The Ritz, Paris

Looking to eighteenth-century France through the lens of nineteenth-century historicism for a twentieth-century hotel lobby

Mark Hinchman

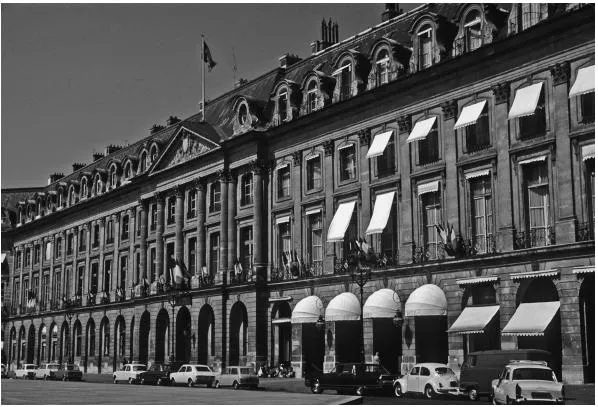

1 Façade, Place Vendôme, built in 1688

A precocious Londoner, Arthur Joseph Davis (1878–1951), went to Paris to study architecture at the École des Beaux Arts at the age of sixteen.1 Within a few years of his arrival, he worked on a project, the Ritz Paris, that ushered in a new era of hotel design. The project also marked the beginning of his partnership with the French Alsatian architect, Charles Mewès (1858–1914). Davis studied with Godefroy before finding his place in Pascal’s atelier at the École. While he was a student, an established architect active in Paris, Charles Mewès, sought Davis’s assistance on a competition for the 1900 Paris Exhibition. Their entry took fourth place, but their collaboration marked the beginning of a successful architectural partnership. The resulting firm, Mewès and Davis, was active up to the eve of the Second World War and catered for an impressive and international roster of clients.

One of the first was César Ritz, who asked Mewès to help him fashion a hotel from multiple adjacent properties on the prominent site of one of Paris’s grand public spaces, the Place Vendôme. Hence, the Ritz Hotel was carved out of existing buildings. Jules Hardouin Mansart initially designed the urban space and the façades of the Place, which dates back to 1688. The site is resolutely urban where it meets the Place, and yet a garden provides greenery at the rear of the property. Ritz’s charge to Mewès and his young assistant was to remodel the site into a first-class hotel. The collaboration of the Swiss hotelier, his chef, Auguste Escoffier, and his architect has taken on apocryphal proportions.2

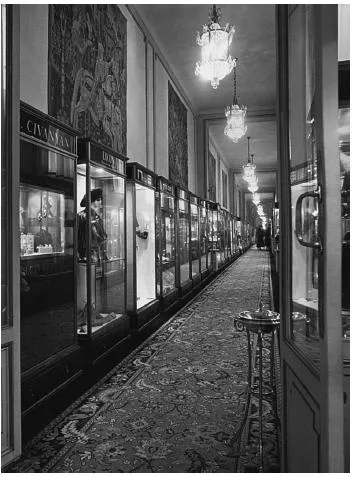

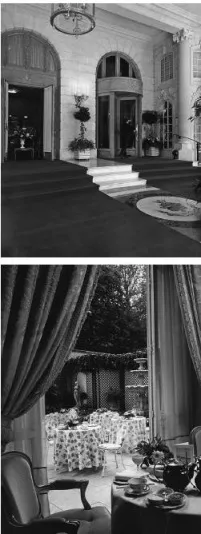

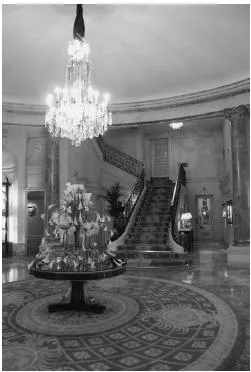

2 (top left) Entry, Ritz Paris, 1900 3 (bottom left) View onto garden, Ritz Paris, 1900 4 (right) Ground floor circulation, Ritz Paris, 1900

