- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Architecture, Actor and Audience

About this book

Understanding the theatre space on both the practical and theoretical level is becoming increasingly important to people working in drama, in whatever capacity. Theatre architecture is one of the most vital ingredients of the theatrical experience and one of the least discussed or understood.

In Architecture, Actor and Audience Mackintosh explores the contribution the design of a theatre can make to the theatrical experience, and examines the failings of many modern theatres which despite vigorous defence from the architectural establishment remain unpopular with both audiences and theatre people. A fascinating and provocative book.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Subtopic

Performing ArtsPart I: History

Chapter 1: Continuity of character?

Most guides to theatre architecture take the reader back to the Greeks or even to the forest clearing, if the author seeks to suggest that theatre in the round is the most ‘natural’ of theatre forms. But if we are to understand the continuing evolution of western theatre, then not only is there no need to go back beyond the theatre of Shakespeare, but to start with ancient theatre may be confusing for all but the specialist. Of course, the ancient theatre, the medieval theatre and the oriental theatre are relevant, but these forms of theatre did not shape our theatre directly. Rather have theatre people in the last couple of hundred years become enthusiastic for the introduction of this foreign style or for the revival of that past practice. Often the motives and prejudices of those who advocate foreign or archaic forms of theatre are of greater interest than the forms themselves.

Shakespeare and his contemporaries in Europe and, most significantly, in Italy are the primary influences on western theatre. They are our theatrical forebears. Our present theatre has evolved directly and continuously from theirs.

However, so incomplete has our knowledge of Shakespeare’s theatre been over the last two or three hundred years that until recently all ‘reconstructions’ were conjectural and subconsciously clothed in the fashionable style of the day. The innovatory bare stages and ‘contemporary’ Elizabethan costume of William Poel at the end of the ninteenth century, ideas taken up by Granville Barker in London, Nugent Monck in Norwich and Folger in Washington, appear today curiously dated. Nevertheless each generation of the last hundred years has found some architectural inspiration in Elizabethan theatre. Within a single generation different groups have provided different interpretations. Compare, for example, the thrust stage conceived by Tyrone Guthrie at Stratford, Ontario (1953 and 1957), which is enfolded through more than 180 degrees by the audience, and the open-air ‘Globe Theatres’ of the American west, where fan-shaped auditoriums confront Elizabethan ‘tiring houses’ with no encirclement but a lot of period architectural detail behind the acting area, such as might have been conceived by a movie art director of the 1930s. Yet both satisfy audiences and provide for them a sense of Shakespearian occasion.

The cauldron of theatre architectural history bubbles with many unusual ingredients. It is equally tedious to extract one element and examine it to the exclusion of the others as it is to examine all the influences as if all were equally important. The purpose in devoting the first three chapters of this book to theatre history has been to take a rapid walk down the main street of British and American theatre architecture over 400 years and see whether its development is marked by sea changes which transform the nature of theatre or whether there exists a continuity in the character of the playhouse. Inevitably one starts with Shakespeare’s ‘unworthy scaffold’ or ‘the great Globe itself’, looked at not as an end in itself but as an ancestor to a family of theatres which have recurring family characteristics.

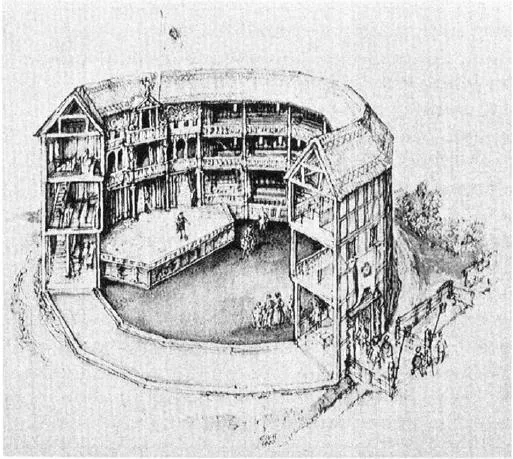

There are a number of theories on the origins of those multi-tiered open- air public theatres of Elizabethan London which are so familiar from this or that artist’s impression. The evidence is incomplete because the primary evidence will always be confined to foundations rather than structure and the secondary evidence to precious few reports or illustrations. But we do know that the first such open-air theatre, The Theatre, was built in 1576 in Shoreditch, north London, by James Burbage, and that the last ones were built only thirty-eight years later in 1614. Every new archaeological discovery refines our knowledge of the high noon of these theatres that spans the openings of the first of the Bankside theatres, the recently rediscovered Rose of 1587, and of the last, the second Globe of 1614. But whatever the archaeologists and other scholars have still to tell us there is no doubt they had a common ancestry and a common purpose.

