![]()

1

Time, Space and Narrative

Reflections on Architecture, Literature and Modernity

Jonathan Charley

The city spread over a plain into distances further than the eye could see. Whichever way he turned there was no end to it, nothing but houses and apartment blocks, streets, squares, towers, old and new quarters of town, mildewy storm-battered rented barracks and skyscrapers faced with modern marble, main roads and alleys, factories, workshops, gasometers and the clumsy looking great hall that he recognised from her as the slaughterhouse. And chimneys, chimneys everywhere …

Karinthy 2008: 111

Intangibility and the Poets of Modernity

It is with an image of the limitless concrete geometries from the top of the Banespa Bank in Sao Paulo and the ziggurats and leaping flames from the opening clip of Blade Runner that I begin my course every year on the History of the Modern City. Like my vain attempt to draw Borges’ metaphor for the universe, the indefinite and infinite Library of Babel, it is a vision of a metropolis that has no centre and no end. And as it drifts and stumbles outwards to the periphery before disappearing into the hazy smog of the horizon, it is as if it is demonically possessed with a speed and complexity that mocks our efforts at comprehension, and defies our knowledge of earthbound demographics, semiotics and urban economics. As dusk falls over this city of twenty million souls, and millions upon millions of lights flicker and illuminate a nocturnal kaleidoscope of objects and bodies, the scene is almost indistinguishable from the Asimovian mega cities beloved of the fantastic imagination that have bled and bled until they enclose the entire surface of the globe. The first generation of modern writers were likewise shocked and astonished as they gazed in awe at the hypnotic antinomies and creatively destructive patterns of the nineteenth-century capitalist metropolis. It is why Walter Benjamin, Marshall Berman and many others have found such lyrical power in one of the greatest poets of modernity, Baudelaire, who on his urban drifts through Paris tells us that modernity is best understood as ‘the indefinable … the transient, the fleeting, and the contingent’1 (Baudelaire 2006: 399).

Figure 1.1 ‘The unknowable and impossible city’, Sao Paulo

Equally poetic in his depiction of modern life was Marx, who if legend is to be believed drafted the Communist Manifesto in the Swan Bar in Brussels’ Grand Place. Surrounded by the ornate guild houses and exotic town halls that reinforce Belgium’s claim to be one of the first industrial nations, and having fled from one European capital city to another, he was understandably mesmerised by the forces unleashed by capitalist production. In a phrase that he could well have penned from the top of the Banespa, he tells us that: ‘In scarce one hundred years the bourgeoisie has created more massive and colossal productive forces than have all preceding generations together.’ But he also warns us. The bourgeois world is haunted. It is stalked by illusions, spectres and ghosts that have conspired not only to create, but to destroy a society that is characterised by nothing less than the ‘constant revolutionising of production, uninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions, everlasting uncertainty and agitation’ (Marx 1990: 223). It was a sight at which Lukacs simply threw his arms up in the air and from the pulpit announced: ‘And the nature of history is precisely that every definition degenerates into an illusion: history is the history of the unceasing overthrow of the objective forms that shape the life of man’ (Lukacs 1983: 186).

It is this ephemeral and dynamic world, in which space splinters, time accelerates and technological wizardry is layered over lo-fi urban misery, that the modern writer and architect attempt to make sense of.2 But it is no easy task. The modern city would soon shake with the unfamiliar noise of machinery and early automobiles, ring to the shrill tones of telephones, spin with the whirr of a movie camera, and erupt in abstract splashes of colour and shape. Not only this but capitalist modernity appeared to have created a peculiarly dialectical reality, in which the world had been split into multiplications of increasingly fuzzy but powerfully evocative binary metaphors: civilisation and barbarism, capitalist and worker, coloniser and colonised, black and white, man and woman, sane and mad.

Inevitably these transformations in the structure and patterns of everyday life were reflected in what Bakhtin referred to as the chronotopic (literally ‘space-time’) organisation of literary texts.3 In fact the novel undergoes a profound chronotopic shift that is exemplified by the difference between Tolstoy’s War and Peace (1869) and Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment (1866). Whereas the former, despite its metropolitan encounters, still feels with its idealised portraits of peasant life like a novel run on agricultural time, the latter, one of the first great urban thrillers, beats with the distinctly modern rhythm of boulevards, pavement footsteps and murderous anti-heroes.

Like a fading memory, the pre-capitalist world of villages, churches and fields, of priests, lords and peasants, living a life governed by seasons, tithes and calls to prayer, retreats into the literary hinterland. In its place comes the chronotopic vocabulary of modern capitalism and the battle cries of bourgeoisie and working class. Together they inhabit a new city made up of arcades, mills, factories, terraces, mines and railway stations in which time is governed according to quite new and strange rules. The day is now regimented by the click of the clocking-in card, the siren of the factory, piece rate wages and the speed of the production line. It all amounted to nothing less than a full-blown temporal revolution engineered towards the perpetual speed-up of everyday life, economic efficiency and the maximisation of profits. This then, is the space–time terrain in which the narratives of modern literature and indeed the plots of modern architecture unfold, meet and merge.

By the turn of the twentieth century this metropolitan experience had become ubiquitous in advanced capitalist societies such that the creative imagination of the majority of both writers and architects had become almost completely urbanised. The city was no longer ‘a paradox, a monster, a hell or heaven that contrasted sharply with village or country life in a natural environment’ (Lefebvre 2003: 11). It had become the norm. As Raymond Williams commented, for many writers, ‘there seemed little reality in any other mode of life,’ such that ‘all sources of perception seemed to begin and end in the city, and if there was anything beyond it, it was also beyond life’ (Williams 1985: 230).

