1

HAPPENINGS

An Introduction

Michael Kirby

There is a prevalent mythology about Happenings. It has been said, for example, that they are theatrical performances in which there is no script and “things just happen.” It has been said that there is little or no planning, control, or purpose. It has been said that there are no rehearsals. Titillating to some, the object of easy scorn to others, provocative and mysterious to a few, these myths are widely known and believed. But they are entirely false.

It is not difficult to see why these spurious concepts developed. Myths naturally arise where facts are scarce. Those people who have actually attended even one performance of a Happening and have what might be considered firsthand information are relatively few. Individual audiences have generally been small—they have rarely exceeded one hundred and are usually close to forty or fifty. Productions have been limited to a few performances, and almost all of the artists would reject the idea of “revivals.”

Many spectators attended Happenings merely as entertainment. Without concern for the work as art, they noticed only the superficial qualities. In others, the tendency to view everything in terms of traditional categories, making no allowance for significant change, made evaluation difficult. Thus, even among the limited number of people who have been able to see Happenings, a primary distortion has taken place.

Secondary distortion has occurred in the dissemination of information about Happenings. Once people have heard about Happenings, there is the problem of finding one to see. In this atmosphere where facts are scarce, any information takes on much greater significance. The name itself is striking and provocative: it seems to explain so much to someone who knows nothing about the works themselves. And, intentionally or by accident, there have been incorrect and misleading statements in newspapers and magazines. Writing about the Happenings in Claes Oldenburg’s store, for example, the New York Times stated that, “Mr. Oldenburg and his actors do not follow a script or rehearse.” Such a statement naturally has a much wider audience than the works themselves. When a motionless nude appeared on a balcony behind the audience in a Happening at the Edinburgh Drama Festival, all other details of the work were lost in a welter of news items that mentioned only the girl. Although the peculiar, bizarre, and titillating may be more worthy of space in the mass media by their own standards than are serious creative works whose originality makes them difficult or even obscure for many people, this commercial emphasis functions as an instrument of distortion.

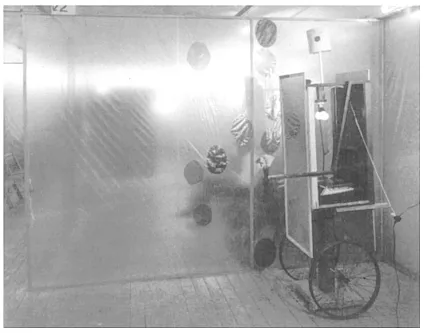

The “sandwich man” from Allan Kaprow’s 18 Happenings in 6 Parts (1959).

Despite Kaprow’s initial protestations and the objections of other artists, the media picked up on the title as a label for the emerging genre. (Photo by Scott Hyde.)

But if Happenings are not improvisations by a group of people deciding to exhibit themselves at a party; if they are not sophisticated buffoonery designed to give a deceitful impression of profundity nor uncontrolled orgies of audience participation, what are they?

Not all were called Happenings by their creators. The poster for Red Grooms’ The Burning Building (1959) called it “a play”; Robert Whitman refers to his works as “theatre pieces,” and Oldenburg uses Ray Gun Theater. Even Allan Kaprow’s earliest public work, from which the name originated, was not called a Happening but 18 Happenings in 6 Parts (1959). Each has attempted to defend the unique and personal qualities of his work from the destructive, leveling influences of superficial categorization and misleading comparisons, but the word “Happening” has been used long enough by a sufficient number of knowledgeable people to give it a certain validity.

[…] The germinal development of the Happening was in New York, and, although they have since been presented in other parts of the country and in Europe, this formative propinquity is another reason to treat these works as a formal entity.

Happenings did not develop out of clear-cut, intellectual theory about theatre and what it should or should not be. No commonly held definition of a Happening existed before the creation of these particular works. If a definition is to be arrived at now, it must be inclusive enough to take in all of these works and rigorous enough to exclude works that, although they might have a certain resemblance, are not commonly referred to as Happenings.

