- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Art in the Primary School

About this book

Art has always been an important part of the primary school experience. It is now one of the foundation subjects in the National Curriculum. In this book, John Lancaster helps teachers rise to the challenge of art for young children. He encourages thought about the purpose of art teaching, and at the same time provides a wealth of project ideas and helpful advice on how to organize art, craft and design in the primary classroom. The book, fully illustrated with charts and black and white plates, gives practical advice on how to: define suitable objectives and plan lessons so as to achieve them make the best use of natural and man-made resources within and outside the classroom present children's work effectively by display throughout the school encourage aesthetic awareness and art knowledge by a study of the historical and cultural aspects Organise and benefit from visits to local art galleries approach assessment of children's art and craft activities This is a basic philosophical and practical guide which will give confidence to new teachers and fresh ideas to their more experienced colleagues.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Art in the primary school

What do we mean by art, craft, design and appreciation?

Some educationalists look at art, craft, and design as three distinct subjects, and in the past many teachers taught ‘art’ and then they taught ‘craft’. It is questionable as to what they thought of as ‘design’—which is a fundamental component of both art and craft—although this aspect is considered today to be some kind of new subject which must be taught as a discrete discipline. In this book I intend to place these three aspects together under the umbrella of ‘art’ so that it is easier for me to write about and, I trust, easier for my readers to understand. I shall, of course, refer to all three individually from time to time, and the fourth aspect, ‘appreciation’, will also be discussed.

Let me begin by looking at ‘art’, ‘craft’, ‘design’ and ‘appreciation’ as four distinct aspects of the subject. Three of these obviously involve the direct use of materials in classroom situations where children participate actively in artistic production, i.e. in the making of art (whether this be in the form of paintings, prints, patterns, models, posters, pottery, or video films). In my opinion, the fourth aspect, appreciation, grows best from the children's experience of doing art work and therefore it, too, can be said to depend upon the manipulation of materials and the knowledge gained through artistic production. This is a disputable concept about which I shall say more shortly; some educationalists would disagree with this idea, insisting that children can be taught how to ‘appreciate’ art—whether in an historical or modern context -without actually doing it themselves. What is important, however, is that you, the teacher working in school now, will need to consider this problem and resolve it in your own way.

What do we mean by the terms art, craft, design and appreciation? Are they one and the same thing? Are they interrelated? I suggest that they need to be thought about and propose the following definitions as starting points:

- The term ‘art’ covers that area of inventiveness with art and craft materials through which self-expressed emotions, ideas and feelings resulting from the visual interpretation of environmental experiences are communicated, while depending upon acquired craftsmanship and artistry.

- Craft, on the other hand, embraces the acquirement and utilization of manual skills in the manipulation of two- and three-dimensional materials, hand-tools, and/or mechanical equipment. It provides artists, designers and craftspersons with the means of artistry, or what is known quite simply as making art.

- Artistry depends upon the imaginative or inventive use of knowledgeable and skilful making and designing, and therefore the design aspect is the knowledgeable area in which inventiveness germinates and develops into recognizable artistic form.

Teachers must recognize that these aspects are interdependent. They simply cannot exist in isolation but rely upon good hand, eye, and brain co-ordination; in other words, they spring from an harmonious relationship. Some years ago schoolchildren ‘did some art’, perhaps a drawing or a painting, and then they ‘did some craft’—perhaps making a raffia mat. If they had an interested teacher they might then do ‘some design work’—which might have consisted of making a stencil pattern on the cover of an exercise book. It is important today to ensure that they receive a much broader range of practical experiences in a curriculum which gives them a wider educational grounding.

- 4 The appreciation aspect tends to be separated from the other aspects. I cannot understand why this is so, unless it stems from teacher uncertainty, for it, too, results best from artistic practice and must be aided by empirical knowledge gained through such experience. It is the thoughtful, critical area in which children make value judgements and assessments of works of art, craft, and design in relation to both their historical and cultural context, and the meaningful place of art in the lives of people world-wide.

As I have already stated, some people—amongst them art critics— seem able to ‘appreciate’ art without having made it. I would argue that this is not really possible and that their appreciation and criticism cannot be total. Is it possible to appreciate how paint has been laid on a canvas if one has never had the experience of doing it? Can I appreciate the feelings which an astronaut has in stepping on to the moon's surface if I have never done this? I fancy not. The Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation Report, The Arts in Schools (1982), supports my view, stressing that aesthetic education is important for young children while pointing out that the arts are important in structuring cultural traditions which children with experience as creative communicators will obviously understand better and value more— of course they will, for these will be more meaningful to them.

