- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

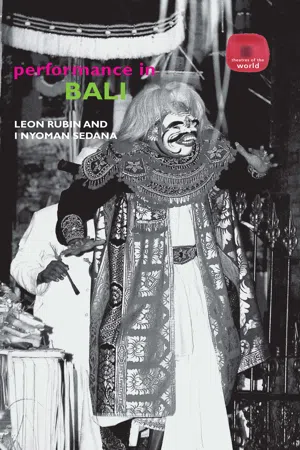

Performance in Bali

About this book

Leon Rubin and I Nyoman Sedana, both international theatre professionals as well as scholars, collaborate to give an understanding of performance culture in Bali from inside and out.

The book describes four specific forms of contemporary performance that are unique to Bali:

- Wayang shadow-puppet theatre

- Sanghyang ritual trance performance

- Gambuh classical dance-drama

- the virtuoso art of Topeng masked theatre.

These culturally unique and beautiful theatrical events are contextualised within religious, intellectual and social backgrounds to give unparalleled insight into the mind and world of the Balinese performer.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Past and present

When the bomb exploded in the Sari Club in Legian Street, Kuta, Bali on 12 October 2002, a wave of anguish swept through Balinese life. Although, over the centuries, Bali had not been immune to great pain, violence and suffering, recent times had been peaceful and relatively prosperous within economically struggling Indonesia. The development of tourism through the 1980s and 1990s had generally established a peaceful life for most inhabitants. The bombing by Muslim extremists shattered that peace in many ways that are not all evident to the outsider. The bombing affected various levels of Balinese society, from the financial and political to the religious, cultural and philosophical. It was to the people of Bali as though the delicate and harmonious balance between good and evil had been destroyed. In the Balinese way of seeing the universe, good and evil always coexist. Throughout Balinese art, religion and philosophy there is constant reference to this idea of a balanced universe that recognises the existence of both forces, rwa bhineda. Unlike the dominant, simplistic Western concept of the need to defeat evil and divide the world between the good guys and the villains, the Balinese view is that evil spirits exist and that you need to deal with them, appease them, pacify them, distract them or transform them into good spirits, but you never defeat them. When an imbalance occurs and evil is strong in the world, you must create more good to regain the balance, and so goodness, temple ceremonies and religious duty to the community must all be increased as a response.

Most performance forms in Bali, apart from the completely secular, deal at some point with this fact of existence as part of the rituals with which they are connected. In response to the bomb outrage, many performances took place all over the island to amend the imbalance that had been caused. The evil spirits were dominating and had to be pacified and harmony had to be restored. Some of these performances were well documented in articles by academic observers as the extraordinary manifestation of art as a weapon against violence unfolded. Of course, the conventional military and police responses took place simultaneously, but the purification rituals of performances were considered as potent and important. Culture is a weapon in Bali (Jenkins and Catra, 2004:71) and has historically been an important part of a defence strategy against the outside world. It is the powerful and enduring sense of cultural identity that has helped defend Bali from outside forces over the centuries. Bali is still the last tiny island that resisted the Muslim advance across Asia; the sweep across the Indonesian islands was stopped dead there. The remaining key Majapahit elite fled to join their relatives in Bali, as it was the region’s final Hindu outpost of a lost culture. By the early sixteenth century, all Buddhist/Hindu areas had almost completely disappeared throughout what is now known as Indonesia, and Bali was the only remaining entity. The Majapahit Empire, itself a complex mixture of Buddhist and Hindu culture, had conquered Bali as early as 1343 and brought with it Buddhist and Hindu/Shiwa-related religion. It also brought the Ramayana and Mahabharata and the religious, philosophical and performance traditions. They integrated with the existing traditions to produce the rich culture that are present today.