Although some of their advocates claim they are not, Happenings, like musicals and plays, are a form of theatre. Happenings are a new form of theatre, just as collage is a new form of visual art, and they can be created in various styles just as collages (and plays) are.

On the surface, the Happenings had certain similarities of stylistic detail in production. As can be seen from the photographs, Happenings have had in common a physical crudeness and roughness that frequently trod an uncomfortable borderline between the genuinely primitive and the merely amateurish. This was partly intentional, due to their relationship with action painting and so-called junk sculpture, and partly the inevitable result of extremely limited finances. All of the Happenings—except, of course, the later ones presented outdoors—were put on in lofts and stores, in limited spaces for limited audiences. But such similarities are not important: they do not define the essence of the work. If more money, larger spaces, or more elaborate equipment had been available, the productions would have been changed somewhat, but the defining characteristics are to be found beneath these superficialities.

[…] The fact that the first Happening in New York and many succeeding ones were presented in the Reuben Gallery—sometimes on the same three—or four-week rotation schedule that is common with art galleries—serves to emphasize the fundamental connection of Happenings with painting and sculpture. Could Happenings be called a visual form of theatre?

Certainly they are not exclusively visual. Happenings contain auditory material and some have even used odor. To say that they are primarily visual, which is true, loses its importance when it is realized that sight has dominated much of traditional theatre. Pantomime and dance are obvious examples, but many individual directors of verbal drama have stressed, like Gordon Craig, “the priority of the eye.” Nor, like the Munich Artists’ Theatre of 1908 that learned from painters and sculptors how to turn a play into something resembling a bas-relief that moved, can Happenings be called “pictorial.” They have rejected the proscenium stage and the conceit that everyone in the auditorium sees the same “picture.” In many Happenings there is a great difference, in both amount and quality, in what is seen by different spectators.

But Happenings do have a nonverbal character. While words are used, they are not used in the traditional way and are seldom of primary importance. […] In 18 Happenings in 6 Parts and The Burning Building stream-of-consciousness monologs in the more-or- less traditional sense are used. Although they are repetitious and discursive, these verbal structures make use of associations and accumulative meaning in addition to affective tone. But some of the monologs in 18 Happenings in 6 Parts are merely random lists of words and phrases, sometimes chosen and arranged completely by chance methods, and an abstract “conversation” occurred in The Burning Building when two performers alternately uttered staccato words and phrases. Here the word “structure” has completely abandoned the power of syntax. It is separated from the usual progressive associations and accumulative meaning and functions as a vocal entity in which pure sound values tend to predominate.

Sound values do predominate in preverbal material […]. Used quite frequently, it can most significantly be understood as verbal effect. Thus it obviously cannot be said that Happenings do not make any use of language. Although noise and music predominate, they are far from being pantomime. But Happenings are essentially nonverbal, especially when compared to traditional theatre whose substance is vocal exchange between characters.

Of even greater importance is the fact that Happenings have abandoned the plot or story structure that is the foundation of our traditional theatre. Gone are the clichés of exposition, development, climax, and conclusion, of love and ambition, the conflicts of personality, the revelatory monolog of character. Gone are all elements needed for the presentation of a cause-and-effect plot or even the simple sequence of events that would tell a story. In their place, Happenings employ a structure that could be called insular or compartmented.

Traditional theatre makes use of an information structure. There we need information in order to understand the situation, to know who the people are, to know what is happening, or what might happen; we need information to “follow” the play, to apprehend it at all. Much of this information is visual, conveyed by the set, the lights, the expressions and movements of the actors, and much of it is contained in spoken words. This information is essentially cumulative. Although “exposition” conventionally is placed early in the play, additional information is provided by each element. But information structure also functions reflexively, explaining and clarifying material that has already been presented.

Compartmented structure is based on the arrangement and contiguity of theatrical units that are completely self-contained and hermetic. No information is passed from one discrete theatrical unit—or “compartment”—to another. The compartments may be arranged sequentially […] or simultaneously […]. 18 Happenings in 6 Parts is a clear example of both simultaneous and sequential compartmentalization: the physical structure of the three separate rooms emphasizing the isolation of units functioning at the same moment, and the six separate “parts” underline the disjunction in continuity.

