![]()

1

THE ROMANTIC BALLET

La Sylphide, Giselle, Coppélia

The era of the Romantic ballet marks the beginning of women's ascendancy on the dance stage. Themes of the supernatural, exotic folklore, and the quest for the ideal were skillfully realized in the union of scenic effects, diaphanous costumes, shadowy gas lighting, and above all, the expressive use of dance technique, in particular the pointework and lightness of the female dancer, as well as the more earthy, often erotic styles of folkloric character dances. The first major Romantic ballet, La Sylphide (1832), according to dance historian Ivor Guest, “sealed the triumph of Romanticism in the field of ballet;” it was, he wrote, “as momentous a landmark in the chronicles of Romantic art as ‘The Raft of the “Medusa”’ and Hernani.”1 The ballet spawned a range of imitations and variations on the theme of the supernatural. It served as a template, ushering in a period, as the French critic Théophile Gautier remarked, when “the Opéra was given over to gnomes, undines, salamanders, elves, nixes, wilis, péris – to all that strange and mysterious folk who lend themselves so marvelously to the fantasies of the maîtres de ballet”2 And the relations in the ballets between humans and these fantastic creatures supplied stories that cast female sexuality and its regulation through the institution of marriage in a fresh light.

But it was not only the formal qualities or even the content of these ballets that set the tone of the Romantic era in ballet. The economic and social conditions of ballet production and reception in France had shifted after the 1830 revolution, for the Opéra was converted from a state-owned and -operated institution into a state-subsidized but privately run commercial enterprise. At the same time, the class make-up of the Opéra audience diversified, and the new, predominantly bourgeois, audiences – many of them raised on the phantasmic and exotic spectacles of Paris boulevard melodramas – exerted an unprecedented box-office power.3 In the 1830s and 1840s, the Romantic ballet flourished, especially in Paris, but also in other European capitals, including London, Milan, Vienna, St. Petersburg, and Copenhagen. And it brought to the international dance stage the anxieties and concerns of the bourgeois class – including those regarding women, their role in society, and their sexuality.

La Sylphide

La Sylphide, originally choreographed by Filippo Taglioni to music by Jean-Madeleine Schneitzhoeffer and given its premiere at the Paris Opéra in 1832, was a benchmark in ballet history, and it was also a turning-point in the career of Marie Taglioni, the choreographer's daughter and best student.4 For Taglioni fille created the tide role of the airy sprite who seduces a Scottish farmer away on his wedding day, into the mystical forest. The ballet showcased the dancer's mastery of technique, her special ability to mask the effort of physical virtuosity in order to appear suitably imponderable and ethereal. Gautier compared her to “an idealised form, a poetic personification, an opalescent mist seen against the green obscurity of an enchanted forest.”5 When she toured Russia in 1837, a critic marveled that “it is impossible to describe the suggestion she conveyed of aerial flight, the fluttering of wings, the soaring in the air, alighting on flowers, and gliding over the mirror-like surface of a river.”6 The role catapulted Taglioni to international stardom, and she became indelibly identified with the character of the Sylphide.

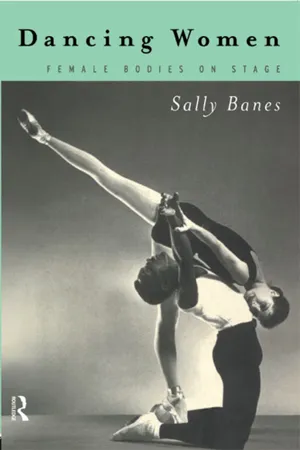

Plate 1 Marie Taglioni in La Sylphide, Paris (1837). Devéria lithograph, Edwin Binney 3rd collection, Harvard Theatre Collection, The Houghton Library. Courtesy of the Harvard Theatre Collection.

The scenario for La Sylphide was written by Adolphe Nourrit. A tenor at the Paris Opéra, Nourrit appeared in the leading male role in Meyerbeer's opera Robert le diable in 1831, playing opposite Marie Taglioni in a spectral Ballet of the [Dead] Nuns. For La Sylphide, Nourrit had been inspired by Charles Nodier's 1822 novella Trilby, ou le Latin d'Argail, set in an ancient Scottish landscape of lochs, mists, and highlands, in which a fisherman's wife falls in love – lethally – with a male elf.7 Nodier himself was influenced by Sir Walter Scott's fantastic evocations of a medieval Scotland populated by goblins, witches, and sorcerers.

