![]()

Chapter 1

Ancient Greek Writing Instruction and Its Oral Antecedents

Richard Leo Enos

Key Concepts

Oral culture, Memory versus writing, Tally systems, Alphabet, Writing as a craft skill, Techne, Stichometry, Orthography, Abecedaria, Thetes, Helots, Writing and thinking, Literacy, Women and writing, Family education and sumposia, Progymnasmata as graded composition exercises, Paideia, Aoidoi, Homeric rhapsodes, Syllabaries, Linear A and Linear B, Sophists, Logography, Ostraka, Graffiti and dipinti, Melete, Rhetoric, Writing in education, Plato’s objections to writing, Aristotle’s use of writing, Writing as an intellectual process, Isocrates’s curriculum based on talent, practice and experience, Letteraturizzazione.

A good song, I think. The end’s good—that came to me in one piece—and the rest will do. The boy will need to write it, I suppose, as well as hear it. Trusting to the pen; a disgrace, and he with his own name made. But write he will, never keep it in the place between his ears. And even then he won’t get it right alone. I still do better after one hearing of something new than he can after three. I doubt he’d keep his own songs for long, if he didn’t write them. So what can I do, unless I’m to be remembered only by what’s carved in marble?

The opening passage by the poet-rhapsode Simonides in the Mary Renault novel, The Praise Singer

Overview

Conventional approaches to understanding writing instruction in ancient Greece typically draw upon well-established literary sources. We have learned a great deal about writing instruction from the corpus of ancient writers and this work is synthesized in the present chapter. In addition, non-traditional literary sources, such as fragments of writing on durable materials and the instruments of writing, have come to light, and these primary sources also add to and refine our understanding of writing instruction. As with the previous edition, Athens is an understandable focal point of study, not only because this powerful and enduring city-state is widely regarded as the first literate community in ancient Greece and offers a substantial amount of evidence for examination, but also because new sources of evidence have come to light in recent decades that tell us a great deal more about Athens as a literate community. Archaeological excavations in the Agora, for example, have unearthed inscriptions and related artifacts that now provide new evidence about everyday writing habits. These new resources—in the form of graffiti and dipinti—expand and deepen our knowledge of what community literacy* meant in ancient Athens and, correspondingly, the attendant modes of instruction that accompanied a variety of writing functions.

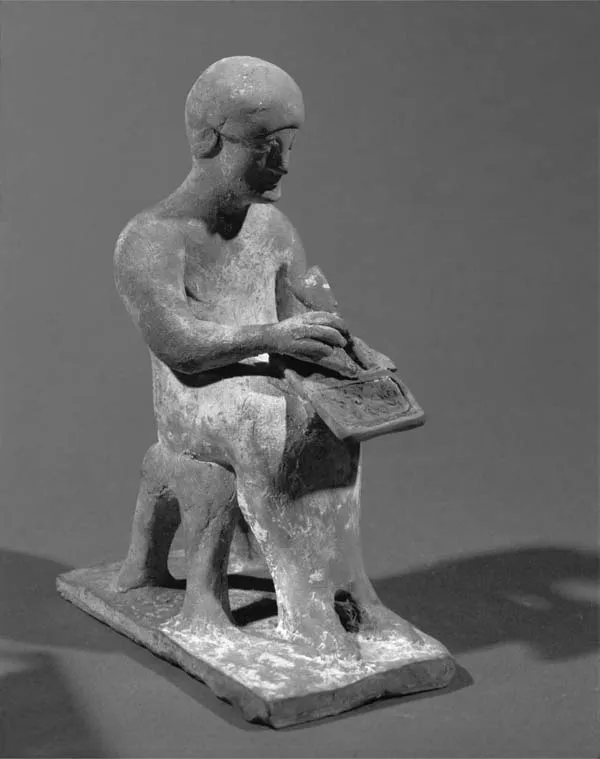

Figure 1.1 Sitting scribe. Greek terracotta figurine from Thebes, Boeotia. 1st quarter 6th BCE. Location: Louvre, Paris, France.