This does not mean that Happenings have no structure. A three-ring circus, using both simultaneous and sequential “compartmentalization,” exists as an experiential entity with its own character and overall quality. A well-arranged variety show has a unity of style and a cohesiveness that makes it a show. But beyond this it has been demonstrated in other fields of art that a work does not require information structure. Although each of the photographs and objects in a Robert Rauschenberg “combine,” for example, conveys information, they do not relate to each other in any logical way: they exist in simultaneous compartments. Ignoring “program music” and intellectual “explanations,” a unity exists in the separate movements of a symphony even though the formal differences between them may be large. […]

It should be noted that the terms “scene,” or even “hermetic scene,” and “compartment” are not the same. “Scene” has primary reference to people and to place. A scene is “played” between actors and by an actor. A“French scene” begins and ends with the entrance or exit of a major character. But many units in Happenings contain only sounds or physical elements, and not performers. Frequently, although performers are in physical proximity, there is no interplay between them, and an imaginary place […] is seldom established.

It is when we look within the compartments in this manner and study the various theatrical elements—principally the behavior of the performers themselves—that another essential characteristic of Happenings becomes clear. In traditional theatre, the performer always functions within (and creates) a matrix of time, place, and character. Indeed, a brief definition of acting as we have traditionally known it might be the creation of, and operation within, this artificial, imaginary, interlocking structure. When an actor steps onstage, he brings with him an intentionally created and consciously possessed world, or matrix, and it is precisely the disparities between this manufactured reality and the spectators’ reality that make the play potentially significant to the audience. This is not a question of style. Time-place-character matrices exist equally in Shakespeare, Molière, and Chekhov. Nor is it equivalent to the classic “suspension of disbelief,” although the matrix becomes obvious when pressure is applied to it. (This pressure can be intentional, as in Six Characters in Search of an Author, where we seem to be asked to believe that these new people onstage are not actors inside of characters but characters without actors; or unintentional, as when Bert Lahr loses his place in the confusingly similar lines of Waiting for Godot and, starkly out of character, confides to the audience, “I said that before.”) Presentational acting and devices designed to establish the reality of the stage-as-a-stage and the play-as-a-play do not eliminate matrix. Nor do certain characters who function in the same time and place as the audience rather than that of the other roles: the Stage Manager in Our Town, Tom in The Glass Menagerie, Quentin in After the Fall. Even in musical comedies, which interrupt the story line with little logical justification for a song or dance in which the personality of the performer himself predominates, the relationship of mood and atmosphere to situation and plot is retained, and the emotions and ideas expressed are obviously not those of the singer or dancer himself.

Time-place matrices are frequently external to the performer. They are given tangible representation by the sets and lighting. They are described to the audience in words. Character matrices can also be external. For example, the stagehands rearranging the set of Six Characters in Search of an Author may be dressed like real stagehands and function like real stagehands (they may even be real stagehands), and yet, because of the nature of the play that provides their context, they are seen as “characters.” As part of the place-time continuum of the play, which happens to include a stage and the actual time, they “play roles” without needing to “act.” They cannot escape the matrix provided by the work. Even when one of the actors in The Connection approaches you during the intermission to ask for a handout (as he has promised to do from the stage during the first act), he is still matrixed by character. He is no longer in the physical setting of the play, and he is wearing ordinary clothes that seem disreputable but not unreal in the lobby, but neither these facts nor any amount of improvised conversation will remove him from the character-matrix that has been produced.

Since time and place may be ambiguous or eliminated completely without eliminating character (i.e., time and place both as external, physical, “environmental” factors and as elements that may be subjectively acted by a performer), role-playing becomes primary in determining matrix. By returning from the lobby too soon or sitting through the intermission of a production performed on a platform stage with no curtain to conceal the set changes, one can see the stagehands rearranging props and furniture. Although some productions might rehearse mimes or costumed bit players for these changes, most would just expect you to realize that this was not part of the play. The matrices are neither acted nor imposed by the context: the stagehands are “nonmatrixed.” This is exactly what much of the “acting” in Happenings is like. It is nonmatrixed performing.