Although Nourrit's scenario is often referred to as an adaptation of Nodier's story, it is also usually said that the two narratives have very little in common, besides the Scottish setting. For one thing, the gender relationships are reversed in La Sylphide. For another, La Sylphide makes no reference to religion, while Trilby involves an exorcism, a pilgrimage, and a ruined cemetery.8

What is not usually acknowledged is that the core theme of Nodier's novella – the fatal subversion of marital relations – becomes even more evident in the ballet. In fact, the transgender representation of the elf as a supernatural female figure in La Sylphide also recalls Scott's novels and poems, for both the Sylphide, as a seductive enchantress, and the witch, as a soothsayer with mysterious demonic powers, are reminiscent of Scott's women.9 The very structure of the choreography in La Sylphide emblematically narrates the regulation of marriage by the community. Indeed, if Trilby exacts 1,000 years of estrangement for infidelity, La Sylphide stands as a cautionary tale, admonishing men on pain of death to marry inside their own community and not to be lured outside their own folk into a world portrayed as Other and inhuman.10

La Sylphide, that is, is based upon a radical opposition of love and matrimony within the group – an event that is portrayed as occurring inside a cavernous farmhouse – versus love outside the folk – love literally outdoors, in the forest regions of the sylphs.11 Moreover, this difference is further presented as a choice between humanity (the folk), on the one side, and the inhuman (the Sylphide), on the other. Just as Taglioni herself and ballerinas in general might be seen as seductively drawing gentlemen away from their hearths and the heart of their families, and into the Foyer de la Danse, the Sylphide seduces young James away from his wedding into a realm that he barely understands and that he only inhabits at the cost of self-destruction.12

In 1834, the Danish choreographer August Bournonville saw Taglioni's Sylphide in Paris. He created his own version in 1836 in Copenhagen, to new music by Hermann Løvenskjold. It is Bournonville's version that I will analyze here, because I believe that, although it has been altered in obvious ways over the years, it is still the closest we can come to the original Taglioni version.

La Sylphide is a ballet in two acts. The first act takes place in a commodious farmhouse where James Reuben lives with his widowed mother. It is his wedding or betrothal day.13 But just before the entrance of Effie, his fiancée, and the wedding guests, James, dozing by the fireplace, is visited by a gossamer vision – the Sylphide.14 She hovers over his chair, dances out her love for him, kisses him, and then, when he wakes and approaches her, disappears up the chimney. Gurn – James's friend and rival – arrives, then the bride, with her women friends. When James notices Madge, the witch, warming herself at the fireplace, he angrily tells her to leave. But she offers to read the eager young women's futures in their palms. Notably, considering the major theme of La Sylphide, all of Madge's predictions concern marriage and procreation: the first young woman, Madge predicts through pantomime, will bear many children who will all flourish; the second, children who will die. The third fortune-seeker is a child, who is slapped for her effrontery: she is too young for such stories. The fourth young maiden is surprised to discover (she mimes embarrassment as she touches her abdomen) that she is already pregnant. Madge tells Effie, the fifth maiden, that her happiness lies with Gurn, not James – a shocking revelation. Marriage stories, it seems, preoccupy the women in this ballet.

Effie goes upstairs to get ready for the wedding ceremony; the guests leave, and suddenly the Sylphide appears again, this time in the window. She tells James she loves him and dances with him flirtatiously. She wraps his scarf around herself and seems to beg for his protection. Gurn watches as James kisses the sprite. When it is time for the others to return, the Sylphide hides in James's armchair, and he covers her with a plaid. Gurn tells the others what he has witnessed and pulls the plaid aside, but the Sylphide is gone. All that remains is a bundled scarf. The rest of the guests arrive and dance in various formations, as the Sylphide, visible only to James, flits among them. As the bridal couple is about to exchange rings, the Sylphide snatches Effie's ring from James's hand and dashes out of the house. He runs after her, leaving the wedding guests stunned.

The second act takes place in a misty forest. Madge summons the other witches, who dance around a boiling cauldron, out of which Madge pulls a scarf. The mist clears, and the Sylphide and James appear. She shows him how she lives and introduces him to a bevy of other sylphs. But as they dance together, she constantly escapes his grasp. James seeks advice from Madge, who gives him the scarf and advises him to wrap it around the Sylphide. This, she explains, will make the Sylphide's wings fall off. But when he captures her, the loss of the Sylphide's wings also marks her death. The sylphs carry her aloft, while the wedding procession of Effie and Gurn crosses the stage. As James falls to the ground, grief-stricken, the witch rises over him triumphantly.15

