![]()

1

THE OLYMPIC GAMES

An ephemeral opportunity for cities

Olympic legacies are one of the unsolved mysteries surrounding the aftermath of the world’s largest sporting event. While many host cities plan for valuable legacies, what exactly they are and how they came into being, are widely debated questions among international scholars, politicians, urban planners and sports enthusiasts. True legacies only emerge after the Games and remain largely unexplored as the spotlight of the event shifts to the next host. One fact, however, is indisputable: the Olympic Games provide the host city with an unprecedented opportunity for change. Within a few years, cities undergo a transformation stimulated by the hope for economic growth, a world-class image, enhanced connectivity and urban regeneration. Yet whether these desirable outcomes or their negative side-effects remain in host cities after the Games have left are “known unknowns”* (Horne 2007: 86). In this book, I appraise the Olympic Games and their effects on metropolises as momentous opportunities to realize ambitious urban and regional goals. I find that the International Olympic Committee (IOC) can influence these local goals, sometimes creating – but also squandering – valuable opportunities for the host city. Unless local governments take proactive steps to ensure that the urban and transportation decision-making does not serve only the event’s short-term needs, city planners will not get the transformation and long-term benefits they had hoped for.

Yet it is those hoped-for legacies that are the typical rationale for most residents to back the bid. In a nutshell, legacies are consequences of mega events. Pioneering works on legacies categorize outcomes of the world’s largest events (see Cashman and Hughes 1999; Clark 2008; Gratton and Preuss 2008; Poynter 2004; Preuss 2004; Ritchie 1984). The most common categories are cultural (Roche 2006), economic (Preuss 2004), political (Burbank et al. 2001), physical (Essex and Chalkley 2008), psychological (Malfas et al. 2004), and social (Horne and Manzenreiter 2006). Olympic legacies penetrate different geographical spheres, and can be positive or negative, beneficial or detrimental, tangible or intangible, visible or invisible. Their basic characteristics however, are intrinsically the same: they remain in the host cities’ Umwelt for several subsequent years, decades and sometimes even centuries. Among these legacies, the theme of urban renewal has gained exploding importance as more and more local governments attempt to use the Games as catalysts for urban regeneration. For this book, I focus on the process through which legacies were created in transport and urban systems paying particular attention to those influences that are broadly stimulated by the Olympic Games as an event; these influences were either imposed by the IOC via explicit and implicit requirements during the pre-Olympic preparation stages, or – equally important – by city governments driven by ambitious aspirations to win and stage the “best Games ever.”*

By examining the urban planning trajectory of Barcelona, Atlanta, Sydney, Athens, London and Rio de Janeiro with a particular lens on the IOC, I hope to provide a new perspective and a better understanding of the urban and transport legacies remaining in cities post-Olympics. The book draws on a unique set of data, given that I had access as an IOC Fellow to the archives containing the internal communications between the IOC and the hosts. These archives are under a 25-year embargo. With time and persistence, I also established a working relationship with the only transport advisor, appointed by the IOC in 1999, tasked to evaluate all Olympic bids in terms of transportation. With his assistance, I was able to conduct personal interviews with planners in charge of transport and urban development in Olympic host cities. Continuing my Olympic journey, I lived in Barcelona, Atlanta, Sydney, Athens and London for several months each, conducting interviews, archival analysis and site visits. I cross-compared and traced the creation of urban and transport legacies over several decades before and after the Games. In essence, I believe there are two important stories to tell.

The first is about the potential power that the IOC can exercise on host cities, thereby influencing the creation of legacies. The typical rhetoric surrounding the decision to bid for the Olympics almost always emphasizes the legacy impacts of the Games, but the dynamic that I document in this book is that cities frequently give priority to satisfying the short-term demands. Location choices for Olympic activities coupled with transportation demand peaks require certain alterations to metropolitan regions. Therefore, the IOC sets forth requirements to which bidding cities adhere, but frequently exceed. Either way, infrastructural investments have become a necessity to stage successful Games. The degree to which Olympic requirements make the cities deviate from their original master plan, however, varies greatly. I attribute this degree of deviation to three factors. The first factor is that over time the IOC became more knowledgeable about handling Olympic passenger travel because of previous hosts’ mistakes and successes. Hence, the committee imposed additional and more stringent requirements on cities over the past three decades. The second factor is that the more the IOC doubted the city could handle the Olympic transport, the more pressure it exercised on the city to comply with their requirements. Through this process the host cities created Olympically driven legacies. Even though the introduction of the IOC’s requirement for bidding cities to justify expected legacies beyond the Games could have reversed the trend of Olympic legacies that do not fulfill long-term functions beneficial to the host city, Rio de Janeiro’s bid lends evidence to the contrary. This leads me to the third factor: some host cities have ignored much of their strategic urban planning goals in favor of winning the bid. This might be due to not having an urban master plan in place or focusing on other legacies, such as economic growth or a global image, at the expense of urban legacies.

