![]()

Introduction

Barbara A. Wilson

Unlike damage to a limb or indeed even another organ, damage to the brain can be debilitating to an extent that those injured remain dependent on others for the rest of their lives. Except in rare circumstances, a brain cannot be substituted by an artificial device or treated back to its original form or capacity, so brain injured people have to learn how to live their lives with handicaps that are not going to disappear over time.

In recent times workers in the field of neuro-rehabilitation have built up an extensive knowledge of the consequences of injury to the brain, they have developed sophisticated ways of analysing and diagnosing problems faced by brain injured people, and they have developed scien-tifically supported methods of treatment. The neuropsychologists who have contributed to this book have been able to draw upon an extensive literature of research and treatment as well as their own experiences in the field of brain injury rehabilitation. We stress again, however, that what makes this book unique is that the team of authors has been extended to include brain injured survivors themselves, thereby providing as full an account of brain injury and its consequences as possible. We are fairly confident that this book goes deeper and further than most if not all other books describing case studies dealing with the effects of brain injury, which rarely if ever include the story from the patient's point of view, and that barely touch upon the intricacies and efforts involved in brain injury rehabilitation.

There is much misunderstanding about the nature and consequences of brain injury and unfortunately this sometimes extends into the professional community and even exists among medical and political authorities who ought to know better! It is far too easy for some in authority, who do not wish to use some of the funds for which they are responsible, to accept that once a person can walk out of a hospital nothing else needs to be done. This is rarely the case for someone who has received an insult to the brain. Holders of the country's purse strings can easily be seduced by modern technology, preferring to spend money on machines that can light up colours in the brain but cannot as yet indicate treatment for the individuals whose brains light up! Meanwhile professionals working in neuro-rehabilitation are starved of funding despite the fact that brain injured people are convincingly helped to lead better daily lives after receiving treatment at the hands of clinical and neuropsychologists, occupational therapists and speech and language therapists. The irony is that brain injured people who do not receive the sort of rehabilitation described in this book can ultimately become a much larger financial burden upon the state. Rehabilitation not only makes life better for brain injured patients and their families, it also makes economic sense.

There is evidence to show that rehabilitation may be expensive in the short term but it is cost effective in the long term (Prigatano & Pliskin, 2002; Winegardner & Ashworth, 2012). There are several studies suggesting that rehabilitation for survivors of brain injury is economically effective. For example, Cope et al. (1991) surveyed 145 American patients and found that the estimated saving in care costs following rehabilitation for a person with severe brain injury was over £27,000 ($40,500) per year. The number of people requiring 24 hours per day care dropped from 23% to 4% after rehabilitation. A Danish study (Mehlbye & Larsen, 1994) reported that expenditure in health and social care for patients attending a non-residential programme were recouped in five years. The costs of not rehabilitating people with brain injury are considerable given the fact that many are young with a relatively normal life expectancy (Greenwood & McMillan, 1993). Cope (1994) suggests that post-acute rehabilitation programmes can produce sufficient savings to justify their support on a cost–benefit basis.

On a slightly different theme, a study by West et al. (1991) claimed that people with traumatic brain injury (TBI) who had attended a supported work programme earned more than the programme costs after 58 weeks of supported employment. Furthermore, after two and a half years there was a net gain to the taxpayers who had ultimately funded the service. This did not include the indirect costs such as savings from family members who were able to return to work. Indirect costs have also been reported by Teasdale et al. (2009), who found that the strain on caregivers was reduced following use of a pager to remind patients what to do. Wood et al. (1999) wanted to establish the clinical and cost-effectiveness of a post-acute neurobehavioural community rehabilitation programme provided for 76 people surviving severe brain injury. The majority had sustained their injuries more than two years prior to admission and all had spent at least six months in rehabilitation. In terms of improved social outcomes and savings in care hours, it was found that the most cost-effective benefit was the provision of rehabilitation within two years of head injury; and it was still worthwhile, in terms of clinical and cost-effectiveness, to offer rehabilitation to those who were more than two years post-insult. Not only can rehabilitation save lives and improve quality of life for people with brain injury, it can also lead to major savings for government systems. It is estimated that people with moderate to severe brain injuries will have health and social care service costs of between £20,000 and £40,000 per year. A 25-year-old denied rehabilitation of the kind described in this book, and who lives to 75 years, may accrue costs of between £1,000,000 and £2,000,000.

