This is a test

- 280 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Dick Hebdige looks at the creation and consumption of objects and images as diverse as fashion and documentary photographs, 1950's streamlined cars, Italian motor scooters, 1980's 'style manuals', Biff cartoons, the Band Aid campaign, Pop Art and promotional music videos. He assesses their broad cultural significance and charts their impact on contemporary popular tastes.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Hiding in the Light by Dick Hebdige in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Arte & Cultura popolare nell'arte. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Section One:

Young Lives

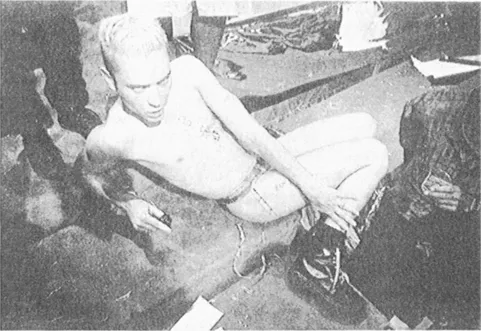

Showing off in public is a natural outlet for the arrogance of the young spiv. Immaculately dressed, he seeks admiration from girls (original caption)

Chapter 1

Hiding in the Light: Youth Surveillance and Display

I shall begin with a proposition – one that is so commonplace that its significance is often overlooked – that in our society, youth is present only when its presence is a problem, or is regarded as a problem. More precisely, the category “youth” gets mobilised in official documentary discourse, in concerned or outraged editorials and features, or in the supposedly disinterested tracts emanating from the social sciences at those times when young people make their presence felt by going “out of bounds”, by resisting through rituals, dressing strangely, striking bizarre attitudes, breaking rules, breaking bottles, windows, heads, issuing rhetorical challenges to the law.

When young people do these things, when they adopt these strategies, they get talked about, taken seriously, their grievances are acted upon. They get arrested, harassed, admonished, disciplined, incarcerated, applauded, vilified, emulated, listened to. They get defended by social workers and other concerned philanthropists. They get explained by sociologists, social psychologists, by pundits of every political complexion. In other words, there is a logic to transgression.

When disaffected adolescents from the inner city, more particularly when disaffected, inner city unemployed adolescents resort to symbolic and actual violence, they are playing with the only power at their disposal: the power to discomfit. The power, that is, to pose – to pose a threat. Far from abandoning good sense, they are acting in accordance with a logic which is manifest – that as a condition of their entry into the adult domain, the field of public debate, the place where real things really happen, they must first challenge the symbolic order which guarantees their subordination by nominating them “children”, “youngsters”, “young folk”, “kids”.

striking poses …

To take one of the more sensational examples: when youths in the inner cities rioted in July, 1981, they were visited by senior police officials, journalists, the prime minister and Michael Heseltine. They got noticed. Their portraits appeared in the Daily Mail and Camerawork, The People and Ten.8. They became visible. The machinery of social reaction was set in motion and this reaction had varied, even contradictory effects. For those youths who got arrested and arraigned before the courts, the riots meant fines or imprisonment, criminalisation, the confirmation, possibly, of a criminal career. More generally, the riots triggered off debates concerning the nature of policing in the 1980s, the problem of youth unemployment, the erosion of parental discipline, the implications for Britain's most depressed communities of government cuts in welfare, housing, education. Money was suddenly found for limited job creation and youth opportunity schemes. Community policing programmes were floated and assessed. Attention was drawn to the damage caused by Thatcherite intransigence. At the same time, the riots served to harden the law and order lobby's opposition to the principle of “no go areas”, and were cited in parliamentary debates to justify the drift into coercion: the introduction of the “short sharp shock centres”, water cannon, tear gas, battle dress, the transplantation of the full technology of crowd control from Northern Ireland to the mainland.