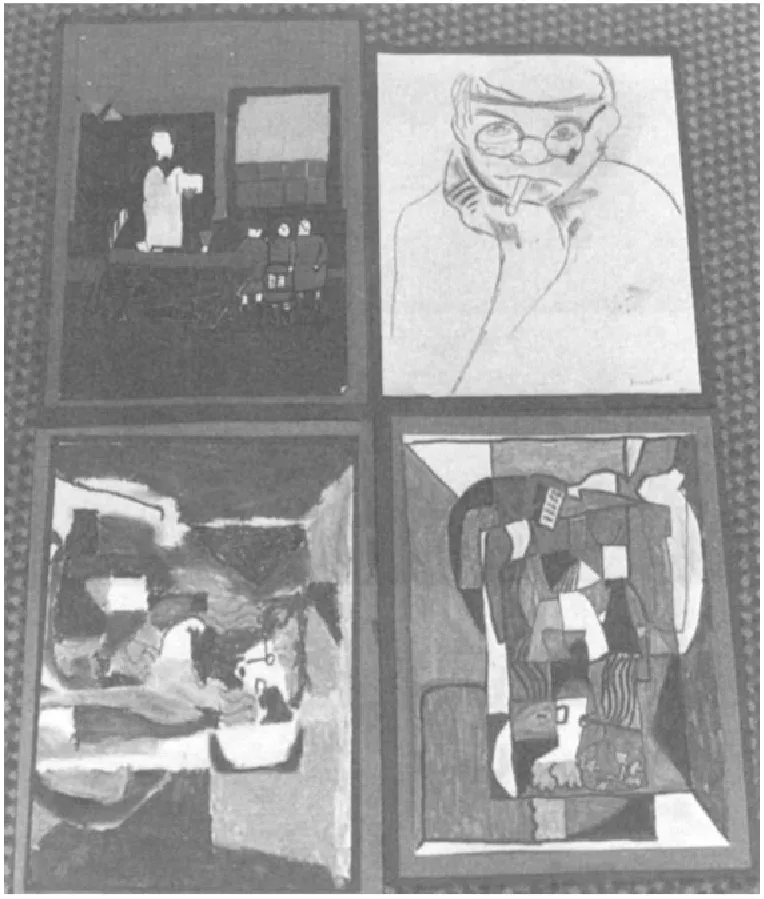

Plate 1 These freely interpreted drawings and paintings by older junior school pupils were copied from reproductions of the works of famous artists. In doing this the children learned a great deal about the artists and how they worked.

The ‘appreciative’ aspect embraces emotional, sensory response by children and the intellectualization of their inventive artistic experiences. It is an area which emphasises the appreciation of artistry, craftsmanship and qualities of design—whether in the cultural artefacts of primitive peoples (and here I include prehistoric examples as shown to us in cave art, as well as the art of native tribes in remote regions of the world today), or in ‘fitness for purpose’ of, for instance, ergonomically-designed furniture for an office, a home or a spaceship. Its real value lies in promoting critical aesthetic attitudes in children so that they acquire artistic understanding and an appreciation of qualities of beauty while, at the same time, developing sensitivity to works of art and craft and the craft skills used by creative persons.

The role of art in developing children's creativity and aestheticism

Primary teachers have the very interesting task of teaching right across the curriculum, which demands an understanding of how children learn as well as some interest in and knowledge of a variety of subject areas. Most have little knowledge and expertise in art—which embraces designing and making—for they have probably had few opportunities to engage in art activities in their teacher education courses, while earlier their academically-orientated ‘O’ and ‘A’ level studies forced many to drop art at secondary level in order they they might concentrate upon ‘meaningful’ subjects. Yet art and craft (as one subject area) embraces a wide range of practical activities in both two- and three-dimensional aspects, calling for some knowledge on the part of teachers about materials, tools, equipment, storage, the teaching of skills, artistic production, presentation, and assessment; knowledge which is best acquired through involvement and experience over a period of time working in classrooms with children.

When teaching art the teacher is really on a batsman's wicket, for children like doing it. There is a creative urge in every human being-young and old alike—for we all have a natural desire to use our hands and materials as vehicles for artistic expression. If given the right kind of opportunities even pre-school children (some may be only a few months old) will take great delight in expressing themselves with art materials. Place a sheet of paper on the kitchen floor for a three-year-old, and it will grasp a thick crayon firmly and draw linear images crisply and dynamically. Give the same child a hog hair brush and some thick paint and it will relish the experience of painting with an uninhibited confidence which is often quite remarkable to the uninitiated adult. Young children certainly have an inner urge which stimulates creativity, and when they enter school teachers must encourge their ‘originator instinct’, as Martin Buber (1978) described it, by giving them opportunities to be young artists, craftspersons and designers. This will help them to develop stronger aesthetic sensibilities and an understanding of works of an artistic nature—whether these are of today or of the past—and to train them to develop manipulative skills of value to them in varying curricular aspects and, later, as adults and even as home-owners, in which capacity they will need to be selective in choosing furniture and furnishings, in decorating and in garden planning.

