![]()

Part I

The Learning School

![]()

1

The story begins

John MacBeath and Stewart Hay

The Learning School

• Teams of school students from five (year 1) to eight (year 3) countries

• Visiting schools in each of those countries

• Spending up to 6 weeks in each school

• Living with host families

• Using tools to evaluate learning, motivation, self-evaluation

• Feeding back results to the teachers and management

• Presenting findings to policy-makers, academics, international conferences

• Three successive cohorts (LS1, LS2, LS3) revisiting schools with new research themes, new challenges

Stories come in different shapes. There are stories told objectively by authors, omniscient people who perch above the narrative and give themselves licence to intrude into every private space, even into their character's deepest thoughts and feelings, admitting no ambiguity because they have assumed an unquestioned authority as to what actually happened. Then there are those more modest authors who tell their story from a singular point of view. They can only guess at what is happening in other people's lives and how the narrative will unfold. Then there are books recounted from multiple perspectives, perhaps the most stunning in the genre André Brink's A Chain of Voices, in every chapter ambushing the reader into another version of reality, reminding us that every story, every history depends on the narrator.

In David Edmond and John Eidinow's (2001) wonderful account of the historic Cambridge meeting between Wittgenstein and Popper, Wittgenstein's threat to Popper with a poker is pieced together from those who were there – eminent scholars, all of whose testimony to the events is different in significant detail. Perhaps it was the emotionally charged nature of the event that brought so many disparate recollections but the authors leave us not knowing what actually happened or even who was there and who was not.

So it is with the evaluation of schools. How we judge our schools, how we describe events within them depends entirely on who tells the story. Some inspectors may lay claim to an objective truth but, as we know, there are many truths and many different ways of seeing the same event. School self-evaluation at its richest and most profound explores that dangerous territory, seeking out the anomalies and contradictions. As we see in this book, a good lesson, a good teacher, a good learning experience is not some objective entity but dependent on where you sit, what you bring to that judgement, how you frame or construct the situation. So we read accounts of two students in the same class with the same teacher – one engaged, one bored, one seeing the teacher as a source of inspiration, one pursuing her own learning path in spite of the teacher. The freedom of the Swedish school is relished by some while others struggle with the lack of structure and direction around them. In the highly structured Czech school some find their own direction while others are stifled by the lack of opportunity for individual expression.

The Learning School students too, as itinerant evaluators, bring their own histories, cultures, linguistic conventions to their observations in classrooms and in post-lesson interviews. (See pp. 15–26 for a full description of the Learning School Project.) What they see is determined by habits and ways of seeing. What they elicit in interviews is dependent on the questions they ask, their understanding of the answers and their translation of these ideas into their own linguistic register – even when speaking the same language. But their great asset is time – time to go back and verify what they have understood. Their great strength is the dialogue that takes place within the group over time, revisiting and refining their individual and joint learning. And their primary advantage is their status (or lack of it). They are themselves schools students, shadowing other school students, so they are able to get close to the real and very different experiences of life in school.

But they leave us with as many questions as answers. They never lay claim to objectivity or definitive truth. But their own accounts and the accounts of students they observe have a special authenticity because they resonate with our own experiences as students or teachers and with a rich vein of ethnographic literature.

The Learning School has, over three years of its life, constantly re-invented itself and is known within its own restricted code as LS1, LS2, LS3, for its three successive incarnations. Each new group of students, recruited from the participating schools, is able to build on what has gone before so that the Learning School is indeed a learning community with a distributed intelligence and an organisational memory. But year on year those who join have to experience for themselves the immense challenges not only of the research task but of living and working together as a team.

It is almost impossible for a book to capture the vitality and excitement of the Learning School. It is impossible for words to contain the intense frustrations and anxieties that are integral to real and powerful experiences of learning. This is such a unique experiment in school improvement, a story is so rich in all its facets, that we struggle in a book like this to find a beginning. Arundhati Roy tells us that all beginnings are contained in their endings so you might like to start with the personal accounts of students written at the end of their learning journey (Chapter 4). Or begin with the accounts from teachers as to the impact on their schools (Chapter 5). Or the impressions of people who were at presentations by the learning school students – some eminent researchers in their own right, some policy-makers and some teachers (Chapter 6). Or, if you choose to start at the chronological beginning then it is Chapter 2 which describes what the students did on their global itinerary while Chapter 3 describes the range of tools used by the Learning School group to probe beneath the surface of overt behaviour and explore the inner life of learning and motivation. Perhaps we will gather some data on how people do read this book and we will further our understanding of that much abused notion of learning styles.

