![]()

part 1

Weimar to The Dramatic Workshop

Piscator is the greatest theatre man of our time, and possibly the greatest theatre man of all time. His love of experiment, his great scenic innovations, existed to serve humankind through all the means of the theatre.

Bertolt Brecht

1945 was a time of enormous political and cultural confusion. The post-war elation had died domestically and the upsurge of the 60’s had not yet begun …

The little theatre movement of the Provincetown Playhouse was over and The Barter Theatre had lost some of its potency, though it still continues to inspire us. The Group Theatre, which had given us so much hope, degenerated into the more conventional Theatre Guild and, except for an all-too-rare new play by Eugene O’Neill, nothing was happening on the theatre scene.

Yet Erwin Piscator, though he carried the burden of much disappointment from his inability to find a place in the Broadway milieu – the rejection of Gilbert Miller who had promised him a Broadway production of his War and Peace, as well as his desire not to teach, but to produce plays – none of this discouraged his underlying belief in a theatre of meaning and political vigor. He fought for it, and he transmitted that vigor to his students.

He was not easy on the actor; his demands were high and for some unreachable. He wanted absolute attention, absolute concentration, but above all he asked the performer to change her focus. He called this Objective Acting, in which the object of the actor’s focus is the spectator.

The actor speaks, stands in the lights, is the object of the audience’s attention …

But the actor’s work is to communicate with the audience. Traditionally, this would occur through her relationships to the other actors on stage – but in Piscator’s and Brecht’s Epic Theatre the fictional relationship between the character the actors are portraying is less real than the actual relationships between actor and audience members.

This required a special kind of playwright, and Brecht’s Epic Theatre offers such a means.

But Piscator also produced the Classics. The examples of his Schiller play, The Robbers, and Sartre’s The Flies, and a version of Eumenidies, are outstanding. Accompanied by an examination of the techniques he developed in such productions, he guided us to understanding the ways we could accomplish this essential shift, this initial shift of objective.

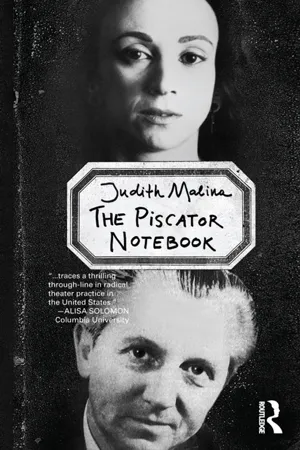

I started to keep a Notebook on February 5, 1945, when I began my studies at Erwin Piscator’s Dramatic Workshop at The New School for Social Research in New York. I was aware of, and even in awe of Piscator’s reputation when I first came to the Workshop – and in a certain sense one could say that the encounter was predestined.

Personal History

My mother, Rosel Zamojre, was an idealistic young actress in the city of Kiel, a naval and submarine base in northern Germany. She was an admirer of Erwin Piscator, the revolutionary young director who was the bright hope of the avant-garde theatre of the Weimar Republic. Her ambition was to work with him when she finished school. She took part in Kieler theatricals, while she worked in the shop where my grandparents sold linens and lace. Her observant Jewish family must surely have disapproved of her theatrical aspirations.

But then she met Max Malina, an equally idealistic young rabbi, at that time serving unhappily as a chaplain in the German army. She fell in love … and he soon found a way to get out of the army.

It was in those days unthinkable that a woman could be both a rabbi’s wife and an actress, so these two young people agreed that Rosel would give up her dream of the theatre, but that they would have a daughter who would become an actress; a surrogate, as it were, for Rosel’s abandoned career.

I was born in Kiel, in June 1926, intended for a theatrical life – hopefully even in Piscator’s theatre. Piscator was 33 years old when I was born, and was the director of the Volksbühne in Berlin. He had just opened Schiller’s Die Räuber, and was rehearsing Ernst Toller’s Hoppla, wir leben!

