![]()

Chapter 1

Overview

Introduction

In June 1993, French Interior Minister Charles Pasqua announced that one of the prime objectives of the centre-right government which had just taken office was 'zero immigration' (Le Monde, 2 June 1993). Although Pasqua later qualified this statement, saying his objective was 'zero illegal immigration' (Le Monde, 8 June 1993), his remarks were deeply symbolic of the acute sensitivity attaching to the field of immigration in French public life. Far from being an overstatement, accidentally slipping beyond the narrow target of illegal migratory inflows, Pasqua's comments carried at a subliminal level a much wider resonance. In its everyday usage in France, the word 'immigration' has come to denote not simply the process of movement from one country to another, but everything associated with the permanent settlement of people of foreign origin within the receiving society (Tribalat 1993: 1911). Understood thus, 'zero immigration' is an impossible but hugely appealing objective in the eyes of many ordinary French men and women, for it carries the promise of somehow ridding the country of all the problems linked in the public mind with people of immigrant origin. In a word, it encapsulates the notion that immigrants and their descendants are fundamentally out of place in French society.

The use of the word 'immigration' to encompass what are in many respects post-migratory processes is itself symptomatic of the difficulties experienced by the French in coming to terms - both literally and ontologically - with the settlement of people of immigrant origin. In the English-speaking world, such people are commonly referred to as 'ethnic minorities' or 'minority ethnic groups', and a large part of what the French call 'immigration' is commonly known as 'race relations'. In France, such terms are taboo (Lloyd 1991; Rudder and Goodwin 1993) except among a small but growing number of academics, particularly in urban sociology and anthropology, who, inspired in many cases by the Chicago school of sociology (which pioneered the study of relations between blacks and whites in the US), are adapting the Anglo-American problematics of 'race', and more particularly 'ethnic relations', to their own field of study (Rudder 1990; Battegay 1992).

A key reason for the general rejection of these terms in France lies in the fear of giving even verbal recognition to the settlement of people seen as enduringly different from the indigenous majority. Fearful that the use of such terms might encourage the entrenchment of ethnic differentiation within French society, Schnapper (1990: 88-92), for example, argues that the notion of 'ethnic groups' is an unacceptable Americanism. Like most of France's intellectual and political elite, she prefers to speak of 'integration', a term which in recent years has been officially adopted by the state as a means of designating the incorporation within French society of people who originate outside it. As such, the notion of 'integration' has become the functional equivalent in France of 'race' or 'ethnic relations' in Britain or the US. Whereas the concept of 'race relations' appears to imply the recognition of permanently distinct groups, 'integration' is predicated on the assumption that social differentiation is or should be in the process of being reduced (Weil and Crowley 1994: 113-20). Thus even when the social heterogeneity resulting from immigration is implicitly recognized, as in the discourse of integration, the terms of that recognition presuppose its actual or future effacement.

Two state-of-the-art surveys of research in this field were published in France in 1989. The central term in the title of both (Dubet 1989; Babylone 1989) is 'immigration(s)', yet the analyses themselves focus not on population movements but on the social processes consequent upon the permanent settlement of immigrants. The pivotal term which informs the whole of Dubet's analysis is in fact 'integration'. In surveying scholarly and government research, Dubet's primary concern is to evaluate the extent to which it indicates that immigrants and their descendants are being effectively 'integrated' into French society (Dubet 1989: 5). If the title of his survey reflects the generic sweep of the semantic field now covered by French usage of the word 'immigration', the centrality of 'integration' in the main substance of his analysis exemplifies the conceptual framework within which the social consequences of immigration are most commonly articulated by academics as well as by policy-makers in France.

These conceptual considerations are important because they shape not only the terms in which the policy debate over 'immigration' takes place but also the forms in which knowledge itself is constructed. Academics often rely for much of their data on information collected by state agencies such as census authorities. In countries like Britain and the US, it is standard practice to categorize the population into groups defined by racial or ethnic origins. Census and other data collected in this way are used to pinpoint problems requiring public intervention and to monitor the effects of such initiatives. In France, the state refuses to collect nationwide information of this kind and, through its data protection laws, makes it difficult for others to do so.1

France does publish statistics on what are known in migration studies as population flows (i.e. the number of people entering, and to a lesser extent those leaving, the country over a given period of time), but only fragmentary data are available on migration stocks (i.e. people born outside France and now resident there), and still less information is compiled on their descendants. Deficiencies in records of immigrants who have died or left the country make it impossible to calculate those stocks simply on the basis of recorded inward and outward flows. The body responsible for conducting censuses, the Institut National de la Statistique et des Etudes Economiques (INSEE), does record the birthplace of every resident. However, very little of the census data released by INSEE makes any reference to place of birth, and no information at all is collected on the birthplace of people's parents. Only very recently has a limited amount of data on countries of birth been exploited in important studies by Michéle Tribalat and her colleagues at the Institut National d'Etudes Démographiques (INED) (Tribalat 1991, 1993). For most practical purposes, the closest one can get to official information on the ethnic origins of the population - and it is a very rough approximation indeed - is through the data which are published on the nationality status of residents.

