![]()

An introduction to urban ecology and urban ecosystems

1.1 About this book

The purpose of this book is to provide a broad overview of urban ecology and urban ecosystems for students, researchers and practitioners. Research into urban ecology has blossomed in the last two decades, bringing with it both increased interest and understanding of urban ecosystems, ecological processes and biodiversity. Although this text cannot provide exhaustive coverage of all aspects of what is a broad and interdisciplinary area of study, it will equip the reader with a sound understanding of the main concepts and topics relevant to the field, and act as a primer for further exploration of the literature.

The focus of the text is on the ‘urban region’ (defined and discussed in more detail below), and includes many forms of urban ecosystems. As Pickett et al. (2001) note in their key paper on linking ecological, physical, and socio-economic components within urban areas, an ecological understanding of an urban region must include the less densely populated suburbs, satellite towns and villages, and rural/urban gradients because species, materials and energy flow between these different components. This book therefore endeavours to cover a wide spectrum of urban environments to fully equip the reader with a suitably broad understanding.

This text does maintain something of a focus on heavily urbanised areas, however, as such ecosystems are the most extreme modifications that humans have made to the natural environment, and represent perhaps the most interesting systems for studying the effects that urbanisation and human activity can have on ecological patterns and processes. They are also the most exciting opportunities we have for environmental improvements and monitoring future broad-scale ecological changes. Urban regions are, from an ecological point of view, huge and prolonged experiments that have changed (to a greater or lesser extent) the characteristics found in natural ecosystems so that something new, strange and wonderful has emerged. This book aims to summarise and elaborate on some of these aspects of urban regions.

The book is divided into nine chapters, as follows:

- Chapter 1 provides an overview of what urban ecology is, what urban ecosystems are, and how some key urban terms have been defined. It also briefly summarises the history of urbanisation and reflects on why urban ecosystems are important or interesting ecologically.

- Chapter 2 considers the form, structure and dynamics of urban environments at both regional and landscape scales, highlighting some ways in which spatial organisation and temporal dynamics may relate to ecological patterns and processes. It also considers the three-dimensional structure of urban environments. These topics are important for developing a full understanding of the biophysical template urban areas represent, which both shapes and is shaped by ecological processes.

- Chapter 3 gives a broad overview of the urban region as an ecosystem, highlighting some of the key characteristics associated with urban environments.

- Chapter 4 examines urban ecosystems found within urban regions, focusing on those that may be classified as ‘green space’. This includes parks and recreational spaces, gardens, lawns, allotments, brownfield and wasteland sites, remnant woodland, and urban rivers and lakes.

- Chapter 5 looks at urban ecosystems found within urban regions that are formed in large part from the built environment, including built surfaces, living roofs and walls, terrestrial and aquatic infrastructure such as roads, pavements, railways, underground rapid transit systems, sewerage systems and canals, and infrastructural trees.

- Chapter 6 covers urban species, discussing common trends observed in the types of species and assemblages found in urban ecosystems, including seral changes and ways in which species respond to urban environments.

- Chapter 7 considers nature conservation in urban regions, looking at the preservation and restoration of species and green space within an urban context, as well as the possibilities represented by urban reconciliation ecology. It also reflects on conservation governance and the growing role of citizen science.

- Chapter 8 briefly examines how ecology has been and continues to be incorporated into urban planning and design, looking at ecologically sensitive urbanisation, the planning and design of green space and green networks, and examples of ecological and environmental engineering in urban regions.

- Chapter 9 summarises some likely future trends relating to urban ecosystems, including urban growth, biodiversity, sustainability, and planning, and finally draws out some key areas for future research in urban ecology.

Each chapter incorporates a brief summary and some open questions that may be used as starting points for wider class discussions or further individual investigation.

1.2 Urban ecology: what it is and is not

Ecology as a discipline developed from a background of natural history in the nineteenth century; the term (Oekologie) was first used by Haeckel (1866), though the formalisation of the scientific discipline from the more descriptive precursor of natural history really occurred in the early twentieth century with the work of ecologists such as Frederic Clements, Henry Gleason and Arthur Tansley. ‘Ecology’ may refer to the interactions and relationships between organisms and the abiotic environment, or the science of studying these. It is usually, as in the case of urban ecology, further refined within the context of a particular ecosystem or environment (tropical ecology, desert ecology), groups of organisms or their defining traits (mammal ecology, invasive species ecology) or space or timescale (landscape ecology, palaeoecology). Importantly, ecology must incorporate the living world (and in particular the nonhuman living world). In many ways it is the oldest science, as humans have always had cause to investigate interactions between animals, plants and their environment, to make them successful hunter-gatherers and eventually agrarian species. The formalisation of the discipline has been surprisingly recent, but the discipline and its various subdisciplines are now major parts of the scientific canon.