And it came to pass that Germany fell upon evil days, and my father, foreseeing the disaster approaching for the Jewish people, emigrated with my mother and me, in 1929, to New York City. There he founded The German Jewish Congregation, and devoted himself to making America’s Jewish community aware of the growing threat in Germany.

Erwin Piscator: Germany to New York City

When Piscator left Germany in 1936, it was high time for a Communist revolutionary to leave. Though he was not Jewish, Thea Kirfel-Lenk, in her valuable book Erwin Piscator im Exil in den USA (Kirfel-Lenk 1984: 145) reproduces a document from the SS files of 1939 in which Piscator is designated as a Jew, despite it being well known that he was a descendant of Johannes Piscator, a Protestant theologian who translated the bible into German in 1600.

Piscator’s history is one of heroic perseverance. He had been an apprentice actor in Munich’s Hoftheater, but experienced a crise de conscience on the battlefield in Ypres, Belgium during the First World War. He was digging a trench, shells bursting all around him, surrounded by the wounded and the dead. A sergeant came by and noted the soldier’s clumsiness with the shovel and asked him mockingly what he did for a living in civilian life. Young Erwin felt humiliated when he answered sheepishly, “I’m … an actor,” and wondered why it made him ashamed.

He was determined thereafter to make the work of theatre meaningful work, to renounce the kind of theatre that made him feel disgraced to say the word “actor,” to redeem the art from its degraded state. After the war he made the theatre his field of battle. In February 1942, Piscator remembered it this way in his essay on “The Theatre of the Future” in Tomorrow Magazine:

War was hateful to me, so hateful that after the bitter debacle of 1918, I enlisted in the political struggle for permanent peace.

In 1919 Piscator participated in the formation of a small avant-garde theatre in Königsberg, called The Tribunal, which produced plays by Wedekind and Kaiser, and Strindberg’s Spook Sonata in which Piscator played the young hero, Arkenholtz. Perhaps most significantly, it also produced The Transfiguration (Die Wandlung), a play of revolutionary pacifism that Ernst Toller had written in prison, after his experiences with the Soviet Republic of Bavaria, in whose brief but luminous story Toller was an active participant.

Germany was a political hotbed in 1919. The disaster of the First World War had set the stage for the uprising of the Spartacus League, the subsequent murders of Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, as well as the founding of the Soviet Republic of Bavaria by artists and intellectuals, soon followed by its bloody suppression. All this made for an atmosphere of revolutionary unrest that heightened the fervor of the times.

Leopold Jessner, who Piscator sometimes referred to as his teacher, was appointed head of the Prussian State Theatre. Dada flourished. Piscator organized several Dada events, as the Dadaists attempted “to put their nihilism to political use.” In The Theatre of Erwin Piscator by John Willett, Willett quotes Piscator: “Dada saw where art without roots was leading, but Dada is not the answer.” (Willett 1979: 47)

At The Dramatic Workshop, Piscator told the story of one of these Dada events, but I imagine that the details are apocryphal, because they sound almost too good to be true. Shown at a classy theatre with a well-dressed audience, the curtain opened on an empty stage, with large barrels piled high upstage. Then nothing happened. No actors, no music, nothing. After a time the audience grew restive, and began protesting, and shouting and berating the company as frauds, whereupon actors dressed as firemen barged onto the stage, and hosed down the audience with water. The insulted theatre-goers, seeing their wives’ fine dresses drenched, rose up in anger and attacked the firemen, whereupon the barrels opened and 25 professional wrestlers emerged, and forced the audience back into their seats. Piscator told this story with gusto; perhaps it was one of those fantasies that artists like to conjure, even if they can’t fulfill them, or perhaps something like this really happened. But hearing about it, in 1946, I know that visions of Paradise danced in my head.

