This is a test

- 324 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

City and Country in the Ancient World

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The ancient Greco-Roman world was a world of citie, in a distinctive sense of communities in which countryside was dominated by urban centre.

This volume of papers written by influential archaeologists and historians seeks to bring together the two disciplines in exploring the city-country relationship.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access City and Country in the Ancient World by John Rich in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Historia & Historia antigua. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Archaeology and the study of the Greek city

A.M.Snodgrass

For well over a hundred years, people studied the Greek city as an entity without making more than negligible use of archaeological evidence. As late as 1969, in the translated second edition of Victor Ehrenberg’s Der griechische Staat,1 the reader has to search very hard indeed to find even a veiled recourse to archaeology. The historians of the polis saw themselves as dealing essentially with an abstraction; they avoided tawdry physical detail, much as they tended to eschew the whole diachronic approach; and both exclusions rendered archaeology superfluous. The archaeologists showed little sign of minding this: they carried on studying their temples, statues and pots, innocent not of all historical considerations—from the 1930s to the 1950s was, after all, the golden age of the ‘political’ interpretation of pottery-distributions—but certainly innocent of any concern with historical entities like the city-state.

Today, all that appears to have changed. Some books on aspects of the polis are being written by historians who make constant reference to archaeological findings; others are even written by archaeologists. What factors have brought about such a change? An important contributory factor has been the minor wave of new archaeological discoveries, relating especially to the era of the rise of the polis. But what generated this wave? The answer lies partially in an initiative on the part of historians: which brings us to a second and more fundamental factor. There has been a change of attitude, on the part of historians and archaeologists alike. The former are now no longer content to give, like Aristotle in the Politics, a more or less theoretical reconstruction of the advent of the polis, set in some indefinite early period: they feel an obligation to offer some kind of account of the date, causation and means whereby the entity that they are concerned with came into being. To do so, they must venture back into periods where the written sources on their own are manifestly inadequate. So they have called in the archaeologists, who in turn have been surprised to find that they are already sitting on a substantial body of existing evidence that is relevant to the problem, as well as responding to the call for new excavation to fill in the blank areas on the map of early Greece. The fact that so much of the evidence was long since available, however, must mean that it is this change of attitude that has been the decisive factor. In a nutshell, explanation has taken over from analysis and description as the prime aim, in both disciplines. I hope that, to most readers, these will be welcome developments.

These considerations all relate to one large area of the study of the polis, that of its origins and rise: this is indeed a topic where archaeology plays a major role, which is why it will feature prominently in this paper. But there is a second such topic in polis studies, which has likewise benefited from new archaeological work, and from a parallel change of attitude. It is the whole question of the physical basis on which the Greek city rested: the territorial sector and the rural economy. Here, the seeds of the change of attitude may be detected very much longer ago; but they were sown outside the boundaries of Classical scholarship (I have the name of Max Weber especially in mind) and, perhaps for that reason, they took an extraordinarily long time to germinate; indeed, but for the stubborn advocacy of Moses Finley, I rather doubt whether even now they would have burgeoned into the flourishing growth which they present today in ancient historical studies. In the archaeological field, they fell on even stonier ground, and I believe that the change of direction in archaeological studies has other causes. In passing, both sides alike should pay tribute to a third group, the epigraphists: with many of the relevant topics, from topography in general to the constitutional arrangements as they affected territories, to territorial boundaries, to agricultural slavery, it was they who were often first in the field.

The opening up of this second field of enquiry (or so I am suggesting) has come about through a fortunate coincidence of interests between recent historical and archaeological research. The historians, as soon as they became conscious of the need to examine the agricultural basis of the city, found that the evidence from the ancient written sources was seriously defective, and began to look round for alternative kinds of documentation. The archaeologists, having for so long followed the historians in their concentration on the urban sector of polis life, were in no position to assist. But help was at hand, and from an unexpected source. Archaeological colleagues in northern America were beginning to supplement, or even replace, excavation as the traditional medium of fieldwork with the new technique of area survey. Here was a technique which, unlike excavation, was designed to generate information on a regional scale, and with a rural bias. Methods which had been applied to the indigenous cultures of North America, by people who often had little interest in urbanised cultures and none at all in the Classical city, were found to be eminently applicable, first to pre-Roman or Etruscan Italy, then to the period of Roman rule in Italy and beyond, and finally to the world of the Greek city. A survey could provide a picture of the pattern of settlement over the whole territory of a medium-sized polis, or over parts of those of several poleis, and would also have an application in the more extended landscape of the average ethnos— exactly what the historians needed.