The discipline of urban ecology (following the definition of ecology outlined above) has emerged relatively recently. The term ‘urban ecology’ was originally (in the early part of the twentieth century) used by human geographers and sociologists who applied ecological terms and concepts to explain human influences on spatial patterns and processes within cities (Braun, 2005). This was in essence the ‘human ecology’ of urban regions rather than urban ecology as we know it now; the environment and ‘nature’ of, and within, urban regions was considered in relation to human activities and social patterns, but it was not a focus of the discipline. Of course, the sorts of scholarly activities that would eventually feed into the discipline of urban ecology that is the focus of this book have been occurring for centuries; studies (mainly botanical) of both spontaneous and cultivated urban species and assemblages (particularly wall and garden flora), have been recorded in some urban environments since the 1600s (Sukopp, 2002), for example. The ‘new’ urban ecology, incorporating urban areas more holistically and within ‘ecosystem’ concepts, did not really develop until the 1970s.

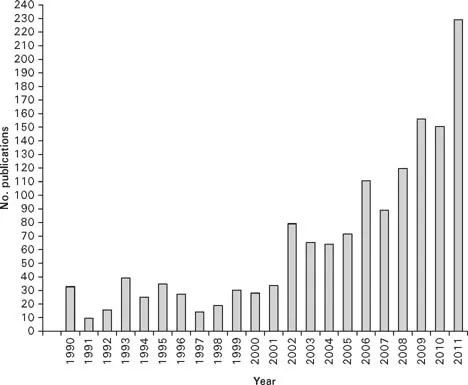

After this point, there is an increase in studies that focus more specifically on the ecology of urban areas (and a concomitant decline in the ‘human’ urban ecology) in literature databases such as ISI's Web of Knowledge (Figure 1.1). These early studies were mainly case studies or surveys, but were paving the way for more considered and holistic investigations. Urban ecology remains something of a minority discipline but an important one, and the questions that urban ecologists seek to answer are crucial to societies around the world. The rise in urban environments as a focus for both theoretical and applied investigation can be seen in, for example, the establishment of The United Nations Human Settlement Programme in 1978, which is specifically focused on urban regions; the establishment of academic journals such as Landscape and Urban Planning (1974) and Urban Ecosystems (1997); the emergence of university and research centres focusing on urban environments; and, at a more local scale the establishment of organisations like ‘Urban Ecology’ in Washington in 1975 and the ‘Trust for Urban Ecology’ in London in 1976. The science of ecology is an important aspect of all of these urban endeavours. Importantly, urban ecologists do not seek solely to apply ecological theory to an understanding of urban environments, but also to use urban environments to develop an understanding of fundamental ecological theory.

1.3 What are urban ecosystems?

The term ‘ecosystem’ is used in a very broad way to refer to spatially defined areas of the natural environment. The breadth of interpretation of this term can result in some confusion. When conceptualising an urban region for example, is the entire region the ecosystem, or is it a park within the region, or a tree within the park? The simple

Figure 1.1 Number of papers published each year found using a search of ‘urban ecosystem*’ or ‘urban ecology’ in ISI's Web of Knowledge, published between 1990 and 2011. A total of 1496 papers were found using the search.

answer is that they may all be considered ecosystems. Usually, ecosystems are broadly defined as ‘a biotic community or assemblage and its associated physical environment in a specific place’ (Pickett and Cadenasso, 2002, p. 2; see this paper for an elegant discussion of the ecosystem concept). As Pickett and Cadenasso (2002) note, this definition (a refinement of Tansley's (1935) original and enduring definition) is scale independent. This means that a rotting orange on the ground may be considered as much an ecosystem as a river or patch of woodland. However, broad spatial scales are usually the focus for ecosystem science. Sometimes, a fine-scale ecosystem is termed a ‘biotope’. Use of this term usually assumes homogeneity of environment and the presence of a particular ecological community, and thus does not often reflect the heterogeneity of conditions typically found within ecosystems. Consequently, we use the term ‘ecosystem’ across all spatial scales in this book.

Essentially, ecosystems are spatially nested and are defined relative to the specific ecological patterns or processes that are being considered (Rebele, 1994; Pickett et al., 2001). Urban ecosystems include the habitats that make up urban areas, such as buildings, walls, roads, parks, gardens, rivers, canals, and so on, the species that live in them, and the assemblages that species form.

We use the term ‘assemblage’ rather than ‘community’ in this text to designate two or more populations of species coexisting within a defined area (i.e. a discrete spatial unit), because of the potential conflation with the use of ‘community’ as the formal classification of particular species associations, such as a typical old-growth woodland community for a given biogeographical region. Although urban ‘communities’ have been explored and classified (see, e.g. Rodwell et al., 2000), given the wide range of species associations found in urban environments, we find the term generally unhelpful and so avoid it here.

1.4 Defining ‘urban’

‘Urban’ can be a difficult term to pin down, despite the way in which it is defined and used having significant implications for urban ecology. In part, this is because the term seems intuitive – most people when asked would be able to give an indication of what ‘urban’ is with some confidence, and at a superficial level drawing a distinction between ‘urban’ and ‘rural’ (for example) seems straightforward. But what is ‘urban’, technically? Definitions of urban areas generally vary b...