Power and Privilege

The most prominent theme running through the initial contact between the European invaders and the indigenous people of the islands is violence. It is difficult to envision any other way to look at what happened in those lands between 1492 and the time when one could reasonably say the era of European invasion and conquest ended, about 1550. In the beginning, the violence was the result of the wars of invasion, which lasted for more than 20 years. At the end of that period, the native people were exhausted from trying to resist the demands of the invaders. The men were killed, captured, imprisoned, and forced into slave labor by the Europeans. The women were taken from their homes, raped, and forced into slavery of all sorts, including domestic service. The youngest children also were forced into domestic service, and the culture of indigenous village life ended.

As slaves, the local population was overworked, underfed, and infected with new diseases. The illnesses went untreated and the locals began to die. The size of the indigenous population of the Caribbean at the start of this chaotic process is difficult to ascertain. The point at which that number was reduced to zero also cannot be precisely known. Nor is it certain how anyone survived the violent invasion period, but by the twentieth century, when descendants of the original inhabitants were found on some of the islands, their culture was radically different from what was described in the late fifteenth century.

At the root of this cultural destruction lay Europeans’ profound disrespect for the indigenous cultures they encountered. They expressed this disrespect in the forms of dominance they exercised, which were grounded in a robust ethnocentrism that depreciated and dehumanized people they considered uncivilized and whom they had militarily defeated. This ethnocentrism is best understood as racism.

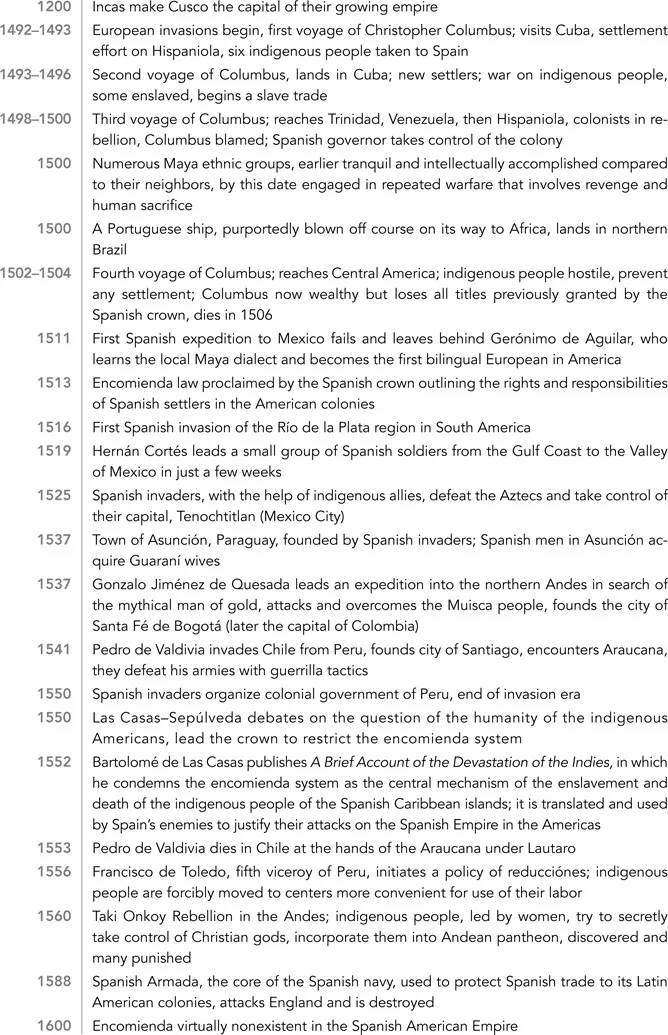

Map 1 European Invasion Routes, Sixteenth Century. Brown, Johnathan C.; Latin America: A Social History of the Colonial Period, p. 89.

It was not that the Spaniards regarded all their enemies with disrespect. In fact, they held the Muslims, who had lived in Spain and contributed to the formation of Spanish culture for 700 years, in great esteem. The Spaniards so respected Muslim culture that they adapted many of its elements and viewed them proudly as Spanish. Likewise, despite the propaganda campaign against Jews in Catholic Spain during the era of Roman Catholic reformism and deep insecurity within the Church, Jews contributed positively to Spanish culture at many levels of society. Both Muslims and Jews were seen as enemies, yet rather than being enslaved or annihilated, they were only expelled from the Roman Catholic monarchy. The people of the Caribbean islands, however, were a different story.

