This is a test

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Englishness and National Culture

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

In this highly engaging book, Antony Easthope examines 'Englishness' as a form and a series of shared discourses. Discussing the subject of 'nation' - a growing area in literary and cultural studies - Easthope offers polemical arguments written in a lively and accessible style. Englishness and National Culture asserts a profound and unacknowledged continuity between the seventeenth century and today. It argues that contemporary journalists, historians, novelists, poets and comedians continue to speak through the voice of a long-standing empiricist tradition.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Englishness and National Culture by Antony Easthorpe in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Popular Culture in Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I: NATION

1: NATION, IDENTITY, DISCOURSE

I am determined to talk about France as if it were another country, another fatherland, another nation.

(Fernand Braudel 1988, l, p. 15)

Britain…treated as if it were a foreign country.

(Gregory Elliott 1995, p. 7)

National identity is a product of modernity. It is therefore comparable to another exemplary version of the modern experience though one that rarely gets serious attention: driving a car.

The one thing everybody says about driving is that you don’t learn how to do it until after you’ve passed your test. You know how to drive when it has become a habit, a pre-conscious integration of perception and movement. Without reflection, from the whole field of vision I immediately pick out the signs that matter (that car’s flashing light 50 metres away means it is turning left) and co-ordinate them with motor response (foot off accelerator and over brake). Driving is a matter of submitting to rules, something you are reminded of every time you approach a crossroads (are the lights red or green?).

Driving offers us two radically different positions. In one I have exceptional individual mastery. I see the world with almost all-round vision through a wide-screen windscreen as well as via two side-view mirrors and one rear-view mirror. Besides physical controls (operated with minimum physical exertion) I have ready access to a display of dials, gauges and one-touch switches. Driving seems an almost spontaneous extension of my bodily self—I inhabit it, I live it, it is a disposition so effectively assimilated that I say ‘I drive’, ignoring the car I do the driving with.

On the other hand, although notorious as ‘private, enclosed’ and ‘individual’ (Williams 1975, p. 356), car driving is a stunning instance of the dependence of the self on other people. To drive means that every micro-second I consign my life to the rationality, competence and good intentions of the Other. I have to trust that they will read the signs, obey the rules and observe the conventions as much as they trust I will do the same, checking the mirror before pulling out, stopping at red lights, and so on. To do it at all I have to believe I’m driving the car but it is as true to say that the car and the roadway system drive me.

A car driver, then, has a self he or she knows about yet that depends on another identity in which they are situated and positioned in ways they know little about. This book will explore national identity not as a set of images, figures and practices of which we are more or less conscious but rather as an unconscious structure. It is, in a sense, a postcolonial study of Englishness. While various Brits have been happy to write about other countries and cultures in the context of post-colonial theory, few such dispassionate eyes have been turned on the motherland. I shall try to write about English culture as if it were foreign to me.

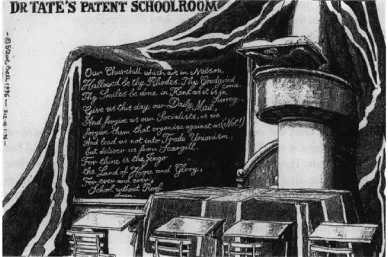

In January 1996 Dr Nicholas Tate, Chief Executive of the School Curriculum and Assessment Authority, argued the need for schools to teach a particular ‘canonical’ account of English national history, giving a clear priority to the action of monarchs, prime ministers and military heroes in shaping the nation’s destiny (this, by the way, was to be taught with an emphasis on strong narrative, simple use of biography, and confidence that history consisted of the communication of facts). The effect of the proposal to define Englishness like this was sardonically exposed by a cartoon published in the Guardian on 16 January. In a gloomy schoolroom a blackboard carried this parody of the Lord’s Prayer:

Our Churchill which art in Nelson

Hallowed be thy Rhodes. Thy Gradgrind come.

Thy Smiles be done in Kent as it is in Surrey.

Give us this day our Daily Mail,

And forgive us our Socialists, as we

forgive them that organise against us (Not!)

And lead us not into Trade Unionism,

but deliver us from Scargill.

For thine is the Jingo

the Land of Hope and Glory,

For ever and ever,

School without Roof

Amen.

Figure 1.1 Steve Bell cartoon, ‘Dr Tate’s Patent Schoolroom’

Source: Guardian, 16 January 1996.

Source: Guardian, 16 January 1996.

Tate’s interpretation of English national identity and this mocking counter-interpretation show clearly how nation is imbricated with loaded definitions of class, region, gender, ethnicity and culture (see, for example, Parker et al. 1992)—this is nation at the same level at which the car driver knows about driving. But I want to explore the conjecture that national identity also works at deeper strata than simply the content of the various overtly national practices, narratives, discourses, symbols and tropes through which national identity is conventionally presented and where it always appears one-sided and in dispute. I am interested in nation as an identity that can speak us even when we may think we are speaking for ourselves.