As a result of all these developments the study of the polis, at least when conducted at the generalised level, has become more and more deeply involved with the use of archaeological evidence. If we return to our first topic, that of the origins and growth of the city, we may begin our search for applications, actual or potential, of such evidence. In his opening chapter, Ehrenberg (1969) divided his treatment of this subject into five sub-headings: ‘Land and Sea’, ‘Tribe and Town’, ‘The Gods’, ‘Nobles and non-nobles’, and ‘Forms of State’. Except for the last category, where the enquiry is essentially historical in nature and is conducted through backward projections from later documentation, I believe that archaeology can contribute in each of these spheres. It can offer not only the classes of evidence, referred to above, which are specific to the case of the Greek city, but also a body of recent work that is directed towards a general theory of state formation, based on anthropological research but later given an archaeological application.1 Although such work has been mainly applied to non-historical cultures, some of its findings are relevant to the case of ancient Greece: notably, the idea of an ‘Early State Module’ that is essentially small in scale,2 though hardly as small as the typical Greek polis. Indeed, a case could be made for treating even the polis, at its stage of formation, as a non-historical instance, since it is almost entirely lacking in contemporary documentation. This is generally true of early states: the discovery of writing seldom precedes state-formation by a long enough interval to generate coherent documents by the time of the political change.

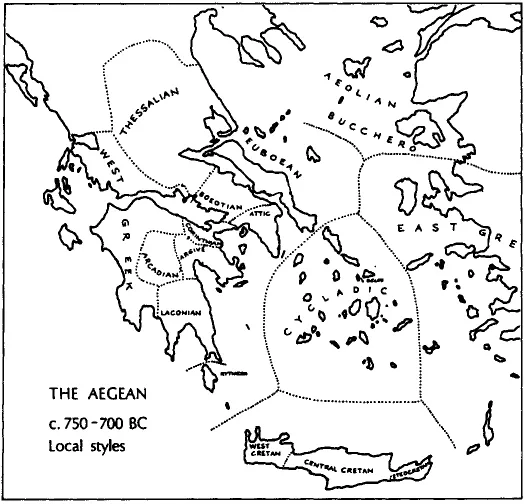

Figure 1a: Extent of the regional Late Geometric pottery styles

Figure 1b: Extent of the polis system (shaded)

A good starting-point for the discussion is the primary importance that Aristotle attached to ‘community of place’—perhaps the earliest clear acknowledgment that the abstraction of the polis had an inseparable physical embodiment. Community of place incorporates both the astu, the central place, whose function was transformed when the state came into being, and the territory, which henceforth consisted of the sum of the landholdings of all members of the community. These are changes which can be expected to have manifestations in the archaeological record. What we must guard against is any expectation that these manifestations will be uniform in every case. The physical impact of polis-formation would vary according to the different prior conditions in the region where the particular polis arose. We know little enough about these prior conditions in any part of the Greek world, but what we do know can at least be expressed in archaeological terms. Thus there is the interesting fact, whose significance was spotted by Ehrenberg and has recently been enlarged upon by Nicolas Coldstream,1 that the area of the Greek world where the Geometric style in pottery had reached its most advanced development (fig. 1a), and the area where the polis was to prevail (fig. 1b), roughly coincide. The priority of the archaeological phenomenon will stand unless we push back the rise of the polis to an improbably early date, nearer 900 than 800 BC. How much weight we attach to this coincidence will depend on our assessment of the importance of Geometric pottery: but we may at least recall the arguments advanced by Martin Robertson for thinking that, at this early period, painted pottery in general held a primacy among the visual arts which it never recovered later.2 It may be that artistic sophistication was a foretaste of political progressiveness.

How then, precisely, might political transformation be reflected in the physical aspect of city or territory? We may begin with the astu itself, and assume that the circumstances were not those relatively simple ones where a physical synoikismos took place, with part of the population moving to a newly established urban nucleus, nor those even simpler ones of the colonisation of a new locality. In other words, we assume that there was a pre-existing settlement, whose status was now transformed through its becoming the centre of a polis. How will this show? It is possible that some kind of concentration will have occurred at the site, with new functions and perhaps new inhabitants being transferred to it, and that this will show itself in a nucleation of buildings—possible, but by no means to be counted on. That a ‘nucleus’ could continue to take the form of a cluster of separate villages, long after the transition to polis status, is proved not only by Thucydides’ well-known reference to fifth-century Sparta (1.10.1), but by the findings of survey archaeology elsewhere in the Greek homeland. That an agora would now be a necessary feature is no guarantee of its archaeological traceability. An acropolis would in many cases have been in existence long since, and archaeology has contributed here by showing how often it was the very same that had once served as a Mycenaean citadel. Administrative buildings, as is shown by the example of several cities, could at first be dispensed with. Sanctuaries are another matter, but they will be treated presently under the heading of religion. What we are looking for above all are the physical traces of communal activity, in the service of the polity as a whole.

