This is a test

- 168 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Geopolitics identifies and scrutinizes the central features of geopolitics from the sixteenth century to the present. The book focuses on five key concepts of the modern geopolitical imagination:

* Visualising the world as a whole

* The definition of geographical areas as 'advanced' or 'primitive'

* The notion of the state being the highest form of political organization

* The pursuit of primacy by competing states

* The necessity for hierarchy.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Geopolitics by John Agnew in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

1

Introduction

In the aftermath of the attacks on the World Trade Center in New York and the Pentagon (US Defense Department) outside Washington, DC, on 11 September 2001, US President George W. Bush declared war on ‘terrorism’. This, it has become clear, involves much more than simply going after those who perpetrated the attacks – the so-called al-Qaeda network of Islamic terrorists led by the Saudi Arabian millionaire Osama bin Laden. The result has been nothing less than a total reorganization of world politics, with the US government claiming the right to intervene militarily wherever and whenever it wants, initially in Iraq but without precisely defined geographical limits. Rooting out terrorism all over the world has now replaced older themes in the US foreign policy lexicon, working backwards from most to least recent, of ‘containing Communism’ (in the former Soviet Union and its sphere of influence), creating ‘collective security’ after the First World War, or helping to maintain the balance of power between the European Great Powers in the late nineteenth century. The US government is now able to do more or less as it pleases (at least militarily) because it has become the single superpower. Of course, it also sustained the attacks on its soil because of its global geopolitical centrality and support for governments – particularly those of Israel and Saudi Arabia – that excite much hostility from Muslim extremists.

What is new after 11 September 2001 is that the world has never before had just one major power combined with a violent opposition from a shadowy network without a single state to its name (although it came close to having one in Taliban-dominated Afghanistan between 1996 and 2001). What is more familiar, however, is that the US government and its new adversaries are participants in a global ‘game’ for political control and influence that has dire consequences for the world as a whole. The game goes back to the creation of modern world politics beginning in the sixteenth century but getting into full swing only in the nineteenth century. It is the fruit of a modern geopolitical imagination that encompasses and directs the theories and practices of world politics. This geopolitical imagination has long framed world politics in terms of an overarching global context in which states vie for power outside their boundaries, gain control (formally and informally) over less modern regions (and their resources) and overtake other major states in a worldwide pursuit of global primacy. It is the combination of all these features that makes the geopolitical imagination a peculiarly modern one.

The period since the ending of the Cold War in 1989–91 has seen a number of other dramatic changes that, along with worldwide terrorist networks, might seem to challenge the continuing utility of the modern geopolitical imagination as a singular guide to practice in world politics. These would include the deepening of the European Union with the creation of the new currency, the euro, thus giving rise to a new form of polity that is neither a gigantic territorial state nor a simple common market; the collapse or decreased power of central government institutions in many states across the world – from Colombia in South America to Somalia in Africa and Afghanistan in Asia; the threat of national economic bankruptcy in the case of states such as Argentina, Brazil and Turkey; the tremendous growth of China as an export-based manufacturing economy supplying seemingly endless amounts of consumer goods to deindustrializing economies such as the United States; and the inability of the main parties to many nationalist conflicts, such as that between Israel and Palestine, to reach agreements over their mutual boundaries because each claims much the same territory as the other. The state-based world in which the modern geopolitical imagination has developed and to which it applies might seem to be in serious disarray.

The Modern Geopolitical Imagination

The purpose of this book, however, is to identify the major elements of this long-dominant approach to world politics – the modern geopolitical imagination – and to show their historical–geographical specificity in the European and, later, American encounters with the world. In other words, the aim of the book is to show how the dominant geopolitical imagination arose from European–American experience but was then projected on to the rest of the world and into the future in the theory and practice of world politics. Beginning in the 1980s, as the Cold War ended, globalization began to offer the possibility of a world structured in a very different way. For example, as the Berlin Wall fell in November 1989, so also did the geopolitical template of Soviet East versus American West that had underwritten world politics for the previous forty years. National economic well-being increasingly seems to depend on advantageous connections to a world economy no longer totally dominated by the policies of dominant states. Even if the reactions by governments to any number of recent events – from the terror attacks of 11 September (and later ones such as that in Bali, Indonesia, on 12 October 2002) leading to a focus on Afghanistan and Iraq more than the terrorists themselves, to the continuing dispute between North Korea, on the one side, and Japan and the United States, on the other, and the bloody conflict between Russia and Chechen separatists as Russia reasserts itself as a Great Power defending its ‘territorial integrity’ – might suggest that the modern geopolitical imagination still has plenty of political mileage left in it yet, there are nevertheless trends whose interpretation points in a different direction.