In October of 1920 Piscator founded The Proletarian Theatre in Berlin, performing in various halls plays by Kaiser and Gorky and one by Upton Sinclair, in which Piscator appeared among the anonymous performers. Though modest in size and technical capacity, The Proletarian Theatre included such notables as John Heartfield, who projected maps and photomontage onto the scenery, and Lazlo Moboly-Nagy, who worked with symbolic constructions. The Proletarian Theatre produced five plays, including the brutally titled How Much Longer, You Whore of Bourgeois Justice? Six months later the license of The Proletarian Theatre was revoked and it was closed, leaving behind plans for plays by Ivan Goll, as well as a production of Toller’s Masse-Mensch, which the Volksbühne presented instead, without Piscator.

In 1924 Piscator created the Revue Roter Rummel, called RRR, for the Communist Party (KPD) election campaign of 1924–25. There were 14 scenes which were, according to Willett, “a model for the agit-prop movement.” Scenes of decadent Berlin night life were interrupted by actors playing workers who came up onto the stage from the audience and proclaimed the Victory of the Proletariat, ending with a rousing chorus of The Internationale. The KPD lost the election by 1,000,000 votes.

Piscator, however, had discovered the flexibility of the revue form, whose short scenes could be altered or added to, night by night. In 1925 the KPD asked him for a pageant to open the party conference, for which he created Trotz Alldem! (In Spite of Everything!), with 24 scenes, numerous historical film sequences, and 200 performers. Only two performances were given, both to packed houses. Piscator wanted more performances but the party said no.

The spirit of experiment was alive everywhere. In Moscow, in 1922, Vsevolod Meyerhold produced the seminal constructivist play Commelynck, which launched his theory of biomechanics. In 1923, Meyerhold formed the agit-prop troupe the Blue Blouses, which traversed Russia in a riotously painted train, and taught biomechanical performance techniques to peasants and factory workers.

From 1924 to 1927 Piscator directed the Volksbühne in Berlin, opening with Fahnen (Flags), about the Chicago anarchists of 1886–87, and which its author, Alfred Paquet, subtitled “an Epic Drama.” Piscator used a complicated divided set on a revolving stage with a treadmill street running through it, and images of the characters and documentary material projected on either side of the stage. A narrator spoke the prologue, and a balladeer commented in song. In this way Piscator intended “to connect the stage and the auditorium.” He felt that he had succeeded in this. Piscator later wrote that

The wall dividing stage from audience was swept away; the whole building a meeting hall. The audience drawn onto the stage.

It is strange that he said it so clearly, and described it so precisely, and yet he did not do it. He was speaking metaphorically when he said, “the wall dividing … was swept away.” He continued to regard the division of the audience’s and the actors’ areas as sacrosanct. “The audience was drawn onto the stage,” he wrote, but no audience members were actually encouraged to set foot on the stage. It was only a beginning.

Between 1924 and 1927 Piscator directed plays for the Volksbühne, each production experimenting with technical and cinematic forms and novel uses of screens and projectors, sometimes mixing or intercutting live actors and their screen images, sometimes playing two or three scenes simultaneously, but always reworking each play to emphasize its moral and political meaning. With Gewitter über Gottland (Storm over Gottland), which deals with the struggle between Hanseatic capitalists and a communistic league of revolutionaries, the management of the Volksbühne rejected him, saying, “This type of production is incompatible with the Volksbühne’s principle of political neutrality.” A great public controversy ensued, with hundreds of actors and thousands of Communists trying in vain to vindicate Piscator’s position.

But Piscator was already preparing his own theatre, the Piscatorbühne, which he opened in 1927 on Nollendorfplatz in Berlin with Toller’s Hoppla, wir leben! With Hoppla, he began to overturn all the conventions of staging. Its success lay in its fusing of staging innovations and political relevance. Traugott Müller’s set was a four-story scaffolding built on a revolving stage. The play considers a cross-section of society, and this was literally rendered by the set. The different acting areas diagrammed the social order, the actors representing social classes.

He followed this success, which ran for two months, with another overwhelmingly technical production, Rasputin, the Romanovs, the War and the People that Rose Up Against Them, adapted from Tolstoy by the Dramaturgical Collective of the Piscatorbühne, who added the characters of Lenin, Trotsky and the e...