Some see the latter as having been the need for pragmatic managements to increase the size of their companies’ summer audience which hitherto had been accommodated in innyards. Carpenters such as Peter Street, or engineers as we would call them today, provided for managers such as Henslowe as tall a structure as timber technology would easily allow. The management would decide how broad and how long these structures were to be from their knowledge of how far an actor could project. On occasions the size of the site was a factor. No time for architecture: ‘get it up and pack them in’ is the prosaic picture proposed by some pundits of how and why it was done.

Other scholars are more philosophical, and none more so than Frances Yates in Theatre of the World (London, 1969). She sees the Globe not just as an ‘original adaptation of ancient theatre in the tradition of the renaissance revival of Vitruvius’, but also as a theatre of magic, an actor’s microcosm in the image of the cosmic macrocosm which gave real meaning to Shakespeare’s words ‘all the world’s a stage’. The neo-Platonic theory revived by renaissance philosophers was that there were spatial harmonies which were as measurable and as significant as musical harmonies. A theatre which was to work successfully for actor and audience had to have proportions specified by the ancients. These proportions were simple to calculate and could be easily followed by any craftsman who understood a few simple techniques of ‘setting out’ involving a rope divided by 12 knots into 13 sections (by which a 3,4,5 triangle with a right angle, a 4,4,4 equilateral triangle or a 5,4,4 isosceles triangle, which is a seventh part of a circle, can be produced) and a measuring system made up of ‘rods’ and their subdivisions. A rod is five and a half yards or 16 feet 6 inches (5m). The whole system was easier to apply than the modern method of starting at one end of the plot and marking out the measures from a scaled plan. Thus the philosophical mystery also provided a pragmatic method.

Both views are probably correct despite being often overstated. Immense scholarship is still needed to unravel precisely what Shakespeare’s theatre was like, because until the Rose and the Globe were excavated in 1989 there had been no first-hand evidence and only the one source of reliable secondary evidence, ‘the de Witt drawing’, which is in fact a copy by Arend van Buchel of Utrecht of what a traveller friend had sketched on a trip to London. De Witt added a commentary, concluding with the information that the Swan which he had sketched was ‘supported by wooden columns, painted in such excellent imitation of marble that it might deceive even the most prying…its form seems to approach that of a Roman structure’. Add original sources to today’s archaeology and it appears that the open-air Elizabethan theatres had six fundamental features.

These were first that they were conventional constructions by craftsmen rather than innovative designs by architects. Second, their scale corresponded with the ‘found spaces’ previously used as theatres such as courtyards of the inns of London and of principal towns to which the actors toured. Third, their form was recognisably classical. Fourth, the finish of the theatres was itself an illusion, i.e. the marble was painted, not real. Fifth, they packed as many people as possible in a given site or ground plan. Sixth, the focus that is all-important in a theatre was given by a pure geometry which was not only a technical tool but also had then and still has a mystical significance which cannot easily be explained.

No single feature would seem today to be unusual except possibly the sixth. That these theatres had all the other features might be expected from intelligent business-like managements commissioning confident craftsmen. What is truly remarkable is that all these elements were in balance one with another. The Elizabethan theatre managements and their craftsmen got it right and the buildings were not only huge public successes, but also helped inspire the greatest flowering of dramatic literature.

The need for further research and for conjectural reconstruction is no longer in question. Scholars are being constantly surprised at fresh discoveries, for example in late 1989 that the second Globe may have been fourteen-sided. This may not fit the geometrical rationale of Frances Yates but does relate to the thirteen sections of the medieval measuring rope (the 5,4,4 triangle which is one-seventh of a circle) and is, incidentally, the geometric basis of the Royal Exchange, Manchester, built in 1976 where the internal diameter of the fourteen-sided space relates to the outer perimeter through the square root of 2, the key to the ad quadratum geometry of so many successful theatre spaces.

