![]()

Section II

Approaches to the Study of Sociolinguistics and Second Language Acquisition

![]()

4

Social Approaches to Second Language Acquisition

The first chapter of this book provided an introduction to communicative competence and the concept of sociolinguistic competence. We saw that to be fully competent users of a language we must be able to properly interpret and produce the elements in language that vary from one speaker to another, one context to another, and one geographic region to another. Likewise, Chapters Two and Three provided an overview of the field of sociolinguistics and the types of inquiry undertaken in that field. We saw that languages vary at all levels of the grammar and that the manner in which we produce language is influenced by a host of individual and group factors. In fact, the very group with whom we identify and how this group is defined has been the focus of extensive research and theory building. What is clear from work conducted in the field of sociolinguistics is the unifying focus on social aspects of language. In other words, sociolinguistics views language use as a social activity that allows speakers to relate to one another in a variety of ways and accomplish a range of communicative tasks. For the remainder of this volume we turn our attention back to second language learners and the many ways in which knowledge of sociolinguistics may improve our understanding of second language acquisition.

WHAT IS A SOCIAL APPROACH TO SECOND LANGUAGE ACQUISITION?

What may not have been clear from the introductory chapters is that despite the widely recognized multifaceted nature of communicative competence and the focus on social elements in sociolinguistics, the dominant tradition in research on second language acquisition has tended to focus on the linguistic elements of mental grammars. Such approaches are generally known as cognitive approaches to language acquisition, as a result of their focus on cognition and mental structures (Atkinson, 2011a). Specifically, cognitive approaches focus on linguistic knowledge as an independent system, generally believed to contain innate linguistic information, and on the internal, mental processes of language acquisition, which are ultimately understood to be a product of human cognition. These approaches are often contrasted with social approaches, which might be broadly understood to include any approach that incorporates social factors in its account of linguistic knowledge and language acquisition. Nevertheless, we use the term “social approaches” in the current chapter to denote those approaches that place social elements of language learning and language use at the forefront and prioritize the examination of the influence of social context on language.

Despite the abundance of research mentioned in Chapter One that points to the importance of social factors in influencing second language acquisition and use, studies that focus on the connection between models of learner language, acquisition, and use, on the one hand, and the effects of various social factors, on the other hand, are quite scarce. In fact, in their 1997 seminal article, Firth and Wagner noted that the predominance of cognitive-oriented perspectives in second language acquisition research has led to bias or “imbalance” in the application and development of theoretical frameworks and methodologies in the field. Their claim was that social factors had been neglected, and their work served to foster additional research on the social aspects of language learning. Their paper met with a wealth of response, some sympathetic and some contrary, but all of which led to insightful expansions of what may now be known as the cognitive-social debate, or more dramatically, the cognitive-social divide (e.g., Block, 2003; Gass, 1998; Hall, 1997; Kasper, 1997; Long, 1997). Perhaps the most important result of their work, however, was that it led to greater interest in the many ways in which social contexts and social characteristics may influence language learning and language use. Ten years later, a special volume of the Modern Language Journal (2007) was published to assess the degree to which the state of research on social approaches to second language acquisition had changed. Authors in this volume note several important accomplishments, such as the prioritization of sociocultural and contextual factors in many studies (Swain & Deters, 2007), a growing body of empirical evidence on the relationship between social context and second language use and acquisition (Tarone, 2007), and a reconceptualization of the learner as a legitimate user of the target language (Mori, 2007). Nevertheless, there were still many who voiced concern at the lack of change in certain areas, including the integration of social approaches into the second language classroom (Lantolf & Johnson, 2007) and the surface-level conceptualization of learner identity (Block, 2007).

It is clear that while sociolinguists share a common set of goals in exploring language use, second language acquisition researchers have multiple goals, and these can, at times, appear to be in conflict. The goal of the current chapter is neither to provide an in-depth account of any single social approach nor to weigh in on the debate about the social-cognitive divide. Instead, we seek to examine the scope of social theories of second language acquisition, their contribution to our knowledge of language learning in general, and the shared characteristics of these approaches as a whole. Finally, it is important to point out that the range of social theories included is quite broad and these theories are not necessarily limited in scope to the acquisition of sociolinguistic competence or of sociolinguistic variation.

EXAMPLES OF SOCIAL APPROACHES TO SECOND LANGUAGE ACQUISITION

As stated previously, the current chapter highlights models or approaches that place social influences on language learning at the forefront. In some cases, the examples selected are viewed as classic cases that serve as the foundation for current research, and in other cases they remain highly productive strands of research. For each approach, we provide an overview, identifying the ways in which that model accounts for the impact of social factors and the claims made under each framework regarding the role of social (in addition to other) factors in learning a second language. Next, we provide a snapshot of the manner in which research on second language acquisition was conducted under each approach. The review concludes with a critical evaluation of these models.

