![]()

Part 1

Literacy, Learning and Drama

![]()

Introduction

This book aims to make literacy teaching an exciting and creative experience for both teachers and learners, whilst meeting National Curriculum and National Literacy Strategy (NLS) requirements. All the units of work have been tried and tested with children, teachers and trainee teachers. The units of work offered within this book are not intended as a complete drama curriculum or a complete literacy curriculum, but as a teacher's resource.

… it would be of value to many schools to have access to materials, ideas and strategies in the imaginative implementation of these strategies. (DfEE 1999: 79)

Many teachers lack confidence and expertise to plan drama-centred literacy units of work, even though they see the need for them. This is partly due to the lack of professional development opportunities and limited initial teacher education opportunities for this in recent years.

The structured units of work within this book are based upon the NLS range of required texts and use the drama activities, most commonly specified within the statutory English curriculum. The learning objectives for each unit are primarily taken from the NLS teaching objectives and from the Qualifications and Curriculum Authority (QCA) publication Teaching Speaking and Listening in Key Stages 1 and 2 (QCA 1999).

This book is in three sections. Part 1 gives the theory underpinning the practical use of process drama as a teaching and learning medium. It links it explicitly and contextually with current national strategies and curriculum requirements. It also links drama most importantly with the way recent research suggests children think and learn.

Part 2 contains a series of practical units which are linked directly to the requirements of the NLS. Each unit is planned to meet some of the requirements of the NLS for different year groups through the choice of text and the main teaching objectives. Additional objectives are drawn from those for speaking and listening published by the QCA in Teaching Speaking and Listening in Key Stages 1 and 2 (QCA 1999). Linked drama objectives are also made explicit. Each unit therefore is intended to provide a series of practical activities that link and integrate teaching and learning in multi-sensory ‘brain friendly’ ways, whilst meeting curriculum requirements.

Part 3 contains worksheets which can be photocopied and which extend and develop children's thinking in relation to specific activities within the units as well as reflectively consolidating their learning.

Each unit contains a wide range of drama strategies and activities, which enable teachers to select those most appropriate to their own teaching situation and purpose. Text-based activities are provided for children to create, perform and respond to moving and still images, sound and speech. Contextualised writing opportunities are devised from within and in parallel to the unfolding drama. Teachers can revisit these units, selecting different activities to support their teaching or repeat those successfully tried with other texts of their own choice.

Many teachers are concerned that the demands of the primary school curriculum have restricted the time they are able to give to the Arts and creativity in children's education. Approaches to the curriculum, which offer opportunities for both children and teachers to be creative are essential in providing rich, meaningful, and engaging learning environments. In many cases teachers feel that they have had inadequate training to meet this challenge, but it is possible for all practitioners to meet the current requirements and teach well, without losing opportunities for developing creativity and the Arts.

Indeed creative opportunities are embedded within the values, aims and purposes of the National Curriculum.

… the curriculum should enable pupils to think creatively … It should give them an opportunity to become creative. (DfEE/QCA 1999a: 1 1)

Education is now beginning to take account of recent research into the way the brain works and the ways in which children learn and to relate this to the teaching and learning of today's curriculum. The result is likely to be an increase in creative and multi-sensory approaches to teaching, linked to clearly defined learning objectives, which is what this book aims to provide.

We see great value in integrating the objectives of high standards of literacy with those of high standards of creative achievement and cultural experience. (DfEE 1999:79)

Many learners may require an emphasis on some Arts-based approaches and methodologies. Children have a range of preferred learning styles and it raises interesting equal opportunities and inclusion issues about curriculum access, if subjects are taught in a way that repeatedly disadvantage a certain gender or type of learner. With such emphasis on verbal and written learning, teachers could be alienating children rather than incorporating and involving them. Learning objectives are now well defined in all subjects and teachers need to be seeking the most learner friendly and effective way of realising them.

Starting from a realistic acceptance that the literacy objectives and the timetabled Literacy Hour remain fixed, there is still opportunity for creative teaching and learning through the Arts within the Literacy Hour and beyond. Drama, dance, music and art, all offer ways for children to respond to and express their individual and shared understanding of a text in ways that give opportunity for an energised, yet reflective, individual, group and class-collective response. Children need forms through which to explore and respond to text socially, emotionally, physically, morally, spiritually, culturally and cognitively. They need the opportunity to access text and express their developing understanding of texts, through art forms, involving the use and creation of visual images, movement and sound. Drama as a multi-sensory medium can provide an experiential structure for exploring text visually, auditorily and kinaesthetically. Its participatory nature motivates and promotes effective emotional learning, which is the most easily remembered learning, whilst at the same time providing intellectual stimulus.

OFSTED data on pupil response to learning indicates drama to be at the very top in motivating learning. (John Hertrich, HMI, OFSTED's Senior English HMI speaking at the NW Drama 3–8 Conference in January 1999 (DfEE 1999: 77))

Exploring texts through drama has long been accepted as a potent and successful teaching methodology. The imaginative framework drama provides, enables children to develop active, interactive and reflective relationships with the text whilst giving teachers the freedom to facilitate depth of learning in a diverse and exciting way.

The requirements of the National Curriculum for English are clearly defined and the framework of the NLS demanding. Catering for the diversity of children's learning and meeting these demands requires a creative and imaginative approach. Within both documents drama is both explicit and implicit. In the National Curriculum for English it is explicit as a strand of Speaking and Listening. It is implicit in all strands, i.e. Speaking, Listening, group discussion and interaction and Drama itself. Drama also spans the attainment targets of Reading and Writing, through its direct links with texts and playscripts. In the NLS, drama is again both explicit and implicit, within text level teaching objectives. Through drama, aspects of both sets of requirements can be easily integrated, enriching each other, and providing genuine and meaningful contexts for spoken, written and read language.