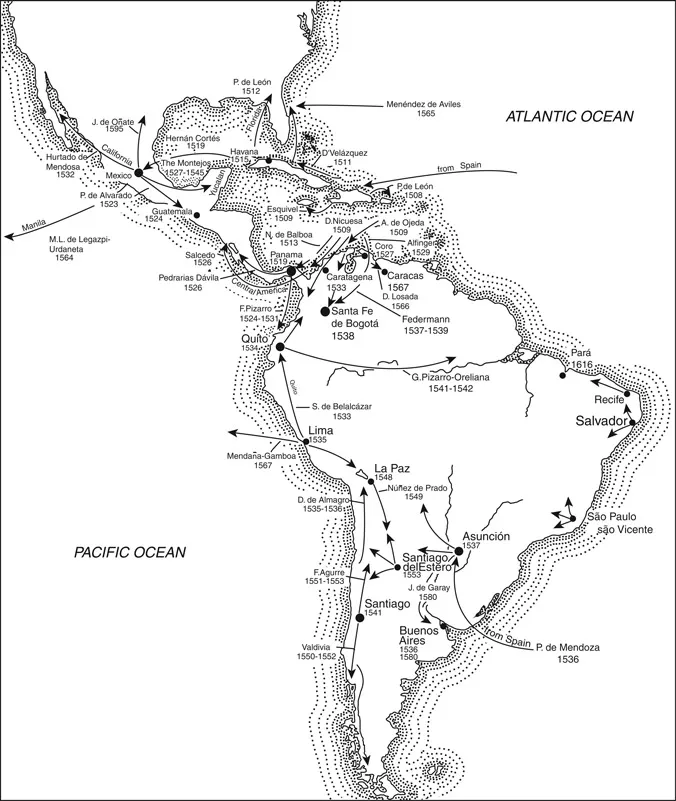

Figure 1.1 Imagined Native American Savagery. From Hans Staden, The True History of His Captivity, 1557, trans. and ed. Malcolm Letts (1928)

The first invasions were the Columbian voyages, made between 1492 and 1504. Among the indigenous island people, the Spaniards found no monarchs they could recognize, no resplendent robes or great castles. Nor, most important, did they find great quantities of gold or any other precious metal. These conditions, plus the absence of European modesty of dress, an indecipherable language, the absence of books, and no recognizable belief in God, marked these people as savages and gave the Spanish invading armies justification to abuse and enslave them. Without the recognizable trappings of civilization, the Indians barely seemed human, and certainly not worthy of respect. The Spanish did not kill off all the locals for one reason: In the absence of gold, the Spaniards realized that Indian prisoners were the next best possession.

The Columbus Clan in America

Christopher Columbus, an experienced Genoese mariner, son of a merchant and tavern-keeper, led a family that worked hard to profit from the American enterprise. Christopher was a sailor on merchant ships from an early age, and he married a Portuguese noblewoman whose father and brother were mariners and claimed ownership of an offshore Atlantic island. His younger brother, Diego, who sailed with him on his second voyage, tried to be an administrator of Santo Domingo but ended up in jail and then became a monk. Columbus’s legitimate son, Diogo, married Spanish royalty and later was appointed governor of Hispaniola, a job he performed well for 15 years. His illegitimate son, Fernando, was the product of an affair with a woman in Córdoba while he waited for the Catholic kings to decide to back his plan to sail to the Indies. Columbus recognized Fernando, who sailed on the fourth voyage and later wrote a biography of his father. Christopher Columbus died rich in 1506, but he lost many of his titles and grants when his claims about America proved to be exaggerated, and despite all their efforts, his heirs were not able to get them back.

Enslaving the locals provided the colonizers with wealth in the form of free labor and services. This established for the Spaniards a social hierarchy that was organized around racial categories. Europeans were white, Indians were dark, and the label “Indian” swept all the island people into one basket with none of the distinctions of ethnic group or office or blood that ruled local culture before the invasions. Although the islanders fiercely resisted, the Spaniards persisted with superior weapons and grim determination, and the rape, kidnapping, and slaughter went on.

When they arrived in the Caribbean and later invaded the mainland of Central and South America, the Spaniards and Portuguese found distinct ethnic groups. They were awed by the exotic environment, so lush and so beautiful, far different from the countryside of central Spain. They were also puzzled by the absence of cattle and lack of wide roads for transporting commercial goods. They demonstrated a deep disrespect for the customs of the people. The absence of clothing, lack of technically advanced weapons, simplicity of the housing, and seemingly less formal family arrangements, including sexual practices, unnerved the invaders. Above all, they sought to apply the rules of warfare used in that era toward enemies: Those who fell outside the rule of Christian law could be enslaved.