Plate 2 A young, pre-school child will often draw in a vigorous, uninhibited way with pencils or large crayons. This girl is exploring simple ‘mark-making’, which increases her experience of graphic images and concepts.

Art, Craft and Design in the Primary School (Lancaster, ed. 1987) stated some basic teaching guidelines for primary teachers. It stressed the sensible planning of art, craft and design curricular and the use of well-prepared and relevant sequentially-structured programmes, and therefore encouraged trainee-teachers, and teachers in schools, to provide for their pupils a realistically-conceived and solid aesthetic education within the broader context of the primary curriculum. Teaching aims and philosophies were discussed, as were ideas on curriculum strategies and support sources, and I shall obviously refer to it from time-to-time.

Basic subjects such as English and mathematics tend to have prime timetable time. I sometimes wonder why. Indeed, I remember studying these and science subjects at school, with art and music thrown in as space-filling activities to which my academically-orientated teachers attached little if any value. Yet I cannot honestly think that the mathematics which I was taught has helped me, since I am hopeless at organizing the household accounts and fail to understand investment procedures and banking—aspects that have real significance to everyday living. School calculations regarding the simultaneous filling and emptying of a bath simply left me bewildered. Who would want to do such a silly thing in the first place? The logic of the event escaped my comprehension and therefore I saw no reason to attempt to understand the problem, let alone work it out. Trigonometry, too, failed to appeal to my more artistically inclined way of thinking, while the squaring of algebraic numbers left me unmoved. I have also had to struggle to learn how to write with a certain degree of fluency, for my School Certificate (‘O’ level equivalent) course did not give me much direction. When I was in the army on National Service, however, I was responsible for arranging pre-demobilization courses in commerce and industry for officers and other ranks and the letters I composed, and often typed myself, were meaningful and important for the jobs and lives of men and their families. Perhaps this is the difference. When something is ‘meaningful’ we recognize this and attempt to do it well. If this is so, then what happens in the classroom must be meaningful and children must feel that it is. Art, for me, was different. I liked it and I liked my art master. I went to study it further at art college, very much against parental wishes and teacher advice, and it became a way of life. It was meaningful, it was enjoyable and it was important. I didn't question why it was so, I simply accepted it as such.

Art really is most important in the lives of every individual. We need some artistic and designing expertise and understanding so that we are able to select with confidence well-considered wardrobes of clothes, colour schemes, furniture, furnishings—or simply aesthetically pleasing greeting cards—throughout our lives. We see the products of art every day in advertising, television, magazines, in our streets where street signs and shop window displays catch our attention, in the design of buildings, shopping precincts and parks, as well as in countless other objects which abound in the environment. Our world today is extremely vision-conscious and visual images and aesthetics play powerful roles while exerting a powerful influence on almost everything in it.

If primary teachers intend to provide a well-planned and balanced education for their pupils so that they can go on to enjoy a full and aesthetically-rewarding life then art education must have a valuable place in this. Children are the home-makers, parents and therefore the adult consumers of tomorrow. They are our future citizens and future politicians who will be responsible for environmental projects involving art and design concepts. They will be involved as active decision-makers, possibly tackling large development projects concerned with community life and on quite a vast scale and costing vast amounts of public money. If they have had a sound education in art and design it stands to reason that they will be much more conscious of the value of aesthetics in what they do and will fight for well-considered visual quality in what is conceived. They need, then, to experience and understand the rudiments of aesthetics and design—colour, pattern line, tone, form, structure, arrangement, which are the basic elements of a Visual grammar’. These elements are the building bricks of art, and in experiencing and using them in making art children will expand their aesthetic understanding not only for their own fulfilment but also for the future good of society. Their lives will be enriched, for they will obtain real pleasure and a sense of personal achievement through producing objects of beauty which others can also enjoy. By developing their pupils’ aestheticism, teachers will enable them to create aesthetically-pleasing environments and art objects. This will also give them an increased understanding of the art which others produce or have produced.

The purpose of art in primary education

I have established that art provides children with opportunities to experience ‘making’ and ‘designing’, practical experiences in which both inventiveness and direct observational copying are encouraged.