But although we are still some way from unravelling the more esoteric mysteries of Elizabethan theatre architecture, it is clearer now that these essentially simple structures were highly efficient at maximising the box office. Their builders succeeded in getting as many people as close as possible to the actor without jeopardising the actors’ primary task of communicating with every spectator, however distant.

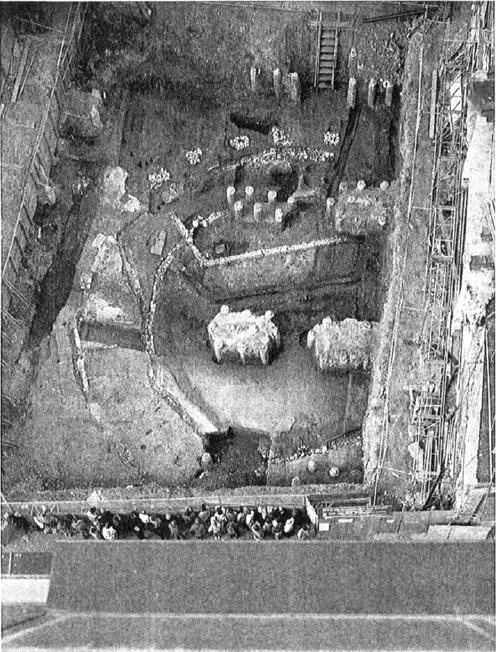

The Rose excavation in summer 1989 illustrated perfectly the practicalities of pragmatic Elizabethan theatre architecture. What was immediately apparent was that there were two stages and two lines to the inner wall of the encircling tiers. The first theatre of 1587 was a regular twelve-sided doughnut with the central area occupied by the standing groundlings around three sides of a stage. This projected far out into the yard but not quite to the middle. But in 1592, only five years after it had opened, Philip Henslowe enlarged the theatre. The stage was pushed back 8 feet, and the encircling tiers extended on each side of the stage with the result that the form became far from regular.

In addition, a well-documented altercation with the authorities meant that Henslowe had at the same time to realign the audience end of the structure to remove the foundations which were interrupting the flow of the open drainage ditch to the south. C.Walter Hodges in a paper entitled The Rose: A Reconstruction in Progress given to the Society for Theatre Research at the Art Workers’ Guild on 16 October 1990 suggested that the changes to the stage were occasioned by the real need for increased room for properties and dressing which had been badly provided for in the original harmoniously shaped Rose. However, Professor Andrew Gurr suggests the consequential 25 per cent increase in capacity would have had to have been sustained for over twenty-five years for Henslowe to recover his expenses in remodelling the Rose—not the last time that the cost of theatrical improvements has exceeded estimates. The second enlarged Rose may have staged the first performance of Henry VI by the young William Shakespeare but it seems to have lost the purity of the original form and presented a lopsided appearance. Was the second as good a theatre as the first?

The second enlarged Rose had a life of less than ten years. In 1600 Philip Henslowe replaced the Rose with the Fortune, which we know from the original building contract to have had the most regular form possible: a square. At the Fortune the demands of the box office and backstage needs were satisfied within a totally harmonious form. The regular square of the Fortune is less attractive to us than the polygonal Rose, Swan and Globes but the Fortune flourished for over forty years until all the theatres were closed by the Puritans.