A great variety of nonmatrixed performances take place outside of theatre. In the classroom, at sporting events, at any number of private gatherings and public presentations there is a “performer-audience” relationship. The public speaker can function in front of an audience without creating and projecting an artificial context of personality. The athlete is functioning as himself in the same time-place as the spectators. Obviously, meaning and significance are not absent from these situations, and even symbolism can exist without a matrix—as exemplified in religious or traditional ritual or a “ceremony” such as a bullfight. In circuses and rodeos, however, the picture becomes more complex. Here clowns who are strongly matrixed by character and situation function alternately with the nonmatrixed performances of the acrobat and the broncobuster. The distinction between matrixed and nonmatrixed behavior becomes blurred in nightclubs, among other places. The stand-up comedian, for example, may briefly assume a character for a short monolog and at other times present his real offstage personality. From the clearly nonmatrixed public speaker to the absolutely matrixed performer delivering a “routine,” there is a complete continuum. Yet the concept of the nonmatrixed performer is still valid, as in the case of the football player making a tackle, the train conductor calling out stops, even the construction worker with his audience of sidewalk supervisors. A difference of opinion has traditionally existed between the “monists” such as Stanislavsky, who felt that the performer should be unseen within his character, and “dualists” such as Vakhtanghov and Brecht, who felt that the performer should be perceived simultaneously with the character so that the one could comment on the other. Now a new category exists in drama, making no use of time, place, or character and no use of the performer’s comments.

Let us compare a performer sweeping in a Happening and a performer sweeping in traditional theatre. The performer in the Happening merely carries out a task. The actor in the traditional play or musical might add character detail: lethargy, vigor, precision, carelessness. He might act “place”: a freezing garret, the deck of a rolling ship, a windy patio. He might convey aspects of the imaginary time situation: how long the character has been sweeping, whether it is early or late. (Even if the traditional performer had only a bit part and was not required to be concerned with these things, he would be externally matrixed by the set and lights and by the information structure.)

If a nonmatrixed performer in a Happening does not have to function in an imaginary time and place created primarily in his own mind, if he does not have to respond to often-imaginary stimuli in terms of an alien and artificial personality, if he is not expected either to project the subrational and unconscious elements in the character he is playing or to inflect and color the ideas implicit in his words and actions, what is required of him? Only the execution of a generally simple and undemanding act. He walks with boxes on his feet, rides a bicycle, empties a suspended bucket of milk on his head. If the action is to sweep, it does not matter whether the performer begins over there and sweeps around here or begins here and works over there. Variations and differences simply do not matter—within, of course, the limits of the particular action and omitting additional action. The choices are up to him, but he does not work to create anything. The creation was done by the artist when he formulated the idea of the action. The performer merely embodies and makes concrete the idea.

Nonmatrixed performing does not eliminate the factor of ability, however. […] Nor is all performing in Happenings nonmatrixed. Character and interpretation have sometimes been important and traditional acting ability has been required. This was especially true in Oldenburg’s productions at his store when he employed a “stock company” of himself, his wife Pat, and Lucas Samaras in every performance. On the other hand, Whitman, in an attempt to prevent “interpretation,” prefers not to explain “meanings” to his performers.

Although entrances and exits may occasionally be closely cued, the performer’s activities are very seldom controlled as precisely as they are in the traditional theatre, and he generally has a comparatively high degree of freedom. It is this freedom that has given Happenings the reputation of being improvised. “Improvised” means “composed or performed on the spur of the moment without preparation,” and it should be obvious that this definition would not fit the Happening as an artistic whole. Its composition and performance are always prepared. The few Happenings that had no rehearsal were intentionally composed of such simple elements that individual performers would have no difficulty in carrying them out, and in many of the works the creators themselves took the major roles.

Nor would it be accurate or precise to say that even the small units or details of Happenings are improvised. For one thing, the word already has specific references— primarily to the commedia dell’arte, various actor-training techniques connected with the Stanislavsky method, and certain “improvisational theatres” (such as Second City and The Premise)—which have no significant relati...