1

VARIATION, CHANGE AND STANDARDS

This book treats a subject which, outside France, has lost much of its appeal: the history of the French language. The great discoveries made over the past century and a half by scholars exploring the historical links between French, Latin and the other Romance languages have now been largely assimilated, and the questions they raised pushed from the forefront of research by linguists with new preoccupations. The medieval language, which thirty years ago exerted a powerful fascination upon perhaps a majority of French-language specialists, nowadays sets off frissons of curiosity among only a diminishing band of researchers. Moreover, so many books bearing the title ‘History of the French Language’ have been published over the years that a bibliographer could be forgiven for classifying them as a separate genre. So, in view of all this, we are bound to ask why anyone should wish to start again on such a well-worn topic, in the last decade of the twentieth century. What more is there to say?

The very obvious answer to this question is that a subject as broad as this can never be exhausted. Even after all the work so far done in the history of French, a host of interesting problems remain unsolved, a great array of questions remain unanswered. On the one side, new linguistic data from the past are constantly coming to light (in the form very often of texts retrieved from archive shelves hitherto inaccessible to scholars)– and it is possible that there is a richer source of such data in France than in most European countries, given the size of France and its wealth and populousness in past centuries. On the other side, new hypotheses, new interpretations of the available data, are constantly being called for to enable us to square our ideas about language in the past with current theories about the nature of language in general.

The present volume will then venture into the somewhat unfashionable field of ‘the history of the French language’, for its author is confident that there are new things to be said and new patterns to be discovered. However, the scope of this book will be a good deal narrower than that covered by traditional histories: we will be concerned more with interpreting certain aspects of the history of French in a new way than with presenting data previously unknown to the world of scholarship. Furthermore, a distinction is usually drawn between the internal, linguistic history of French (the development of its soundsystem, its morphology, etc.) and the external, sociolinguistic history of the language (the developing relationship between French and the population which uses it) – though the uncovering of a close relationship between language variation and language change has meant that the distinction between the linguistic and the sociolinguistic in the history of a language is now seen to be a good deal less clear-cut than it was previously. Whereas writers of ‘histories of the language’ have usually treated both of these aspects, in varying degrees of thoroughness, in this book we will be concerned more with the latter than with the former, more with the sociolinguistic than the linguistic, for the explosion of sociolinguistic research over the past thirty years has produced results which are proving very enlightening for the linguistic historian. Working on the basis of data drawn from languages currently in use, sociolinguists have developed insights and analytical frames which can be projected back in time to help us elucidate the changing patterns of language use in the remoter past. The area of sociolinguistic research, which is to provide the central theme of this book, is macrolinguistic rather than microlinguistic in scope, namely the topic of language standardisation.

The emergence of the great European standard languages has left a profound imprint on European culture, most obviously in the way Europeans subconsciously view language and its role in society: it has come to be widely accepted, for instance, that the ideal state of a language is one of homogeneity and uniformity (rather than diversity), that its ideal form is to be found in writing (rather than in speech), and that the ideal distribution of languages is for there to be a separate language for every separate ‘nation’ (see Deutsch 1968). This nexus of ideas was not present in premodern Europe, nor is it axiomatic in many non-European societies today. These ideas are bound up with the development of standard languages and the spread of literacy, and are the product of a particular series of sociocultural developments which occurred at a particular stage in European history. In no European society did they take deeper root than in France, and their mark is to be seen in many aspects of French culture, witnessed for instance in the profound respect felt for literary authors seen as creators of la belle langue and in the cultivation of the French language as a central part of the ‘national patrimony’. They have also greatly influenced the way the history of the French language has hitherto been written. In this introductory chapter we will examine how subjective attitudes to language in France may have influenced the writing of French linguistic history, and then we will attempt to set out a different approach to the history of French.

SUBJECTIVE ATTITUDES AND HISTORIES OF FRENCH

When we examine subjective attitudes to language current in France at the present time, one of the most striking features we come across is the depth of reverence felt in many parts of society towards the standard language: linguistic prescriptivism (a readiness to condemn non-standard uses of the language) and linguistic purism (a desire to protect the traditional standard from ‘contaminations’ from any source, be they foreign loanwords or internally generated variation and change), have developed roots in French culture which go particularly deep. The belief that the ideal state of the language is one of uniformity and that linguistic heterogeneity is detrimental to effective communication is firmly entrenched, and as an expression of this belief the French language has acquired a rigidly codified standard form which exerts powerful pressures upon its users. While no one could claim that speakers of French in France hang upon every word which issues from the lips of a member of the Académie Française, it is nevertheless true that many of them have developed a strong sense of what is correct in French and what is not, and that, as a result, many French people are actually ashamed of the way they speak. Intolerance of variation and hostility to language change run particularly deep in certain quarters and, paradoxically, it is probably because of this that the difference between the ‘correct’ and colloquial forms of French is now very considerable: oppressive norms are always an incitement to rebellion.