Consider the following case. Two people from the same country meet abroad and talk for half an hour. They might be of the same class, gender, religious affiliation, ethnic background or they might be alike in none of these. Now there would be a number of ways of analysing their exchange. One would be to consider its particular content; another, the various class, gender and other identities which come into play for the conversants; or the aspects in which the conversation reflects international identities (as European, say, or Islamic).

From these various co-existent possibilities I shall concentrate on how the text of their exchange might follow the procedures of a national discourse, procedures which include:

- the assignment of priorities, both thematic and discursive;

- strategies for managing agreement and disagreement;

- the notion of truth presumed;

- how the serious and less serious are defined against each other;

- control of tone, transition between topics;

- tropes and figures used;

- jokes (these might be especially significant).

If after their chat the couple felt that they had shared in a common national identity, it would not be so much because of what they said but because of how they said it. My methodological principle here is close to that of the linguist, Ferdinand de Saussure, when he set out to examine language not in the infinity of particular utterances (parole) but as an underlying system (langue). How far can we understand nation as a particular discursive formation?

Three difficulties in analysing nation

Current debate places a number of obstacles in the path of an approach to nation; especially (and significantly) in an English context these are all founded in a belief that nation is somehow not material, not real.

Nation as class dominance

In the first place there is a widely held belief that nation is a form of ideology, that is, a way of thinking designed to promote the interests of a particular social group. According to this view, the idea of nation, the national state and national unity is a hegemonic deception perpetrated by the ruling class in order to mask its own power (‘The working people have no country’, as the Communist Manifesto famously proclaims, Marx and Engels 1950, 1, p. 44, and see also Davis 1978 and Nimni 1994). So national identity is not real because it’s really just an exercise in class domination. As Raymond Williams asserts, with typical bluntness, ‘The building of states, at whatever level, is intrinsically a ruling-class operation’ (1983, p. 181).

It was Tom Nairn, who, drawing on Fanon’s discussion of ‘National Culture’, in a path-breaking work of 1977, The Break-Up of Britain, opposed this one-sided and reductive view of nation. Contrasting ‘negative’ and ‘positive’ nationalism—on the one hand, Nazism soaked in the worst excesses of barbarism, on the other, the Vietnamese struggle for independence—Nairn argued that national identity was not just imposedfrom above but spontaneously supported from below, not just an ideology but something actually lived into, for example, in the fight for national liberation.

Since all nations must have a moment of origin, there is a respect in which nation derives from an exercise of force rather than democratic enactment. This emerged clearly when the new South Africa was founded, in fraught circumstances. On 2 May 1994 when Nelson Mandela first spoke as elected President of the new democracy, addressing himself to ‘My fellow South Africans,’ he affirmed, ‘We might have our differences, but we are one people with a common destiny in our rich variety of culture, race and tradition’ (see Guardian, 3 May 1994). In an essay on Nelson Mandela published seven years earlier Jacques Derrida had looked forward to this very moment.

Asserting that all human institutions originate in an act of violence Derrida suggests that probably ‘such a coup de force always marks the foundation of a nation, state or nation-state’ (1987, p. 18) but in a way which anticipates legitimacy, democracy and ‘the general will’ (p. 19). A particular rhetorical form suits this anticipatory mode. Mandela’s assertion that ‘we are a people with a common destiny’, though it looks like a statement, is in fact a performative act, Derrida argues, ‘recording what will have been there, the unity of a nation, the founding of a state, while one is in the act of producing that event’ (p. 18). And the ‘originating violence’ attending the foundation of the nation-state ‘is forgotten only under certain conditions’ (p. 18).

In this account the violence inhering in state power never goes away but becomes forgotten—overlooked—in so far as the unity of a nation becomes a matter of the general will, as the state becomes supported by the people. Equation of constitutional legality with the general will is never complete though it will always remain a promise as to what will have been.

The birth of the new South Africa and Mandela’s speech provide another insight into how nation can produce a largely involuntary consensus. On 22 May 1994 this letter from M.E.Jones appeared in the Natal Sunday Tribune (I am grateful to Michael Green of the University of Natal for showing it to me):

I would like to extend my heartfelt thanks to President Nelson Mandela for a gift I didn’t even know I wanted, until May 10, 1994.

As part of probably one of the smallest minorities in this vast country (I am a white, suburban, thirty-something mother) I have never understood, let alone had any feelings of, nationalismand patriotism. I have never known what it is to identify with and feel part of a larger whole.

For the first time in my life I am moved when I hear our anthem being played, or see that multicoloured horizontal Y fluttering in the breeze. I have been moved to tears more often this week than in my entire life; and those tears have been of profound joy at finally having a country to claim as my own.