Part II (Chapter 7 onwards) sets out some of the findings. To provide them all would require an encyclopaedia, so voluminous were the data collected by each successive cohort of students. So, in the editing of these chapters we are only offered glimpses into the lives of school students in six countries but these short extracts are very telling in what they reveal and in what is often concealed from teachers and parents. We learn something of the rhythm of the school day and the rhythms of learning. We see evidence of engagement and disengagement, interest and boredom, anticipation and dread, anxiety and frustration. We are offered insights into rising and diminishing confidence, growth, diminution and fluctuations in self-esteem. We begin to make connections between what teachers do and what students do but discover that the causal relations are not as reciprocal as we might assume. We read of young people living out their own lives in classrooms in which sometimes teachers and peers are a distraction from their learning. We follow them into their home and family lives and discover an equally tenuous relationships between parents and their children. Parental guidance and help are often interpreted by young people as intrusive and irritating. And we discover a corollary too. Some parents see themselves as having little influence because they apparently do nothing but their children testify to a powerful underpinning sense of support. And so it is with teachers who convey implicit messages to their students and which students read with an acute emotional intelligence.

There is so much here that reflects and reinforces studies by researchers who have penetrated the underlife of classrooms, but in these chapters it comes from first-hand accounts of young people who have not yet read those books but may now come to them with a deepened understanding. There are further insights too because this has an international dimension and reminds us how similar and how different school life is the world over. It causes us to question again what school is and what it does. It poses a whole new raft of questions about school effectiveness and the meagreness of the measures we have often brought to that line of inquiry.

It is set in the context of a growing comparative database from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the European Commission and TIMSS (the Third International Mathematics and Science Study) in which countries are ranked in terms of their impact on student learning. A comparison with the recent PISA study (OECD, 2001) is revealing. These students have covered some of the same ground as PISA, in some cases arriving at quite similar conclusions, in others being able to probe deeper beneath the statistical surface of data which, presented in raw form in the PISA tables is difficult to make sense of. Korea is a case in point. It comes out well in PISA's comparative performance rankings but accompanied by some quite baffling data. Why, for example is it one of the countries in which students say they are least in control of their own learning? Why does it do worst of all countries on cooperative learning? Why are Korean students below the international norm on interest in mathematics and reading? Why is Korea so low in its ranking (well below the international norm) on time spent on homework? Why, equally remarkably, is Japan the country with least time on homework of all OECD countries? PISA does not provide us with the answers to these enigmas but we do get much clearer insights from the students of the Learning School who also collected data on homework but went further to observe young people doing their homework, questioning them on their approach and attitude both in the home and classroom context (see Chapter 19 for PISA data on homework).

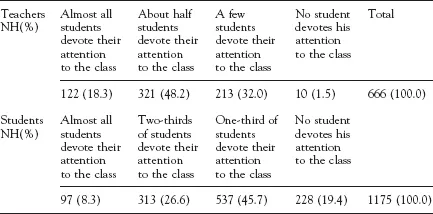

While the Learning School only visited one school in each country (including Korea) we begin to see things through a different lens, classrooms refracted from the inside, in which the quality of learning is put to a stern test. No claim is made that these schools constitute a representative sample, but nonetheless each does reflect its surrounding culture. In all cases the classroom is but one source of learning and the differences in cultural settings from Japan to Sweden are arresting. In his own testimony, given at the International Congress in Copenhagen, a student from Korea described how, for the first time in his ten years of schooling, he had begun to ask questions, to think, to discuss, to find new frames of reference. By coincidence and happy accident, on the same day a Korean researcher presented a paper on the Korean educational system. Questioning its high standing in the recent PISA ‘league table’, he argued that it was not the school that added the value to student scores but the extra tuition that students got outside school in a society obsessed with high achievement. He finds that students are often too tired from their extra-curricular efforts to pay attention in class and he produces a statistic which has such clear resonance with the methodology and findings of the Learning School students that it is worth reproducing here. It asks teachers and students the same question. What proportion of students during a typical lesson are paying attention to what is being taught? (see Table 1.1). Teachers and students tend to agree that this is clearly a problematic concern but the differences in their respective judgements parallel closely the findings that appear in this book.

