1 The shape of British politics

This country’s distinctive contribution to civilisation has been the development of stable institutions of representative government.

(Daily Telegraph editorial, 19 December 1997)

The British Constitution has always been puzzling and always will be. (The Queen, early 1990s, quoted in Peter Hennessy, The Hidden Wiring, 1995, p. 33)

INTRODUCTION: WHY POLITICS MATTERS

‘Somebody has to do it.’ This is the best explanation, and justification, for politics and politicians. They may not always be nice, but they are necessary. All societies have to make policy choices, confront problems, resolve conflicts, handle disagreements, decide ‘who gets what, when and how’ (as one famous definition of politics put it)—and this is what politics and politicians are all about. If we all agreed about everything and had the same interests we could perhaps replace messy politics with simple administration. At the time of the Russian Revolution, Lenin argued that the communist future would be like this! In the real world, politics is part of the furniture.

This is why, from Aristotle onwards, it has often been seen as a human activity of supreme importance. In a famous essay, Bernard Crick celebrates politics as ‘a great and civilising human activity…something to be valued almost as a pearl beyond price in the history of the human condition.’1 This may seem far removed from the way in which politics and politicians are frequently regarded in practice— where the focus is sometimes more on swine than pearls—but it is all the more reason to remember the ideal. At its best, politics is the means whereby human beings living in societies co-operate to negotiate their conflicts, tackle their problems and pursue their goals. At its worst, it is the scene of disorder, strife, corruption and tyranny. The modern world has witnessed the full range of political experiences.

THE CONTEXT OF BRITISH POLITICS

This book is about Britain, but the shape of British politics necessarily carries the imprint of the political experience of this wider world. As we shall see, there is much that is distinctive about the British political tradition (for example, a culture of liberty that predated democracy and was rooted in the common law, and the assertion of the rights of Parliament as the result of the constitutional struggles of the seventeenth century), but there is also much that can only be understood in the wider context of the politics of the modern world. Britain both contributed to this experience and drew from it. This remains the case today. Different political systems have to confront many of the same problems and feel the impact of many of the same forces, but they are also the product of particular histories, traditions and cultures. That is why they are different. They are organised differently (compare the federal constitutions of Germany, the United States or Australia with the unitary state in Britain), operate differently (for example, coalition politics is normal in much of Europe but abnormal in Britain) and behave differently (it has been said that a disgruntled Frenchman blocks the roads, a disgruntled American goes to court, and a disgruntled Englishman lobbies his MP). Such differences define the shape, flavour and character of political systems.

The historian Eric Hobsbawm has described the shaping forces of the past two centuries in Europe in terms of a ‘dual revolution’ (The Age of Revolution, 1789– 1848). One revolution was the set of ideas associated in particular with the French Revolution of 1789, which provided the modern world with its distinctive political language of rights, liberty, democracy, equality, nationhood and constitutionalism. The other revolution was the industrial one, in which Britain was the pioneer, that transformed the way in which people lived and worked. In combination, these two revolutions shaped much of the politics of western Europe (and beyond) in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. They spawned the political ideologies, social movements, national upheavals, reforms and revolutions that are the history of this period. Yet this shared context produced very different national histories; and it included the distinctive experience of Britain. Having got their own revolutionary moment safely out of the way in the seventeenth century, the British managed to reform their way to democracy in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