When the Dutch empire colonised the region (finally achieved in 1891, after 50 years of treaties and battles), Bali offered the strongest resistance, including mass suicide (known in the history books as puputan), in the face of superior weaponry and a war that was impossible to win. The resistance was not just for the sake of political independence; the Balinese people also resisted because of a passionate desire to protect a deeply ingrained culture. When the Japanese invaded Bali, landing in Sanur on 18 February 1942, during World War II, many Balinese intellectuals and others welcomed the Japanese as an Asian controlling force that they thought would be more in sympathy with Balinese ideals; however, by the end period of the war they understood this was not the way Japanese rule worked. Although in the first period after the invasion the new colonial rulers were indeed sympathetic to Balinese social structures and culture, this sympathy fell away as the war turned against Japan and a much harsher rule took over.

Even the Dutch rulers recognised the unique exquisiteness of Balinese cultural identity and took steps to help preserve it, although their intentions were to keep Bali as a paradise island that was suitable for wealthy Dutch tourists. Numerous artists and anthropologists who made the pilgrimage to Bali popularised this exotic and mysterious paradise during the 1920s and 1930s. They wrote about and visually depicted the great culture from the past that still survived. The colonial implication existed that this was a fascinating but ultimately naïve and early civilisation clearly inferior to the modern European cultural environment. However, the Balinese, typically, learnt new ideas and skills from their foreign visitors/rulers and created numerous new styles and forms of visual and performing arts that retained a powerful, central Balinese consciousness. The new forms did not replace but sat side by side with the traditional forms. Most tourists today witnessing the Kecak dance, performed daily for tourists, are blissfully unaware that the traditional, ancient ceremony/performance they are attending was choreographed by the German artist and chorographer Walter Spies in the 1920s, and that it was based on mixing together bits of different existing forms. The Balinese do not fear the present invasion of foreign tourists (that began during the Dutch rule and has mushroomed in recent years) because they possess an intense cultural confidence that permeates throughout their society. The Balinese people generally welcome, rather than reject, foreign influences and in some cases adopt them within their own sensibilities. They do not have the fear of losing their identity that is so common in many other cultures faced with overwhelming influences from globalisation. This ability to accept and adapt outside cultural influences alongside traditional Balinese arts and culture is explored throughout this book.

The purification ceremonies and performances stressed the need for the Balinese people to remember the lessons of the past – adhering to traditional principles of good behaviour, tolerance, community spirit and generosity had helped them recover from times of disaster and conflict. The Balinese retold stories that were both comic and deeply serious within various forms of drama. These stories served as reminders of their principles as they attempted to rebalance the harmony between good and evil. The possible hostile reaction towards Muslims did not materialise, and therefore the circles of revenge/hatred were not fuelled, in spite of the deliberate provocation. The Balinese were well aware that Bali had been targeted because it was a non-Muslim culture and was a doorway to the outside world.

These unique cultural responses to the bombing show many of the elements of Balinese life and thought that are at the heart of performance culture on the island. The focus on good and evil and balance is connected to many aspects of Balinese life. Evil spirits, butha, are represented in architectural relief, painting and performance masks. The Balinese believe the spirits are close to the ground or beneath the ground and always think of them in that context. Evil spirits can also be understood in more abstract ways – to many Balinese we have within us good and evil, manifested in mood and action, and this, too, is part of the universal balance between the two extremes. On the night before the lunar New Year, Nyepi, parades of huge effigies of the Butha Kala, the evil earth spirits, take place across Bali. People within each community create the figures, Ogoh Ogoh, some over ten metres high. Accompanied by firecrackers and banging of instruments and other objects, the Balinese parade the effigies through the villages to the seashore where they are generally burned. The idea is to show what the Butha Kala are like and then to distract them as they follow the giant effigies and parade them away from the humans to the sea. Then, the next day, Nyepi, there is a day of silence throughout Bali. No one, not even tourists, is allowed out on the streets and electricity should not be used, even for lighting. An extraordinary silence and calm descends on the island from dawn until dawn the next day. The day of silence allows people to think about themselves and the past year and to reflect on how they should behave in the year to come. Some believe that the silence and darkness is to fool the Butha Kala into thinking that the island is uninhabited so they will fly away, but it is generally believed that it is a time to celebrate and relax after the spirits have gone away, at least for a while. This showing and placating of evil spirits is very present in many performance forms, including Sanghyang, Topeng and Wayang. In each case, the battles between good and evil and the restoration of balance at the end are strongly evident in the content and structure of the forms. Even in the best-known performance ritual battle between the Barong, a mythical creature who protects the villagers, and Rangda, the evil witch who threatens them, the performance culminates in the defeat of Rangda. She is not killed onstage but retreats offstage, weakened and unable to continue the fight. However, all the audience know that the victory is temporary and she will return another day. A simple resolution does not exist to the eternal conflict between good and evil.

