Chapter 1

Historical perspectives in the study of dance

June Layson

1.1 INTRODUCTION

Chapter 1 provides the foundation line for the rest of this book in outlining and discussing the nature of history generally and, more particularly, dance history. It is acknowledged that at a basic level it is possible to study dance history, write about it and be involved in other forms of dance history communication without addressing such epistemological questions as what constitutes dance history, what purposes it serves, what roles are available to the dance historian and so on. However, it is contended here that any study of dance history, in whatever form and for whatever purpose, can be enlightened and enriched by an understanding of the nature of the dance history enterprise. To apprehend and appreciate the field of operation is a vital preliminary to acquiring knowledge and understanding in any area and dance history is no exception to this.

In section 1.2 the general historical perspective is outlined as the forerunner to a more detailed consideration in section 1.3 of dance in its historical perspective. Together these two sections reflect relatively well established perceptions of both general history and dance history. In section 1.4 the discussion is opened up to include reference to the current challenges being made to traditional approaches in the form of radical perceptual shifts and in the introduction of highly innovative practices. In the light of this discussion, section 1.5 identifies selected areas of dance history as an academic discipline requiring strategic reconsideration and redevelopment, and the chapter is summarized in section 1.6.

1.2 THE GENERAL HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE.

As an academic discipline history is often justified on the grounds of inherent worthwhileness since the past of any group of people is regarded as a cultural legacy to be valued. In addition, history is seen to provide links between the past and the present so that, through its study, the here and now can be informed.

These particular notions of history serve to emphasize its chronological core and its linearity. Nevertheless, this does not imply that such ideas can be conflated with a teleological stance which would promote the identification of ‘natural’ chronological progressions and beginnings and endings. Indeed, history may be diachronic in its study of particular thematic developments over time or synchronic in its study of a specific time-span devoid of reference to its historical antecedents, but it is, nevertheless, fundamentally concerned with the character of continuity and the nature of changes through time.

The historian’s role in this is traditionally seen as one of both chronicler and interpreter. Even so, in the quest to establish what happened in the past it is impossible to retrieve everything. Therefore, the historian is, inevitably, also a selector with the responsibility for distinguishing the important from the trivial, the central from the peripheral. Such selection, though, is always from the relative position of the researcher, whether declared or otherwise, and invariably reflects the demands of the project in hand, further external requirements and so on.

The working methods employed by the historian are based on sources, the residue or traces of the past, which more often than not are fragmentary and incomplete. These are critically appraised, assembled into logical relationships and structures and then used as the basis for historical communication, the commonest form of which is the written word, sometimes termed ‘historiography’. Historical writing is concerned both with recreating the past, and thus relies on description and connecting narrative, and interpreting the past, by means of analytical techniques.

From this necessarily brief outline of the domain of history and the role of the historian it is evident that it is far from being an exact science. Indeed the very idea of history being at all related to the sciences is vigorously challenged by the ‘new’ historians. Its grouping with the humanities and/or the social sciences acknowledges that characteristically it not only involves high degrees of technical skills but also requires abilities to synthesize, to make inferences, to interpret and to offer judgements and evaluations. This in turn means that history is essentially ‘open’, that is, always amenable to reinterpretation.

The essentially contested nature of history gives the discipline the potential for instability and creativity. The subject is periodically seen to be in a state of flux and there is an ongoing debate to determine its scope and rationale, to devise new methods and appropriate approaches and, more recently, to question the role of the historian. One of the implications of this openness is that to study history can involve engagement in an exciting and challenging area. Similarly, historical communication, in whatever form it takes, can engender imaginative and creative work with the real possibility of contributing to the knowledge base of the subject.

