- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Population Movements and the Third World

About this book

The interrelationship between migration and development is complex. The causes of migration stem from the uneveness of the development process and the effects exert a powerful influence on the pattern and process of development. This volume explores both the concepts and facts behind the main forms of population movement in the third world today, particularly rural-urban migration. Examining the causes and consequences of migration, the author assesses the implications for planning and policy-makers.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

NaturwissenschaftenSubtopic

Geographie1

Introduction

Between a rock and a hard place?

‘Between a rock and a hard place’ is one of several aphorisms which was used to characterize the plight of the half-million or so Asian and North African refugees who fled to Jordan from Kuwait and Iraq with the onset of the Gulf Crisis in late 1990. It aptly described the paradoxical situation whereby huge numbers of people seeking refuge from potential conflict found themselves faced with desperate conditions in hastily constructed refugee camps until the international relief operation creaked into action. Whilst the world’s attention and sympathy was momentarily drawn to their plight, few people may be aware that these economic migrants-turned-refugees have continued to suffer the aftershocks of the Gulf War long after the cessation of hostilities. Having returned to their countries of origin with next to nothing, their lucrative work contracts terminated, most face very bleak prospects of finding gainful employment back home. Many are saddled with huge debts incurred in financing their sojourn in the Middle East. Somewhat ironically, the reconstruction programme following the devastation of the Gulf War offers their best chance of recouping their losses.

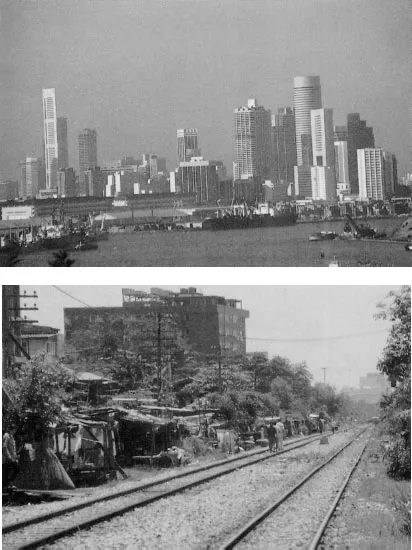

A key aspect of many forms of population movement in the Third World is that they offer the tantalizing chance of better prospects elsewhere, but that these very often fail to materialize in reality. Occasional references appear in the migration literature to the perception of a ‘promised land’ in the mind’s eye of emigrants to the industrialized West, and the expectation amongst rural migrants that the streets of their capital cities, metaphorically, will be ‘paved with gold’. The reality is often quite different. Immigrants may be seen and treated as second class citizens by the host society, and may have great difficulty in obtaining well-paid employment and in adjusting socially and psychologically to their move. The ubiquitous shanty towns, and the frequent images of people scavenging and otherwise scraping a living in the major urban centres of the Third World are further testament to the chasm which sometimes separates expectation from reality for many city-bound migrants from the countryside.

Plates 1.1 and 1.2 Image and reality: an illustration of the two extremes of life in the Third World city. The modern, high-rise environment may attract migrants to urban areas but many struggle to obtain an acceptable standard of living

Whatever its outcome, however, it is hard to overstate the importance of mobility to the peoples of the Third World. The ability to move from one place to another, be it to escape the effects of environmental disasters or to exploit opportunities which may be available elsewhere, represents an essential means of dealing with the problems which beset many who live in the world’s poorer countries. Migration from village to city may constitute a ‘pressure valve’ whereby people may escape the drudgery and uncertainty of rural life. Flight across international frontiers may, as a last resort, represent the only means by which the persecuted, the frightened and the neglected can escape warfare or the brutality of the tyrannical regimes which litter the developing world. The periodic movement of farmers and pastoralists may enable them to overcome environmental constraints on their livelihood.

On a global scale, the movement and interaction of people has, historically, been an important factor in world civilization, in the enrichment of cultures and in the spread of technology; migration representing ‘an integral and vital part of human development’ (Bilsborrow, et al., 1984: 2). Migration has also played an important role in the processes of industrialization and urbanization, initially in Western Europe and more recently in many other parts of the globe. Conversely, migration has also provided the cornerstone of some of the less positive chapters in human history, such as the slave trade between Africa and the Americas, and forced labour in support of the economic exploitation of colonial territories.

Whatever the historical and contemporary importance of population mobility, we must not lose sight of the fact that not everyone is ‘mobile’ to the same extent. The wealthy and well-connected may be in a position to use their movement to another place as a means of enhancing their present circumstances and status. Others have little choice, and must make do as best they can upon arrival in a new location. Others still may not even have the option of movement, perhaps because they cannot afford to leave, or they know nothing about places and opportunities outside the confines of their home area, or possibly because of social and cultural ties which bind them to their place of origin. This latter group of people – those who lack mobility, for whatever reason – must thus endure conditions in their home areas as best they can. Many, of course, have no desire to leave in the first place.