To describe the indigenous people, the Spaniards used the catchall label “Indian,” and they fell quickly into the habit of thinking that all the indigenous people, wherever they lived or however they dressed, or whatever language they spoke, were essentially of the same culture. The Spanish efforts to enslave the island populations were based on informal claims that these defeated people were outside the rules of civilization.

Once European rule was established, colonial officials came to see differences within this so-called unitary indigenous culture and took shrewd advantage of them. No instrument was more important for this strategy than the claim to land. In land-scarce Latin America, many ethnic groups calculated their wealth and status by the amount of land they controlled. Spanish officials learned this, and they leveraged this knowledge to gain allies among the Indians. Some ethnic groups were favored over others when awarding rights or recognition of land claims. These awards resulted in villages that became major administrative centers. In colonial Latin America, privileges tended to go with administrative importance, and administrative importance and size tended to align with ethnicity. Administrative power enhanced groups’ colonial status. In turn, the public behavior of especially powerful ethnicities became identified with colonial culture. Throughout the centuries of colonialism, these divisions strengthened European control.

Despite the hard blows suffered by Indian ethnic groups during the invasion period, many of them remained important in Mexico and Central America, as well as in the Andean highlands. Their privileges in the colonial period were not directly related to their knowledge of Spanish or Portuguese but rather to their administrative status. It helped, of course, to know the colonial language, and they often worked to ensure that someone in the village learned to speak—or much more importantly to write—Spanish or Portuguese. Bilingualism was a powerful tool to keep privileged ethnic groups well connected to the Spanish colonial centers of power. Such centers usually included major haciendas (Spanish landholdings) and mining centers, where colonial officials and economically powerful encomenderos (overlords of Indians) and later hacendados, or landholders (generally cattlemen), and planters (generally commercial growers) would be found.

Encomienda and Colonialism

Encomienda was a fundamental relationship in the system of colonial control in Latin America. First used in the Caribbean, it was like enslavement but different in crucial respects. Encomienda became the answer to a Crown dilemma: how to reward the invaders for their military successes without giving individuals complete ownership of the Indians. The Crown realized that giving up control of the indigenous people would mean that they might all be killed or all the things they produced, including gold, silver, and other goods, would never reach the hands of the Crown. The treasury in Spain would get nothing from possession of the conquered areas. Latin America would be the central possession of the Spanish Crown, but gold and tribute would flow to the Spanish invaders, not to the Spanish treasury.

Meanwhile, missionaries in Spain, with the help of the Pope, saw in the indigenous people a great opportunity to convert a vast population to Roman Catholic beliefs. At a time when the Christian world was in crisis, the missionaries and the Pope persuaded the Crown to help the Church carry out its conversion mission. To meet this need, in 1513 the Crown devised encomienda as a way to accomplish several goals: give the Church partial oversight of the lives of the Indians, give the invading soldiers a reward for risking their lives on Spain’s behalf, and provide a means for forcing the conquered people to work to send gold, jewels, and other goods to fill the Spanish treasury. The conquered people in their villages were assigned “in trust” to those invaders who made claims for rewards as a result of their military victories. The assignment was carried out by the captains of these expeditions, providing that the encomenderos promised to convert the Indians and not enslave them.

Encomienda turned into a form of slavery and segregation. Assignment of whole villages of indigenous people to an encomendero was made based on where the people lived. Most indigenous people lived in villages spread far and away around the main cities of Tenochtitlan in Mexico, Cusco in Peru, and other large centers. At first, the conquering Spaniards were the only recipients. With the approval of the Crown, and depending on the military rank and social status of the individual who requested it, encomienda was awarded for proven military valor in battles against the Indians in the Caribbean islands, Mexico, Central America, Peru, and other parts of South America. The encomendero received all the tribute, labor, and services that the people in specified towns had to offer. The towns and their locations were identified and the encomendero then sent emissaries to those places to serve notice to the locals of their tribute, labor, and service obligations. The details of execution were worked out among them.

In effect, the Spanish encomendero became the lord of the people he held “in trust.” He was expected to provide for their conversion to Christianity, and to defend the colony when the king needed him to do so. The 506 Spaniards who received encomienda in Mexico had an opportunity to become extremely rich. Certainly if all went well, they would never again have to work with their hands. That was the intention of the invaders from the start, and whether the reward came in the form of gold or people made little difference. Furthermore, they expected the reward to be a part of the legacy they would pass on to their descendants. Gold could be passed on to one’s heirs, but inheritance of encomienda threatened the colonial power of the Crown and the Church.