1.3 DANCE IN ITS HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES

In dance history all that has been touched upon in the preceding section applies, the crucial difference being that, instead of a general concern with the past, dance is now foregrounded. Dance history, as a body of knowledge, and the study of dance history, as a scholarly activity, constitute in some respects a hybrid discipline. This discipline shares many characteristics with history in general but, more importantly, forms one of the central methodologies of dance studies. The main contribution of dance history to the study of dance is that it reveals a highly complex human activity serving many purposes and developing a multiplicity of types which proliferate, prosper, decline and otherwise change through time.

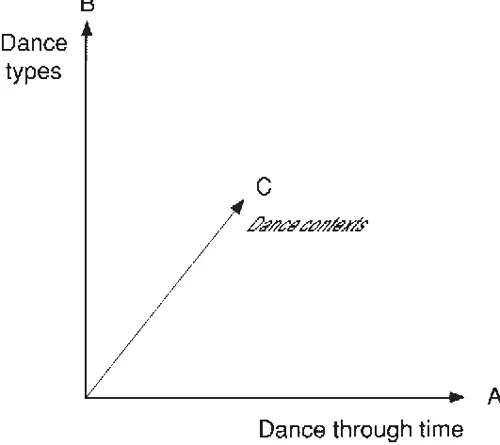

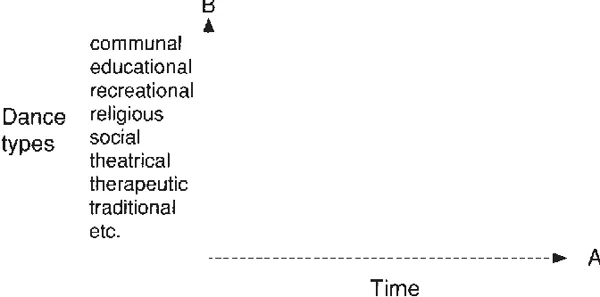

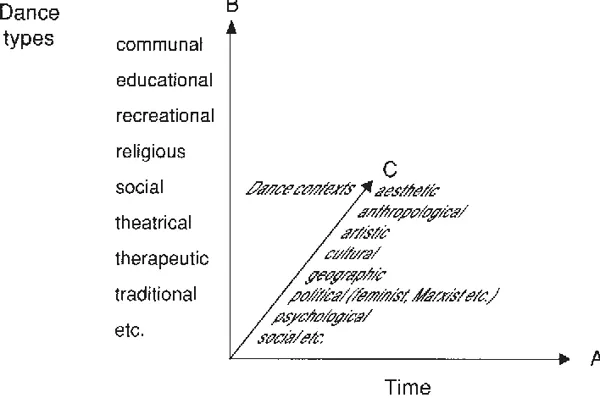

A convenient way of characterizing dance history as a body of knowledge and as a disciplined activity is by means of a simple three-dimensional model.1 Here it is used to explore different modes of engaging in dance history (Figure 1.1).

1.3.1 Dimension A—Dance through time

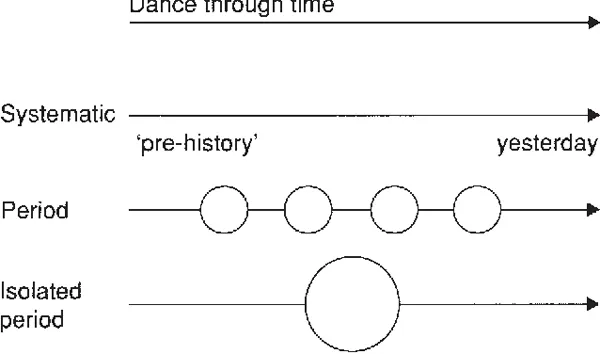

This is the fundamental dimension and defining characteristic for the area of study and it allows many different approaches (Figure 1.2).

