![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

This book is concerned with children, families and schools. Its main themes centre on the nature of home school relationships and the impact of these on children’s development and learning. Within the context of the home school relationship, it seeks to highlight the importance of recognising the role of children as active participants in educational processes. Throughout, links are also made to the development of inclusive educational practice, and particular attention is given to issues relating to children with special educational needs. This chapter provides a brief introduction to the themes and their interrelationships.

Home-school relationships

It has long been recognised that the quality of home school relationships is associated with the educational outcomes that children achieve. In this country, official recognition of the significance of home school relationships dates as far back as the Plowden Report on primary education (DES, 1967), which described partnership between parents and teachers as ‘one of the essentials’ for promoting children’s educational achievements. Almost all government reports since then have endorsed the general principle that the closer and more positive the communication and collaboration between their teachers and parents, the better the outcomes for children.1 This principle is supported by the steady accumulation of research evidence that has built up over the years to demonstrate an association at an individual level between parental involvement and children’s academic attainments (e.g. Hewison and Tizard, 1980; Coleman, 1998), and at a whole school level, between parent teacher relationships, school effectiveness and school improvement (e.g. Ball, 1998; Wolfendale and Bastiani, 2000). More recently, positive home school relationships have also been linked to the promotion of inclusive educational practice (e.g. Gartner and Lipsky, 1999; Mittler, 2000).

Within educational policy, the terms ‘partnership with parents’ and ‘home school partnership’ have become well-established ways of referring to the ideal relationship that is aimed for. Although the terms are used in different ways and with differing emphases, there has been an increasing consensus that the notion of partnership must be underpinned by a recognition and valuing of the complementary roles that parents and teachers play in children’s education. This notion is not unproblematic, however, for despite the implicit principle of equality that it conveys, in practice parents rarely perceive that they have equal status to professionals in educational decision-making (Armstrong, 1995). Further, it is evident that the nature of home school relationships is affected by gender, ethnicity and social class variables (Vincent, 1996). Accordingly, while there is little doubt that children benefit when home school communication is characterised by reciprocity, trust and respect, it is important to acknowledge the diversity of relationships that exist between parents and teachers, and to recognise how distant these can be from the partnership ideal.

The quality of home school relationships is influenced by a large range of interacting factors. Within school, it is evident that teachers vary in the attitudes, knowledge, understanding, skills and commitment that they bring to their interactions with parents. Schools and Local Education Authorities (LEAs) also vary in both their policies and the degree of support they provide for this aspect of the teaching role. Similarly parents differ, for example in their confidence in dealing with the authority that schools represent, and in their familiarity with and expectations for their children’s formal education. Practical barriers to easy communication with schools can also arise, such as transport arrangements, or domestic and work commitments. Crucially, the home school relationship is also influenced by the child himself or herself. It is apparent, for example, that where parents see that their children are liked and valued by teachers, they are more likely to feel positive about communication and cooperation with school. At the same time, however, there is evidence that children seek to preserve some privacy in their home and school lives and to ‘manage the gap’ (Alldred et al., 2002) between them.

If schools are to develop their interaction with parents in line with partnership ideals, it is essential to acknowledge the complex nature of this three-way relationship between parent, teacher and child, and the ways in which this evolves over time as the child grows older. It is argued in this book, therefore, that partnerships between teachers and parents must also promote the role of children as active participants in their own education.

The active participation of children in educational processes

Research into children’s lives outside school (e.g. Brannen and O’Brien, 1996; James et al., 1999) has contributed to a recognition that children are not simply recipients of socialisation processes such as those initiated by their parents and teachers, but are active social agents in their own right, who both contribute to and hold their own distinct views on their experiences. With this shifting perception of childhood has come an increasing acknowledgement that child and parent or pupil and teacher perspectives do not necessarily coincide, and further, that children have the right to express their views and be listened to in matters that concern them.

By comparison with parent partnership, the principle of pupil participation in decision-making is not yet very well-established in educational policy. Nevertheless, within the school context, there is growing evidence that children do better personally, socially and academically when they are encouraged to take responsibility for their own learning (e.g. Cox, 2000; Weare, 2000; Bearne, 2002). Accordingly, greater attention is now being paid to ways of promoting their active involvement in educational processes. The notion of pupil participation, like the idea of parent partnership, is complex. It involves questions of power and responsibility as well as the need to accommodate diverse professional and community priorities and perspectives. It is apparent, for example, that principles of participation do not always fit comfortably with either a teacher’s professional stance or with a family’s cultural values. What is more, as a number of authors have begun to note (e.g. Brannen et al., 2000; Wyness, 2000), there is a potential tension between the principle of pupil participation and that of parent partnership. These writers observe that, if parents and teachers develop close communication and collaboration, then there is a risk that schools come to regard parents as always speaking for their children, rather than acknowledging that parents and children may hold differing perspectives. Where this is the case, the involvement of parents can serve to reduce the developing autonomy of their children in decisionmaking.