Moreover, it is widely believed that the French language exists in its purest form in writing and that speaking usually involves a falling away from the ideal. There seems to be general agreement, among non-linguists at any rate, that the standard (written) language as a linguistic system is inherently ‘better’ (clearer, more logical) than all other varieties current in the community – colloquial forms, regional forms, lower-class forms, patois, etc. The myth of the ‘clarity’ and ‘logic’ inherent in the standard French language is extremely pervasive. In many societies in the modern world, language usage is not at all so standardised and pressure to conform to social norms in speech is a good deal weaker. In view of the importance of attitudes to language in the rest of this book, let us look in more detail at the way the French layperson typically regards the different language varieties present in French.

The average layperson in France (like speakers of all languages) is acutely aware of the variation which exists within French. He or she is sensitive to the most subtle distinctions among the particular ‘accents’ and styles he or she encounters. However, when it comes to describing these different language varieties the terminology (or metalanguage) at his/her disposal is usually heavily laden with value-judgements derived from a long and powerful tradition of prescriptivism. This can be clearly seen when we look at the traditional terms used to discuss language variation in French. To a layperson in France the answer to the question ‘What is the French language?’ is straightforward: he/she identifies la langue française with the standard, normally the written, form of it. Although he/she will probably regard the informal speech of the educated middle classes (traditionally labelled le français familier) as coming within the general scope of ‘the French language’ – for standard languages are usually thought to have formal and informal variants– other varieties he/she will exclude. It is quite usual for French-speaking laypersons to regard slang or regional forms as not being French at all: ‘Ce n’est pas du français ça, c’est de l’argot.’

The most pervasive of the ‘non-standard’ varieties identified by the layperson is possibly working-class speech, commonly labelled le français populaire. Its vocabulary is closely associated with argot, a large set of stigmatised lexical items thought to have originated in the Paris underworld. Beyond le français familier and le français populaire come the dialectes and patois, used by the rustic populace in the various provinces of France (Norman, Picard, Burgundian, etc.), and widely considered by the layperson to be ‘debased, corrupt forms of French’. Dialectes usually have greater dignity than patois, for they (allegedly) possess a written form and a higher level of standardisation. For many a French layperson, in fact, the patois are the lowest form of language life, associated as they are with the despised culture of the peasantry, and subject as they are to infinite variability. Intermediary between the patois and the langue française come regional accents; these involve deviations in pronunciation from the Parisian norm and are commonly associated with the various français régionaux (regional varieties of French). The latter are obviously distinguished from the langues régionales (Basque, Breton, Flemish, Alsatian, Corsican, Catalan and Occitan) which are felt (rightly in some cases) to be genetically different from French and which enjoy various levels of prestige/ stigmatisation.

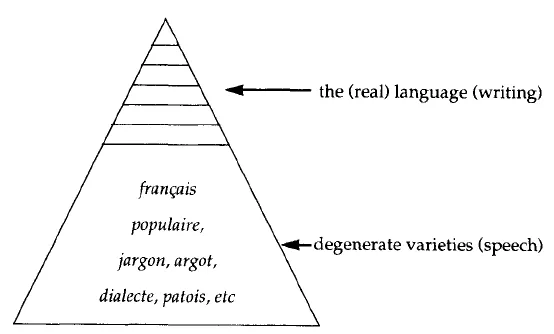

As we can see, the layperson’s metalanguage in this area contains a large judgemental element. The layperson tends not to view the different language varieties current in society in a detached way, instead attributing to each of them a social meaning based on culturally transmitted stereotypes. In most of our superficial day-to-day dealings with people, we judge them with reference to these stereotypes. Social attitudes to non-standard speech in France as in Britain are not always unfavourable. Nonstandard varieties can be viewed with affection, inducing a sense of security and homeliness. For instance, positive feelings towards one’s own local speech tend to be bound up with a sense of belonging to a small community within society at large. Informal style is normally taken to be more friendly than formal style. Rural varieties are often more favourably regarded than urban ones (see Ryan and Giles 1982: esp. 22–7). However, in France, as in Britain, such non-standard varieties are rarely given high status when judged by wider social norms of acceptability. In these countries institutional pressure to conform to standard linguistic usage has been strong for so long that people have come to believe that the standard language is the only authentic form of the language and that all non-standard varieties are merely failed attempts to express oneself properly. The layperson’s model seems then to be something like that shown in Figure 1.