More particularly, a number of crucial ‘certainties’ from as recently as fifteen years ago – about, for example, fixed and unquestioned political boundaries between states, the division of the world into mutually hostile armed camps on the basis of political ideology, the centrality of states to world politics, and the primacy of fixed national identities in political psychology – have either disappeared or are seriously in question. The end of the Cold War, the growing importance of trading blocs such as the European Union, and the proliferation of ethnic and regionalist movements within established states have served to undermine much of the conventional wisdom at the heart of the modern geopolitical imagination. Perhaps it is not entirely surprising, therefore, that there is now increased attention paid to the ways in which academics and political leaders have understood and practised world politics. In times of flux, conventional wisdom is more open to scrutiny.

This book focuses on the angle of vision provided to understanding world politics by the role of dominant geopolitical understandings. The phrase ‘world politics’ itself conveys a sense of a geographical scale beyond that of any particular state or a locality in which states and other actors come together to engage in a number of activities (diplomacy, military action, aid, fiscal and monetary activities, legal regulation, charitable acts, etc.) that are intended to influence others and extend the power (political, economic and moral) of the particular actors who engage in them. But the activities also rest on more specific geographical assumptions about where best to act and why this makes sense. The world is actively spatialized, divided up, labelled, sorted out into a hierarchy of places of greater or lesser ‘importance’ by political geographers, other academics and political leaders. This process provides the geographical framing within which political elites and mass publics act in the world in pursuit of their own identities and interests.

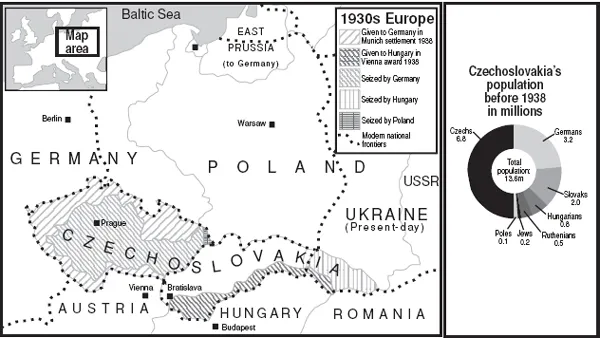

Figure 1.1 A spectre haunts Central Europe, the history of its boundaries.

Source: Author

A couple of examples can serve to illustrate the ways in which the geographical framing at the heart of the modern geopolitical imagination takes place. Central Europe, for example, has actively figured in US, German, Soviet and other Great Power foreign policies for many years. It was the primary focus of Nazi German territorial expansion before and during the Second World War. Czechoslovakia was portrayed on Nazi geopolitical maps in the late 1920s and in the 1930s as a ‘dagger’ pointing at the heart of German territory. During the Cold War it was the main arena of ‘geopolitical tension’ between the US and Soviet ‘sides’. Today it has re-entered world politics largely in relation to the geographical expansion of the European Union. The region’s past roles, however, have not entirely faded. Indeed, the redrawing of international boundaries, loss of life, and large-scale population movements at the end of the Second World War still haunt Central Europe (Figure 1.1). In the summer of 2002, just as the European Union was discussing potential membership by various central European states, the rediscovery of the ‘Beneš decrees’ issued by the Czechoslovak government in 1945 (the legal basis for the eviction of the Sudeten Germans from Czechoslovakia) suddenly revived debate in Germany and throughout the region over what had become a ‘dead’ issue during the Cold War: the boundaries between the states of the region and the compensation (including restoration of property) due those displaced. Central Europe, therefore, has not entirely lost its role as a geopolitical marchland between West and East even as the historical context has obviously changed.