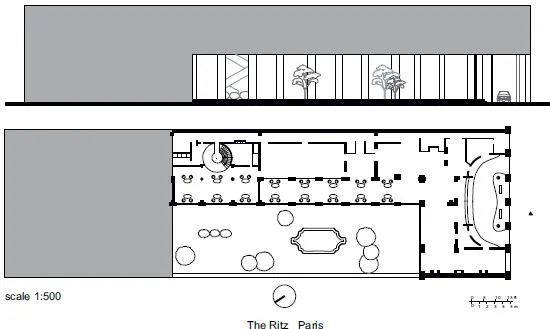

The plan of the Ritz Paris relies on an L-shape circulation as its spine, with the short leg of the L constituting the façade on the Place Vendôme, and the longer leg extending backwards, towards the rear of the building. From this horizontal circulation, grand spaces, interior and exterior, extend on both sides. The circulation space itself is generous, classically detailed and furnished so that it functions as part of the suite of opulent public spaces. The lobby of the Ritz Paris is not a single room, but a space that flows from room to room. At multiple locations, what separates one room from another is a level change, indicated by two stairs and further delineated with a pair of columns. The firm used this composite feature repeatedly in their projects.

5 Entry hall, Ritz Paris, 1900 6 Stairway and reception, Ritz Paris, 1900

As famous as the lobby is the fact that diners at Escoffier’s restaurant ordered their meals à la carte. In their plans, Mewès and Davis employed circles and ovals in two ways. One was as a central distribution point, the node from which axes radiated.Another was hierarchically to emphasize the most important rooms, such as L’Espadon Restaurant. The hotel’s other innovation was that the lobby’s restrained classicism signified that this was the sort of establishment with en suite bath and dressing rooms. The Ritz lobby is mostly made of plaster, with stone decorative work and carpeted floors. The careful attention to the plasterwork, painting and gilding made a cohesive project out of what was essentially painted plaster with a judicious use of expensive materials.3 The rooms were completed with reproduction Louis XV and Louis XVI furniture painted to match the walls, in pale yellow, gray, or pink.

For all its influence, the Ritz Paris is a surprisingly small hotel, with a big influence. The hotels that followed it were larger, but with the Ritz Paris, all the essential architectural elements that the firm relied on for decades were in place. An article written in 1947 explored at length the impact of the Ritz Paris on twentieth-century hotel design: “this small but exclusive hotel soon became the model for all subsequent buildings of its type.”4 Most observers commented on the architectural precision of the designs of Mewès and Davis, an effect achieved through the on-hands efforts of both partners. In the tradition of the beaux arts, they created watercolor washes; when construction was underway, the architects resolved many details with full-scale drawings.5

It is interesting that the eminent architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner describes two of their later London projects as “urbane Italian Renaissance manner that derived from the American firm Mead, McKim, & White” (sic).6 Alastair Service, who writes approvingly of the firm’s work, states that “they did produce a lot of the most elegant and visually enriching street architecture of London and other cities, as well as some joyous interiors.”

The Ritz lobby represents a strand of twentieth-century design that is antithetical to modernism. Mewès and Davis were fully aware of these innovations and pointedly ignored them. Decades after the debut of the Ritz, when Davis enjoyed an eminent position in London’s architectural community, one Lord Clonmore explicitly criticized, in print, the hospitality work of the firm. The subject was ocean-liner interiors, a sector of design work the firm excelled in, largely owing to the success of the Ritz hotels. Davis was considered an expert on the subject and had previously written about the same topic.7 Clonmore wrote:

The modern vessel is a lovely thing. But go inside one of our “luxury ships”, get over the excitement of traveling, of that particular thrill when the train first reaches the docks, and wander carefully through its “social halls” and “winter gardens”. You will be very depressed. If not, you have the kind of taste which admires the new London hotels.8