There is plenty of evidence to show that comprehensive neuropsychological rehabilitation is clinically effective. Cicerone and his colleagues, for example, in a meta-analysis, found that such programmes can improve community integration, functional independence and productivity, even for patients who are many years post injury (Cicerone et al. , 2011). Van Heughten, Gregório and Wade (2012) looked at 95 randomised control trials carried out between 1980 and 2010 and concluded that there is a large body of evidence to support the efficacy of cognitive rehabilitation.

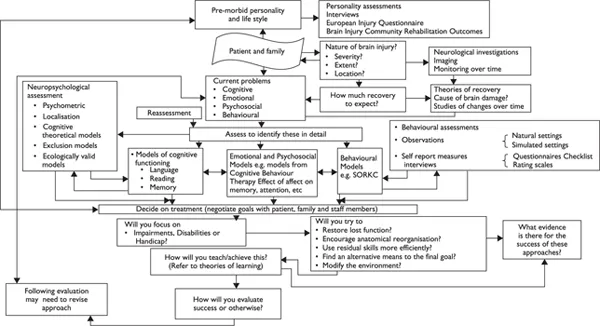

Rehabilitation for people with brain injury, conducted by qualified experts, is complex and demanding of expertise. It is not simply a tag on to medical treatment; neither is it in any way less complicated than analysing the results of MRI scans. We hope to show this in the following pages, and initially I would like to present a framework for rehabilitation that I developed a few years ago (Wilson, 2002) showing the areas that need to be considered and negotiated in order to provide effective treatment to brain injured individuals (see Figure 1.1). Obviously, not all areas will apply to each of the clients in this book. However, when contemplating each treatment described, the reader should be able to recognise particular pathways through the framework. At the end of this book we return to the framework to ask the reader whether we have kept to these pathways and been able to reach any kind of successful destinations as far as the clients are concerned.

The starting point for any rehabilitation programme is the patient or client and his or her family. In addition to background and ethnic and social issues, the nature, extent and severity of brain damage should be determined. Current problems, including cognitive, emotional, psycho-social and behavioural, need to be assessed. Models of language, reading, memory, executive functioning, attention and perception are available to

Figure 1.1 A model of Neuropsychological Rehabilitation (Wilson 2002, reproduced with permission of Taylor & Francis/Psychology Press).

provide detail about cognitive strengths and deficits. We can use assessment tools to determine emotional, behavioural, and social difficulties. Behavioural or functional assessments can be used to complement standardised assessment procedures.

Having identified problems, the rehabilitation programme can be planned. Patients, families, and staff need to negotiate meaningful, functionally relevant, and attainable goals. Ways to achieve these goals need to be formulated (for example through compensatory techniques or through particular learning strategies). Whichever method is selected, theories of learning need to be consulted, understood and applied where necessary. In Baddeley's words, ‘A theory of rehabilitation without a model of learning is a vehicle without an engine’ (Baddeley, 1993, p. 235). It is now accepted that social, emotional, and cognitive functions are interlinked and difficult to separate (Wilson, Gracey, Evans & Bateman, 2009), so we should be aware of models of therapeutic change such as therapeutic working alliance, or the client's experience of being understood, which optimise learning and engagement in rehabilitation. Recent theories of identity (Gracey & Ownsworth, 2008), Compassion Focused Therapy (CFT; Ashworth, Gracey & Gilbert, 2011) and Narrative Therapy (White & Epston, 1990) are some of the latest additions to our treatment approaches.

As part of the complete process of rehabilitation, our treatments or interventions must be evaluated. Whyte (1997) pointed out that outcome should be congruent with the level of intervention. If intervening at the impairment (body structure and process) level then outcome measures should be measures of impairment and so forth. As most rehabilitation is concerned with the improvement of social participation, outcome measures should reflect changes in this domain: for example, how well does someone who forgets to take medication now remember to take medication? We are continuously improving our evaluation of neuropsychological programmes but it is not easy. As Hart, Fann and Novack (2008) remind us, because of the great heterogeneity of patients receiving such rehabilitation and because of the variety of aims and methods required to achieve ultimate goals, the measurement of treatment effectiveness and final outcomes resulting from rehabilitation are difficult to evaluate (Hart et al., 2008).