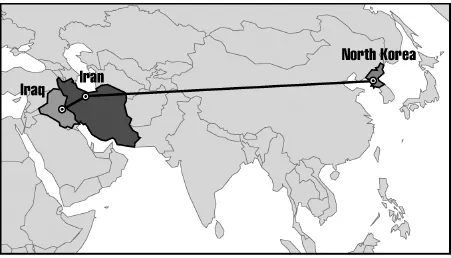

For a second example, in his State of the Union address in January 2002, President George W. Bush not only declared war on terrorism but also identified what he called an ‘axis of evil’ in world politics, with the three states of Iraq, Iran and North Korea as its geopolitical anchors (Figure 1.2). Formerly referred to, with a list of others, as ‘rogue states’, these three were singled out because of (i) their quest to possess ‘weapons of mass destruction’ – biological, chemical and nuclear; (ii) their hostility to the United States in particular and the contemporary global distribution of power in general; and (iii) their alleged support for terrorist groups and other rogue states. That Pakistan and Saudi Arabia, for example, might equally qualify for membership in the ‘axis’ because of the former’s supply of bomb-making equipment to North Korea and its own pursuit of weapons of mass destruction and the latter because of its long-term support of fundamentalist Islam and financial support for bin Laden’s al-Qaeda terrorists underscores the importance of criterion (ii) relative to the others. The image of an axis of states challenging the United States is more important than empirical accuracy in whether or not they are the most important developers of weapons of mass destruction or fomenters of terrorism. The image is that of an ‘axis’ or real connection between them, even though it is not clear what each shares in common beyond the three criteria listed above, and involves a clear analogy back to the Second World War when Germany, Italy and Japan (which really were allies) formed the so-called Axis Powers. President Bush was thus attempting to give a clear geopolitical structure to the threat faced by the United States (and the current world order) and recall a powerful threat from the past in support of his case. Later in 2002, President Bush invoked the ‘axis’ to justify a new foreign policy doctrine for the United States based on the possibility of conducting preventive wars against states that might eventually pose a threat to the United States (including the ‘threat’ to the world oil supply from countries such as Iraq in which the oil industry is state owned and not dominated by US companies) even if such a threat is currently not imminent.

Figure 1.2 President George W. Bush’s ‘axis of evil’.

Source: Author

Indeed, one way of thinking about the geographical framing of foreign policies is to recall the foreign policy ‘doctrines’ enunciated by various US presidents down the years, from President Monroe in 1823 through President Truman in 1947 to President G. W. Bush in 2002. The Monroe doctrine initially involved three geopolitical imperatives relating to US foreign policy: the Americas were closed to further European colonization; the United States must avoid involvement in wars in Europe; and, in particular, that the US government would regard the effort by any European power to expand its empire into the western hemisphere as a threat to the United States itself. Eventually, for example during the Johnson and Reagan presidencies, this doctrine was invoked to justify US military intervention in various parts of Latin America – something remarkable by its absence from the original statement of the doctrine. In its turn, the Truman doctrine of 1947 helped to set the scene for the Cold War by challenging the Soviet attempt at violating the boundaries between the US and Soviet spheres of influence established just two years previously at the Yalta Conference by attempts at using surrogate forces to undermine governments allied with the United States, initially in Greece and Turkey but later more generally. The Bush doctrine of 2002, enunciated by President Bush in a speech at the US Military Academy at West Point, New York, is also explicitly interventionist, only the claim of the right to intervene now includes the explicit right to preventive US military intervention when a specific state is declared to threaten or pose an immediate danger to the US ‘national interest’ but has not yet mounted any kind of military strike.

The term ‘geopolitics’ has long been used to refer to the study of the geographical representations, rhetoric and practices that underpin world politics. The word has in fact undergone something of a revival in recent years. The term is now used freely to refer to such phenomena as international boundary disputes, the structure of global finance, and geographical patterns of election results. One expropriation of the term ascribes to it a more specific meaning: examination of the geographical assumptions, designations and understandings that enter into the making of world politics. Some recent work in political geography has tried to show the usefulness of adopting this definition of the term. In using this definition here, I attempt to survey how the discovery and incorporation of the world as a single unit and the development of the territorial state as a political ideal came together to create the context for modern world politics. Studying geopolitics in this sense, or geo-politics, so as to distinguish it from what is being described, means trying to understand how it came about that one state’s prospects in relation to others’ were seen in relation to global conditions that were viewed as setting limits and defining possibilities for a state’s success in the global arena. The use of visual language is deliberate. World politics was invented only when it became possible to see the world (in the imagination) as a whole and pursue goals in relation to that geographical scale.