(Photo Credit: Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY)

While the present chapter again concentrates on Athens, this chapter also includes brief perspectives on writing instruction from other prominent Greek city-states. For example, extensive study at Rhodes, Sparta and Thebes reveals not only rival manifestations of rhetoric but also correspondingly different approaches to the teaching of writing. Research on these city-states, unlike Athens, is at an early stage. However, what we will find when we examine the rhetorical practices of non-Athenian Hellenic rhetoric is that the approaches are driven by the specific preferences of cultures. For some, such as Athens, writing for civic and educational purposes was important. For others, such as was the case with Sparta, effective written communication in battle situations was critical. For still others, such as Rhodes, rhetoric that stressed cross-cultural issues was emphasized. Correspondingly, the instructional approaches vary in ways that correspond to the orientations of rhetoric. Of course, it would be impossible to discuss the full variety of writing instruction across the city-states of ancient Greece in one chapter, but alternate examples illustrating the diversity of writing instruction explain why certain educational approaches emphasized different features of writing in their instruction, and make clear the necessity of more field work in this area of study.

This chapter discusses not only the sites of writing instruction, but also the range of writing instruction for different groups and functions. Writing instruction, as indicated above, was wide-ranging in practice as a response to an array of socially determined needs. The hope in providing this spectrum is to illustrate the range of writing instruction in ancient Greece and to adjust long-standing (but often imprecise) views. We often assume, for example, that writing is for the privileged few. We now understand, however, that some writing was done as a functional craft practiced by artisans of the thetes class with instruction in the form of a labor skill. This writing instruction goes well beyond the training of scribes, who often recorded documents for religious and civic purposes. Such new evidence provides a more comprehensive view of both civic literacy and also the spectrum of writing instruction ranging from writing as an aspect of early education, writing in everyday social interaction, writing as a trade-skill, and writing at the most sophisticated and highest levels of advanced education. In a similar respect, it is important to discuss writing instruction and women in ancient Greece. The long-held belief that women were not literate needs to be reconsidered and qualified. For example, evidence examined a few years ago at the British Museum suggests that literacy was not uncommon among certain classes of Athenian women (see Figure 1.2).1 Finally, and because ancient Greeks faced the challenge of communicating effectively, this chapter also examines writing instruction for such cross-cultural purposes as commercial transaction with Phoenicians, Carthaginians and Etruscans.

Figure 1.2 Painter of Bologna 417 (5th century BCE). Two schoolgirls, one holding a writing tablet. Terracotta kylix (drinking cup) ca. 460–450 BCE. Location: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, USA.

(© The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource, NY)

Issues of Historiography and Writing Instruction in Ancient Greece

The history of writing instruction in ancient Greece is, in one respect, a record of the discoveries of the powers of literacy and how those powers could be taught systematically. At first glance, the study of writing instruction does not appear to seem complex, but there are issues of historiography that must be noted. If we consider “literacy” to be nothing more than acquiring the skill of how to read and write, then writing instruction would be nothing more than learning the rudiments of a recording technique that would serve as an aid to memorizing speech. However, it is important to stress the complex, endemic relationship that existed among reading, writing and speaking in ancient Greece. We tend to think of writing instruction as a separate category from oral instruction, but the interrelation of orality with literacy was much closer than our current perspectives reveal. Writing instruction was (eventually) integrated with, and became a part of, “oral” instruction, as is clearly evident when we examine Greek declamation.2 From its inception in Greece, however, writing developed for reasons other than as an aid to memory for speech. Writing also served as a technology for quantitative memory and problem-solving in early mathematical accounting. In identifying and examining these methods of invention we should also acquire a more detailed understanding of the mentality of cognition and expression. In the past, insights to the cognitive processes that structure meaning have been through the study of theory and performance. An understanding of instruction will provide another critical perspective on the relationship between thought and expression in ancient Greece.