If we consider that there are huge numbers of people in Third World countries who have been displaced from their home areas, either voluntarily or involuntarily, and that there are maybe several times as many who, given the choice, might prefer (particularly on economic grounds) to be somewhere else, we must ask the question ‘why?’. There is no simple answer, but it is reasonable to suggest that the contemporary scale of population movements in the Third World, both actual and latent, may be attributed in part to one or more of the following factors:

1 The failure of the process of economic growth to bring about an even pattern of development in which all areas, sectors and groups of people have shared to a more or less equal extent. The fact that the predominant direction of movement tends to be from economically depressed areas where opportunities for advancement (or even survival) are very limited, to economically dynamic locations where opportunities are perceived to be plentiful, suggests a close association between the unevenness of the development process and the incidence of population movements (especially migration). In this sense, we might consider the incidence of migration to represent the ‘litmus test’ of unsuccessful development.

As we shall see in Chapter 4, some people may be displaced from their home areas by sheer poverty and lack of opportunity, whereas others may choose to leave because they perceive that their aspirations are more likely to be satisfied somewhere other than their local area. The word ‘perceive’ is used advisedly here: quite often media such as television, radio, newspapers and advertising are responsible for raising people’s awareness of life outside the narrow confines of their home area to the extent that it heightens their level of dissatisfaction with their present conditions and may make them more prone to migration. The image created by the media may present a biased or distorted view by building up certain positive characteristics and playing down others.

2 The penetration of the market economy has also strongly underpinned the movement of people within Third World countries. Cash has replaced barter as the main medium of exchange in most parts of the Third World, and now perhaps the majority of households have need of cash to purchase goods and services which previously they may have provided for themselves. Out-migration to seek paid employment may represent the best (and in some instances the only) means of obtaining an income with which to satisfy these growing cash needs and people’s rising aspirations with regard to preferred standards of living.

The operation of a land market, and the growing tendency for land to be seen as a commodity rather than a communal resource, has also provided the opportunity for wealthy and powerful people to accumulate vast land-holdings, and for others to dispose of their land for reasons of debt, illness or labour shortages. The associated phenomenon of landlessness, and the weak position of the land-poor vis-à-vis the land-rich, has also provided a strong source of momentum for the movement of people away from their home communities.

3 The processes of modernization and social change have also been important in underpinning the growth of population movements in many Third World countries, although in this case it is rather difficult to isolate cause from effect. It is really only over the last two decades or so that a number of traditional constraints on mobility, particularly those restricting the migration of young women, have started to break down with the effect that, as we shall see in Chapters 4 and 5, migration flows in several countries now consist predominantly of female migrants. It might be argued, however, that migration has itself been partly responsible for breaking down the barriers to female migration (such as culturally prescribed gender roles, or religious constraints on the participation of women in the workforce), as it has helped to raise levels of awareness about opportunities for employment elsewhere, and may also have engendered a greater level of individualism which in turn may have weakened the strength of community or parental control over the actions and decisions of young women. In several of the rapidly industrializing countries of Asia and Latin America, the rising range and number of factory jobs suitable for women may also have stimulated a growth in the incidence of female migration. Where this has occurred without a parallel process of social change, rising levels of friction and social tension in source communities may have resulted.

In many countries, education has proven a powerful instrument of social change whilst, at the same time, having the effect of raising people’s qualifications and expectations beyond the capacity of their home areas to accommodate. Out-migration has very often been the inevitable result.

4 The rapid pace of population growth in many Third World countries provides further momentum to the rate of population movement, although in the majority of cases the impact is largely indirect. Thus out-migration from rural areas has often resulted from a failure or inability to accommodate population growth by expanding the cultivated area or intensifying agricultural practices. Even more alarming is the tendency for people to be displaced from the land by various forms of agricultural modernization (mechanization in particular) or through the encroachment of other forms of economic activity (commercial logging has had a severe effect on shifting cultivators in many parts of South-East Asia, for instance), when demographic conditions possibly determine that more people should be being absorbed by agriculture. The limited development and diversification of the non-farm economy may also determine that there are few employment opportunities locally which might absorb a steadily growing workforce, providing further incentive for people to move to seek their livelihood elsewhere.

5 We also find that population growth may have pushed land-hungry people into fairly marginal ecological zones such as infertile uplands, riverine areas which may be prone to flooding, or arid zones which may face prolonged periods of drought. Here it is much more difficult for people to eke out a living, and thus people may be forced into quite frequent movement simply to safeguard their economic and nutritional survival. Not infrequently, these marginal ecological zones are much more prone to natural disasters which may also result in the periodic displacement of substantial numbers of people (contemporary problems in the Horn of Africa and Bangladesh are an obvious illustration of this phenomenon).