The second story is about the careful integration of Olympic requirements with urban master plans to create long-lasting and beneficial urban and transport legacies. Past host cities frequently failed to take long-term advantage of the Olympic event, notwithstanding what they originally thought they would do. To the extent that cities have been able to gain sustainable advantage from hosting the Olympics, it is because there has been an alignment of their long-term planning perspective and the way they used the Olympics to improve their transport systems. My measure of alignment (between the IOC requirements and the metropolitan strategy) is the extent to which the city deviates from its original plans because of the Games.* Any deviation from the original city plans provides evidence for the role the Olympics play in creating legacies. The deviation can be driven by both: the host cities’ new Olympic priorities and the IOC requirements. I acknowledge that there might be other influences that change the original city plans in the run-up to the Olympics. This possibility, however, is highly unlikely due to the host city contract † and the immovable deadline the city faces in preparing for an event of such magnitude in only seven years. My conclusion is that if cities are not very careful to create and protect their goals, then the Olympic urban legacy will actually be quite minimal.

The creation of urban legacies

Without a doubt, the Olympic Games affect urban planning, while the legacies created in the process of staging the world’s largest mega event remain in their host cities for decades. Particularly influential for residents are the infrastructural legacies in the host’s urban environment as the city gets permanently transformed. Especially, “the Olympics& have an immense impact on the urban image, form, and networks of the host” (Short 2004: 25). Scholars (Coaffee 2007; Gold and Gold 2007; Jago et al. 2010) along with the IOC, frequently reiterate the importance of planning infrastructure not only for the mega event itself, but also for the city’s urban trajectory to avoid white elephants.* The message for planners is clear: use the Games’ catalytic momentum for urban development irrespective of the Olympics.

The desire of host cities to create urban legacies for spatially focused regeneration and upgraded transportation networks is not a new phenomenon. Over the last half century, cities have endeavored to recreate their urban spaces using the Olympics as a powerful catalyst for urban change. Historically, the first Olympic Games to have a metropolitan-wide impact were the 1960 Rome Olympics. The bi-polarity of the two Olympic Zones (Foro Italico and Zona E.U.R.) stimulated architectural creativity and required coordination across city quarters. The following two Games, Tokyo ’64 and Mexico City ’68, were staged in mega cities and by far exceeded the logistical demands of previous Games on the hosts. Munich ’72 and Montreal ’76 were conceptually similar; both wanted to shine with new urban concepts and new technological innovations. And both encapsulated the Olympics away from their metropolitan region. Montreal’s investments in massive Olympic constructions resulted in a billion-dollar deficit to the city, thereby having a deep impact on the following two hosts. Moscow ’80 and Los Angeles ’84 basically remained on their urban trajectory, allowing the Olympics little interference in their future urban development. Reviving the power of the Olympics in restructuring urban areas, Seoul ’88 rediscovered the true potential of the catalytic Olympic effect, exceeding any previous urban development efforts in scale and magnitude.

As pioneers in their analysis of the Olympic Games and urban development, Stephen Chalkley and Brian Essex distinguished four phases of urban infrastructural development related to mega events over the past 100 years, showing an increasing scale of impact, organizational effort and international attention (Chalkley and Essex 1999; Essex and Chalkley 2004). At the same time, they also observed an increasing mismatch between the promises cities are willing to make in the pursuit of hosting a mega event and what the city needs for its future. The cities, given the imminent publicity and world-wide interest focused on the Games, “invest extravagantly in unnecessary infrastructure” (Essex and Chalkley 2002: 12).

Following these early explorations, attention has shifted away from infrastructure (except stadiums) towards the political process among local governments and grassroot groups to seize the event opportunity for their own good (Cochrane et al. 1996; Owen 2002). For example, Preuss (2004: 1) noted that mega events offer a “unique opportunity for politicians and industry to move hidden agendas” by fast-tracking the decision-making process (see also Cashman 2002; Hiller 2006). This frequently leads to the exclusion of public participation (Hall 1989; Lenskyj 2002). Along with this exclusion came the shift of public resources from long-term investments like education to short-term needs of the event, such as imaging functions (Hall 1996; Jago et al. 2010; Searle 2002). A further controversy in using mega events as a strategy for urban renewal revolves around the discussion of the beneficiaries. Academics have argued that rarely have any improvements benefited citizens (Andranovich et al. 2001), and if they did, they benefited the wealthy (Eitzen 1996, 2002). Hence, Ruthheiser (2000) and Lenskyj (2002) suggested that mega events as such may serve to exacerbate social problems and deepen existing divides among residents.

Focusing back on urban development legacies, John R. Gold and Margaret M. Gold’s (2007, 2010) ground-breaking books revive the discussion on urban development, city agendas and legacy creation. By retelling the stories of Olympic host cities, some researchers reflect on the regenerative power that the Games can have on urban areas (for example, see Coaffee 2007; regeneration also emphasized in Poynter and MacRury 2009). The host cities’ desire to use the Games to revamp tangible legacies, in particular urban regenerations, has become a mainstream topic in the legacy debate. So far the literature has ignored a detailed view on the role of the IOC in planning these desired legacies, because access to data, interviews and non-IOC-controlled insights are incredibly hard to come by. Frequently described as exercising “shadowy geopolitics” (Cochrane et al. 1996: 1323), or as a “self-perpetuating oligarchy immune from democratic accountability” (Short 2008: 325), the intriguing processes of why and how the IOC can influence city planning has largely remained unexplored.