Pre-Alphabetic Influences on Writing Instruction

Before writing, of course, Greece was exclusively an oral culture. Thoughts and sentiments were preserved by long-term memory and transmitting those thoughts from mentor to apprentice as a form of oral instruction. While long-term memory was valued in Greek culture it was hardly a widespread trait and required considerable skill and training. Mastering the craft-techniques of oral composition and memory-training led to the guild of aoidoi and later to rhapsodes; these experts, memorizing massive amounts of language for preservation and transmission, viewed their techne as a specialized craft that required years of training and is often associated with the origins of rhetoric. Controlling Greek “literature” was the craft of the expert rhapsode and not a broad-based public skill. During this purely oral rhapsodic stage, heuristics for oral composition were developed and taught long before rhetoric became a discipline. Writing in pre-alphabetic Hellenic cultures was also an aid to memory but was used more for economic and mathematical functions than prose recording. Writing instructors were those who transmitted skill in using tally systems for accounting purposes.

Eventually, when scripts evolved to an alphabetic system, writing came to complement, and later replace, the need for long-term memory of oral discourse. Even at that stage, however, the ties between writing, reading and speech remained particularly strong in ancient Greece and persisted for centuries. In fact, there is very good reason to believe that most ancient Greeks never learned to read silently.3 Of course, even from this perspective, writing instruction would be a tremendous skill if it were nothing more than simply a recording device. Yet, writing evolved into much more than an aid to memory, particularly with the evolution of the alphabet, and these changes had enormous consequences for the instruction of writing in Greece.

Alphabetic Influences on Early Writing Instruction

In one respect, writing itself is a technology and, in ancient Greece, the alphabet is the essence of that technology. By modification and adaptation of earlier Semitic scripts, ancient Greeks were able to construct a writing system that evolved to only twenty-four letters, each of which was intended to capture a discrete but essential sound of the utterances of their language. When arranged together, these discrete sounds could be echoed to reconstruct the vocal patterns of everyday speech. The alphabet was ingenious in its simplicity and monumental in its impact. Earlier pre-alphabetic writing systems were, by comparison, slow, cumbersome, complex and imprecise. The alphabet, however, could be easily learned and written—even by children—and readily remembered. It is also important to note that the alphabet made this recording device very easy to learn and to use; instruction, accordingly, moved from a specialized craft skill done for purposes of tally, accounting and computation, to a skill easily mastered by non-experts involved in public discourse. More advanced mathematical systems initially used the alphabet for computation before adopting the later Arabic system of pure numbers. Geometry, of course, is one of the exceptions that persisted (to a degree) in continued use of the Greek alphabet.

Writing could provide the conditions where not just an expert but also even an entire community—such as Athens—could be literate. Eventually, this shift would move writing instruction from a specialized craft-skill to an aspect of civic education. Writing has demonstrable benefits over “oral” techniques that are used to stimulate long-term memory far beyond tally and recording heuristics. Writing with the alphabet created the procedure used by early Greeks to capture the fleeting, momentary utterances of oral discourse. Accordingly, instruction in writing would be “democratized” in the sense that it could easily be taught to the public and move from a specialized craft-skill to a public activity and, in this sense, taught to the public as a way of facilitating civic affairs, such as the law courts and political assemblies.

In his volume, A Study of Writing, I. J. Gelb asserts that the Greek development of the alphabet was “the last important step in the history of writing.”4 For those of us who wish to better understand the history of writing instruction in ancient Greece, the opposite view would seem to be true. That is, the devising of the alphabet signals the beginning of widespread writing instruction in ancient Greece. If we take Gelb’s remark to mean that the structure of writing was so ingeniously simplified that any child could learn to write and, therefore, any advancement would only be limited to adding or modifying letters, then we would agree with Gelb’s view. Writing instruction in ancient Greece, however, was much more than imparting directions about the arrangement of individual letters of the alphabet. With the alphabet, writing took on rhetorical functions and, in turn, the instruction of writing changed dramatically from a craft skill to also include what would eventually evolve into an art or techne of social power.

Writing Instruction and Civic Power

W...