7 Lobby and stair, Ritz Madrid, 1910 8 Façade bay, Ritz London, Piccadilly, 1903

A characteristic of ocean liners and hotels alike is that their reputation derives as much from their guests as their interiors and furnishings. No hotel in the world has a roster of former guests to rival that of the Ritz Paris. The list of twentieth-century visitors includes Charlie Chaplin, Marlene Dietrich, Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall, Barbara Hutton, Randolph Churchill, the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, and Richard Nixon.9 The twenty-first-century list includes luminaries from David Beckham to Mark Wahlberg. But no doubt the most famous guest whose history is linked to the Paris hotel was Diana, Princess of Wales, who was dating the owner’s son Dodi Al-Fayed, and whose final moments a security video caught as she exited through a revolving door, moments before her death: an incursion of popular culture into an environment designed to high academic standards.10

The success of the Ritz Paris led César Ritz to hire Mewès and Davis to remodel the Carlton Hotel (1901) in London, which in turn led to a new, ground-up hotel, the Ritz Piccadilly (1903), all of which are further elaborations on the Ritz design schema. The English hotels were followed in turn by hotels in Spain, the Ritz Madrid (1910) and the Hotel Maria Christina (1912) in San Sebastian, and ocean-liner interiors for Germany’s Hamburg–America Line and Britain’s Cunard. The design elements so successfully put into play at the Ritz Paris, 1900, came to constitute what the public expected of a first-class hotel. Subsequent hotels by the firm and their imitators employed a similar design approach. A phrase that dismissively describes their design schema as “ tous les Louis ” contains a kernel of truth: behind baroque façades, Mewès and Davis cleverly inserted eighteenth-century French classical interiors for a commercial venture that an enthusiastic twentieth-century public embraced.

9 Lobby, Hotel Maria Christina, San Sebastian, 1912

10 Section and floor plan, Ritz Paris

Notes

1 Obituary, “Arthur Davis,” The Times, July 23, 1951.

2 About Davis’s years in Paris, Alastair Service writes: “The start of his career is something of a fairy story come true.” Service, Alastair et al.: Edwardian Architecture and Its Origins, London: Architectural Press, 1975, p. 435.

3 Their requirements for plasterwork and painting are delineated in detail in the specifications for the Royal Automobile Club. Mewès and Davis: Specification of Works Required to be Done and Materials to be Used in the Erection and Completion of New Club Premises Pall Mall, s.w. for the Directors of the Royal Automobile Club Buildings Company Limited (London: Mewès & Davis and E. Keynes Purchase, September 1909. MeC/1–2).

4 ‘The creator of the modern luxury hotel: Charles Mewès, Architect, 1860–1914’, RIBA Journal, October 1947: p. 604.

5 Reilly, C. H.: “Eminent living architects and their work: Arthur J. Davis, FRIBA,” Building, April 1929, p. 158.

6 Bradley, Simon and Pevsner, Nikolaus: London I: The City of London, Buildings of England series, London: Penguin, 1997, p. 123.

7 Davis wrote two articles on the topic. Davis, Arthur: ‘The Architecture of the Liner: Planning, Decoration and Equipment’, The Architectural Review, 35, April 1914: p. 89; and ‘The Decoration of Ocean Liners’, Journal of the Royal Institute of British Architects, 1922: p. 230.

8 Lord Clonmore: ‘The architecture of the liner’, The Architectural Review, LXX, July–December 1931: p. 62.

9 Boxer, Mark (Ed.): The Paris Ritz, London: Thames and Hudson, 1991, p. 12.

10 Mohamed Al-Fayed is the current owner and was responsible for a thorough renovation of the hotel that was in keeping with the design direction established by Mewès and Davis.

Sources

‘The creator of the modern luxury hotel: Charles Mewès, Architect, 1860–1914’, RIBA Journal, October 1947: 603–4.

Binney, M.: The Ritz Hotel, London, Foreword by the Prince of Wales, London: Thames & Hudson, 2006.

Boxer, M. (Ed.): The Paris Ritz, Introduction by Pierre Salinger, London: Thames & Hudson, 1991.

Bradley, S. and Pevsner, N.: London I: The City of London, The Buildings of England Series, London: Penguin, 1997.

Montgomery-Massingberd, H. and Watkin, D.: The London Ritz...