The Ogoh Ogoh effigies also demonstrate another key aspect of Balinese performance and religious philosophy that concerns balance in another way: physical states of balance. Each dancing figure produces a kinaesthetic response to the observer, as though moving in space as it is carried along. One leg is usually raised and one arm is higher than the other to compensate and to bring the effigy into balance. These enormous figures seem light and in motion. This design is created deliberately to suggest this feeling of balance. All Balinese dance and dance-drama forms start with the same physical premise, as the performers constantly move from one side to the other and up and down finding points of balance, even as those points move elusively away. In this way, the dance continues as though the performer is almost falling from one position to another, rarely holding a point of balance but moving through it to the next. This constant motion and energy lies at the heart of Balinese performance and simultaneously relates to the more philosophical ideals of universal balance.

The concept of motion is also seen in the frequent reference in Balinese culture to the symbol of the swastika. Although in the West the crime of desecrating an important religious symbol can be added to the other Nazi war crimes, in Bali it remains sacred. The swastika is one of the oldest symbols known to man and has traceable origins back more than 3,000 years. It has been found in almost every major culture of the world and has different

Figure 1.1 Figures from the Ogoh Ogoh parade

meanings associated with it accordingly. However, in particular, it is sacred to both the religious cultures that dominate Balinese perceptions about art and philosophy – Hinduism and Buddhism. A number of connotations inform the understanding of the swastika to many Balinese and how it connects to performance. The first recorded use of the word itself is in the two epics the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. The word swastika is derived from Sanskrit and different commentators explain its meaning in various ways. Most agree it indicates the idea of ‘good’ or ‘goodness’ from the root su and ‘existence’ or ‘being’ from the root word, asti. So, it is associated with good luck, eternity and well-being. The swastika is found frequently throughout the Hindu world, in particular adorning buildings and objects. In Bali, it can also be found in connection with cremation and suggests reincarnation and the circles of existence close to Hindu and Buddhist thought. Other symbolic associations relate to the visual make-up of this intriguing symbol, and some Balinese believe these are adopted into an understanding of performance theory. As an ideogram, the swastika has specific purposes imbedded within it and the symbol’s design is important. It can be looked at as a type of cross with the four central lines seen as indicators of North, South, East and West and the additional extending arms from each of these lines as indicators of the four remaining directions, North East, North West, South East and South West. In Balinese thought, these directions all have detailed meanings and connotations relating to religious concepts, and these concepts are frequently referred to in all Balinese art forms. In addition, the swastika suggests the idea of up and down and centre. The symbol also represents the central concept of balance and harmony as each section stands in opposition to another. So, it is often understood as representing good and evil, positive and negative, strong and weak, etc. It appears to be like a wheel, forever moving forward and rotating and is thought to be associated with an image of the sun (again suggesting life-force) and possibly a comet. No matter what the interpretation, the idea of powerful motion is important in relation to Balinese performance. Some...

Table of contents

- Theatres of the World

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Past and present

- 2 Wayang shadow theatre

- 3 Sanghyang trance performance

- 4 Gambuh classical performance

- 5 Topeng masked theatre

- 6 The future

- Travel advisory

- Glossary

- Selected bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Performance in Bali by Leon Rubin,I. Nyoman Sedana,I Nyoman Sedana in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Performing Arts. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.