The tension between the demands for spatial harmony and for increased box office are complex and universal. In 1989, irrespective of whether one focused on the footprint of the first or second Rose, what was marvellously simple about the exposed foundations was the sense of scale it gave to the visitor. This was the theatre of Marlowe’s ‘mighty line’. Here, in the first Rose, Alleyn played Tamburlaine. Yet that summer, standing at the side looking down on the excavation, exactly where one would have been in 1587 in the front row of the middle tier slightly to one side and facing the stage, one felt one could reach out and touch the actor. The original stage line was less than 30 feet (9.1m) away and the internal yard about 49 feet 6 inches (14.8m)—3 rods in old English measure—wide. How many did the Rose hold? Some commentators, including those as distinguished as Anthony Burgess, were confused. Writing in the New York Times of 11 June 1989 he concluded: ‘It now appears that only a couple of hundred could get into the Rose. This seems commensurate with the size of the area the excavators have exposed, but one wonders how, with such a limitation, the Rose made any money.’ This is quite wrong. Anthony Burgess miscalculated because he thought that density was a constant through the ages. A different attitude to density is needed. Thomas Middleton (1570–1672) described ‘the groundlings’, standing in the central area surrounded by the rising tiers of boxes, most vividly in The Roaring Girl which played at the Fortune in 1611:

Within one square a thousand heads are laid,

So close that of heads the room seems made;

As many faces there, filled with blithe looks,

Show like the promising titles of new books

Writ merrily, the readers being their own eyes,

Which seem to move and to give plaudites;

The very floor, as t’were, waves to and fro,

And, like a floating island, seems to move,

Upon a sea bound in with shores above.

The first Rose was two-thirds the size of the later and larger houses, such as the Globe. There is enough secondary evidence that the Swan and the Globe held 3,000. Ergo, the first Rose held 2,000, the second probably 2, 500, in a space which today, for a number of reasons, would hold not more than 400 or 500. First, the twentieth-century body is larger in height and width than the average Elizabethan body. Second, few today would stand for an entire show as all the audience did in the central yard of an Elizabethan theatre, although a modern pop concert audience stands and will sway in the way Middleton suggested. Third, the seated audience today demands comfort as well as space for its longer legs. Fourth, the fire officer of the twentieth century demands gangways, aisles, staircases and a limit on capacity at each level so that the audience is controllable in an emergency. All these are measurable, and the sum effect is that the Elizabethan theatre would have held three or four times as many people as a modern theatre of the same size.

1 (left) The rose revealed in a photograph taken by the archaeological unit of the museum of London in May 1989 before the controversial office block was built above. Two-thirds of the theatre is revealed and the lines of the two stages, of 1587 and 1592, are clear, as arethe piles for a 1957 office block which miraculously missed the then undiscovered foundations.

2 (above) Reconstruction by C.Walter Hodges of the original Rose of 1587 into which 2,000 people must have been crammed.

The intimate scale of the excavated Rose was for many a surprise. It appeared to be more like the Cottesloe or the Criterion in London or a West 42nd Street off-Broadway theatre in New York than to possess the size which a capacity of 2,000 conjures in the mind. This will be but the first of assertions that seating capacity is an unreliable measure for the size of a theatre. The Rose excavation provides early evidence that great theatres which nurture creative drama are usually very small.

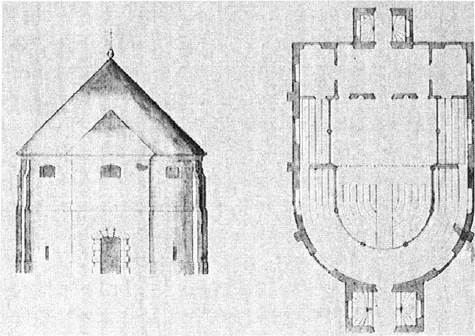

The Elizabethan public theatres were closed in 1642 as a result of the rise of Puritanism. Theatre activity in the eighteen years of the Common- wealth which followed was restricted to private houses, and the public theatres that reopened on the restoration of the monarchy in 1660 appeared to be very different. However, many textbooks have over emphasised the difference between the post-Restoration indoor theatres, created by Davenant at Lincoln’s Inn Fields (1661) and at Dorset Garden (1671) and by Killigrew at Drury Lane (1662), and the pre-Commonwealth public theatres of Bankside. By stressing that Restoration theatres had proscenium arches while the earlier ones apparently did not, many historians have given too little weight to the continuity of theatre architecture. This continuity becomes apparent when comparison is made between the relatively well-documented Restoration theatres and not only the little we know of London’s ‘winter’ or private theatres, such as the indoor Blackfriars as used by Richard Burbage and hence Shakespeare’s company, but also the great deal we know about an indoor theatre designed by Inigo Jones in the mid-1630s, probably as a reconstruction of the 1616 Phoenix in Drury Lane, for which plans survive.