6 People may also have to leave their homes to make way for infra-structural projects such as reservoirs, ports, roads, air terminals, and so on. In such cases the interests of the communities which are affected by these projects are usually seen as inferior to the broader national or strategic interests which may be associated with the projects’ construction. None the less, the government or construction agency usually takes some degree of responsibility for the resettlement of the displaced people.

7 Finally, people throughout the Third World have been displaced from their home areas by various forms of persecution and strife. This may take the form of warfare between neighbouring countries or a civil war between rival factions; inter-ethnic or inter-religious conflicts which, in some cases may themselves have resulted from the historical movement of one group of people into the territory of another; or local disputes between individuals, families or small groups of people with others within their home communities. The nature of the political regime which governs the country may also make the position of certain groups of people in their home societies untenable. Whatever the precise reasons for the conflict, the movement of sometimes quite large numbers of people to a new location may be the only viable alternative to discomfort, danger or even death.

Whilst the movement of population may thus been seen as an essential ‘release valve’ for many of the Third World’s contemporary problems, developmental or otherwise, it does not inevitably follow that the act of movement will lead to an improvement in the mover’s predicament or prospects. Thus, many who use migration as a means of escaping poverty may find that their movement brings only a change in location, not circumstance. This is especially true of people who, although their movement may be definitionally ‘voluntary’, are in reality faced with no alternative since remaining in situ is not a realistic option. These people may have little if anything to offer and, in reality, little to gain from their movement. Even those whose departure may be entirely voluntary may fare little better from their move to a new location. This may be in part because, due to the distorted image of other places which is created by the media or which is conveyed by returning migrants, their perception of life and opportunities in the chosen destination may be quite widely divorced from reality. Thus the expectations which may have underpinned the decision to move may not be fully realized.

Refugees and other displaced peoples may similarly substitute one set of difficulties for another. Although they may have succeeded in attaining refuge or respite from whatever problems they may have been experiencing, they may encounter significant barriers to their smooth and successful settlement in another place, especially if there is resentment amongst the local population to their presence. Increasingly we find also a growing reluctance amongst governments and agencies to accept refugees, given partly the sheer scale of population displacement in many parts of the world (Cambodia and Mozambique, for example), and also the apparently growing tendency amongst ‘refugees’ to use the seeking of political asylum as a cover for the pursuit of better economic prospects in a second country. This very thin and difficult definitional distinction between political refugee and economic opportunist has, as we shall see in Chapter 2, controversially been used as a formidable barrier to the resettlement of Vietnamese refugees from countries of first asylum, and also a justification for their involuntary repatriation to Vietnam.

It might therefore seem somewhat illogical that people should continue to move from their home communities when, for many, their circumstances in the chosen destination may appear to be no better, and frequently much worse, than those they left behind. And yet the scale of movement would appear to be increasing. This apparent paradox may be explained by three main factors. First, a large number of movers do of course benefit substantially from their move to a new location. The fact that there are potential benefits to be derived from movement thus does little to deter others from seeking to avail themselves of these benefits. Second, in reality many people have little choice but to move, and thus can only hope that their movement elsewhere may lead to a change in circumstances. Unhappily, for many this does not materialize. Finally, there is the question of time-scale. It is generally true, particularly in the case of rural–urban migration and emigration, that people’s longer-term prospects may be rather better in their new location than in their place of origin. Thus migrants to the major urban centres of the Third World can reasonably expect their children’s prospects, if not their own, for a better education, higher-paid employment and a more satisfactory living environment to be better in the city than the countryside.

If we accept that, in the short term at least, the movement of population does not automatically remedy the problems which cause people to leave their home areas, we need also to consider what effects population movement has on the broader social, structural and spatial problems which characterize a great many Third World countries. In other words, does the movement of population in general represent anything more than a basic ‘survival strategy’ for the people involved, or does it contribute to a process whereby the longer-term prospects for development will be better than before?

It is this question which provides one of the central themes for discussion in this book. There is, of course, no simple answer. This is partly because the term ‘population movements’ encompasses such a wide range of forms of mobility, which occur in response to a wide and diverse range of factors, and which have such a variable and inconsistent range of effects. Thus, any attempt at generalization and simplification would be dangerously misleading. Several analysts have suggested that, o...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of plates

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Preface

- 1 Introduction

- 2 A typology of population movements in the Third World

- 3 Forms of population movement in the Third World

- 4 Why people move

- 5 The effects of migration

- 6 Population movements in the Third World: policy and planning issues

- Review questions and further reading

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Population Movements and the Third World by Mike Parnwell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Naturwissenschaften & Geographie. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.