Commentators have often interpreted La Sylphide as an allegory of the search for the ideal, as represented by the Sylphide.16 And such an interpretation is surely borne out in the searching, yearning movements of James, who is so often late in arrival, the sylph having fluttered elsewhere. Yet, it seems that there is also a darker design that is compatible with the incidents of the ballet. It is the story of marriage, of socially licensed sexuality, and of what is possible and impossible, sanctioned and forbidden, with respect to courtship.17

The theme of whom one may marry, of course, is a recurring one in Romantic ballet, although it emerges as early as the Pre-Romantic ballet La Fille Mal Gardée (1789). It appears, for example, in the major works like Ondine, Alma, and Giselle, as well as in La Sylphide. In Giselle, the theme of whom one may not marry is portrayed most realistically and straightforwardly. One must stick with one's own social class or risk destruction. In La Sylphide, perhaps the sylphs represent an aristocratic station to which James ought not aspire. They are certainly higher than he, considering their aerial capabilities (not new to this ballet, but nevertheless symbolically potent here). In any case, they, along with the tribe of witches, stand for the Other, for some literally alien group outside what is given as James's natural and appropriate network of affections – so often portrayed as a ring of joyous, folkish dancers.

Within the farmhouse, James is surrounded by his people. And the ballet literalizes the ethnocentric proclivities of peoples to identify themselves as the People and, in consequence, to regard outsiders as not quite human, or, in the case of La Sylphide, as downright inhuman – as bewinged creatures sometimes marked by insectile movement and even more generally by “unnatural” movement (i.e., balletic movement which, parenthetically, also connotes aristocratic movement).18 The action of the ballet, in turn, mobilizes this association of the inside/human/folk in order to cast marriage to outsiders and nonfolk – to sylphs, foreigners, and other nonhumans – as destined to go badly.

So, in terms of its plot, La Sylphide is fundamentally about whom one should marry and whom one shouldn't. But it advances this theme in its very structure, not simply in its plot. Symbolically, the ballet presents two options: marriage inside the group, which is depicted as human and as sanguine, and marriage or love outside, which is portrayed as union with the inhuman and as inevitably tragic. In short, freely borrowing from Lévi-Strauss, one might say that La Sylphide is a myth about the regulation of marriage – i.e., it is about whom it is appropriate to marry. Working out the inappropriateness of marrying one of them instead of one of us – the inhuman rather than a human; the Other rather than a member of the community – not only supplies the thematic motivation for the plot development in La Sylphide. It also serves as the basis for the articulation of an overarching choreographic structure of studied and highly connotative contrasts. This is developed in terms of contrasts between the endogamous marriage – within the population of Scots – and the exogamous marriage – between a Scot and a sylph.

In order to analyze the choreographic structure, it will be useful first to discuss the movement structures for the three salient groups in the ballet (the Scots, the witches, and the sylphs). Then I will analyze the choreography for the key individuals (the Sylphide, Effie, James, and Madge) and for their interactions.

In terms of the myth of marriage regulation, the audience is presented with three “tribes,” only one of which it is appropriate for humans to marry into, since of the three groups only one is human. Although they have aspects and even steps in common, each of these tribes is marked off by distinctive movement qualities. Even if a particular gesture or step is replicated from one group to another, it does not always have the same look or significance. The same step may be performed in disparate styles, taking on an entirely discrete identity (for instance, both Effie and the Sylphide do rondes de jambes en l'air, but in one case this signals precision and closure, while in the other it suggests weighdessness and porosity). Or, it may be clear that a member of one group is “quoting” the movement as well as the style of another group (as when Gurn flaps his arms and then poses à la Sylphide to show the Scots what he has seen, i.e., the Sylphide; or when, in the forest, the Sylphide gestures in the Highland Fling shape and style similar to that seen among the Scots in Act I – right arm held shoulder height, left arm curved solidly over the head – to signal to James her desire to marry him and her willingness to join his clan).

The initial group, the Scots, have two dances in Act I: first, there is the entry of Effie's women friends, and then a dance of the whole community, including both males and females. Each dance is done in a distinctive folkdance style, with allusions to such Scottish dances as the Highland Fling. The women's dance is a brief, brisk ceremonial entry. Two phalanxes of four young women, led by a ninth female dancer, hold their left arms jauntily akimbo in the style we soon come to recognize as characteristic of the Scots. Their right arms, however, hold either the hems of their kilts (suggesting a curtsey) or a gift. They nod their heads or turn them smartly on the beat of the music, and they kick their feet forward as they step, like frisky colts. After the fortune-telling episode and the pas de deux between James and the Sylphide, the women enter in the same formation as bef...