The encomendero usually lived in a city, far from the towns he ruled. Work was overseen by local officials, usually men who had been the chiefs (caciques), those who had overseen local labor before the European invasions. Thus, the ethnic identity of the towns was preserved, especially since the ethnic chiefs were customarily the source of authority people knew best. In addition, the labor of encomienda Indians was done on lands that had been occupied by ethnic groups before the European invasions. Now, however, the produce went to pay the tribute demanded by the encomendero. Agricultural labor to produce corn, beans, cacao, or potatoes was not the only form of labor possible. Mining was another—and to the Crown a far more important—form of labor, as was personal service in the home of the encomendero. Encomenderos took anything they found commercially valuable and set quotas on its production. Other labor included cloth, wool, and dyestuff production, depending on location and local resources.

The differences in the grants of encomienda were great. Hernán Cortés received from the Crown the title of Marques of the Valley (he controlled the towns of the Oaxaca Valley, an enormous region that included all the Zapotec villages), with the right of encomienda over 23,000 tribute payers. Later, Pedro de Alvarado awarded himself and his brother, Jorge, the largest number of tribute payers in Guatemala. The two leaders had villages containing more than 1,000 people. Another six captains were given the tribute of pueblos containing more than 500 people. While considerably smaller than the grant made to Cortés, the production of cacao (chocolate) in these towns meant considerable wealth for the encomenderos.

The Spanish invaders were not terribly concerned about the ethnic consequences of encomienda. If an odd ethnic village was coincidentally lumped with the majority ethnic villages that were awarded to one encomendero, so be it. Ethnicities were divided when the need arose, and the consequences were ignored. The Spaniards did not give much consideration to questions of ethnic harmony, a matter that was made especially important for the indigenous

Map 2 Colonial Latin America, Political Organization. From Burkholder & Johnson, Colonial Latin America, 4th edition (2001), Map 4, p. 257. By permission of Oxford University Press, USA.

people by the devastating effects of the conquest. Nor did the encomenderos live among the indigenous people from whom they received tribute and labor. With few exceptions, such as those individuals who did personal services for them, encomenderos rarely saw the people from whom they received tribute. The Spanish encomenderos preferred to live in the colonial centers where Spanish social life was important. This practice meant that two societies developed in the Spanish American colonies: the world of the Indians and the world of the Spaniards. The former, called the “república de los indios,” was the world in which only Indians lived and socialized. The latter, dubbed the “república de los españoles,” was inhabited by only the Spaniards and their servants.

Encomienda came under attack from the Crown almost from the beginning of its use. Pressured by the Church, and fearful of the power of the encomenderos, the Crown sought to limit the assignment of encomienda to the life of the first invaders who received it. The invaders wanted to keep this source of wealth intact and to pass it on to their descendants. In some cases they succeeded but most (and finally all) times when an encomendero died without heirs, or without a will, the Crown seized the Indians. Those people became wards of the state under the control of colonial officials. Also, as the indigenous population died out, encomienda declined.

Land Claims, Ethnic Differences, and Colonial Courts

At the outset of the colonial venture in Latin America, the Spanish and Portuguese monarchs issued licenses to individuals to claim lands and other valuables in the Western Hemisphere. The invaders agreed to claim the lands and goods in the name of the Crown. The crowned heads of Spain and Portugal thus became the owners of all those lands, and they refused to cede ownership of them to the invading soldiers as rewards for their deeds. If they did so, they could easily lose control of the distant colonies. Thus encomienda, not a land grant, was the preferred royal method of reward for the invasions. In turn, the encomendero collected a periodic tribute payment, or a head tax, from the people assigned to him in encomienda. Tribute was the penalty indigenous people paid as punishment for being conquered. The needs of invaders, the Church, and the crown all were served by the encomienda compromise.

Once the first generation of invaders died off, their descendants faced a problem. They could no longer justify control of the Indians because of valor in battle. Additionally, other Spaniards migrated to the colonies in search of wealth. They too sought encomienda and other privileges. New justifications had to be found. Blood descent from one of the original invaders was one of those. Other justifications were given, but the Crown resisted. Indeed, many encomiendas passed into the hands of the colonial state as invaders and their descendants died. At that point, the state began using the indigenous people for its own purposes, especially mining. It also upheld the system of social segregation created by encomienda.

Descendants of encomenderos adjusted to the loss of encomienda by finding other ways to preserve the family wealth. One of those ways was to make a claim for land. How could officials award land to Spanish claimants when the Crown owned the land? With the decline in native population, like the encomenderos, the Crown found itself with declining revenues. Ways were sought to make the colonies more productive for the Spanish treasury. The answer was another compromise: Land was not exactly sold to Spanish colonial claimants but rather granted in a form called merced. The Crown conceded ownership of the land, and in fact many of the grantees became immensely wealthy hacendados. The grantees thought of themselves as a privileged sector...