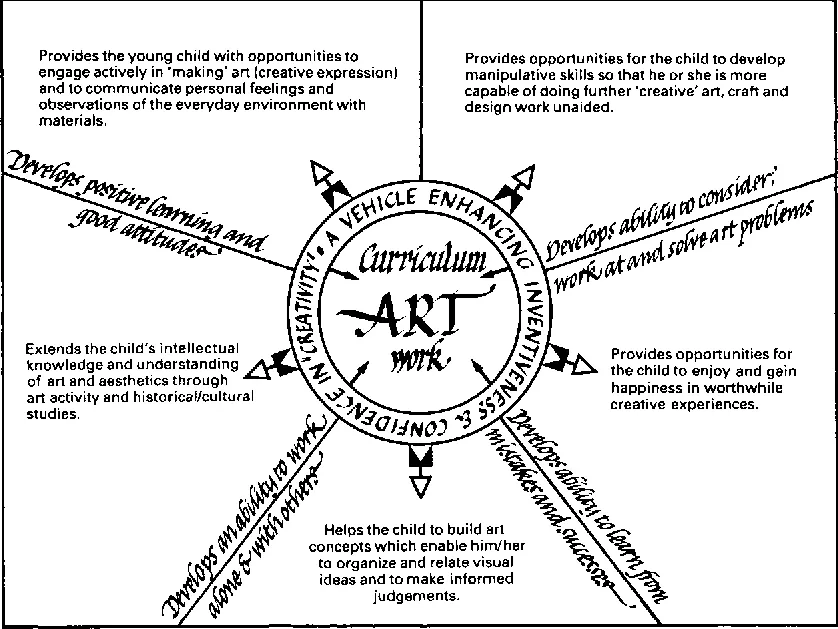

Figure 1 Chart showing how curriculum art work increases a child's aesthetic understanding and capabilities. (Inspired by HMI criteria, see DES 1987b: 2.)

It gives many less academically inclined pupils the chance to experience some success. Teachers recognize, of course, that success is very important if learning is to flourish and progress, and if children with learning difficulties in the so-called core subjects can be stimulated by their abilities in doing art work, then this area of curriculum studies can be an invaluable key to the unlocking of other interests and the promoting of learning potential which might otherwise remain stifled or unrealized. Art also offers children with a more academic bent opportunities to enhance their practical knowledge, giving them different intellectual channels of experience which are challenging and rewarding.

Art in the classroom is sometimes misinterpreted as a ‘play’ activity, but teachers recognize that in the child's terms ‘play’ is synonymous with ‘work’. It involves children in intense concentration and effort, and because the very act of ‘playing’ is an enjoyable one, they enjoy this effort. It is an activity area which can be a very necessary foil to the more constricting curricular aspects while offering tremendous scope for co-operative working in both large and small groups—in teamwork, where respect for others is engendered and the co-operative sharing of ideas and skills is participated in freely. This is where leadership potential changes, often resulting in the less able children blossoming because their more practically-orientated expertise is required in the production and subsequent realization of intellectual concepts in practical and material terms. In other words, they are given a chance to be successful! It would be wrong to offer the argument that non-academic pupils are skilled practitioners and, conversely, that academic children are not, however. Indeed, this would be a false assumption for time and time again throughout history important artists and craftspeople have been seen to be endowed with a highly-developed intellectualism which complemented their inventive and making skills, raising their artistic products to the highest, most expressive levels.

The visual arts, like those of music, dance, and theatre, are good for the soul and primary school children are fortunate in being able to get right into the essence of art in their humble classrooms. They actually do some art. A few of them might then go on to do a little in their secondary education but how many will ever have the opportunity to be active makers of art again? Will they ever again use art materials? Is the art work which they do at primary school the only such artistic experience they are likely to have? These are questions for primary teachers to bear in mind. They must also ensure that the art which their pupils do is purposeful while also helping to provide a more complete education for them.

On the more mundane side, art is also a ‘servicing agency’ and it must not be treated as some form of precious aestheticism. It has always had a servicing function in society—whether adult-based or as an aspect of work in schools—and we should continue to see this as an important part of its operation. For instance, drawing and picture-making skills developed in this area will then be applied with more confidence in mathematical and scientific subjects; in the study of costume in history; in the visual presentation of apparatus; in the illustration of poems and passages of prose; and in the production of maps. Puppet theatres will be enhanced by well-conceived and delightfully-made puppets, with colourful and correctly-attributed costumes; by painted backcloths and printed curtains; by painted lettering; and even by carefully-controlled lighting effects. Thoughtful, caring teachers will consider the ramifications carefully and thoroughly. They will plan their general curriculum to be all-embracing and will realize that art must be used to enhance learning potential and to increase excellence across the primary curriculum.

In the early childhood years, particularly those we associate with t...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Art In The Primary School

- Figures

- Plates

- Series Editor's Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1: Art in the primary school

- 2: The framework for planning art activities

- 3: Planning what to teach

- 4: Organizing art within the primary curriculum

- 5: Art in school

- 6: Art outside the classroom

- 7: Some ideas

- 8: Project work based upon heraldry

- 9: Two case studies

- Brief glossary of terms

- Bibliography

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Art in the Primary School by John Lancaster in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Pedagogía & Educación general. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.