The 'common-sense' equation which is often drawn between foreigners and immigrants is seriously flawed. Not all immigrants are foreigners; nor are all foreigners immigrants; significant numbers of people are neither foreigners nor immigrants but are often perceived and treated as such. By focusing on nationality to the exclusion of immigration status or ethnic origins, official data make it extremely difficult to conduct reliable analyses of the impact of immigration on French society at large. The statistical lacunae generated by the state reflect once again an unwillingness at the highest level officially to recognize immigrants and their descendants as structurally identifiable groups within French society.

It is true that most immigrants are foreigners. Foreigners stand, by definition, outside the national community and are formally identifiable on this basis. However, foreigners who fulfil certain residence requirements may apply for naturalization. Others become entitled to citizenship if they marry a French national. All those who acquire French nationality disappear from the official ranks of the foreign population. Censuses do record the previous nationalities of people officially classified as Français par acquisition (i.e. individuals born without French nationality who have since acquired it), but published information of this kind is seldom sufficiently disaggregated to facilitate detailed socio-economic or spatial analyses. Most of the children born to immigrants have until now automatically become French nationals on reaching adulthood, or in some cases at birth, without having to go through any formal application procedures. The grandchildren of immigrants are all automatically French from birth. Strictly speaking, children of foreign birth who become French nationals on reaching the age of majority are Franqais par acquisition', in practice, the great majority are declared in census returns as having been born French (Tribalat 1991: 28). By the same token, they, like all the children and grandchildren of immigrants born with French nationality, are in statistical terms lost without trace. Thus in the official mind of the state, the formal integration of immigrants and their descendants goes hand in hand with their obliteration as a distinct component of French society.

Immigration in French History

This official disappearing act has been matched until very recently by a sustained bout of collective amnesia. There has been very little awareness among the public at large of the contribution of immigrants to the historical development of France (Noiriel 1992b). This forgetfulness is due in part to the paucity of historical research in this field. State formation reached an advanced stage in France at a much earlier point than in many other parts of Europe. The founding myths of the French state were created over many hundreds of years under the centralizing monarchical system which prevailed until the end of the eighteenth century, when they were recast by the French Revolution into the modern forms associated with the ideal of a unified nation-state. The central myths of national identity were thus in place before the rise of large-scale immigration into France during the nineteenth century. Entranced by the spell of those myths, historians in France continued to pay little if any attention to the contribution of immigrants to the national experience even when, by the middle of the twentieth century, sustained migratory inflows had for several generations been an integral part of French society. By contrast, in countries like the US, immigration and nation-building were intimately intertwined. The overwhelming majority of present-day Americans are descended from immigrants who entered the US after its official establishment as an independent state at the end of the eighteenth century. Immigration is in this sense an integral part of American national identity, and it is recognized as such in American historiography (Noiriel 1988; Green 1991).

It was not until the 1980s that the preoccupation with immigration in contemporary France brought an upsurge of interest in historical studies of this phenomenon over a much longer period (Citron 1987; Noiriel 1988; Lequin 1988; Ogden and White 1989). Such studies were long overdue, for it is an important matter of historical fact that during the greater part of the last two centuries France has received more immigrants than any other country in Europe (Dignan 1981). Indeed, for much of the twentieth century, after the US imposed tight quotas in the 1920s, France was the most important country of immigration in the industrialized world. By 1930, foreigners accounted for a larger share of the population in France than they did in the US (Noiriel 1988: 21).

As formally defined by French demographers (Tribalat 1991: 6), immigrants are people born abroad without the nationality of the country in which they now live. On this basis, there are today over 4 million immigrants in France, almost one-third of whom have acquired French nationality. In addition, it is estimated that about 5 million people (the great majority of whom are French nationals) are the children of immigrants, and a similar number have at least one immigrant grandparent. Thus, in all, about 14 million people living in France today - a quarter of the national population of nearly 57 million - are either immigrants or the children or grandchildren of immigrants (Tribalat 1991: 43, 65-71).

In explaining migratory flows, a distinction is usually drawn between 'push' and 'pull' factors. Industrialization, and the country's relatively low rates of natural population growth compared with most of her neighbours, were the principal 'pull' factors inclining France to accept and in some cases actively recruit inflows of foreigners. Heavy population losses suffered during the First World War and to a lesser extent during the Second World War gave an additional impetus to pro-immigration policies. Those who migrated to France felt 'pushed' from their home countries by a variety of factors. Most commonly, these were of an economic nature. When they compared their present circumstances with those they hoped to find elsewhere, migrants motivated by economic considerations calculated that by moving to another country they would have a higher chance of improved living standards. In some cases, political pressures weighed more heavily than purely economic concerns. State persecution of individuals or groups, pursued sometimes to the point of genocide, induced many of those targeted in this way to seek refuge elsewhere. Ever since the revolution of 1789, France has cultivated an international reputation as a country committed to the defence of human rights, making it a natural destination for would-be refugees (Noiriel 1991).