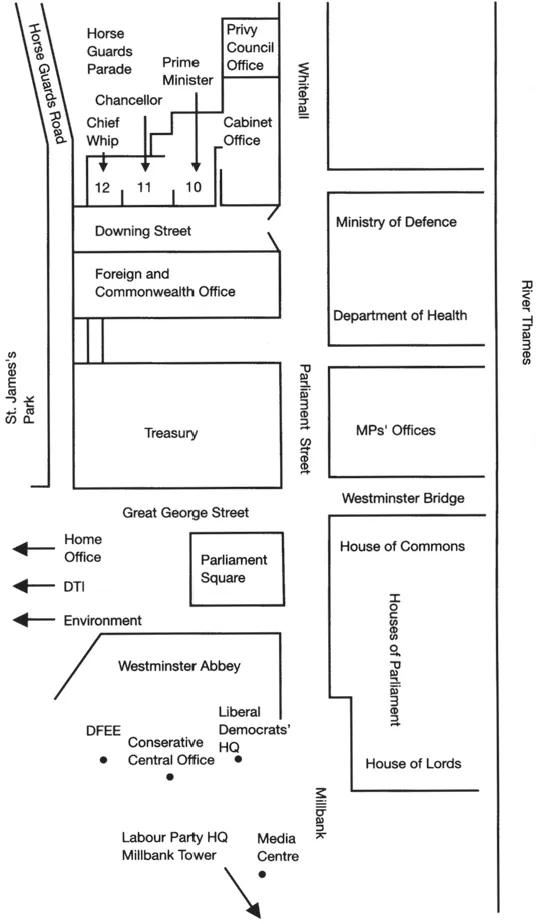

We should not make this story sound too smooth, as there was no shortage of crises and conflicts, but it is nevertheless a story of accommodation and adaptation. An old society, with its established political institutions, had to meet the challenge of new social forces and new political demands. The fact that this happened through a process of integration and incorporation, rather than through revolutionary upheaval, means that the British political system was never pulled up by its roots and reconstructed. This is regarded by some as a great blessing; by others as a considerable curse. Whatever view is taken, it is a shaping fact of modern British politics. It explains why the institutional landscape of British politics—the monarchy, the Commons, the Lords, the civil service, the Cabinet, the Prime Minister, the procedures and the pageantry—looks so unchanging. Of course it has changed in practice, and any realistic picture of the British political process now has to include other institutions too (notably those of the European Union), but there is also a remarkable continuity. The ‘village’ of Whitehall and Westminster, the small patch of central London where the key political institutions are to be found, continues to provide the hub of the political process (Figure 1.1). Even the pattern of the political year has its particular and distinctive shape. Individual years bring their own events and crises (when asked what were the most difficult issues facing him as Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan replied ‘events, dear boy, events’), the cycle of general elections provides the larger framework—at intervals of no more than five years, but there is always the underlying annual rhythm of political life (see box below).

Figure 1.1 Britain’s political village

The British political year

| ^^ September/early October | To the seaside, for the annual party conferences (Liberal Democrat- Labour and Conservative, in that order) |

| Mid-October | Parliament reconvenes to complete 'overspill' business of the session |

| Late October/early November | State opening of Parliament. Queen's Speech outlines the Government's legislative programme for the new session |

| November | Pre-Budget report by Chancellor of the Exchequer, with assessment of the economy and spending plans |

| December | Private members' bills announced after ballot |

| January | Honours list announced and public records released under 30-year rule |

| February | Budget preparation and lobbying |

| March | Chancellor delivers Budget, with its tax and spending announcements |

| May | Elections to local council (and, every four years, to the devolved assemblies in Scodand, Wales and Northern Ireland; and, every fifth year in June, to European Parliament) |

| Jline-Jufy | Scramble to get legislation through all its stages before the end of the parliamentary session |

| Late July | Parliament goes on holiday for its long summer recess (and the 'silly season' starts in the press to fill the gap) |

We can only understand what is distinctive about the British political tradition if we begin by setting it within the wider context referred to above. Britain shared in the ‘dual revolution’ that shaped the modern world, but did so in a particular way that reflected its own history and character. It reformed its way to democratic politics. Its industrial leadership produced a strong labour movement, but the influence of Marxism on it was much weaker than elsewhere in Europe (owing ‘more to Methodism than to Marx’, it was often said). Social class divisions were profound, shaping much in British society and politics, but without bringing revolutionary consequences. It was a multinational state, but— with the massive exception of Ireland—avoided the bog of nationalist conflicts. It had religious differences, but outside Ireland these were not of a scale or nature to provide the basis for a sectarian politics of religion. While sharing some of the conditions that fostered it, Britain did not succumb to the snare of fascism. These are just some leading examples of the way in which modern history has been felt in Britain in a particular and distinctive way. The same continues to be true. Globalisation and technology are transforming the world, but—just as with the dual revolution earlier—the political impact is not uniform everywhere and meets the force of local traditions. Perhaps the clearest example of this in Britain is the process of European integration, the running sore of recent British politics, which can only be understood as a political issue in terms of the legacy of a particular history.

