![]()

1

GLOBALIZATION AND THE ECONOMICS OF RADICAL CHANGE IN CHINA

A Place of Radical Change

Shanghai, 2011—standing on Shanghai’s Bund, overlooking the Huangpu River, one cannot help but see how dramatic the changes have been in China in the last two decades. Especially in the evening. Neon signs light up the night sky; strobe lights dance across the river, as if to announce the arrival of the new city. Nouveau riche couples dining at the swanky restaurants, like M on the Bund, overlook this panorama and enjoy a nightlife scene that might place them in London, New York City, or Paris. Across the river, an entirely new skyline has emerged from virtually nothing: In the early 1990s, when I started doing research on China, Pudong (the area east of the Huangpu River) was an area of fields and old housing projects; today it is a high-tech urban landscape with immaculate and gaudy buildings that touch the sky, including one of the tallest buildings in the world. The scene is eerily reminiscent of a futuristic science fiction movie. These days, when I give talks about China’s emergence as a global economic superpower, I often invoke the contrast between what the skyline looks like today and what it looked like eighteen years ago. Those stories seem more and more distant today, but it is still less than two decades ago that Pudong was not even on the map in terms of infrastructure or economic development; today it is emerging as a financial center of Asia if not the world.

Other places in China also show the signs of extreme change. The Beijing skyline lacks the panache of Shanghai’s “Bund” (the area along the western side of the Huangpu River), but the changes occurring there are no less dramatic. In Beijing, cranes dot the skyline of the city’s sprawling urban landscape; the immaculate architectural feats constructed for the 2008 Olympics are always around the next corner; fast food restaurants and Starbucks stores buttress up against the borders of the Forbidden City and Tiananmen Square; skyscrapers have been built upon the wreckage of Beijing’s old urban neighborhood blocks. In western Chinese cities like Chengdu and Chongqing, China’s most populous city, signs of urban development are everywhere as well. And in smaller towns in rural areas, new buildings run up against small houses made of straw-and-mud bricks.

The scenes are breathtaking, even to those unfamiliar with urban development and architectural planning. They are also clearly—even to the untrained eye—tied to foreign investment, economic reform, and the complex processes of globalization. Across the Shanghai skyline, for every neon sign advertising a Chinese company, you will also see the logo of a foreign multinational. The Motorola name is as well known as that of the famous Chinese telecommunications company, Huawei; DuPont is among the most well-known names in areas ranging from chemicals to renewable energy; most cabs are made by a joint venture corporation backed by Volkswagen; most luxury cars made by Audi, GM (Buick), and BMW; brands like Coca-Cola, McDonald’s, Kentucky Fried Chicken, Pizza Hut, and Starbucks are ubiquitous. At the same time, powerful Chinese domestic multinationals such as Geely, Haier, Lenovo, PetroChina, Huawei and SinoPec are shaking the world with their own economic power.

All of these facts and images are, by now, well known. Indeed, the headlines announcing “China’s Century,” “The China Challenge,” “The China Syndrome,” “Buying up the World,” “America’s Fear of China,” “China Goes Shopping,” “Can China be Fixed?” and many others, have thundered across the covers of such magazines as BusinessWeek, the Economist, Forbes, Newsweek, U.S. News and World Report, and many other major publications. However, if the fact of China’s emergence as an economic and political superpower today is widely recognized, the processes by which we have arrived at this moment in time are less clear. What global and local processes lie beneath the dramatic transformation we have witnessed over the last quarter century in China? What are the political, economic, and social forces that have shaped the Shanghai, Beijing, and Chengdu skylines? And what impact do competing foreign and Chinese national interests have on the citizens of China and on the rest of the world? The story that lies beneath is one of deep-seated national interests of the world’s most populous nation as it gradually edges its way down the path of economic reform toward the hallowed land of capitalism; and of foreign investors that seek access to the world’s largest single-nation marketplace. It is a story of the forces of globalization, played out locally; a story of the complex political situation that saw a dying Communist regime transform itself, in part, by allowing foreign multinationals to set up shop in China for the first time since the Communist Revolution. Uncovering these forces and trends is the purpose of this book.