When considering the model, it is not difficult to recognise the labyrinth of theories to be negotiated in order to design treatment that is appropriate for each brain injured individual with his or her particular needs. The same is true when considering the circumstances and needs of that person's family and even in some cases the wider community. We have made considerable progress in recent times (Cicerone et al., 2011) and are better at linking theory and practice (Wilson et al. , 2009) when designing practical solutions for the management of the brain injured person's daily life. These practical solutions are discussed in each chapter and supported by theoretical underpinning.

Despite considerable success, rehabilitation has to proceed with very limited resources. In some of the chapters, the survivors themselves comment on or allude to problems with funding. It is worth repeating once more that although rehabilitation for survivors of brain injury may seem to be expensive in the short term, it is cost effective in the long term. Given that most people who have survived an acquired brain injury and are referred for neuropsychological rehabilitation are young and will, on the whole, live a normal life span, they deserve to be given every chance to live as fulfilling a life as possible.

A major feature of the rehabilitation offered by the Oliver Zangwill team is its concentration on holistic treatment. A holistic approach to brain injury rehabilitation, ‘consists of well integrated interventions that exceed in scope, as well as in kind, those highly specific and circumscribed interventions which are usually subsumed under the term “cognitive remediation”’ (Ben-Yishay & Prigatano, 1990, p. 40). The holistic approach was pioneered by Diller (1976), Ben-Yishay (1978) and Prigatano (1986). Ben-Yishay and Prigatano (1990) provide a model of hierarchical stages in the holistic approach through which the patient must work in rehabilitation. These are, in order: engagement, awareness, mastery, control, acceptance and identity . The holistic approach argues that it is futile to separate the cognitive, social, emotional and functional aspects of brain injury. Given that how we feel emotionally affects how we think, remember, communicate and solve problems, and also influences how we behave, we need to acknowledge that these functions are inter-connected, often hard to separate and all need to be dealt with in rehabilitation. Holistic programmes offer both group and individual therapy to increase awareness, promote acceptance and understanding, provide cognitive remediation, develop compensatory skills and provide vocational counselling.

Holistic programmes, explicitly or implicitly, tend to work through hierarchical stages, as described by Ben-Yishay and Prigatano (1990), and are concerned with:

(i) increasing the individual's awareness of what has happened to him or to her;

(ii) increasing acceptance and understanding of what has happened;

(iii) the provision of strategies or techniques to reduce cognitive problems;

(iv) the development of compensatory skills;

(v) the provision of vocational counselling.

All holistic programmes include both group and individual therapy. It can be argued that the holistic approach is less of a model and more of a series of beliefs, or, as Prigatano (1999) puts it, a series of ‘Principles’. Nevertheless, it makes clinical sense and despite its apparent expense, in the long term it is probably cost-effective (Cope et al. , 1991; Mehlbye & Larsen, 1994; Wilson & Evans, 2002). In fact, there is mounting evidence that rehabilitation reduces the effect of cognitive, psychosocial and emotional problems, leading to greater independence on the part of the patient, reduction in family stress and eventual employability for many brain injured people (Cicerone et al. , 2005, 2011).

The programme at the Oliver Zangwill Centre (OZC) is based on these principles of holistic rehabilitation. Several chapters will refer to our assessment process and rehabilitation programme. Clients undergo assessment for programme suitability by attending the OZC for sessions with all team members that involve clinical interview, neuropsycholog-ical testing, mood assessment, family interview, community outings, functional tasks, participation in OZC meetings and lunch with current clients. Results are formulated as a poster that depicts the multiple contributions of personal and historic information, current context and the consequences of the injury on mood, cognition, communication and function.

The programme itself has evolved over time but essentially always includes attendance for 18 to 24 weeks with an intensive period devoted to psycho-education focused on themes including understanding brain injury, attention and memory, executive functions, communication and mood. Clients also learn and practise strategies dovetailed to their particular difficulties and receive individual psychological therapy to support them through the rehabilitation process. They then progress to the integration phase in which personal goals are developed and practised back in the client's own community. At present, clients attend the intensive phase for four days per week and the integration phase for two days per week, with follow up goal setting and reviews at three, six and twelve months post-discharge.

In their latest meta-a...