While these are real concerns, the risk must surely be reduced if both parents and teachers are alert to the need to listen to and take account of children’s views. What is required is an explicit attempt to develop the home school partnership in ways which support rather than constrain children’s active involvement. Indeed, there is scope for potential two-way support between parents and teachers when it comes to promoting children’s participation in decision-making both in and out of school (Beveridge, 2004). Parents typically have a wider range of experience of their children’s involvement in decision-making than teachers have. They frequently act as important mediators for their children, not only with schools but also more generally within the local community. This can be a particularly significant part of their role when their children have special educational needs (Dale, 1996; Read, 2000). However, the shift from advocacy on behalf of their children to a supporting role with respect to their child’s own self-advocacy is not necessarily an easy one for parents to put into effect, and it is evident that some parents would welcome explicit discussion with teachers and other parents about the issues involved.

Parents and teachers each have their own knowledge, understandings and experiences of children’s decision-making. Children are likely to require the support of both if they are to participate as fully as possible in educational processes. For these reasons, it is argued in this book that there is a need to explore the relationship between the principles of parent partnership and pupil participation and further, that through acknowledging the potential tensions between these two principles, it is more likely that both parental and child perspectives will be given due weight.

Inclusive education and special educational needs

The book’s central concerns with the development of parent partnership and pupil participation are located within the context of inclusive educational practice. The aim is to highlight both common issues and specific issues relating to children with special educational needs. Although the term ‘special educational needs’ is increasingly regarded as problematic by many writers, it remains current in both national and local policy frameworks, and for this reason is used throughout the book. According to the legal definition, children with special educational needs are regarded as those who ‘have a learning difficulty which calls for special educational provision to be made for them’ (Education Act, 1996, Section 312). Learning difficulty is further qualified by reference to significant difference from other children of the same age, or the presence of a disability which impedes access to educational facilities.

The conceptualisation of needs which underpins this rather circular definition is multifaceted. Debate continues about the processes involved and the relative importance of individual and environmental factors. However, there is a general consensus that the nature of the special educational needs that children experience arises in interaction between individual pupils and the demands which are made of them at school. It follows therefore that these needs are influenced by teacher pupil relationships and by curricular and organisational factors within school. Schools do not, of course, operate in a social vacuum, and an understanding of special educational needs must also be informed by recognition of wider-ranging influences beyond the school environment, including societal and political values and expectations. From this brief summary it can be seen that current interpretations of the notion of special educational needs carry some subtlety and complexity, which have accumulated over the years since the term was introduced. Nevertheless, it is important to be alert to the nature of the reservations which are now being increasingly expressed about its usage.

It is only too apparent that any label which is applied to a minority group can become stigmatising and devaluing, and carries the risk of placing undue and negative emphasis on difference from the majority. Specific criticisms of the ‘special educational needs’ label highlight the way that it directs attention onto the individual as ‘having’ particular needs, thereby locating the problem within the child, rather than focusing on the barriers to children’s learning that are implicated in the educational difficulties they experience (e.g. Hart, 1996; Booth, 1998).

While recognising the importance of the organisational, curricular and wider systemic barriers to learning that exist, however, there is no doubt that there are individual children who experience such difficulties in their learning at school that they require additional help if they are to make the most of their educational opportunities. Although some critics of the term ‘special educational needs’ would wish to abandon any label, others acknowledge that the use of a label can serve to identify those differences in children’s needs which are sufficiently significant to require the safeguarding of additional resource allocation in order to meet them. Nevertheless, critics question what benefit there is in separating special educational needs from other forms of exceptional need. They point out that a range of common principles can be described that underpin aspects of provision for children with special educational needs and for those learning English as a second language, those who are exceptionally able, those whose needs arise from disrupted schooling, and so on (e.g. Davie, 1996).