The Emergence of China as a World Economic Power

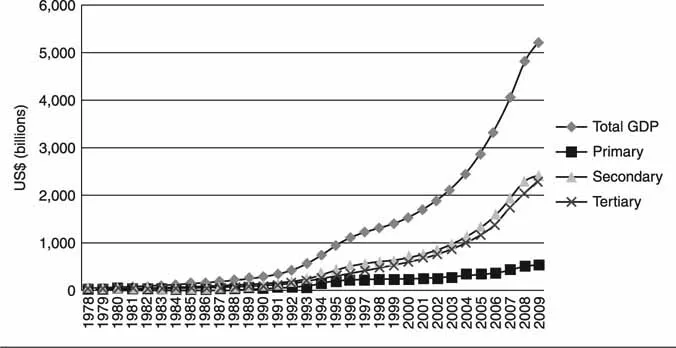

There are many reasons why we should develop an informed understanding of the state of affairs in Chinese society. Not only is China the most populous nation on earth, but it has also, in recent years, stormed onto the world political and economic stages. The country has accomplished in three decades what many developing nations have taken half a century or more to achieve. For the better part of the last 30 years, China has had the fastest growing economy in the world, sustaining impressive double-digit growth for much of the 1980s and 1990s and high single-digit growth for the 2000s. Throughout the 1980s, China’s real gross domestic product (GDP) grew at an average annual rate of 10.2 percent, a level that was only equaled by the growth rate in Botswana (and it is much more common for small countries like Botswana to achieve such high growth rates). From 1990 to 1996, the average annual rate of growth for real GDP was 12.3 percent, the highest rate of any country in the world for that period. It has also had the highest industrial growth rate (an amazing 17.3 percent average annual growth from 1990 to 1996) and the second-highest growth in services (9.6 percent per annum, 1990–1996) in the world (World in Figures 1999, 2010). It is an understatement to say that China’s economic reforms have been a remarkable and dramatic success. Table 1.1 shows how China compares with the countries that are generally considered to be the top ten economies in the world, according to various economic indicators. Where China was a third-world developing economy three short decades ago, today it has the second-largest economy in the world overall in terms of GDP, and it is second to the United States when GDP is adjusted for purchasing power within the country.1 To the extent that economic and political power are intimately intertwined, China’s sizable role as a political force on the world stage is all but guaranteed. It is no longer a question of whether China is going to play a major role in world economic and political arenas; it is only a question of what role China will play.

Table 1.1 Largest Economies in the World According to Various Economic Indicators

Source: Pocket World in Figures (2011, 14, 24, 46, 47, 68)

The emergence of China as a world economic and political power has serious consequences for the structure of relations in Asia and for the global economy in general. If the twenty-first century will be Asia’s century, as many scholars and pundits have predicted, then China is certain to be the major player in a region that is sure to play a definitive role in the current century. And this lumbering giant has only begun to flex its political and economic muscle. However, because of its size, China’s role in the coming years is almost certain to have greater gravity than would be suggested by simply acknowledging its position as a leader in a pivotal region. Take, for example, food: because of the loss of crop land that comes with rapid industrialization and a still-growing population in China (despite austere family-planning measures), some estimates suggest that China currently cannot produce enough food to feed its citizens. These same estimates suggest that, at current rates of growth, all the excess in the world’s grain markets will not meet China’s needs by the year 2030.2 So here we have a country that rose in three decades to be the second-largest economy in the world—a country that could very well cripple international grain markets and have a large starving population before the middle of the twenty-first century. As another example, consider information technology: based on the size of China’s population and recent developments in the country’s telecommunications sector, China is now the single largest market for Internet and telecommunications use in the entire world. Here again, we have the strange paradox of development in China: as the country struggles with the basic developmental tasks of laying phone lines and building roads, it threatens to be the crucial market in driving the evolution of one of the most important industries in the global economy. Then there is the issue of oil and energy: China’s rapid economic development has led to an insatiable thirst for energy and, more specifically, fossil fuels. With its consumption more than doubling over the last five years, China sits behind only the United States as the second-largest consumer of oil in the world.3 The high demand for oil has contributed to rising rates of oil prices, which have hit record highs in cost per barrel in recent years, a fact that affects American consumers with higher gas prices. Another important, though less understood, issue involves China’s influence over the U.S. bond market. China is now the largest foreign holder of U.S. Treasury bonds. People frequently point to the oft-decried trade deficit between the United States and China, but China’s rapid purchase of U.S. Treasury bonds in recent years is a much more significant factor in U.S.–China economic interdependence. If the People’s Bank of China decided to begin dumping U.S. Treasury bonds, the effects could have a devastating impact on the already weakening U.S. economy. In all of these issues and many others, the simple fact is that understanding China’s role in the world economy and how this country has arrived at its current position is imperative to an understanding of global economic and political trends as well as the interrelated nature of political, economic, and social change in developing economies.