All these conflicting possibilities were licensed by what happened that July, by the riots, the reports and the syndicated photographs of riots: bleak studies of shattered glass, burning buildings and violent confrontation. Those photographs recall a familiar iconography, the iconography of the American city-in-crisis, and were filtered through the negative mythology surrounding the American metropolis where the city functions as a symbol of the “modern malaise”. For the last ten years, since the mugging panic of the early 1970s, the predatory instincts of this imaginary city, its pathology, have been concentrated in a single image: “The image of the mugger erupting out of the urban dark in a violent and wholly unexpected attack”.1

In July, 1981, that iconography was extended. Behind the headlines, the parliamentary debates and independent enquiries, lurked the familiar spectre of the solitary black mugger only now he (and almost invariably it is a “he”) had been collectivised. A new collective subject was proposed – the “mass mugger” – the unruly, resentful and delinquent black mob.

That's just one example. But the issues raised by the media representation of the riots – issues concerning the marginalisation and scapegoating of black youth, the sources and uses of stereotypical images of the “youth problem” – are so self-evidently serious that they sometimes threaten to obscure the significance of other forms of cultural resistance amongst youth. Pictures of punks and mods and skinheads, for instance, are commonly regarded, even amongst many documentary practitioners, as unproblematic, or as distractions from the real issues: visually interesting but ideologically suspect. The subcultures themselves are dismissed on the grounds that they are sexist/racist/brutalised/narcissistic/commodified/incorporated: “commercial” not “political”.

I want to question that puritanical distinction between youth in its “commercial” and “political” guises, in its “compromised” and “pure” forms, the distinction, that is, between the youth market and the youth problem, between youth-as-fun and youth-as-trouble – an opposition which I hope to show has been codified into two quite different styles of photography. I want to challenge that distinction between “pleasure” and “politics”, between “advertisements” and “documentaries” and to pose instead another concept: the politics of pleasure. This will entail tracing back in a rather schematic way, the historical development of youth as a loaded category not only within photography but also within certain branches of journalism and the social sciences.

… posing threats

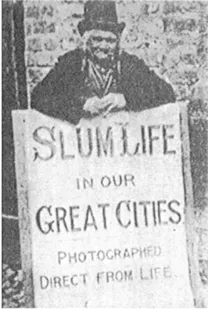

Youth and the Silent Crowd

The definition of the potentially delinquent juvenile crowd as a particular urban problem can be traced back in Britain at least to the beginnings of the Sunday School movement – an attempt on the part of the church to extend its moderating influence downwards in terms both of social class and biological age.2 Haphazard urbanisation, child factory labour and the physical and cultural separation of the classes into two separate “nations” were together held responsible for creating a new social problem: the unsupervised, heathen working-class juvenile who appears in contemporary novels, journalism and early parliamentary reports as a symptom of the industrial city, which is itself typically presented in this literature as a “monstrous” and “unnatural” place.

One image recurs: the silent crowd, anonymous, unknowable, a stream of atomised individuals intent on minding their own business. One of the major threats which the urban crowd seems to have posed for literate bourgeois observers lay in the perception that the masses were illegible as well as ungovernable.3 Indeed, the two threats, the crowd's opacity and its potential for disorder, were inextricably connected.

Children and adolescents were regarded as a particular problem. During the mid-nineteenth century when intrepid social explorers began to venture into the “unknown continents”, the “jungles” and the “Africas” – this was the phraseology used at the time – of Manchester and the slums of East London, special attention was drawn to the wretched mental and physical condition of the young “nomads” and “street urchins”. The most celebrated “sighting” of a working-class youth subculture in this period occurs in Henry Mayhew's London Labour and the London Poor (1851), in a section devoted to the quasi-criminal costermongers.

The costers were street traders who made a precarious living selling perishable goods from barrows.4 The young coster boys were distinguished by their elaborate style of dress – beaver-skin hats, long jackets with moleskin collars, vivid patterned waistcoats, flared trousers, boots decorated with hand-stitched heart and flower motifs, a red “kingsman” kerchief knotted at the throat. This style was known in the coster idiom as looking “flash” or “stunning flash”.

The costers were also marked off from neighbouring groups by a developed argot – ba...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Section 1: Young Lives

- Section 2: Taste, Nation and Popular Culture

- Section 3 Living on the Line

- Section 4 Postmodernism and “The Other Side”

- Notes

- Index