Three further general points should be made concerning the pattern of migratory flows. First, it would be a mistake to view those flows as a mechanical outcome of impersonal forces. While substantial numbers of people have sometimes been forcibly transported from one country to another (as slaves or convicts, for example), most international migrants have themselves made the decision to move. Often, of course, the choice has been made in circumstances in which they would have preferred not to find themselves (such as poverty or persecution), but in each case the decision to migrate has nevertheless depended on an act of personal volition, without which 'push' and 'pull' factors would have been no more than analytical abstractions. One place does not push or pull against or towards another. Places have the power to attract or repel only to the extent that they are perceived positively or negatively within the personal projects constructed by individual human beings (Begag 1989).

Second, the relative weight of push and pull factors may be perceived differently in the sending and receiving states. If unemployment or inter-ethnic tensions rise in a receiving country, voters and politicians may seek to halt or even reverse migratory flows. If, at the same time, the situation worsens or simply remains stable within a sending country where people already consider their lot to be intolerable, they may seek to enter the other country in spite of the barriers placed in their way. Contradictions of this kind have become increasingly visible since the mid-1970s, when most West European states declared a formal halt to inward labour migration. As living standards and political conditions have stagnated or worsened in many African and Asian countries since then, would-be migrants have turned increasingly to illegal modes of entry into European labour markets.

Third, the choice of a particular destination on the part of an individual migrant is always conditioned by a complex set of calculations in which immediate opportunities and constraints are weighed against the chances of securing long-term objectives. Thus countries with less than ideal conditions but relatively low barriers may pull in more migrants than states that are perceived as highly attractive but to which access is tightly policed. Geographical proximity, transport systems and social networks based on friends or relatives who have already migrated may also play a role.

During a large part of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, French perceptions of the need for immigrants, and more particularly immigrant workers, dovetailed more or less closely with the calculations made by would-be or actual migrants in nearby countries. There have, however, been important exceptions to this pattern. An economic downturn in the late nineteenth century was marked by growing antagonism towards foreign workers in some sections of French society, particularly those who feared for their jobs. Anti-Italian sentiments became especially strong in southern France, where a number of violent attacks took place. The most serious of these occurred in 1893 at Aigues-Mortes, where at least eight Italians were killed and dozens more were injured. During the slump of the 1930s, the French authorities organized the forcible repatriation of trainloads of Poles (Ponty 1988: 309-18).

Until the First World War, France exercised only weak immigration controls, effectively leaving most population movements to the free play of market forces. Even after official controls were insti-tuted,2 these were often circumvented with the more-or-less open connivance of the state. For example, the majority of immigrant workers who entered the French labour market during the economic boom of the 1960s did so illegally, but the state was happy to 'regularize' their situation ex post facto by issuing residence and work permits to foreigners who, by taking up jobs, were helping to ease labour shortages. Even today, when the state appears to be more earnest in its opposition to illegal immigrants, many find jobs (usually of a precarious and poorly paid nature) because their employers calculate that their own interests are well served by the recruitment of undocumented workers. In this way, employers bypass and yet at the same time benefit from the regulatory intervention of the state, for the fear of deportation prevents undocumented workers from complaining about poor wages or working conditions.

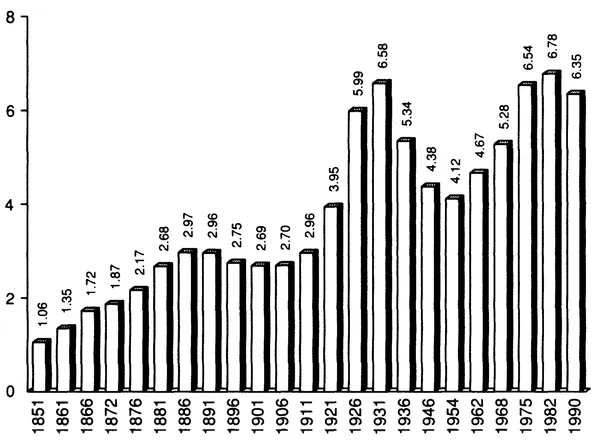

Figure 1.1 Foreigners as percentage of total population of France, 1851-1990 Source: INSEE 1992a: Tables R2, R3.

During the nineteenth century, labour shortages in France's expanding industrial sector induced considerable internal migration from rural to urban areas. However, these internal population flows proved insufficient to meet the demand for labour, and foreign workers came in increasing numbers. Census data on the foreign population were first collected in 1851. Figure 1.1 shows the number of foreigners, expressed as a percentage of the total population, at every census conducted since then. It shows a steady rise in the foreig...