Figure 1.1 GDP Growth in China 1978–2009.

Source: National Statistical Bureau of China (2010, 38).

Yet, while China’s rise in power over the last three decades has been meteoric—and we are only beginning to feel the impact of that rise in power—our understanding of the changes that have occurred there lags far behind the reality. Many current views of China fail to grasp the depth and magnitude of the reforms, and we have even less understanding of the forces and processes that have wrought these changes. To some observers, China has succeeded in spite of the state’s continuing presence as an authoritarian government. Indeed, some observers view China’s current situation as quite tenuous precisely because of the partial and political nature of the reforms. In one example, Gordon Chang’s famous screed, The Coming Collapse of China, warned, “Beneath the surface … there is a weak China, one that is in long-term decline and even on the verge of collapse. The symptoms of decay are to be seen everywhere.” More recently, investors like James Chanos, who prophetically predicted the fall of Enron (and made a lot of money shorting the company), has also predicted the coming collapse of the world’s fastest rising economy.4

Many of the critiques of China focus on what is viewed as an over-bearing and corrupt state. The general argument is that, because China has not embraced the tenets of a Western-style free market, it simply cannot succeed in building a healthy market economy. However, China’s dramatic success in economic reform has been precisely because of the state’s participation in the process. Its emergence as an economic juggernaut has been the result of methodical and careful government policies that have gradually created a market economy in a stable fashion. An examination of China’s reform effort gives rise to issues and questions that are fundamental to a full understanding of the global economic system: what is the current state of economic, political, and social reform in China, and to what extent are these realms inextricably intertwined in China’s course of development? What are the forces that have given rise to the radical changes occurring in China? How are these changes related to the global economy? What does this process tell us about the transition from communism to capitalism, a process in which several countries in the world are currently engaged? How have the economic changes that have occurred in China over the last three decades influenced the lives of people there? What does a close examination of the process of change in China tell us about the prospects for the emergence of democratic institutions there? And, finally, what do these changes tell us about the way we choose to govern the US economy?

In addressing these questions, I take two basic positions in this book. First, the stunning success of China turns some key assumptions of economic theory on their heads. The case of China gives clear evidence that rapid privatization is not a necessary part of a transition to a market economy and, by extension, that private property is not a necessary cornerstone of a functioning market economy. There are many different ways to create the incentives that govern a healthy economy, and private property is but one of them. This is not only an issue of theoretical concern. Important institutions such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) have long been guided by the arguments for rapid privatization and, in many cases, they have forced these policies on developing nations. Second, democracy is an inevitability in China. The basic argument here is that capitalism and democracy are systems that must be learned over time. Thus, where rapid transitions to either system often invite chaos, gradual transitions allow for the stable emergence of new institutions and systems. More to the point, China has been gradually developing the institutions of democracy. The ideological war between reformers and hard-liners has forced the former group to transform China’s institutions without labeling them as a transition to democracy.