The Acculturation Model

Long before Firth and Wagner’s (1997) call for more research investigating the social dimensions of second language acquisition and use, some researchers were already turning to the “social side” in search of more comprehensive explanations of differential success among learners. For example, John Schumann’s work led him to develop the Acculturation or Pidginization Model of second language acquisition (1978a, 1978b). Schumann (1978a) observed that over the course of 10 months, one untutored Spanish-speaking learner demonstrated minimal success in the development of the English negative, wh-questions, inversion of yes-no questions, inflectional morphology, and auxiliaries of differing functions (e.g., do-support, progressive, perfect, modal). This learner, Alberto, became the focus of an extensive case study carried out by Schumann (1978a) to examine both the linguistic and the extralinguistic aspects of Alberto’s acquisition of English. From the linguistic analysis, Schumann showed how Alberto’s simplified and reduced English shared several features with pidgin languages. One example was the tendency for Alberto to use no to create negative utterances. Another was the lack of inflectional morphology. This type of cross-linguistic comparative analysis led Schumann to conclude that Alberto spoke a pidginized English, but the question remained as to why Alberto’s English was simplified and reduced.

Drawing on Smith’s (1972) work related to pidginization and language socialization, Schumann (1978a) proposed that Alberto’s use of English was “restricted” to the fulfillment of basic communicative functions, and this led to the development of a simplified and reduced variety of English. Schumann further pinpointed the origin of this “functional restriction” as Alberto’s social and psychological distance from speakers of the target language community. In other words, Alberto’s lack of acculturation to the target language group served as the reason why his English showed minimal development. Schumann (1986) defined acculturation as “. . . the social and psychological integration of the learner with the target language group” (p. 379). In his model, social and psychological factors have the potential to influence contact between the learner and speakers of the target language group. What is more, the integration of both sets of factors is essential for acquisition of the target language. In other words, successful acquisition is dependent on acculturation to the target group both socially and psychologically.

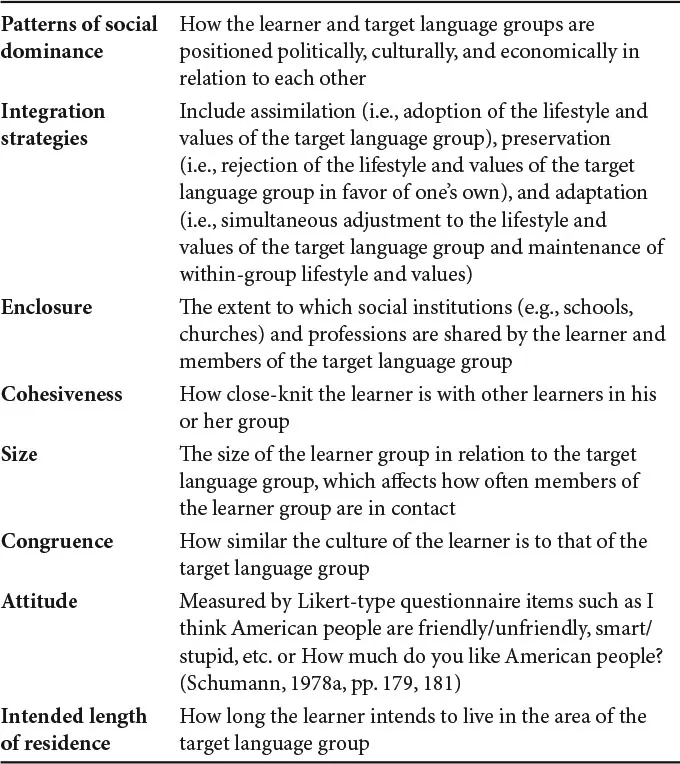

One essential element of Schumann’s model is how he characterized this social and psychological distance. The factors related to social distance in the model have their origins in the field of sociolinguistics as well as work related to bilingualism and ethnic relations (cf. Schermerhorn, 1970). Schumann (1978a, 1986) identified several constructs, such as patterns of social dominance, as factors that could potentially influence the degree of contact between the learner and members of the target language group. The full list of factors included in his model is summarized in Table 4.1, along with a definition of each.