The traditional approach is by means of a systematic study which attempts to cover all aspects of dance and either starts with ‘pre-history’ and concludes with the dance of yesterday or selects a sizeable portion of the whole, such as several centuries. This mode of study has the merit of moving steadily through time so that broad features, as in the growth and development of dance styles, can easily be historically situated.2 However, the disadvantages are considerable. Even if the dance of ‘pre-history’ can be studied, and, given the lack of evidence, this is clearly in doubt, or the dance of many centuries considered as a unified whole, which is also problematic, the attempt to encompass such a wide time-span inevitably leads to superficiality. Furthermore, in such study there is always the danger of succumbing to the notion that dance, like human activity in general, has evolved into ever more advanced states and is, in some way, ‘better’ as time progresses.

A period-based study may solve some of these problems because eras can be chosen which are highlights in the history of dance and offer opportunities for in-depth enquiry. Nevertheless, this may well be at the expense of identifying causes and effects, discerning longer term trends and understanding the reasons for the growth or decline in dance in preceding and subsequent eras.

By concentrating the study of dance on one isolated period it is possible to work in detail and to pay attention to single events and their relation to the time-span of the selected area. Here, though, the potential to note subtle shifts through several time periods in dance, and in attitudes towards it, is in jeopardy.

The ‘dance through time’ dimension serves a useful purpose because it ensures that events are placed in chronological order and it gives a temporal structure to dance history. However, the source base available for dance study is not uniform but increases rapidly as the twentieth century progresses and it is unsurprising that there are more materials extant for the twentieth than for any other century. This means that the opportunities for studying pre-twentiethcentury dance are hampered by the lack of a comprehensive dance source base. Such a factor reflects the ephemerality of dance and the comparatively recent establishment of dance studies as an academic discipline as much as the normal loss of material evidence through time. Even so the ‘silences’ concerning dance in the extant pre-and early-twentieth-century sources are telling.3

The use of a left-to-right arrow to denote the historical dimension of dance might give the impression that the logical and only way to study dance history is to proceed through time, from ‘then’ to ‘now’. In practice, though, there are several instances where this is not the case. Oral history and oral tradition are both important elements in studying specific types of dance,4 as are oral sources generally. In such cases the ‘here’ and ‘now’ is seen to provide access to ‘before’ and ‘then’ and, consequently, historical study is conducted ‘backwards’ through time.5

1.3.2 Dimension B—Dance types

This model (Figure 1.3) allows all types of dance to be identified and subsequently subdivided into their constituent parts (Figure 1.4).

The notion of dance types is at the macrocosmic level and derived from their function and context. For example, a distinction can be made between traditional dances, which usually have a ceremonial, celebratory function, are popular, that is, ‘of the people’, and tend to endure, and social dances which, too, are popular but are more concerned with reinforcing individual and group relationships, are a form of entertainment and are liable to rapid changes in fashion.

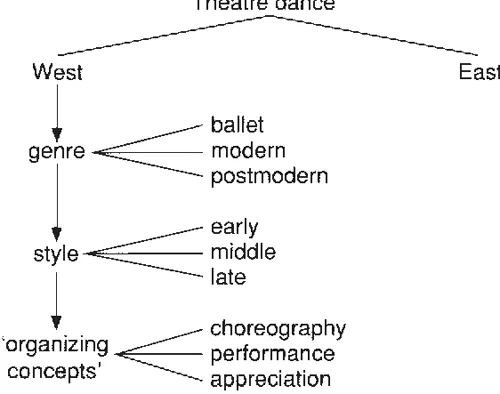

In moving towards the microcosmic level it is possible to subdivide a dance type in several ways. For example, theatre dance can initially be divided on one of several geographical bases and subsequently by genre, style and ‘organizing concepts’ (Adshead 1988) (Figure 1.5).

Simply by combining the time and type dimensions the immensity of the area encompassed by dance history is partially revealed as any one or more of the sub-sets, in various combinations, can be studied within appropriately selected periods of time.