Globalization and the Transition to Capitalism in China

This book is a general introduction to the process of economic change that has occurred in China since the country’s economic reforms began in 1979. As many parts of society are shaped by, and intersect with, the economy, I explore different aspects of the ways that life has changed in China in the reform era. Before I dive into substance, however, it is useful to begin with a brief discussion of the theoretical edifice that will guide my analyses of economic and social change. There are a number of different ways to think about economic change. In this book, I begin with a political–cultural approach to understanding globalization, economic institutions, and social change. Economic institutions and practices are deeply embedded in political, cultural, and social systems, and it is impossible to analyze the economy without analyzing the ways that it is shaped by politics, culture, and the social world. This perspective is essential for understanding the complex process of economic and social reform in any transforming society, but it is especially critical for understanding China’s reform path and trajectory. This position may seem obvious to some, but it is important to note that, for years, economists from the World Bank, the IMF, and various reaches of academia have operated from a different set of assumptions: they assumed that a transition to markets is a simple and, basically, apolitical process. As Jeffrey Sachs, one of the world’s most influential economists in the study of transforming economies in the 1980s and 1990s, and his co-author, Wing Thye Woo (1997), once quipped, “The long-run goals of institutional change are clear, and are found in the economic models of existing market-based economies.” In other words, don’t worry about the complexities of culture or preexisting social or political systems; if you put the right capitalist institutions in place (i.e., private property), transition to a market economy will be a simple process (see also Sachs 1992, 1993, 1995b; Woo et al. 1993, 1997; Sachs and Lipton 1990; Woo 1997, 1999; Barro and Sala-i-Martin 1995; Blanchard et al. 1993; Fischer 1992; Fischer and Gelb 1991).5 The perspective I present here is that the standard economic view of market transitions that defined a good deal of policy in the 1990s could not be more simplistic or more wrong. In the sections that follow, I briefly discuss the ways that politics, culture, and the social world will play into the analysis of China’s transition to a market economy presented throughout these chapters.

The Politics of Market Reform

Beginning with Hungary in the 1960s, many communist countries have embarked on the path of transition from planned to market economic systems. Understanding the paths of transition from socialism to capitalism is a complex task, but it is also an important one, as this process opens up questions about the nature of markets, the nature of economic systems, and the extent to which markets and economic systems are embedded in political and social worlds. Research on transforming socialist economies has given rise to two basic views of economic change in these societies. On one side of the fence sit those scholars (cited above) who believe that markets operate primarily, if not solely, through private interests and individual incentives, and that market economies are built upon the foundation of private ownership and incentives. Given that communist-planned economies are basically organized around state ownership—an institutional arrangement that often leads to many distortions in terms of market relationships—those from the privatization school believe that rapid privatization is the only viable path of transition from planned to market economies. Rapid privatization, which can create an extreme “shock” to the society undergoing such a transition, has accordingly been given such labels as “shock therapy” and the “big bang approach” to economic reform. The approaches adopted in countries such as Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, and Russia fit this model of economic reform.

A second school of researchers—which includes scholars such as Barry Naughton (1995, 2007), Thomas Rawski (1994, 1995, 1999), Andrew Walder (1995a, 1995b), Jean Oi (1989, 1992, 1995), and myself (Guthrie 1997, 1999)—argues that markets are fundamentally political, social, and cultural systems, and a stable transition to a capitalist system must occur in a gradual fashion, with significant and constant support and guidance from the state. Market institutions and the economic practices that individuals and organizations adopt cannot be reduced to a simple equation of private interests and the individual pursuit of profits. The political, cultural, and social forces to which market institutions are subject are simply too powerful to ignore, so economic change must move forward in a slow, incremental fashion. The strategies of reform that arise from this view of economic systems see the state as a critical player in the transition to a market economic system. As practitioners, the architects of the Chinese reforms have embraced the gradualist view, and it has led to a gradual and stable path through the economic reforms. Furthermore, the dramatic success of the first three decades of reform in China (compared with the turmoil caused by rapid reform programs in countries such as Russia) raises serious doubts about the shock therapy approach and the economic assumptions that undergird that view. In many ways, by spurning the views of Western economic advisors and then gradually piecing together the most successful reform process of any transforming planned economy, China has served as the strongest indictment of the simpleminded nature of the market-driven economic logic of the rapid privatization school.

At the center of the tension between these two schools of economic reform is a debate over the role of the state in the construction and maintenance of new markets and the extent to which economic processes are fundamentally political processes. China’s reform process serves as a perfect example of the extent to which economic development and transitions to capitalism are, indeed, polit...