Schumann (1986) generated hypotheses for second language learning based on each of the factors summarized in Table 4.1. For example, Schumann (1986) hypothesized that the tighter the cohesion of a learner group, the less likely learners within that group would be to mingle with speakers of the target language group. Opportunities for contact with the target language group would be minimized, which in turn would limit interaction with speakers of the target language and ultimately impact the extent of acquisition of the second language. It is important to note that these factors do not necessarily operate in isolation from each other, nor are they absolute. Instead, each lies on a continuum, for example, from more to less dominant or subordinate (in the case of patterns of social dominance) or from having a more positive to a more negative attitude toward the target language group. These factors collectively determine the degree of social distance between the learner and members of the target language group.

Among the psychological factors Schumann (1986) proposed were language shock, culture shock, motivation, and ego permeability, all of which have the potential to influence contact between the learner and the target language group. This, in turn, could influence the acquisition of the second language. Ego permeability is similar to the notion of an affective filter as proposed by Krashen (1982; see also Chapter One), and the term captures the idea that inhibitions about aspects of the second language may lower one’s “openness” to available input, which affects one’s ability to acquire the language.1 Like social distance, psychological distance lies along a continuum, and the relevant factors taken together determine the degree of distance that exists between the learner and members of the target language community.

TABLE 4.1

Factors believed to impact social distance (based on Schumann, 1986)

Returning to the Acculturation Model as a whole, we recall that the integration of the social and the psychological, each containing their own “cluster” or set of factors, is essential for acquisition. Schumann (1986) envisioned the outcome of second language learning in a naturalistic context as the result of the extent of acculturation to a target language group. In essence, acculturation influences both the quality and quantity of input and interaction available, and this, in turn, influences language learning. Thus, the Acculturation Model affords an essential role to social factors in the process of second language acquisition.

Research Methods and the Acculturation Model

To account for development in the linguistic structures of interest, researchers who had adopted this model employed a mixed elicitation methodology. More controlled elicitation tasks such as imitation and the Bilingual Syntax Measure (Burt, Dulay, & Hernandez-Chavez, 1975) were used, in addition to less controlled elicitation methods, such as spontaneous conversations. Schumann’s (1978a) seminal study also included preplanned sociolinguistic interactions. During these preplanned interactions, Schumann accompanied Alberto to a variety of social encounters, such as ordering food at a restaurant, and observed his use of the grammatical structures under study. In addition to collecting examples of speech produced under varying conditions, the social and psychological factors of interest were measured as well. Generally, a combination of fieldwork observations and results from detailed questionnaires completed by each participant were examined. Questionnaires were often specifically aimed to gauge learners’ attitudes toward members and practices of the target language community as well as their motivation for learning the language.

One key challenge for researchers interested in acculturation was determining how to assess the factors proposed to influence psychological distance between the learner and the target language group. Schumann (1986) pointed out that creating measures for notions such as language or culture shock and ego permeability presented a major obstacle for researchers attempting to characterize these factors empirically. Masgoret and Gardner (1999) detail an attempt to measure “acculturative stress”, or the degree of difficulty immigrants in Canada experienced as a result of their move from their home country (Spain). This measure, assessed via a written questionnaire using 19 Likert-type statements, showed that only length of residence correlated with acculturative stress: Those who had been living in Canada longer had lower levels of acculturative stress. Acculturative stress was not reported to correlate with other variables, such as self-reported and objective measures of language proficiency, assimilation, or integration. This study therefore offered evidence that, contrary to Schumann’s model, stress associated with acculturation to the target language community does not appear to relate directly to language contact and, subsequently, to language acquisition. In response to Schuman’s hypothesis, a wealth of studies were conducted, some lending support (e.g., Kitch, 1982; Maple, 1982) and others providing counterevidence to the hypothesis (England, 1982; Kelley, 1982; Schmidt, 1983; Stauble, 1981). Although this hypothesis is not generally used in contemporary research, it did provide the foundation for investigations modeling the relationship between cultural identification and development of second language pronunciation (Lybeck, 2002) as well as the characterization of intercultural interaction and its relationship to attitudes toward the second language among sojourners or temporary residents (Culhane, 2004).

Accommodation Theory

Like the Acculturation Model, Speech Accommodation Theory attempts to account for the ultimate success that second language learners demonstrate in the acquisition process. More generally, Speech Accommodation Theory is a sociolinguistic theory that explores why individuals adjust their speech during social interaction. As described in earlier chapters of the current volume, speakers modify the language they produce according to, among other factors, the characteristics of the person to whom they are speaking. For example, most people would not talk to their grandmother the same way they would speak with a sibling. Proponents of Speech Accommodation Theory add an additional layer of complexity. That is, speakers also adjust speech (or not) to that of th...