The creation of transport legacies

In particular, transport requires significant planning efforts, and can – if well planned – remain as a lasting legacy in hosting cities (Hiller 2006). The Olympic Games, like other extreme events, set passenger peak demands on transport systems of host cities (Kassens-Noor 2010a). Additional capacity is needed for millions of people, as Olympic peak loads can reach up to 2 million additional person trips per day (Bovy 2009). To manage these passenger peak demands, new transport agencies and communication structures among local transport agencies are created and new operational policies implemented, using a variety of traffic and transport management strategies (Kassens-Noor 2010b). During the Olympic Games, a commuting shift to public transport requires a myriad of additional cars, trains and buses (Hensher and Brewer 2002; Minis et al. 2009). In addition, the transportation system becomes highly vulnerable and contingency plans are a prerequisite for staging the event successfully (Minis and Tsamboulas 2008). Despite hopes to alter residents’ travel behavior in the host cities, Olympic short-term changes usually do not translate to permanent ones. While strides have been made to uncover the operational complexity of Olympic transport, research on accessibility and mobility for special events is still in its infancy (Robbins et al. 2007).

Infrastructural investments in transport systems to prepare for Olympic peak demands have become a necessity to successfully stage the modern Games. Mega events lead to investments in public transportation, road construction and airport expansion; in return these necessary improvements provide the host city with a better quality of life, significant travel time savings, more transport capacity and more attractive transit modes (Bennett 1999; Christy et al. 1996; Getz 1999; Preuss 2004; Syme et a l. 1989). Therefore, events can be planning instruments for urban transport development, such as clearing congested areas or re-organizing transport systems (Rubalcaba-Bermejo and Cuadrado-Roura 1995). Improved transport is a potential benefit frequently mentioned in bidding files and used as a claim to counter potential costs and burdens to the hosting community (Cashman 2002). In sum, transport systems need to be prepared for the Games, whereas the necessary alterations of the transport network remain as tangible legacies in host cities. These legacies can potentially enhance urban transport to accommodate future growth and be a stimulus to change the way people travel.

Planning Olympic legacies in four hosts and two future hosts

To date, the Games not fitting a planning model (Essex and Chalkley 2005), the frequent creation of white elephants (Gold and Gold 2007) and the involvement of the IOC in creating host legacies (IOC 2007) merit further inquiry. Accordingly, this book sets out to answer three key questions: (1) Is the urban planning process altered due to Olympic requirements? And if so, how? (2) Consequently, what role does the IOC play in urban development and the creation of transport legacies? (3) Given the IOC’s role, how can host cities plan for valuable Olympic legacies and aspire not only to host the best Games ever, but also retain the best legacies ever? To take advantage of the opportunities mega events bring to cities, the key question for planners to answer is how cities can align the necessary transport provisions for staging a world-class event with their metropolitan vision, and hence, use the mega event as a driver towards desirable change.

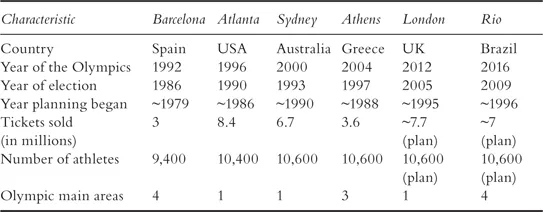

In the following chapters, I investigate the urban planning processes and the resulting legacies of four Summer Olympic host cities, Barcelona (1992), Atlanta (1996), Sydney (2000) and Athens (2004), and foreshadow the planned legacies of two future host cities, London (2012) and Rio de Janeiro (2016). Even though all case cities are intrinsically different with unique histories, economies, political institutions, urban forms and transport networks (Table 1.1), they approached the Olympic planning process with the same goal: to stage successful Games.

TABLE 1.1 Olympic host cities’ characteristics

Sources: Compiled by author. Adapted from ACOG 1994; ATHOC 2004; 2005, Bovy 2005, 2011; CMB 1986; Currie 2007; Greater London Authority 2011; House of Commons 2003; LOCOG 2005; OASA 2009; ODA 2009; ORTA 2001; Rio 2016 2009.

While the number of athletes stayed fairly constant overtime, the tickets sold (or expected to be sold) varies greatly. Planning for the Olympic Games also had different time horizons and resulted in the creation of one central or multiple Olympic main areas. Therefore, each city’s leaders, trying to use the Olympics as an opportunity for urban change, considered individual transport and urban goals in the city’s spatial context. While my case study analysis stretches roughly over two decades, focusing on the three key questions about requirements, the IOC’s role and legacies, will succinctly guide the internal structure of each chapter and the book.

Book structure

In Chapter Two, I introduce the International Olympic Committee (IOC) as a powerful stakeholder in the urban planning process. Throughout this chapter, I identify requirements the Olympics bring to bear on the transportation and venue planning process. My key argument is that the IOC, equipped with the Olympics...