I would like to give a big thank you, from the bottom of my previously cynical and unpatriotic heart, to Mr Mandela, the African National Congress and all those wonderful South Africans who made it happen, for giving me a country to love.

The depth and intensity of my national pride and love has taken me completely by surprise, but what a warm, wonderful, heart-stirring feeling it is.

How far this is an untypical or extravagant reaction time will tell but the new country will not break up while there is a widespread identification with it as strong as that expressed in this letter. To try to understand the nation-state exclusively in terms of class power exercised through the state is simplistic and reductive.

Nation as ‘imagined community’

Marxist theories of nation are deficient not only in believing nation is imposed from the top but because in believing this they have assumed nationalism is an ideology and therefore, in some sense, just not real. Besides Tom Nairn, Benedict Anderson has done much to combat the view that nationalism should be classified ‘as an ideology’ when it is in fact a much wider, lived experience in a relation between social structures and subjectivity, more like kinship or religion or gender than something that should be treated as if it belonged ‘with “liberalism” or “fascism”’ (1991, p. 5).

However, Anderson is not able to come up with the account of nation as collective identity which his rejection of nation as ideology had shown to be necessary. In the absence of this he is driven to promulgate merely another version of nation as unreal when he claims they are ‘imagined communities’ (a view which has become something of an orthodoxy for theories of nation). Anderson is of course right to stress that nation, like the rest of human culture, is ‘imagined’ in the sense that it is constructed rather than the result of a natural process but this notion of ‘imagined communities’ is unsatisfactory, for two reasons.

Anderson cannot extricate himself from the conventional contrast of ‘traditional’ and ‘modern’ societies as an opposition between the real and the fake. The nation, he writes, is ‘an imagined political community’, ‘imagined (italics original) because the members of even the smallest nation will never know most of their fellow-members, meet them, or even hear of them, yet in the minds of each lives the image of their communion’ (p. 6). Here ‘the imaginary’ is defined in a way which appears familiar and unremarkable to an English reader because it is empiricist—thus imaginary supposed in opposition to personal knowledge, direct encounter and being within actual earshot of another person (the kind of thing, in other words, that is sometimes thought to be so attractive about small and ancient ‘organic’ groupings).

But now the argument cuts back in a different direction, for Anderson goes on to assert that ‘all communities larger than primordial villages of face-to-face contact (and perhaps even these) are imagined’ (p. 6). The parenthesis ‘(and perhaps even these)’ is obscure, and the generalisation itself evades the problem of what it is about human collectivities that might properly be described in terms of an opposition between real and imaginary. In the next sentence Anderson simply sidesteps the issue with an explicit statement that, ‘Communities are to be distinguished, not by their falsity/genuineness, but by the style in which they are imagined’ (p. 6). This conceptual muddle would not matter so much if his account subsequently went on to make clear what is meant by ‘style’ (if he means ‘discourse’, one might ask how he understands the concept). But his various explanations of nation as culture and ‘style’ (national language and print culture are important, nations take the place of a declining religion, and so on), suggestive as they are in a descriptive way, remain ad hoc, opportunistic and undertheorised.

This view of the pre-national community as real face-to-face contact contrasted with unreal national societies is embedded deep within British culture. It is starkly apparent when, for example, Raymond Williams comments that:

‘Nation’ as a term is radically connected with ‘native’. We are born into relationships which are typically settled in a place. This form of primary and ‘placeable’ bonding is of quite fundamental human and natural importance. Yet the jump from that to anything like the modern nation-state is entirely artificial.

(1983, p. 180)

And it is repeated by others—by Eric Hobsbawm when he refers to ‘the unavailability of real human communities’ and asks why having lostthese, people should ‘wish to imagine’ nations as their replacement (1992, p. 46), by a leading theorist of nation, Anthony D.Smith, who replying to Anderson’s arguments, goes along with the bland assumption that ‘all communities larger than villages are imagined’ (1993, p. 17).

This attitude to nation underwrites a nostalgic and sentimental desire to believe that face-to-face contact is real, free from interference by signs, language, ‘writing’, while opposed to this the larger, more impersonal groupings constructed by modernity are imaginary, false, unreal. In the pre-national culture, the lost organic community where everyone knows everyone else, people are supposedly directly present to each other without mediation while in the nation they are not.

That binary opposition cannot be sustained, as Jacques Derrida demonstrates with withering authority in his discussion of Rousseau and Lévi-Strauss. In a vigorous struggle to elude modernity, Rousseau puts forward the impossible idea of a community (in Derrida’s words) which is ‘immediately present to itself, without difference, a community of speech where all the members are within earshot’ (1976, p. 136). But, alas, it is the case for every speaking subject tha...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- FIGURES

- PREFACE

- PART I: NATION

- PART II: THE ENGLISH TRADITION

- PART III: ENGLISHNESS TODAY

- BIBLIOGRAPHY