Participation in text level work through drama activities creates a sense of shared ownership through which children can investigate and develop characters, fill the gaps left in the text, reveal the subtext, and use their imaginations to bridge the divide between writer and reader, integrating and encompassing all aspects of literacy. Reading, writing, speaking and listening are interrelated activities and should be taught as such.

Teaching should ensure that work in speaking and listening, reading and writing is integrated. (DfEE/QCA 1999b)

Drama can actively integrate these aspects of English contributing to the broader concept of literacy which balances the focus between understanding and the development of skills.

Drama is a shared and co-operative activity which fires the individual and collective imagination. This can be channelled into forms of artistic expression, which may be written or spoken, individually or collectively expressed. Drama can provide these forms through which children's personal and interpersonal collective responses to literature can be explored and communicated. Its multi-sensory nature provides flexible structures to facilitate the abstracting, constructing, reconstructing and communicating of meaning. The mind, body and emotions are given opportunities to connect and function together rather than separately, enabling children to make all-round and interconnecting sense of their experiences and learning.

![]()

Drama and Imaginative Role-Play at the Foundation Stage | 1 |

The genesis of drama is in imaginative, dramatic play, and whilst this is evident throughout all the key stages, it is at the foundation stage that it is most apparent and prevalent. Indeed dramatic play is a natural developmental stage for children. Reluctance to play is usually an indicator of problems in other areas of development.

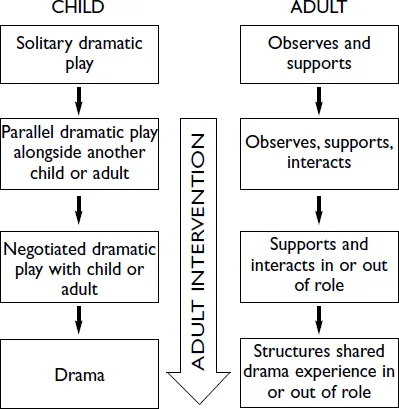

For children to be able to enter drama activities effectively they will need to already be able to play dramatically, to understand the notion of a make-believe world and to be able to communicate with others actively and verbally within that fictitious world. They will already, within their dramatic play, understand that objects can be used to represent other objects (e.g. a building block can be a piece of cake), and that it is possible to pretend that an object exists purely through mime. Once play moves beyond its initial solitary phase, parallel play alongside other children leads to interactive play with another child and negotiation develops. There is a point at which the child sees value in foregoing solitary play and compromising, in order to benefit from what other children or adults can bring to their own dramatic play (see Figure 1.1).

It is widely accepted that the pre-school child learns from the opportunity to role-play in imagined situations. In make-believe or dramatic play children are abstracting from their knowledge of the real world in order to establish for themselves a make-believe world within which they are empowered to operate and interact effectively. Much of their dramatic play involves re-enactment of the known and familiar. It remains important that young children entering the realms of the foundation stage and, later, the National Curriculum, do not lose the opportunity to play dramatically. Astute teachers, who are trained in the use of drama strategies will use dramatic play as a learning medium with which to deliver the curriculum. Furthermore, the elements of dramatic play and the unique imaginative framework, will remain ever present as drama lessons become a legitimised and educational ‘play’ forum. When a child is able to operate in abstract and imagined play-worlds with other children, the time is ripe for teachers and other empathetic adults to move in alongside the children, with a clear learning agenda. Adults can act as models for the pretending process and demonstrate how language, gesture and action can be appropriately used to explore and open up a variety of situations.

Figure 1.1 Opportunities for adult intervention in dramatic play.

As well as developing drama skills within the context of dramatic play, children are also involved in the conscious and subconscious learning of social rules, which apply to both dramatic play and drama. If teachers are introducing drama for the first time to young children, they may ask the children what is necessary for make-believe play to be successful with other children. What they say in response can be used as the rules of, or contract for, drama (e.g.‘we will support each other to make the drama work’).

The role-play area provides children with the opportunity to experiment with ideas from the real world in an imaginary setting. They can assume different roles both familiar and unfamiliar, use appropriate language and gesture and begin to develop their ability to empathise. They can enjoy the flimsy border separating fantasy and reality and may move easily between the two, although it is important that they are helped to understand that there is a distinction between the real and imagined world and they need to know in which world they are operating. The role-play area stimulates and encourages a creative response to situations, developing original and independent thinking, opening up avenues for expression, and the chance to pursue their learning in a multi-sensory environment.

Early literacy skills, laying the foundations for the broader concept of literacy, can thrive in the imaginative play area. There is a strong element of story-making and re-enacting within children's dramatic play, which is fundamental to story-drama and the future development of literacy. Structuring the play to achieve learning outcomes, and providing reading and writing materials in imaginary contexts, supports and promotes a literate, imaginative environment (e.g. the hospital corner may have a notepad by the phone to take messages). This allows the children to make connections between speaking, listening, reading and writing and begin to understand their purpose as conveyors of meaning. Within the safety of the imaginative setting, they gain in confidence and are helped to prepare and become ready for the more formal aspects of literacy.

The Curriculum Guidance for the Foundation Stage (DfEE/QCA 2000), is organised into six areas of learning and drama can make a significant contribution in all areas.

- personal, social and emotional development

- communication, language and literacy

- mathematical development

- knowledge and understanding of the world

- physical development

- creative development

Each area of learning within the guidance has listed opportunities that practitioners, including teachers, should acknowledge. Drama and role-play as a creative teaching and learning medium can be linked directly with, and across, all six areas.