an architectural education. Therefore it is not surprising that in these countries development and control of the physical form of the city remains an integrated part of urban development control (see Pantel, 1994). In addition to structure and local plans, they operate with what they call Bebauungspläne, plans regulating not only the land use but also the built form of streets, squares, districts and the city (Fig. 1.07). It might be appropriate to call such plans ‘urban design frameworks’.

The degree to which such Bebauungspläne regulate the physical form of development depends on the importance of individual places or districts for the city. Design rules may be stringent for significant places and areas, prescribing even small details of physical development, maybe including the detailing of facades and the formation of the roofs of buildings; or they may be rather relaxed for less significant places, prescribing only the overall massing of development or leaving it entirely open and restricting perhaps only the height of development. A set of such Bebauungspläne may therefore be orchestrated to control the important features, places and districts of a city and to grant relative freedom for development in the less important areas. Very frequently details of Bebauungspläne are the result of design competitions as the well-documented Berlin IBA experience demonstrates (IBA Berlin, AR September 1984; AR April 1987; IBA 1984, 1981). And whereas in the UK structure and local plans represent guidelines, those in the German-speaking countries, including the Bebauungspläne, once passed by local council or government, have legal status and represent a very powerful means of urban development control.

1–07. Example of a Bebauungsplan: a housing scheme in Frankfurt am Main

The Question of Over- or Under-regulating Urban Development

One may argue that over-regulating urban development by means of something like a Bebauungsplan will not only be counter-productive in development terms, for instance scaring away developers, but will generate a mediocre, if not monotonous, urban environment, lacking formal variety and design ingenuity which is stifled by excessively tight rules (Fig. 1.08a). Well, this may be true in some cases, but compare the results of under-regulating urban development, which invites idiosyncratic projects and brings little if any co-ordination (Fig. 1.08b).

Any approach is only as good as its implementation, and the question is not whether or not there should be any urban design frameworks for the co-ordination of the physical form of urban development but what form of urban design framework and what degree of co-ordination is applied and for which areas or places in the city. The city as a physical entity is composed of many different elements which relate to each other functionally and spatially. Just as a pile of parts becomes a well-functioning car only when arranged in the right functional and spatial order, so disparate urban elements crea...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part One: The Current Debate about the Sustainable City

- Part Two: Application of the Model Urban Structure to Glasgow

- Epilogue