According to the history of the word, geopolitics began in 1899 when the word was first coined by the Swedish political scientist Rudolf Kjellén. The coining of the word meant that thinking globally on behalf of particular states was explicitly connected by formal geopolitical reasoning to their potential for acting globally. Ways of thinking and acting geographically implicit in the phrase ‘world politics’ had begun much earlier, however, when the intellectuals of statecraft of the European states (leaders, military strategists, political theorists) pursuing their ‘interests’ had to consider their strategies in terms of global conditions revealed to them by the European encounter with the rest of the world. Indeed, as Chapter 2 details, Renaissance-era Europeans drew upon older sources (particularly the cosmography of Ptolemy) to direct their understanding of the world. What was new, however, was that the world they encountered corresponded increasingly to the Earth as a whole rather than to the geographically limited worlds known to the ancients. The onset of the capitalist world economy and the growth of the European territorial state gave rise to a novel set of understandings about the partitioning of terrestrial space. The layering of global space from the world scale downwards created a hierarchy of geographical scales through which political–economic reality has been seen; in order of importance, the four have been the global (the scale of the world as a whole), the international (the scale of the relations between states), the domestic/national (the scale of individual states) and the regional (the scale of the parts of the state). Problems and policies have been defined in terms of the geographical scales (either domestic/national or international/foreign) at which they are seen as operating within a global context. Consequently, world politics is understood as working from the global scale down. It is at the global scale, therefore, that the term ‘geopolitics’ is usually applied. Yet it rests on assumptions about the relative importance of the various geographical scales to life on the planet that are already in place. The global and the national are privileged largely to the exclusion of the others. But naming such assumptions geopolitics and creating models that claim a superior grasp of geopolitical realities came much later than the onset of the geopolitical representations and practices themselves. The purpose of this book is to identify and critically examine the central features of the geopolitical imagination that arose in Europe, beginning in the fifteenth century, and that later became the stock in trade both of conceptions of world politics and of the practices of foreign policy.

The modern geopolitical imagination is a system of visualizing the world with deep historic roots in the European encounter with the world as a whole. It is a constructed view of the world, not a simple spontaneous vision that arises from simply looking out at the world with ‘common sense’. As a system of thought and practice, the modern geopolitical imagination has not existed and does not exist in a material vacuum. It first developed in a Europe coming to terms with both a new global role and the disintegration of the religious-based image of universal order formerly dominant among its intellectuals and leaders. An insistence on taking charge of the world is a key feature of European modernity. Its realization has changed significantly over time as the material context (dominant technologies, modes of economic organization, scope of state organization, capacity for violence) has changed (see Agnew and Corbridge 1995). This is why after identifying and discussing its four foundations I turn to its historically specific operation over the course of the past two hundred years. This historical geopolitics, focused on practical geopolitical reasoning, needs to be distinguished from what is sometimes called critical geopolitics, taken either with exposing the hollow claims of particular geopolitical writers to having found the ‘truth’ in world politics or with identifying the representational basis to particular foreign policies.

Several other distinctions are also worth making, to clarify the purpose of the book. This is not a restatement or elaboration of the geopolitics associated with the inventors of the term and its applications: Rudolf Kjellén, Friedrich Ratzel, Halford Mackinder, etc. Neither is it an argument in support of that tired, cynical, aristocratic world-view popular with political realists in establishment universities and think tanks (for recent good examples of the genre, see, for example, Mearsheimer 2001; and Haslam 2002) that...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: Visualizing global space

- Chapter 3: Turning time into space

- Chapter 4: A world of territorial states

- Chapter 5: Pursuing primacy

- Chapter 6: The three ages of geopolitics

- Chapter 7: A new age of ‘global’ geopolitics?

- Chapter 8: Conclusion

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index