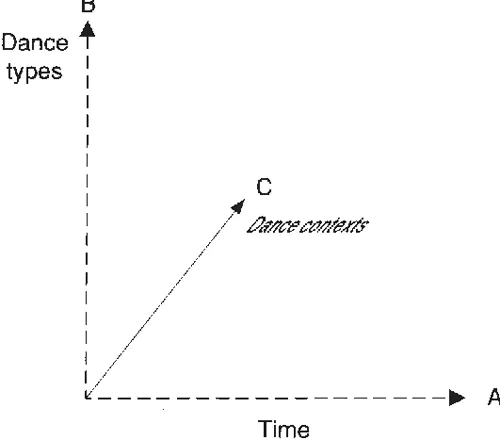

1.3.3 Dimension C—Dance contexts

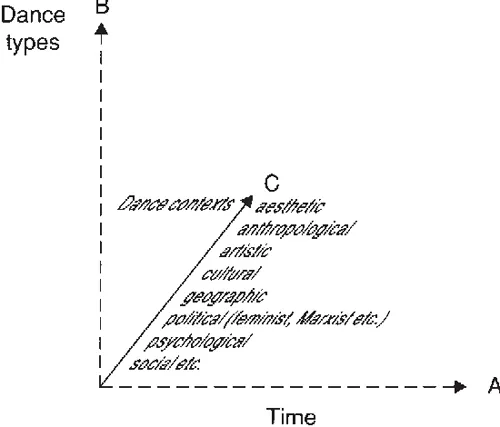

Dance is ultimately defined by its contexts (Figure 1.6). The consideration of, for example, place, location, artistic or social contexts has traditionally been the concern of dance historians, though often only in a perfunctory manner. However, the need to study dance within its appropriate circumstances and in relation to prevailing ideas and attitudes is vital if dance is to be understood both in its own terms and that of the many contexts in which it exists (Figure 1.7).

Because the contexts in which dance exists are manifold there is a potential tension between studying the dance itself in depth and studying it within its immediate and wider contexts. A detailed examination and analysis of dance devoid of its contiguous and contemporaneous contexts is likely to be seriously flawed since the dance is both part of and derived from its contexts. Similarly, a multidisciplinary contextual approach taken to extremes may, instead of informing the study of dance, merely reduce it to the status of exemplar. There may be occasions when either extreme approach is justified but generally the need is to find a balance between these polarities. Even so, such problems are likely to persist since, as the study of dance gains momentum, the development of, for example, highly detailed choreographic analyses and, coexistently, the recognition of the crucial nature of contextual concerns, will need to be reconciled.

With the third dimension articulated, the vastness and complexity of the area of dance history, hinted at earlier, is now clearly evident. While its subject boundaries can barely be glimpsed it is probably the case that only a very small percentage of dance history worldwide has been studied to date. This may appear daunting but it also presents exciting challenges to future dance historians.

A model of the subject area for dance history is shown in Figure 1.8.

1.4 THE TRADITIONAL AND THE NEW: CHANGING PERSPECTIVES IN DANCE HISTORY

Although it is impossible in this text to do justice to both traditional and ‘new history’ orthodoxies in relation to their rationale, perceived terms of reference and prevailing ideologies, it is profitable at this juncture to identify those concerns which currently have an impact upon dance history or have the potential to do so. In fact the debate concerning ‘new’ dance history is, as yet, in its infancy.

What might be termed the traditional approach to history originated in central Europe and ‘by the second half of the nineteenth century was beginning to establish itself throughout the Western world as an autonomous academic discipline’ (Marwick 1989:43). Nevertheless, during the early twentieth century and subsequently, the fundamental bases of the subject as an area of study were still a matter for debate. Notions such as the ‘proper’ focus of history (either the political state or a wider concern with economic, social and other factors), the objectivity of the historian (either an ideal to be attained or the explicit acknowledgement of subjective involvement) and the methodologies to be employed (ranging from support for the ‘scientific’ to embracing techniques from new disciplines such as psychology and statistics) were raised as various schools of thought held sway.6

The current challenges to traditional history stem fr...