These Korean students, like many identified in the Learning School studies, are highly efficient motivated learners and hence do well in exams, planning and studying and with well developed strategic approaches to achievement but they appear to meet only two of Zimmerman's three criteria of self-regulation: ‘Self-regulation refers to the degree that individuals are meta-cognitively, motivationally, and behaviourally active participants in their own learning’ (Zimmerman et al., 1994).

Table 1.1 The degree of student's attention in classes

Source: Yi, Jong-Tae et al. (2000, p. 66)

As the LS3 researchers found, the meta-cognitive aspect was least well developed and often even virtually absent among secondary school students. Many students, as Chapter 18 tells us, were weak in self-evaluation, too busy learning to consider how they were learning. This was not peculiar to Asian-Pacific countries but true in all schools, even those where teachers expressed a concern for learning how to learn.

While there is, throughout the chapters of this book, a consistently high level of praise for good teachers and good teaching, students are less fulsome when it comes to the quality, pace or exuberance of their learning. In Chapter 4 Learning School students from all participating countries testify to failures of a regime which did not move them beyond their intellectual comfort zones or extend their horizons. All participants write about the skills and understandings that they never acquired in school and some describe in detail the skills they gained working as a team and the accountability that went with it: social, moral and intellectual accountability – to one another, to host families, to schools and to the project on which they had, with some trepidation, embarked. These are some of the skills described:

• challenging your own values and assumptions;

• learning to see things from different perspectives;

• working as a member of a team;

• exercising leadership;

• learning to compromise;

• observing with discrimination;

• working to deadlines;

• taking difficult decisions;

• learning to deal with conflict;

• making presentations to large, and critical, audiences;

• exercising initiative;

• writing for different audiences;

• increasing self-knowledge.

We cannot help being struck by the contrast between how these young people now talk about their learning and the comments made by those whom they interviewed. For the school students, learning is typically described in terms of volumes of notes taken, efficiency in preparation for exams, success in tests. The student researchers, on the other hand, describe months of struggling to get to grips with what motivation and learning really mean and they describe how long it took to come to a new and critical understand of their own learning.

Before I joined Learning School, motivation was something I never thought of and suddenly I had to find out what made other students want to learn before I knew what made me learn. I spent some time reflecting on myself and today I can say that I came up with things I never thought influenced me at all because I always thought I did things for myself and not for any other reason. Now I am looking forward to going back to school and seeing how much I will reflect on myself in the classroom as well as the teachers and my peers. I hope that now I have enough knowledge about motivation and I am able to motivate myself in all subjects.

(Karolina)

It has been said that fish were the last to discover water and that, sadly, school students are often the last to discover learning. So, in examining data on students’ accounts of learning we have always to return to this question of definition and awareness. One of the tantalising paradoxes is that the most satisfied students may be the least aware and least negative in their appraisal while those who have learned most about the nature of their learning may be the most critical. We are still in the foothills of our understanding of learning says Harvard's David Perkins and perhaps the more we ascend, the less sure we are of our foothold. In Guy Claxton's terms – a developing confidence in uncertainty:

Learning starts from the joint acknowledgement of inadequacy and ignorance … There is no other place for learning to start. An effective learner, or learning culture, is one that is not afraid to admit this perception, and also possesses some confidence in its ability to grow in understanding and expertise, so that perplexity is transformed into mastery.

(Claxton, 2000)

The following extract from Colin Bragg's account captures something of the nature of learning, ‘a winding and sometimes misty path’. Not at all like the clear objective, the plan and the smooth linear path to its fulfilment.

To think that in at the very beginning of this project we as a group were looking through textbooks in an attempt to understand the word ‘Motivation’ and now a year down the line a report on the subject of motivation in all of the schools we visited exists. Somehow in amongst the arguments and lengthy debates our determined co-ordinators led us on a winding path, that even they will admit became a little misty, in achieving our objective.

(Colin)

How it came about

The background to and origins of the Learning School, an international year of living and learning together for smal...