APPEARANCE AND REALITY

Before summarising some of the features that define the modern shape of British politics, two warnings are needed. The first is about confusing appearance with reality. Things are not always what they seem. This warning is particularly necessary in relation to a political system which gives the appearance of such continuity. ‘An ancient and ever-altering Constitution’, wrote Walter Bagehot in the middle of the nineteenth century, ‘is like an old man who still wears with attached fondness clothes in the fashion of his youth: what you see of him is the same; what you do not see is wholly altered.’2 Institutions may look the same as ever, they may go through the same motions, they may even claim to be the same; but they may in fact have become quite different. Functions and powers may have gone elsewhere. Bagehot advised his readers to distinguish between the ‘dignified’ and the ‘efficient’ parts of the political system—the difference between appearance and reality—advice that should still be followed.

In looking at the political process in its various aspects in the chapters that follow, this question of appearance and reality—and how formal descriptions may be different from actual functions—is one to be kept constantly in mind. The British system of government is formally described as the ‘Crown-in- Parliament’, but this is not very useful as a description of how it actually works. It reflects the terms of a 300-year-old constitutional settlement between monarchy and Parliament (also reflected in the words of the rarely sung but much more interesting second verse of the national anthem—May she defend our laws/And ever give us cause /To sing with heart and voice/God save the Queen—with its sly reminder of the conditions upon which the monarchy exists); but it tells us next to nothing about the real nature of the modern political process. Indeed, and worse still, it can work to obscure this. The monarchy has lost its political power (except in the sense, as Bagehot also observed, that symbolic and decorative institutions perform political functions too), but it is not Parliament but the executive that has now acquired this power. This was not yet true in the nineteenth century, but it has become abundantly clear with the development of disciplined party government in the twentieth. The famous doctrine of ‘parliamentary sovereignty’, that is supposed to be the core concept of the British political system, now obscures more than it reveals. It is not Crown-in- Parliament but Executive-in-Party that now provides the best description and efficient secret of modern British government.

CHANGE AND CONTINUITY

Then there is the second warning, in addition to the problem of appearance and reality: the issue of change and continuity, the need always to distinguish between the enduring features of the political process and those that are changing. This can often be very difficult. The environment in which the political system operates is in constant flux, at some periods dramatically so, and it is inevitable that this will reshape the political process. It is only necessary to consider some of the striking ways in which British society has changed in the period since the end of the Second World War (Table 1.1) to see that such changes will bring consequences for political life and institutions. The growth in the role of the state during the course of the twentieth century, especially in the Second World War and the post-war development of the welfare state, makes the point well (Figure 1.2). This is also a reminder of how underlying trends, external forces, inherited policies and established expectations circumscribe political life. Politicians may speak a language of new departures and bold initiatives, but this meets a reality of powerful continuities. Thus the Conservatives came to office in 1979 with a mission to cut taxes and reduce the size of the state; when they left office in 1997, taxes were 3 per cent higher as a share of GDP. Yet change there had clearly been, notably in the massive privatisation programme, and the post-war trend for the ratio of central government expenditure to GDP to increase was checked (falling from 44 per cent in 1979 to 41 per cent in 1996) and the size of the civil service reduced. The balance between change and continuity at any period is notoriously difficult to identify, as are the forces bearing down on each side, and often becomes clearer only much later.

What this means is that all generalisations about the po...