Growing concern about a lack of clarity in current interpretations of the term ‘special educational needs’ is also reflected in Norwich’s (1996) proposal of a unifying framework for considering the overlaps and boundaries between the full range of educational needs that children experience. Within this he distinguishes between common learning needs, which are shared with all of a child’s peers; individual needs, which reflect the range of individual diversity found among all children; and exceptional needs, which arise from special characteristics or circumstances and which may be shared with a subgroup of peers. The exceptional needs he identifies include aspects of children’s learning and emotional and behavioural difficulties, but also go well beyond current governmental policy definitions of special educational need.

The term ‘exceptional needs’ has been adopted by a number of writers, such as Mittler (2000), who finds the continuing use of the special educational needs label ‘not only anachronistic but discriminatory’ (p. 8). In his view, it serves to create a perception of a need for separate provision that is quite at odds with current policy initiatives to promote greater inclusiveness within education. This argument provides a useful reminder that concepts such as special educational needs and exceptionality are socially constructed, and cannot be viewed in isolation from the political and policy contexts in which they arise. It is therefore to be expected that not only our understandings of, but also our ways of referring to, significant aspects of individual difference will shift over time. However, although the government has acknowledged some of the problematic issues associated with present definitions and interpretations of special educational need (DfEE, 1998), it has nevertheless chosen to retain these in current legislation and guidance. Accordingly its policy has been one of clarification rather than re-formulation of terms, for example by distinguishing the boundaries and overlaps between the terms ‘disability’ and ‘special educational need’ (DfES, 2001a), and by proposing a framework for classifying different types of special educational need (DfES, 2003a).

The way in which we refer to children’s needs carries subtle messages about what sort of provision we see as most appropriate for meeting those needs, and Mittler is not alone in linking his concerns about terminology to the question of inclusive education. Like others, he describes inclusive educational practice as necessitating ‘a process of reform and restructuring of the school as a whole, with the aim of ensuring that all pupils can have access to the whole range of educational and social opportunities offered’ (Mittler, 2000: 2). In other words, the essence of inclusive education can be characterised as a flexible and responsive school system which, as Wedell (1995) has argued, takes as its starting point a recognition of the diversity of pupils’ needs. This perspective highlights two significant and complementary implications for the development of practice: first, that any attempt to implement inclusive education must embrace the needs of all pupils; but second, that for some of them, there is a risk of exclusion or marginalisation to be redressed.

This book attempts to engage with both these implications. Adopting Norwich’s (1996) framework, it aims to address questions concerning principles and practices in the development of home school relationships and pupil participation that are common across all children; it reflects upon the significance of individual diversity; and it gives explicit consideration to those exceptional issues that are distinctive to children with special educational needs.

Interrelationships

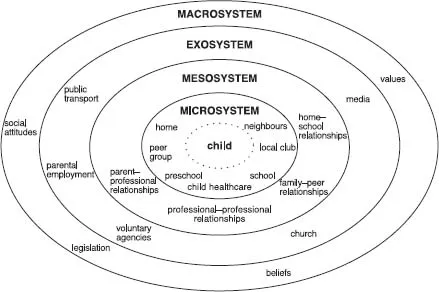

The ways in which the themes of the book interrelate with each other is best illustrated by reference to the ecological model of development proposed by Bronfenbrenner (1977). This model provides a convincing theoretical rationale for why home, school and the relationship between them are so significant for children’s development. It also emphasises how important it is that the child be recognised as an active participant in both home and school contexts.

Bronfenbrenner describes an ecological framework for development that can be characterised as a nested system of environments. These environments are differentiated into four levels as outlined in Figure 1.1. At the innermost level is what he refers to as the microsystem, which is made up of the complex system of relationships that a developing child has with the immediate environments in which he or she is living and learning. Bronfenbrenner is explicit that home is the primary learning context for most children within the microsystem, but further significant settings are likely to include preschool and school contexts, neighbourhood friends and peer groups and other local community contexts. For children with special educational needs, they may also include child health centres, speech and language therapy clinics and so on. Within each setting, Bronfenbrenner stresses that developing children are not passive recipients of their environmental experiences, but that they both influence and are influenced by their interactions in a process of ‘progressive, mutual accommodation’ (1977: 514). Accordingly, different children will experience the same environmental contexts differently because of their own active contribution to the interactions that take place.

Figure 1.1 Bronfenbrenner’s ecological framework (based on Bronfenbrenner, 1977, 1979)

The second level is referred to by Bronfenbrenner as the meso-system. This system does not comprise discrete environmental settings, ...