Nation, Empire and a Very Urban Revolution

The revolutionary process of capitalist urbanisation with all the social contradictions and psychological traumas that it engendered was no respecter of boundaries and sentiment. It was as unstoppable as it was invasive and would come to provide the contextual framework for all writers and architects, even those in remote garrets harbouring romantic dreams of autonomy from political diktat and economic servitude.4 Laughing at their delusions were characters like Peotr Petrovich who revelled in the demise of the old world. Holding court in a salon he declares in the spirit of Hegel that:

something definite has been accomplished; new and useful ideas have spread, new and useful writings disseminated in place of the old dreamy and romantic ones; literature has assumed a tinge of maturity; many harmful prejudices have been uprooted and held up to ridicule – In a word, we have irrevocably severed ourselves from the past and that, in my opinion, is something worthwhile, sir.

Dostoevsky 1989: 167

Petrovich’s self-conscious modernity was typical of the urban raconteur in the latter half of the nineteenth century who, caught in the slipstream of the European Enlightenment, and familiar with the ideas of thinkers like Descartes, Kant, Hegel and Adam Smith, was deeply conscious of the seismic consequences of the 1789 and 1848 revolutions and considered the construction of a new world view based on scientific reason and rational philosophical enquiry to be the epitome of what it meant to be modern.

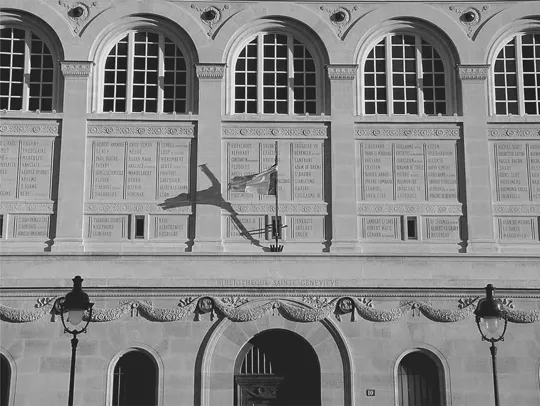

Figure 1.2 ‘Enlightenment, modernity and national identity’, Bibliothèque Ste.Geneviève, The Panthéon, Paris

There is no precise starting date for the advent of modernity. For some it is synonymous with the enlightenment and the political and cultural revolution of the early bourgeoisie. Alternatively we might argue that it begins whenever the first generation of liberated serfs clamber over the walls of the demesne, and migrate as ‘free’ wage labourers to the gaping pits and smoking chimneys that bored though the earth and clashed with church spires. In Dostoevsky’s Russia this was not to happen until the emancipation of the serfs in 1869, but it was a process that began in Britain much earlier, as migrant workers travelled to the sites of the industrial revolution, and to the sources of power, energy and raw materials, around which the first great modern industrial cities like Manchester and Glasgow were to develop. And it was in the midst of these new social and spatial formations that the epic battle between capitalist and worker commenced; new classed, gendered and racialised identities were formed; and a new vocabulary of social freedom and individual liberty was discovered.

Newly professionalised architects were confronted with a vast expansion in building typologies, new categories of clients, militant construction trade unions and revolutionary contracting procedures such as competitive tendering.5 Many devoted their lives to designing the institutions on which capital accumulation depended, magnificent stock exchanges dedicated to the circulation of money that rivalled the temples of antiquity; asylums, prisons and workhouses to classify and discipline mind and body; and staggeringly palatial neo-classical courthouses and seats of government to maintain law and order. Others however, motivated and appalled by the violent and transparent disparities in wealth and property, recast themselves as servants of the people and embraced the idea of an architecture of social commitment. What had begun in the architectural programmes of Utopian Socialists like Robert Owen and Charles Fourier, that had mutated into the architecture of philanthropic concern,6 was transformed again by the foundation of the first Local Authority Architect’s Departments that built networks of public libraries, schools, baths and housing at the turn of the twentieth century. It was a socialisation of architecture that culminated in the 1920s in the manifestos of politically motivated modernists across Europe who aspired to nothing less than the synthesis of a revolutionary social and technological programme.7

The modern novelist fills this new construction and architectural landscape with a glittering array of new rogues and heroes. Disgruntled aristocrats in their country houses, angry women imprisoned by antiquarian morals in rural towns, righteous suburban families semi-detached from the city, down-trodden workers in slums and ghettos, and lonely individuals lost in the urban crowd. These were just a few of an intricate cast of new characters that began to occupy the pages of a whole new literature of redemption, reconciliation, suffering and struggle. Literature might well attend to the trials and tribulations of the aristocracy and middle class, but it could also illuminate the ordeals of the poor and the insurgent in which location and architecture were everything. Through the modern novel the reader could now visit the grimy blackened towns and pits of Zola’s Germinal and Dickens’ Hard Times, encounter the People of the Abyss with Jack London, gaze with horror through the doors into the bloody meat factory of Upton Sinclair, express solidarity with the workers in Gorky’s factories, join the Wobblies in Dos Passos’ U.S.A. or empathise with the victims of Steinbeck’s dust bowl migrations. After what Lukacs had labelled the crisis of bourgeois realism, the historical novel appeared to have been reborn as a weapon in the class struggle, a literature that was ‘grand, dramatic, and rife with deep conflict in every phase’, and which aimed to present ‘the movement of popular life in history in its objective reality’.8

More broadly this socio-spatial narrative revolution was indicative of a new geographical imagination that was required to describe and map not only the transformation of relations between home and workplace, town and country, regions and nation state, but importantly between the nation state and an evolving integrated world system. Imagined or otherwise the marked development in forms of national consciousness and identity in the nineteenth century formed part of a more general cultural and ideological project that was reflected in the idea of a national architecture and literature. Fierce debates ensued on the character of the vernacular and on the meaning of national tradition and custom. Political symbolism to reinforce national identity became a powerful ideo...