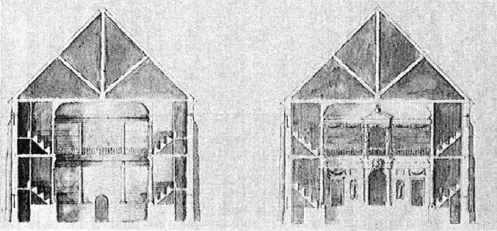

The Inigo Jones design shows an adaptable theatre capable of being used either as a single-space theatre with a platform surrounded by audience on three sides, not unlike the pre-Commonwealth public theatres, or as an end- stage scenic theatre, not unlike the post-Restoration theatres. The possibility of placing within a pre-Commonwealth indoor private theatre the sort of scenic spectacle which hitherto had been thought to be confined to the Royal Masking houses of Charles I and not to have made its appearance in the public theatres until 1660 was first proposed by this author in Tabs Vol. 31 No. 3, September 1973 and later endorsed by Professor John Orrell in Shakespeare Survey 30. Two scene designs exist which would fit the Cockpit in court perfectly. One is a drawing by Inigo Jones himself inscribed ‘For ye Cokpit to my lo Chambralin, 1639’ and the other a stage plan for The Siege of Rhodes in the Lansdowne Collection at the British Museum which was designed by John Webb in 1656 for William Davenant and which after the Restoration in 1660 was revived at the aforesaid Phoenix (or Cockpit).

This is evidence of a continuity of character in theatre architecture which connects the Restoration back to the time of Shakespeare. It is also possible to demonstrate that this continuity of character stretched on even further to the end of the eighteenth century through the nineteenth century to the present day. Evidence includes the building today of theatres of a scale and capability such as the Tricycle Theatre, Kilburn, London (1980, and rebuilt after fire 1989), similar to the still extant Georgian Theatre, Richmond, Yorkshire (1788). Such mainstream playhouses hold between 150 and 450 at modern densities, have an acting area at one end which is between 16 feet 6 inches (15m) and 33 feet wide (10.1m), dimensions which are, precisely and respectively, one and two rods. They generally have galleries either at one end or on three sides of a central space. The gallery facing the main acting area is generally between 16 feet 6 inches (5m) and 33 feet (10. 1m) from the edge of the stage. There is usually either a proscenium arch or a point at which the architectural treatment of the side wall changes. This break is at right angles to the longitudinal axis. The existence of the proscenium, or break in the architecture, did not necessarily mean that the audience’s territory stopped at this point: in many such theatres, old and new, the audience sat at the sides of the acting area upstage of any proscenium arch if there was one and, on some occasions, behind the actor.

3 and 4 The drawings by Inigo Jones now in Worcester College, Oxford, which may be for a rebuilding in 1636 of the Phoenix, Drury Lane first opened in 1617. Whether executed or not they are the oldest extant drawings of any theatre in the English-speaking world. That this may have been an adaptable theatre is suggested by the wall either side of the front of the stage which is unnecessary for any structural purpose. It is possible that on occasions the audience was banished from the sides and the rear of the platform stage which then served as a proscenium stage. The latter is precisely sized for Davenant’s The Siege of Rhodes, ground plans of which are in the British Museum. The drawing by Inigo Jones, dated 1639, of a perspective setting behind a round arched proscenium would also fit precisely between the walls each side of the front of the stage.

Of such a basic form were the indoor theatres of Elizabethan London, the aforementioned Inigo Jones theatre and the theatres at Lincoln’s Inn Fields which flourished intermittently between 1661 and 1733. Most theatres of that period both here and in France were no bigger than a royal tennis court—not surprisingly since many were conversions of royal tennis courts, which means that the internal dimensions of the whole str...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Architecture, Actor and Audience

- Theatre Concepts: Edited by John Russell Brown: University of Michigan

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Illustrations

- Introduction

- Part I: History

- Part II: Today

- Part III: Tomorrow

- Select bibliography

- Apologia and acknowledgements

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Architecture, Actor and Audience by Iain Mackintosh in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Performing Arts. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.