It is likely that the social norms presented by the French standard language derive much of their strength from the highly centralised nature of French society, strongly focused as it is on Paris. They are greatly reinforced, however, by the central role which language has played over the past two centuries in the definition of French national identity – the standardised variety of French is more than an efficient vehicle for communication across the vast length and breadth of France; it serves as a powerful symbol fostering among French people a sense of national solidarity (internal cohesion) and a feeling of their uniqueness in comparison with other nations (external distinction). In pursuance of the principle, first enunciated at the time of the French Revolution, that ‘la langue doit être une comme la République’ (‘there should be a single language, just as there is a single Republic’), non-standard languages and dialects were until quite recently persecuted with great ruthlessness. The overwhelming dominance of the standard language which has resulted in France (see Grillo 1989) contrasts quite starkly with the situation holding in many other societies where the ideal of ‘one nation – one language’ is much further from being realised– that is to say that two or more languages are widely used within society, distributed either functionally (e.g. English and Hindi in India), geographically (e.g. English and French in Canada) or socially (e.g. Anglo-Norman and Middle English in medieval England). On the external scene, given that for many French people their language has come to stand for French national identity, French culture and France’s position in the world, strenuous official efforts have been and are still being deployed to maintain the use of French as an international language, and to combat the effects of outside (usually lexical) influences on the language, as if they were a hostile invasion. In many other societies, including those of the Anglophone world, the symbolic potency of the national language is weaker: since it is less of a symbol of national identity, speakers have a somewhat more relaxed attitude to its role in the world and to foreign linguistic influence upon it.

Figure 1 A layperson’s view of varieties of French

Reverential attitudes towards the standard language, such as those we have just outlined, are to be found to some degree in most European societies, sharing as they do similar attitudes to literacy and to nationhood. However, it is clear that these beliefs are particularly pervasive in France, and that they are not only apparent in the language attitudes of laypersons but are also to be found lurking in an insidious way in work published about the French language by respected scholars, notably in histories of the language.

It is not unfair to maintain that the way in which the history of the French language has traditionally been written (principally in France, but elsewhere too) has in fact been heavily conditioned by reverential attitudes to the standard language and by linguistic prescriptivism. Let us attempt to substantiate this by looking at certain basic features shared by many traditional histories of French: (1) the unidimensional nature of many of these histories; and (2) their tendency to a belief in the fundamental uniqueness of France and the French language.

When we probe traditional histories of French on the very basic question of what they mean by ‘the French language’, explicit definitions are hard to find, but the implicit scope of the term is commonly restricted to ‘the standard language’ (normally extended backwards in time to include what the historian regards as its legitimate antecedents, e.g. ‘Francian’, the medieval dialect of the Paris region). Many of these studies are in essence histories of the standard variety only (principally in its literary manifestations), implying that other varieties of French (e.g. colloquial, popular and regional forms) are of little interest. Of course, the freedom of linguistic historians to explore spoken forms of the language in past centuries is severely limited by the nature of the surviving data, but this does not justify the assumption all too commonly made that the variety of French found in written (and especially literary) texts constitutes ‘the quintessential form of the language’, and that the linguistic usage of the upper social groups is the only one possessing real historical significance. There is as yet no comprehensive ‘history of colloquial French’ to compare, for instance with Wyld’s A History of Modern Colloquial English (Wyld 1920, but see Stimm 1980).

This concentration on the evolution of a single variety of French often cloaks a teleological yearning on the part of the historian for linguistic homogeneity. This is to say that many traditional histories seem to have had as their underlying purpose to trace the gradual reduction of obstacles to linguistic uniformity and to point the way to the seemingly inevitable triumph of the standard language. In some cases one even feels that this purpose was actually to legitimise the triumph of the standard (see Bergounioux 1989). Such an approach has a long pedigree: an (unstated) function of early histories of French (they began to be written in the sixteenth century) was quite evidently to confer historical legitimacy upon the newly forming standard language, in its rather unequal relationship with the non-standard varieties current in the community, and in its competition for status with other more dignified languages like Latin, Greek and Italian. A remarkable early example is to be found in Claude Fauchet’s Recueil de l’origine de la langue et poésie françoise, ryme et romans (1581). It should be said, in fairness, that this approach to language history is by no means monopolised by historians of French: standard languages commonly acquire what can be termed ‘retrospective historicity’, that is they are given, after the event, a glorious past which helps set them apart from less prestigious varieties current in the community (see Haugen 1972).

A multidimensional history would not be so narrowly focused. It would assume that no speech community is ever linguistically homogeneous, and so would attempt to trace, within the severe limits imposed by the evidence available, the development of the whole amalgam of varieties which make up ‘the language’. This raises of course the general problem of ‘idealisation’ in linguistic description – the degree to which linguists ignore aspects of the variability of their data. If general statements are to be made about linguistic evolution, then some degree of idealisation is inevitable. However, traditional histories have tended to evacuate too many variable elements from the data they have wanted to consider, insufficiently aware perhaps that language change has its very roots in language variation (see below, p.).

Great impetus to the writing of histories of French was provided in the first half of the nineteenth century by the development of comparative philology and the general diffusion of the ideas of Romantic nationalism. Influenced no doubt by W. von Humboldt’s (1836) view of language as an expression of the spirit of a people, a great deal of effort began to be devoted at that time to exploring and defining France’s cult...