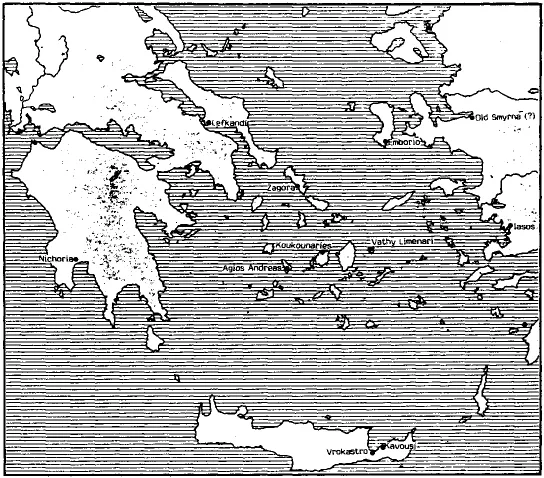

Figure 2: Fortified settlements of the ninth and eighth centuries BC in the Aegean

Such traces have often been sought in the form of fortification. Here we must be more specific: the fortification must have clearly been designed to surround the whole inhabited nucleus, and not just a citadel; and that nucleus must be of an adequate size to represent a plausible astu for the territory and population in question, rather than being merely an isolated local stronghold. The second criterion is the one that invites most debate. We have, for example, a whole series of excavated sites in the Cyclades and other Aegean islands, where a fortification wall surrounds a nucleated settlement: the earliest of these begin in the ninth century BC, if not the tenth (fig. 2). Perhaps the largest and most impressive of them is Zagora on Andros,1 which may serve as an exemplar. It has a protecting wall (among the earliest dated structures on the site), areas of housing that show clear signs of planning, a probable contemporary temple, and plenty of open space for the siting of a hypothetical agora. Was Zagora then the centre of an early polis embracing the island of Andros? Given the low population figures estimated for Greece as a whole, and the islands in particular, in the earlier Iron Age, it is not impossible that the size of Zagora, at any rate, was commensurate with that function. But if this was an early experiment, it was a short-lived one for Zagora, like so many of this group of fortified island sites, was suddenly and permanently abandoned around 700 BC. Many of the other sites in this group fail to match up to Zagora in one or more respects, principally those of size and of the location of the fortification. Thus, Emborio on Chios2 was a sizeable village, but its fortified area was confined to a narrow hilltop with only one structure of recognisable domestic function within, plausibly identified as the chieftain’s hall; much the same could be said of Koukounaries on Paros,3 where the fortified area is also a small hilltop citadel, while other nucleated sites in its vicinity are relatively small; Agios Andreas on Siphnos,4 and Kavousi5 and Vrokastro6 in eastern Crete, look more like tactically sited hilltop refuge sites than the centres of populated territories; Vathy Limenari is an almost inaccessible fortified headland on a small islet (Donoussa), and would be much more reasonably interpreted as a pirate stronghold than as an abortive polis-venture;7 and so on. The mere fact that these fortifications are mainly confined to island sites, at a time when mainland and offshore-island settlements (even those concentrated in the same epoch,like Lefkandi in Euboea8 and Nichoria in Messenia1) were unfortified, suggests that some special geographical factor, rather than a ubiquitous political change, is responsible for the walls. The long delay in building city-walls round even the most famous mainland poleis, or even, as at Sparta, their permanent absence, is a matter of record.

Instead, I think that we should concentrate our gaze on the other almost invariable feature of these fortified island sites: their lasting abandonment, usually in the years around 700 BC. It is, I think, this negative feature which gives the strongest hint of political change. What concerted process, if not state-formation, would lead to the roughly simultaneous desertion of a range of sites which for the previous century or two had been not merely occupied, but in some instances places of real local prominence (Zagora, Emborio and on the off-shore island of Euboea, Lefkandi)? Was it not that their siting, and the original purposes that had prompted it, became suddenly obsolete with the advent of a new system? That their inward-looking, security-conscious orientation formed no part of a wider community which itself promised security through communal action? If such proves to be the case, then archaeology, virtually unaided, has provided the first secure indication of the date and nature of the earliest historical state-formation in the islands of the Aegean.

By that date, the colonising process had already begun to testify to the advent of the polis in rather dif...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Introduction

- 1 Archaeology and the study of the Greek city

- 2 The early polis as city and state Ian Morris

- 3 Modelling settlement structures in Ancient Greece: new approaches to the polis

- 4 Surveys, cities and synoecism

- 5 Pride and prejudice, sense and subsistence: exchange and society in the Greek city

- 6 Settlement, city and elite in Samnium and Lycia

- 7 Roman towns and their territories: an archaeological perspective

- 8 Towns and territories in southern Etruria

- 9 City, territory and taxation

- 10 Elites and trade in the Roman town

- 11 Spatial organisation and social change in Roman towns

- List of Contributors